Transcription

MusicEducation:State ofthe NationReport by the All-Party Parliamentary Groupfor Music Education, the Incorporated Societyof Musicians and the University of SussexAll Party Parliamentary Group logo - high res.pdf122/01/201909:45

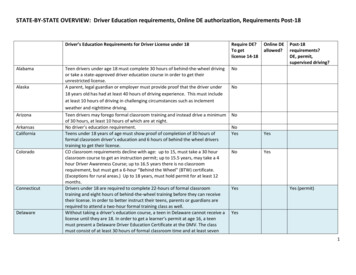

ContentsForeword2Executive Summary3The importance of music educationWhat is education? What does music contribute to our economy?Music’s contribution to cultural life Music’s contribution to social and individual wellbeing What can music education contribute?444445Music education in England Music education initiatives Music Manifesto Henley Review The National Plan for Music Education Music Education Hubs666788The core and extension roles of Music Education Hubs9Music education in schools Primary schools Secondary schools Secondary school accountability measures (the EBacc) What happens at GCSE? Uptake at Key Stage 5 The negative impact of the Russell Group list of ‘Facilitating Subjects’ Wider implications of current accountability measures1010101214151616Impact on the broader music education landscapeGraded music examinationsRecommendations181919Music Education Hubs and the National Plan for Music EducationRecommendations2021The role of OfstedRecommendations2224The workforce The workforce in secondary schools The workforce in primary schools The workforce in music education ions summary2929About About the authors About the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Music Education About the Incorporated Society of Musicians (ISM) About the University of Sussex3232333333References34

ForewordThere is increasing cross-party concern about thecrisis facing music education in England in particular.Over the past decade there have been manypositive developments, perhaps most notably the2012 National Plan for Music Education. However,the overall picture is one of serious decline. If thepace continues, music education in England willbe restricted to a privileged few within a decade,and the UK will have lost a major part of the talentpipeline to its world-renowned music industry.The All-Party Parliamentary Group for MusicEducation was set up to bring together MPs andpeers from all parties who believe in and supportmusic education for our children. This report,published in collaboration with the University ofSussex and the Incorporated Society of Musicians,shows the scale of the crisis facing music educationin England. It shows how Government policy aroundaccountability measures and the curriculum hascontributed to a sharp decline in opportunitiesfor pupils to have access to a music education. Itsrecommendations show the breadth of the problem– but also how easily the Government could act toaddress some of the most pressing issues, at little orno financial cost.2Music Education: State of the NationWe hope the Government listens to the concernsfrom both sides of the House and acts on therecommendations in this report, whose authors areDr Alison Daubney (University of Sussex), Gary Spruce(Birmingham City University) and Deborah Annetts(Incorporated Society of Musicians).Diana Johnson MP (Labour),Co-Chair and Registered ContactAndrew Percy MP (Conservative),Co-ChairJanuary 2019

