Transcription

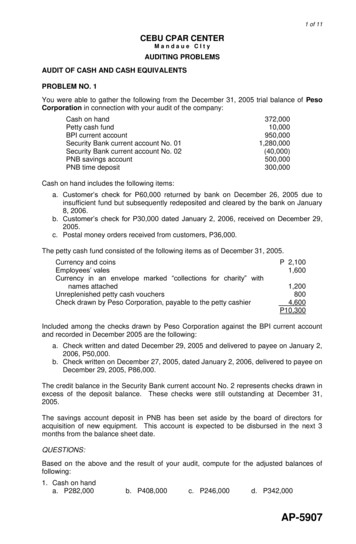

ARIZONA COOP E R AT I V EE TENSIONProblems and Pests of Agave,Aloe, Cactus and YuccaAZ 1399Revised 03/11

Table of ContentsAbiotic (non-living) problems.3Selecting the correct plant and planting location.3Freeze Damage.3Sunburn.3Planting depth.4Poorly–drained soils.4Irrigation.4Hail damage.4Diseases.4Fungal diseases of pads and leaves.4Phyllosticta pad spot .4Anthracnose of agaves .5Other fungal lesions .5Fungal crown rot of Echinocereus .5Pythium rot of barrel cacti.5Root and crown rot of agaves.6Bacterial necrosis of saguaro.6Sammon’s virus of Opuntia.6Insects.6Agave Snout Weevil (Scyphophorus acupunctatus).7Cactus longhorn beetle (Moneilema gigas).7Cochineal scale (Dactylopius coccus).7Plant bugs.7Coccid scale, soft scale .8Mites.8Animals.8For More Information.92The University of Arizona Cooperative Extension

Agaves, aloes, cacti and yuccas are classified as succulents plants that have highly specialized anatomical features such asthick waxy cuticles, fleshy or minimal leaves, modified leaves(spines), and roots with extra storage capabilities for food andwater. These modifications allow them to survive and thrivein harsh desert environments. They survive long periods ofdrought in areas of sparse rainfall and intense heat. Duringstressful periods many succulents cease to grow. They dropunnecessary leaves, dehydrate and become dormant untilconditions for growth return.Despite their adaptations succulents suffer from diseases,insect pests and cultural problems. Some of the more commonproblems that occur in agave, aloes, cacti and yuccas in Arizona are discussed in this bulletin.Abiotic (non-living) problemsAbiotic problems are not caused by living organisms. Theyinclude poorly drained soils, sun exposure, and weatherevents such as cold and high temperatures, excessive rainfall,over watering, planting too deeply and hail damage. In transplanted agaves, aloes, cacti and yuccas, abiotic problems areprobably the most common problems that growers and homeowners encounter.Selecting the correct plant and planting locationCareful selection of species that are suited to your local conditions is necessary and will eliminate or diminish seriousproblems. Choose species that are found in your neighborhood or area. Visit specialty cactus and succulent nurseriesand discuss cold hardiness, heat and cold tolerance, maturesize of the plant, growth rate and known problems of a specificplant with the nursery personnel. Contact your local Cooperative Extension office for expert advice. Visit local arboreta thathave extensive succulent collections. Choosing the right plantfor the right place is the first step in successfully growing theseunique plants.Most succulent species originate in areas of diverse habitats.For example, many agaves grow in pine and oak forests, opengrasslands and even in barren open areas. By researching alittle about your plants and their special requirements, theycan be planted in areas of your yard that fulfill most of theirrequirements.Freeze DamageFigure 1. Freeze damage on Agave.Many of the more showy andexotic succulents originated infrost-free climates. As a result,when temperatures remain below freezing for several hours,they suffer freeze damage. Thedamage originally manifests itself as blackening of the exposedparts of the plant (Fig. 1). Aftera few weeks, the blackened areawill dry out and become crisp.Freeze damage cannot be re-paired; but unless the freezeis of particularly long duration or exceptionably cold, thedamage may be only cosmetic,and the plant will grow out ofit. When exposed to a severefreeze, portions of columnarcacti will yellow, and then diecompletely (Fig. 2). In freezedamaged barrel-type cactus,the margins of ribs becomestraw yellow. If temperaturesFig. 2. Severe freeze damage to Cereusare not substantially belowperuvianus.freezing (a “hard freeze”) andthe freeze lasts for only a few hours or less, only the epidermis may be damaged, and the plant will outgrow the damage in several years. Yuccas may be damaged by sub-freezingtemperatures. The damage will appear similar to that of thefreeze damaged agave in Fig. 1. When the freeze is of longduration, extreme, or the species is not suited for the local climate, damage may be severe.Freeze damage can be prevented. It is important to becomeacquainted with temperature requirements of the particular species. Protective measures often can be taken to assuresurvival. Cold-sensitive plants should be grown in areas thatreceive radiated heat at night from a patio or wall or in hillyareas where air temperatures are slightly warmer.Covering the plant with a cotton sheet will help on nightsthat are just at or slightly below freezing. Another strategyis to place a 60-watt light bulb under the cotton sheet, takingcare that the light bulb does not touch the plant or the cottonsheet. Do not cover the plant with plastic sheeting. Plasticis a poor insulator and will transfer the cold directly to theplant wherever it touches the plant. Containerized plants canbe moved indoors until freezing weather has passed. If keptdry and placed in a brightly lighted area, they will survivewithout damage.Extremely low temperatures may cause a loss of turgor insaguaros. This causes sagging of branches (arms) or deathof the apical meristem (growing tip) that results in saguaroswith many stems or ‘heads’.SunburnSunburn is a commonproblem in greenhouse orshade house grown plants. Itis also problematic in plantsgrown in open beds or filtered sunlight in nurserieswhen these plants are transplanted into open landscapes.Those parts of the plant thathave not been acclimated toFigure 3. Sunburn on golden barrel cactus. direct sun will burn easily.Sunburned plants turn yellow. As the damage progresses, the epidermis turns strawyellow and dies. Barrel cacti and columnar cacti are veryThe University of Arizona Cooperative Extension3

susceptible to this kind of damage (Fig. 3). The entire plantusually does not die, but it is permanently scarred. Similardamage occurs on Y. aloifolia, Y. gloriosa, and Y. recurvifolia, especially during summer months. The apex of the leaf or thearea where the leaf naturally curves will become yellow. Insevere cases leaves may die, but if damage is not severe, theymay recover at cooler temperatures.Sunburn can be minimized in nursery-grown plants byplacing the plant in the same direction as it had been previously growing. Many nurseries will mark one side of theplant so it can be transplanted in the same orientation. Placingshade cloth (30%) or cheese cloth over newly-acquired plantsreduces sunburn. If possible, purchase locally grown plantsthat have been grown in full sun or partial sun (depending onthe species) and acclimated to sunlight.Greenhouse-grown plants that will be planted in the opengarden can be acclimated by gradually moving them out intofull sun over a period of weeks or planting in shade of a deciduous tree or shrub. Planting in late winter when solar radiation is less intense and using inorganic mulch such as gravelor decomposed granite around new plants also will reducesunburn. Application of a mulch about two to four inches (5 10 cm) deep will help retain soil moisture and reduce reflectedlight and heat, but be sure the mulch does not cover the baseof the plant and create a moist environment for rot organisms.Many species will benefit from partial or dappled shade. Byplanting near a deciduous tree or shrub, the plant will be protected from the summer sun and winter freezes.Planting depthProper planting depth is essential for the survival of manysucculents. In columnar cacti such as saguaro, green stemtissue should not be below ground. This is commonly donewith Carnegiea gigantea (saguaro) and other columnar cacti andleads to poor establishment and death of the plant. Do not attempt to ‘match’ plant sizes so that all the plants are identicalin height by planting some deeper than others. Young pricklypear (Opuntia spp.) should be planted deeply enough so thatthey remain upright after planting. This usually is ½ to ¾ ofthe depth of the lowest pad.Poorly-drained soilsAll succulents require fast-draining soils. Special ‘cactus’mixes are available at many retail nurseries. These mixes areformulated for potted plants. Poorly-drained soils will predispose the plants to attack by soil-borne, root-rotting pathogensthat may result in the death of the plant. Careful irrigationmanagement is critical in growing cactus, agave, and yuccasuccessfully in heavy clay soils. In outdoor landscapes, adding copious amounts (up to 25%) of pumice will improvedrainage and soil structure.Sandy soils should be avoided because they will drain veryrapidly and retain little water and nutrients. They should beamended with well-rotted compost or peat moss. Fresh or uncomposted manures should not be used as soil amendmentsbecause the high salt content found in manures is detrimentalto root development.4The University of Arizona Cooperative ExtensionIrrigationOne of the most serious abiotic problems