Executive SummaryAll children should have access to a high-qualitymusic education.Studying music builds cultural knowledge and creativeskills. It improves children’s health, wellbeing andwider educational attainment. The creative industries,now worth more than 100 billion to the UK economy,rely heavily on the pipeline of creative talent fromschools which has been essential in creating theUK’s world-renowned music industry. Music alsoenables young children to develop the sheer love ofexpressing themselves through music, discoveringtheir own inner self and being able to developemotional intelligence and empathy through music.Music education: in crisis?Government policy, particularly around accountabilitymeasures like the English Baccalaureate (EBacc), hassignificantly negatively impacted on music educationin schools in England. Curriculum time for music(which is statutory for Key Stage 1–3) has reduced,along with opportunities for children to pursue musicto GCSE and A Level.The Department for Education’s own data showsa fall of over 20% in GCSE music entries since2014/2015 – a 17% fall when adjusted for reducedcohort size. Secondary school music teacher numbershave fallen by over 1,000 in the same period ata time when EBacc subjects are seeing teachernumbers rising. The decline in GCSE music is awarning for other non-EBacc subjects, with manyother non-EBacc subjects suffering similaror worse outcomes.What can be done to reversethe decline?To address the decline in music education theGovernment should ensure that all schools shouldteach music on a regular and sustained basis acrossthe whole of Key Stages 1-3 irrespective of whetherthey are an academy or not. The Government shouldalso review and reform the EBacc and Progress 8, tomake sure that our children are getting the educationthey need for the 21st century, not one which isrooted in the 1904 Secondary Regulations. And at itsheart must be creative education.The EBacc must be addressedResearch set out in this report highlights the seriousfailings of the EBacc policy which urgently need tobe addressed.To date the target of 75% (90% by 2025) for EBacctake up has failed to be met by a very long way.Currently the number of students studying the EBacchas plateaued at around 38% in state-funded schools.Indeed the number of students passing the EBaccwas just 16.7% in 2017/2018. And yet this failingpolicy is causing untold damage to music and manyother creative subjects in our schools. And for what?Workforce under pressureThere are serious questions to be addressedregarding the music education workforce that isdemoralised from the marginalisation of music inour schools, as well as facing both skills and fundingshortages. As the Government has recognisedpreviously 1, children must be taught by subjectspecialists 2, with schools supported by appropriateexpertise and overseen by appropriately trainedinspectors. The revised National Plan for MusicEducation (NPME) must also provide clarity overthe roles and responsibilities of schools and MusicEducation Hubs (“Hubs”), and find more effectiveways of measuring Hubs’ success.When schools teach creative subjects, the wholeof our society and economy benefits. The musicindustry in Britain is worth 4.4bn a year to theeconomy. It punches above its weight internationally.Britain has less than 1% of the world population, butone in seven albums sold worldwide in 2014 wasby a British act. This is a critical part of Britain’s softpower. In the current Brexit landscape this becomeseven more vital.Music Education: State of the Nation3

The importance of music educationWhat is education?Music’s contribution to cultural lifeWe define education as the means by whichindividuals and groups come to a better understandingof the world. As the music educationalist John Paynterwrote, ‘The value of anything we learn in school lies inthe extent to which it helps us to respond to the worldaround us’ 3.From symphony orchestras to brass bands, rock groupsto chamber music ensembles and cathedral choirs tospectacular musical theatre, music making in the UKis defined by its excellence and diversity. Each musicaltradition has its own distinctive practices and measuresof quality and each makes a unique contribution to thenation’s culture. For UNESCO, ‘Culture is the fountainof our progress and creativity and must be carefullynurtured to grow and develop‘ 7.What does music contribute toour economy?Music has a significant impact on the UK’s economy.UK Music’s ‘Measuring Music’ reports the followingheadline figures for the contribution of music to theUK economy in 2017 4 :···· 4.5 billion gross value (GVA) contribution to theeconomy 2.6 billion total export revenue5145,81 full time equivalent jobs are within the musicindustry (an increase of 3% from 2016)12% increase in overseasThe Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport(DCMS) Sector Economic Estimates showed the valueof the creative industries rose by 7.1% in 2017 (from 94.8 billion in 2016 to 101.5 billion in 2017), almostdouble the 4.8% increase across the UK economyas a whole. As the UK Creative Industries Council(CiC) points out, this means that ‘the UK’s creativeindustries contributed more than 278 million aday, or approximately 11.5 million in every hourof 2017’6. CiC also notes how from 2010-2017 ‘thecreative industries subsectors’ (which includes music)grew by 53.1%This is the fastest growth rate of any ofthe categories overseen by the Departmentof Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, which hasresponsibility for areas including tourism,telecoms, gambling and charities, and makesthe creative industries among the bestperforming of any industrial sectors 6.4Music Education: State of the NationDeep in our hearts, we all understand that thequality of our lives depends, to a great extent,on our being able to take part in, and benefitfrom our culture. We instinctively know, withno need for explanation, that maintaining aconnection with the unique character of ourhistoric and natural environment, with thelanguage, the music, the arts and the literature,which accompanied us throughout our life, isfundamental for our spiritual wellbeing and forproviding a sense of who we are. There is anintrinsic value of culture to a society UNESCO 8Music’s contribution to social andindividual wellbeingSignificant research has demonstrated the positiveimpact of participation in the arts on wellbeingand physical and mental health9 10 and also on howparticipation in music, coupled with a coherentand sustained music education, can deliverpositive benefits to wider cognitive development(e.g. improved literacy and numeracy skills11).Music plays a role in the individual lives ofeveryone, the way individual and collectiveidentities are expressed and given meaning12,and marks special occasions.The index of wellbeing compiled by Age UK marksthe leading factors in being happy as ‘cultural