is over-watering. This combined with poorly drained soils is a recipe forplant failure. Plants should dry moderately to thoroughlybetween irrigations depending on the plant type and species. Conversely, in times of drought or no rain for prolonged periods, supplemental water will diminish problems associated with heat and sun damage. As a generalrule, watering succulents in well drained soils on a 10 - 14day interval is sufficient to insure plant health and growthduring summer. On heavier soils such as clay soils the watering interval may be decreased. On sandy or very rapidlydraining soils the frequency will have to be increased. Checkthe root zone 2‒3 inches (5‒7.5 cm) below the surface. If thesoil is even slightly damp, wait until it has dried to irrigate.By regularly checking the root zone before watering, youcan get a good idea of your plants’ water needs. A thoroughirrigation followed by a 2-14 day dry period (no rain, nosupplemental water) will give the soil a chance to dry outcompletely which in turn will reduce the incidence of soilborne pathogens. As the daylight decreases in fall and winter, irrigation may be reduced. When nighttime temperatures drop below 60 F. (16 C.), discontinue irrigation; whennighttime temperatures are above 60 F, water as describedabove. Most of these plants can survive on natural rainfallthrough late fall, winter and early spring.Hail damageIn some areas of thedesert southwest, hailstorms cause considerable damage to youngaloe, cacti, agave or othersucculents. Hail damageon barrel type cactus results in wounds at thepoint of impact leavingscars that can vary fromFig. 4. Opuntia pads damaged on one side byvery small spots to largerhail (L) and reverse side (R) undamaged.lesions. On Agave species, leaves may be perforated by the impact of the hail. Whenhail storms are accompanied by strong winds, damage to theplant may be on one side of the plant only (Fig. 4). This distribution of damage is helpful in recognizing hail damage.There is no protection from hail unless plants are coveredbefore a hail storm begins. Small areas or a few specimensmay be covered with a heavy blanket or tarp to minimize thedamage.DiseasesFungal diseases of pads and leavesPhyllosticta pad spotLesions on pads of prickly pear cacti (Opuntia species) may becaused by several different pests or environmental conditions.However, the most common pad spot on the Engelmann’sprickly pear in the desert of Arizona is caused by a species ofthe fungus Phyllosticta. The disease is found throughout the

desert. Lesions are almostcompletely black because ofthe presence of small blackreproductive structurescalled pycnidia producedon the surface of infectedplant tissue (Fig. 5). Sporesproduced within thesereproductive structuresare easily disseminated bywind-blown rain or drippingFigure 5. Phyllosticta pad spot on Opuntia.water and infect new siteson nearby pads. Pads on the lower part of plants are often mostheavily infected since the humidity is higher and moistureoften persists after rain. Once pads dry, the fungus becomesinactive and the lesions may fall out.Severely infected pads or entire plants should be removedfrom landscapes to prevent spread of the fungus. No othercontrols are recommended.Anthracnose of agavesAnother fungus, aspecies of Colletotrichum,causes a disease knownas anthracnose. It canbe a problem on agavesduring moist conditionsor occasionally whenagaves are grown in theshade and overheadirrigated. Infections causelesions on the leavesFigure 6. The anthracnose fungus causesand/or crowns. Whenlesions on Agave leaves in which spores arethe fungus is active, itproduced during wet weather.produces a red to orangespore mass within the lesions (Fig 6). The spores are distributedby splashing water and windborne rain. Leaves with activelesions should be removed. In areas where disease hasoccurred, overhead watering should be avoided. Applicationof fungicides such as thiophanate methyl during wet weathermay prevent new infections, but efficacy of fungicidetreatments has not been established.Other fungal lesionsStem and leaf lesionson cacti and agaves havebeen associated withother fungi as well. Theyusually occur duringprolonged periodsof cool, wet weather.There is a great deal ofvariation in susceptibilityamong Agave species. ForFigure 7. Fungal lesions on Agave weberiexample,severe lesionsdevelop during cool moist weather conditions.have been observed onAgave weberi while other species growing nearby are notaffected (Fig. 7). Species that are susceptible to fungal lesionsshould be replaced withmore tolerant species ofAgave or another type ofplant.Fungal lesions also maydevelop on barrel cacti(Fig. 8). These infectionsusually develop duringspring rains and are morecommon on plants thatare shaded. InfectionsFigure 8. Fungal lesions on barrel cactus.rarely kill the plant butcause irreversible cosmetic damage. If cacti are planted in anarea that is routinely problematic, the plants should be movedif possible. Heavily infected plants should be removed,placed in plastic bags and disposed of in the trash to reducethe spread of the fungi to nearby susceptible plants.Fungal crown rot of EchinocereusSoft rot of several speciesof Echinocereus is caused bya species of Helminthosporium, a fungal pathogen thatproduces airborne sporesabundantly. These sporesare easily disseminated insplashing water and windborne rain. They requirefree water for germinationFigure 9. Crown rot of Echinocereus cactus causes and penetration into thedark sunken areas in which tissue has rotted.host.Most occurrenceshave been in plantings incommercial nurseries onEchinocereus species, butthe fungus is found on padcacti occasionally.Thefirst symptom of infectionis dark, sunken areas thatare soft and water soaked(Fig. 9). In Echinocereus,disease may begin anyFigure 10. Internal rot of Echinocereus cactus. where on the upper partof the cactus and causes aninternal soft rot (Fig. 10). In pad cacti, sunken soft-rottedareas appear on the pad surface.Water management is probably important for preventionof this disease, but to date no research has been done to determine the optimum conditions for disease development.Applications of fungicides such as thiophanate-methyl mayhelp prevent infection where disease has been problematic. Infected plants should be removed so that they are notsources of spores that will infect nearby plants.Pythium rot of barrel cactiAn internal soft rot of barrel cacti is caused by species ofPythium, a soil borne pathogen that is favored by moist conditions (Fig.11). Golden barrel (Echinocactus grusonii) is commonly affected. Pythium sp. can cause root and/or crownThe University of Arizona Cooperative Extension5

rot if plants are placedin the ground too deeplywhen transplanted or arewounded and then overwatered.Barrel cacti should beplanted so that the rootsare placed firmly in thesoil but no soil is placedaround the base of theplant.Care should be takFigure 11. Internal rot of barrel cactus causedentoavoidwounding theby Pythium.fleshy part of the barrelwhen planting. Since the rot is internal, it is often too late totreat cacti once disease is detected. Preventive treatmentsof mefanoxam or phosphytyl-Al may be warranted in valuable species, but the best prevention is proper planting andwatering.Root and crown rot of agavesSeveral soil borne pathogens including a species of thebacterium Erwinia and the fungus Fusarium have been implicated in root and crown rots of agaves. Disease is usually inconcert with infestations by the agave weevil, and currentlyit is thought that weevil feeding enables these pathogensto enter and cause disease when they normally would notbe pathogenic on healthy plants. See the section on agaveweevil for more information on this insect vector. Other thanpreventing wounds in the plant, such as those caused by theagave weevil, there is no control for the bacterial and fungalinfections once the microbes have entered the plant.Bacterial necrosis of saguaroFigure 12. Symptoms of bacterial necrosis ofsaguaro.Figure 13. Bacterial necrosis of saguaro causesexudation of dark brown liquid6Bacterial necrosis ofsaguaro is caused by thebacterium Erwinia cacticida. The initial symptomis a small, light-coloredspot with a water-soakedmargin on the surface ofthe trunk or branches thatmay easily go unnoticed.The tissue under the infection site soon becomesbrown or almost black.As disease progresses, thetissue may crack and exude a dark brown liquid(Fig. 12, Fig. 13). If decayis slow, the tissue maynot have the liquid exudates. As infected tissuebreaks down the woodyskeleton is exposed (Fig.14)The pathogen, E. cacticida, survives in soil orThe University of Arizona Cooperative Extensionplant tissue for long periods of time. The bacterium is spread by insectsand in infested soils.Infections take place atwound sites on roots,trunks and branches, especially those made byinsects, weather-relatedevents, or rodents. Deadand dying plants serve asFigure 14. Bacterial necrosis of saguaro causes reservoirs of the