participation, physical activities, cognition, mentalwellbeing, education, no diagnosed healthconditions, an open personality, no limiting longstanding illnesses, and social participation.’ 13What can music educationcontribute? Subjects like design and technology, music,art and drama are vitally important for childrento develop imagination and resourcefulness,resilience, problem-solving, team-working andtechnical skills. These are the skills which willenable young people to navigate the changingworkplace of the future and stay ahead of therobots, not exam grades. These meta-skillsare critical in all sectors, not just the creativeindustries.14Tristram Hunt, Director of V&A (2018)Music education in its many forms and settingsprovides the foundation for the diversity andexcellence that characterises music making in the UKand ensures there is a ‘talent pipeline’ 15 that sustainsthe economic benefits as outlined above.Professor Gert Biesta, Professor of Education atBrunel University, states that a good educationperforms three core functions16 :1. To produce a suitably qualified workforce(Qualification) which can support the economicwellbeing of the nation;To induct children and young people into the2. values and norms of society including its culturesand traditions (Socialisation)3. To support children and young people to becomeautonomous, creative and individual thinkers andactors (Subjectification).A strong music education contributes to all of thesethree functions. Qualification ensures that thereis a steady supply of performers, composers andarrangers that have the necessary musical skills foremployment in the creative sector. Socialisationensures that children and young people know about,and engage with, music in society. The third function,Subjectification is considered to be the most valuablecontribution made by music education.Biesta states the present emphasis on accountabilityand measurement in education has restricted thesubjectification function, which is vital in meeting thechallenges of the future including preparing youngpeople for employment. The issues of employabilityhighlighted by Hunt and Biesta are reinforcedthrough research undertaken by NESTA and theCreative Industries Federation: future economy will be built on creativityOurand technology. With artificial intelligencetaking over routine tasks, there will be immenseopportunities for people who combine creative,technical and social skills – skills that are resilientto future automation.17A recent report18 by Carl Frey, co-director of theOxford Martin programme on technology andemployment at Oxford University, suggests that15 million jobs are at risk of automation in theUK. Artists, including musicians, are at low risk ofautomation (1.49% chance), alongside doctors,surgeons, audiologists, prosthetics makersand occupational therapists. In 2018 the CBIPresident Paul Drechsler called on policymakers toprioritise teaching that encourages creativity andteamworking19.Therefore in the age of increasing automation weneed an education system which has at its heartsubjects like music which expands minds andbuilds problem solving skills and creativity. Theindustry is clear what it needs – but unfortunatelycurrent education policy runs counter to the needsof business.Music Education: State of the Nation5