bacteriumsoft tissue to break down leaving only theand as sources of bacterialwoody skeleton.inoculum for new infections. In large natural stands where disease occurs, proximityof saguaros to dead and dying plants significantly influencesmortality.If noticed in time, new infection sites can be treated whenvery small (less than two inches (5 cm) in diameter) by carefully removing the infected tissue, along with a small marginof healthy tissue, using a clean sharp knife. Allow the woundto heal on its own. Older infection sites exuding dark liquid,especially those at the base of the plant, are not treatable.Plants with advancing decay should be removed to preventinfection of nearby saguaros and damage or injury of personsor property. All infested plant material should be completelyremoved from the site and away from any other saguaros.Sammons’ virus of OpuntiaOpuntia Sammons’ virusis common on Engelmannprickly pear (Opuntia englemannii). It causes lightyellow rings with somemosaic pattern in thepads and is often calleda ringspot virus (Fig. 15).The disease is more of acuriosity than a problemsince infections do notFigure 15. Characteristic rings on Opunti padscause noticeable harm toinfected with Sammons’ virus.the plant. The only knownnative hosts are species of Opuntia. Opuntia Sammons’ virushas no known insect vector, but it is sap transmissible. It isa member of the genus Tobamovirus and is closely related toviruses such as tobacco mosaic virus. It is typically spreadby propagating cuttings from infected plants. Do not use infected plants as a source of propagation material. No controlsare recommended.InsectsThere are several insects that can potentially damage manyaloes, cacti, agave and yuccas. Most do not require chemicaltreatment for adequate control. A healthy, non-stressed plantwill withstand the occasional insect pest better than a plantstressed by planting in poorly-drained soil, improper plant-

ing location, and general neglect. Whenever purchasing cacti,agaves or yuccas, examine the plant carefully to avoid bringingthe insects home with you and infecting your other plants.Cholla cacti are attacked by the beetle when the adultslay their eggs, hatch and the larvae burrow into the stems.Waste (frass) is pushed out the entry holes and forms a blackcrusty deposit on the canes. Larvae may burrow into plantroots and cause collapse and death of the plants.Agave Snout Weevil (Scyphophorus acupunctatus)The adult weevil attacks many species of agave. The verylarge Agave americana or century plant is more susceptible toweevil damage than the smaller species. The adult weevilis about ½ inch (12 mm)in length, is brownishblack and has a dullbody (Fig. 16). The adultfemale enters the baseof the plant to lay eggs.Decay microbes also enter through this injuryand as the tissue rots,Fig. 16. Adult Agave Snout Weevil (Scyphophorus the plant has a wiltedacupunctatus). Actual size approximately ½ inch appearance. Infested(12 mm).plants soon collapseand die (Fig. 17). Thelarvae (grubs) develop in the dying plantand infect other hostsnearby. Agave snoutweevil also infests thecanes of several Yuccaspecies.Cactus longhorn beetle is controlled by hand picking theinsects off infested plants. The beetles are most active andeasier to detect and destroy in the early morning or lateevening, especially after warm summer rains. Very spinyspecies are less likely to have damage from the beetle dueto a natural defense by the spines. Chemical control is notrecommended since the populations usually are not highand hand picking is effective.Cochineal scale (Dactylopius coccus)Figure 19. Waxy coat of cochineal scaleControl of the agavesnout weevil is difficult.Fig. 17. Damage to Agave caused by agave Selecting species that aresnout weevil.less susceptible and typically smaller than the century plant is helpful, especially in areas where the problemhas occurred previously. With rare or special specimens,chemical prevention using a broad-spectrum insecticide applied in spring is often effective in reducing damage.Cactus longhorn beetle (Moneilema gigas)Cochineal scale usually can be controlled byusing a strong stream ofwater to wash the insects from the plants. If the infestationis heavy or the insects return, an application of insecticidalsoap may be needed.Figure 20. Red body fluid of the cochinealscale on Opuntia.Plant bugs Alex Wilde 2006The cactus longhornbeetle attacks severalspecies of cacti includingprickly pear and chollacactus(Cylindropuntiaspecies), barrel cactus(Echinocactus and Ferocactus species), youngsaguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea), and others. The adult beetle isFigure 18. Cactus longhorn beetle feeding onabout 1 to 1¼ inches (2.5Opuntia.