Music education in EnglandMusic has long been considered a part of a broadand balanced school curriculum20. It has been part ofthe statutory school curriculum until the end of KeyStage 3 (age 14) since the National Curriculum waspublished in 1988/9. The entitlement to school musiceducation was recently reaffirmed by the SchoolsMinister, Nick Gibb: high-quality arts education should not bethe preserve of the elite, but the entitlement ofevery child. Music, art and design, drama anddance are included in the national curriculum andcompulsory in all maintained schools from theage of 5 to 14 21.Nick Gibb, April 2018The National Curriculum Programme of Study forMusic22 (“the National Curriculum for Music”) haspractical music making and diversity and inclusion atits heart. Children and young people’s understandingof music is about developing their knowledge ofmusic and skills in music making through the coremusical activities of making music (as performers,composers/producers and improvisers) andresponding critically and in an informed way tomusic from a wide range of genres and traditions.It has been long-recognised, however, that whereascurriculum music in school should form the foundationof children and young people’s music education, itis not enough on its own. Most schools, as a result,provide a range of extra-curricular opportunities foryoung people to develop their musical interest, suchas school orchestras, choirs and other ensembles.Music education initiativesOver the last 18 years, however, there has been aproliferation of music education initiatives instigatedand funded both by the Government and also by nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and charitableand commercial bodies. These often have as theirprimary purpose increasing access to and diversity in6Music Education: State of the Nationmusic education. Government initiatives include thefunding of Whole Class Ensemble Teaching (WCET)/First Access programmes which seek to ensure thatall primary children receive tuition on an instrumentfor at least one term and ideally a year. AnotherGovernment supported initiative, Sing Up, led byThe Sage, Gateshead received 10 million pounds in2007 to revitalise singing in schools, reaching over90% of schools. The Voices Foundation continues todevelop “singing schools” in schools with high levelsof deprivation, particularly in the primary sector withsinging being integrated into all kinds of classroomactivity. Musical Futures, supported initially by thePaul Hamlyn Foundation, continues to address issuesof diversity, access and inclusion in music educationthrough introducing informal learning approaches intothe music classroom in order to address the alienationof some young people from formal music educationand increasing the take-up of music at GCSE.Organisations and charities such as Youth Music23,Music for Youth24 and In Harmony25 and alsoeducational outreach projects by orchestras andopera companies address particular aspects of musiceducation and do immensely valuable work in workingwith disadvantaged groups of children and youngpeople and/or those whose music needs are not metby the more established music education structures. Inaddition, there is the directly funded Music and DanceScheme26, which provides grants for specialist trainingfor young dancers and musicians with exceptionaltalent to enable them to attend specialist independentschools or centres for advanced training.Although the provision is welcomed, it has raisedconcerns that music education is fragmented asa result. In 2010, Ed Vaizey expressed a concernthat ‘we are losing sight of the key aims of culturaleducation in a blizzard of initiatives’27.Music ManifestoThe Music Manifesto28, launched by the Departmentfor Education and Skills and Department for CultureMedia and Sport in 2004, attempted to address the

patchiness and postcode lottery nature of provision.This was a joint campaign between the Departmentfor Education and the Department for Culture, Mediaand Sport (now Digital, Culture, Media and Sport). Itsaim was to improve young people’s music educationin England, promoting a ‘music for all’ agenda.The purpose of the Music Manifesto was to:····act as a statement of common intent that helpedalign currently disparate activity set out a sharedagenda for planning across the sectormake it easier for more organisations andindividuals to devise ways to contribute to musiceducationguide the Government’s own commitment tomusic educationcall on the wider community, including the public,private and community sectors, to joinin enriching the lives of schoolchildren.The campaign’s Five Key Aims were to:·····The parameters of the review, set out by the thenSecretary of State for Education, Michael Gove, onceagain highlighted that ‘the Government prioritiesrecognised music as an enriching and valuablesubject ’30 and also reaffirmed the commitmentthat ‘public funding should be used primarily tomeet the Government priorities of every childhaving the opportunity to learn a musical instrumentand to sing.’ The Government also recognised the‘secondary benefits of a quality music educationare those of increased self-esteem and aspirations;improved behaviour and social skills; and improvedacademic attainment in areas such as numeracy,literacy and language.’The Henley Review set out recommendations forthe minimum expectations of what any child goingthrough the English school system should receive interms of an education in music. It highlighted highquality and sustained music education in the schoolcurriculum as the cornerstone of every child’s musiceducation, hailing the importance of music in thecurriculum in the first recommendation:provide every young person with first accessto a range of music experiencesprovide more opportunities for young peopleto deepen and broaden their musical interestsand skillsidentify and nurture the most talented youngmusiciansdevelop a world-class workforce in musiceducationimprove the support structures for youngpeople’s music making.Henley ReviewThe report Music Education in England 29, otherwiseknown as the ‘Henley Review’, was published in2011. Darren Henley, the then-Managing Director ofClassic FM (and now Chief Executive of Arts CouncilEngland) undertook the review. ‘Schoolsshould provide children with a broadMusic Education, which includes performing,composing, listening, reviewing and evaluating.’It also highlighted challenges and threats to musiceducation, including:·····inappropriate accountability measures (EBacc)which worked against the Artsinsecurity of fundingpatchy provision that led to inequality of accessa lack of accountability for the quality of workdelivered by Music Services and music educationwork funded by Arts Council England andYouth Musicissues regarding training, recruiting andsupporting the diverse workforce.Music Education: State of the Nation7

A particularly prescient observation was made in theReview at 4.2‘There is a strong sense that the statutoryrequirement of being included in the NationalCurriculum provides a basis for all other musicprovision in and out of school. Without theobligation for music lessons to be a part of theschool curriculum, there is a very real concernthat the subject might well wither away in manyschools – and in the worst case scenario, could allbut disappear in others.’The National Plan for Music EducationThe NPME 31 was born out of the review and is basedon its recommendations. The NPME is an ambitious,aspirational document which sets out clear objectiveswith regards to delivery, access, progression andexcellence in the music education sector. The NPMEwas launched in 2012 and continues to 2020.The NPME’s main aim was to ensure that access tomusic education was not impacted by a postcodelottery. The vision was to ensure that opportunitieswere equal and available. Notably, the NPMErecognised the first opportunity that many pupils willhave to study music will be at school and that thisfoundation should be nurtured to provide broaderopportunities and progression routes.Music Education HubsThe NPME introduced the concept of Music EducationHubs (“Hubs”), which built on the work of localauthority music services. The Hubs comprise groupsof organisations – such as local authority musicservices, schools, other Hubs, Arts organisations,community or voluntary organisations. The Hubswere designed to augment and support musicteaching in schools (a guaranteed statutoryrequirement to the end of Key Stage 3) so thatmore children could experience a combination ofclassroom teaching, instrumental and vocal tuitionand input from professional musicians, as set out by8Music Education: State of the Nationthe NPME. The structure of the various organisationsalso meant that Hubs would be able to deliver amusic offer that drew on a wide range of expertise.The NPME stated that the Hubs in ‘every area willhelp drive the quality of service locally, with scopefor improved partnership working, better value formoney, local innovation and greater accountability’.The Hubs were also promoted as having an importantrole in ‘first access’ to music through continuing todevelop the whole-class instrumental and vocalprogramme for a minimum of a term in primaryschools, as well as providing broader opportunitiesand progression routes inside and outside theclassroom. The idea was that class teachers andspecialist instrumental teachers working togethercould maximise opportunities for musical progressionand provide for different needs and aspirations ofpupils beyond the music curriculum.The NPME also promoted the benefits of music tothe wider life of the school, stating that schoolsshould have a choir and aspire to having an orchestraor other large-scale ensemble. The focus on singingbuilt upon the very successful work of Sing Up, theNational Singing Programme. This was funded by theGovernment between 2007 and 2012 and reached98% of primary schools at its peak32.The NPME asked the Hubs to develop singingstrategies, in and beyond schools, to ensurethat every child sings regularly and that choirsare available for them to join – with the viewof widening singing opportunities for all pupils,improve quality and give routes for progression suchas county choirs, chorister programmes and theNational Youth Choir.Although promoting partnership working andlocal innovation, the NPME set out core roles andextended roles for the Hubs to ensure nationalconsistency and equality of opportunity.

The core and extension rolesof Music Education HubsCORE ROLESEXTENSION ROLESa) Ensure that every child aged5-18 has the opportunity to learna musical instrument (otherthan voice) through whole-classensemble teaching programmesfor ideally a year (but for aminimum of a term) of weeklytuition on the same instrument.a) Offer CPD to school staff,particularly in supporting schools todeliver music in the curriculum.b) Provide opportunities to play inensembles and to perform from anearly stage.c) Ensure that clear progression routesare available and affordable to allyoung people.b) Provide an instrument loan service,with discounts or free provision forthose on low incomes.c) Provide access to large scaleand / or high-quality musicexperiences for pupils, workingwith professional musicians and/ or venues. This may includeundertaking work to publicise theopportunities available to schools,parents/carers and students.d) Develop a singing strategy toensure that every pupil singsregularly and that choirs and othervocal ensembles are available inthe area.Music Education: State of the Nation9