- 3 cm) long, shiny black,and has distinctive white markings on the antennae. Theantennae are often longer than the overall body length ofthe adult beetle. Damage to the plants is the result of feeding on the margins of prickly pear pads or terminal buds ofother cacti (Fig. 18).Prickly pear (Opuntiaspecies) and cholla cacti(Cylindropuntia species),are attacked by cochinealscale. The insect coversitself with a waxy coatthat makes it appear aswhite cottony tufts attached to the pads andstems of the cacti (Fig.19). To positively identify cochineal scale, crushthe waxy coat with apencil eraser. If the result is a deep red material-actually the body fluid of the insect-then it iscochineal scale (Fig.20).Cochineal scale is usedby native peoples as asource of red dye andalso as a natural foodcoloring in processedfoods.plant1/16a t settepopanytionsinTheFig. 21.Agave plant bug (Cautotops barberi)magnifiedCaulotops barberi, smallbugs measuring about0.6 inches (1.6mm) long,tack agaves and other rosucculents (Fig. 21) Largeulations may be found ongiven plant. The populareach damaging numberslate summer or early fall.bugs feed on leaves andcause a light yellow-tanThe University of Arizona Cooperative Extension7

scar at the point of feeding(Fig. 22). If left untreated,plant will decline andeventually die.theFigure 22. Damage to Agave caused by minuteplant bug.Figure 23. Damage caused by leaf footed plantbug.Caulotops barberi may becontrolled by using insecticidal soap or a broadspectrumornamentalplant insecticide. Chemicals should be applied inearly morning or late evening when the bugs aremost active. Several applications of the insecticidal material may be neededfor complete control.A larger species of plantbug attacks prickly pear(Opuntia spp.) and leaves atan scar at the point of feeding (Fig. 23). The damageis cosmetic but can be reduced by application of insecticidal soap or a broadspectrum insecticide.Coccid scale, soft scaleFig. 24. Coccid scale on Agave spp.Agaves that are stressedare more susceptible tosoft scale (Coccid spp.) Thestress may be the result ofinadequate water or poorgrowing conditions. Neglected plants are mostvulnerable and should beinspected regularly forsigns of all pests. By thetime the scale is discovered, the plant may be irreparably damaged.Scale insects firmly attach themselves to the agave leavesand damage the plant by sucking the plant juices from theleaves (Fig. 24). Soft scales have a flattened, plate-like coverthat, when the insect reaches adulthood, is less than 1/8 inch(3.0 mm) in diameter concealing the actual insect body that isunderneath the ‘shell-like’ cover. If left untreated, the scale willeventually kill the plant or cause enough cosmetic damage tomake the plant unattractive.One option for control of coccid scale is to separate the infected plants from the healthy plants. Provide plants with goodgrowing conditions and proper cultural care and appropriateirrigation, so they are more resistant to scale attack. If the scaleis only attacking an individual plant, discarding the plant isthe best control. When large groups of plants are infected, judicious sprays of a systemic insecticide such as imidacloprid(Merit ) or acephate (Orthene ) are effective. Systemic insec-8The University of Arizona Cooperative Extensionticides are absorbed and moved within plants and as the insectfeeds on the plant they are killed.MitesMites are not insects,but are closely relatedto spiders. Mites arevery small and can beobserved only with amagnifying lens or microscope. The mites thatattack aloe and otherspecies such as Haworthia and Gasteria are eriophyid mites, a group ofFigure 25. Galling and distorted growth of aloeplant-feedingmites thatcaused by aloe mites.often cause galling or abnormal growth of the host plant tissues (Fig. 25, Fig. 26). Unlike their spider mite relatives that have four sets of legs, aloemites have only two sets of legs. They cause malformationsin plants by injecting a chemical that induces galling into theplant tissue. Stems, leaves and f

cacti will yellow, and then die completely (Fig. 2). In freeze-damaged barrel-type cactus, the margins of ribs become straw yellow. If temperatures are not substantially below freezing (a “hard freeze”) and the freeze lasts for only a few hours or less, only the epider-mis may be damaged,