Music education in schoolsWhilst the aspiration is for every child aged 5 to 14to have regular access to music education throughthe school curriculum, evidence shows that thereality is somewhat different. A squeeze on fundingand pressure on the curriculum due to accountabilitymeasures is the cause of this. These are the samechallenges as noted by Darren Henley in the HenleyReview, but they have become so serious that theynow challenge the very existence of music education.Additionally, the changes in school structures mean thatthe National Curriculum is not statutory in academies.They are not required to follow the national curriculum.The National Audit Office reported that in January 201872% of secondary schools and 27% of primary schoolswere academies or free schools33 and thus not obligedto follow the national curriculum.‘Some schools perceive [that] they havepermission to either ignore the curriculum orjustify one-off end of year shows or projects asacceptable forms of music provision. Only weeklyprogressive music lessons can develop pupilseffectively in musicianship skills.’I nclusion manager (Consultation on the Futureof Music Education, ISM, December 2018 37)Primary schoolsIn recent research by the ISM, the pressure ofaccountability measures for maths and Englishresults (especially in Year 6) was noted to have anegative impact on curriculum music provision inprimary schools, and in primary schools where musicwas part of the curriculum, more than 50% of theresponding schools did not meet their curriculumobligations to Year 6, citing the pressure of statutorytests as a significant reason for this.34 This issupported by observations from Ofsted.Other research has cited the ‘lottery’ nature ofmusic education: primary school children’s accessto a sustained and high-quality music educationare governed by chance.35 36 37 This is a result of acombination of lack of teacher confidence, cuts10Music Education: State of the Nationto funding which have forced some schools to nolonger employ specialist music teachers and anunequal focus on core subjects, at the expense ofthe wider curriculum. saw curriculum narrowing, especially in upperWekey stage 2, with lessons disproportionatelyfocused on English and mathematics. Sometimes,this manifested as intensive, even obsessive, testpreparation for key stage 2 SATs that in somecases started at Christmas in Year 6.Amanda Spielman, Chief HMI, Ofsted39Opportunities to sing are also diminishing. Theprevalence of singing in primary schools has alsodiminished since the central funding for the NationalSinging Programme Sing Up was cut. At its peak SingUp39 was used in 98% of state-funded primary schoolsin the UK and contributed significantly to teacherdevelopment as well as helping schools and studentsreap the benefits gained from regular singing40.Secondary schoolsSignificant research into secondary school musicprovision has highlighted the decline of music as acurriculum subject right across secondary and post-18(tertiary) provision41 42 43 44.··Statutory provision is often curtailed: musicis no longer taught across Key Stage 3 in morethan 50% of state-funded secondary schools,including some schools still under local authoritycontrol where it is supposed to be a statutoryrequirement until the end of Year 945.I n some schools there is no music provisionor it is only taught on one day per year: recentfindings from the University of Sussex highlightthe marginalisation of music in the curriculum,highlighting that some pupils have little or nomusic education during their entire secondaryschool career; it therefore becomes the preserveonly of those that can afford to access it outsideof the classroom.

··T here is a lack of continuity: in Key Stage 3,there is an increasing move towards music onlybeing offered on a ‘carousel’, i.e. where music isonly offered for part of the year on rotation withother (usually arts) subjects.T he time allocated to music in the Key Stage3 curriculum is reducing: curriculum timehas been taken from music and given to EBaccsubjects45. This reduction in the percentage oftime allocated to music is highlighted by analysisof the figures in the DfE workforce survey,which clearly show that the percentage of timeallocated to music in Key Stages 3 fell by 6.34%between 2010 and 2017; only 3.1%46 of curriculumtime is now allocated to Key Stage 3 music.‘ Music has taken a battering in schools. By reducingits importance, SMT are less likely to pay for CPDopportunities and career progression opportunitieswill be favoured for EBacc subject leads. If musicteachers are not valued, schools working onperformance-related pay will not reward musicdepartments. [There’s] reduced timetabling forstudents to develop music skills, however there’sstill the same expectations of school concerts etc.’S econdary school music teacher (Consultation onthe Future of Music Education, ISM, December 2018 37)YearThese factors work directly against t

significantly negatively impacted on music education in schools in England. Curriculum time for music (which is statutory for Key Stage 1–3) has reduced, along with opportunities for children to pursue music to GCSE and A Level. The Department for Education’s own