Transcription

February 2013School Choice in the States:A Policy Landscape

AcknowledgementsWe would like to thank Irfan Alibhai for his assistance in thoroughly scouring state policy databases andanalyzing policies for key characteristics, and to Todd Ziebarth at the National Alliance for Public SchoolCharters for customizing NACPS data for this report. We would also like to thank Gary Miron and KevinWelner for their permission to reprint a figure from their informative book, Exploring the School ChoiceUniverse: Evidence and Recommendations.CCSSO’s Research and Development ServiceCCSSO’s Research and Development (R&D) service convenes internal and external expertise aroundstate education leaders’ most essential questions in order to help find the most reliable and actionableevidence to direct state policy development and implementation. A team of external R&D advisors —diverse experts within educational research, development, and practitioner communities — guide R&Dservice activities, which include the following three areas of work: Addressing chiefs’ immediate needsby creating policy-minded research syntheses and roundtables with experts at membership meetings Providing research and development support to the Innovation Lab Networkby facilitating the design and implementation of a plan for research and evaluation Creating a hub for state-level resourcesby organizing internal resources, growing a web presence, and pursuing ways to better connectmembers with external expertiseFor more information about this publication, please contact the author, Jennifer Davis, at jenniferd@ccsso.org.School Choice in the States: A Policy Landscape1

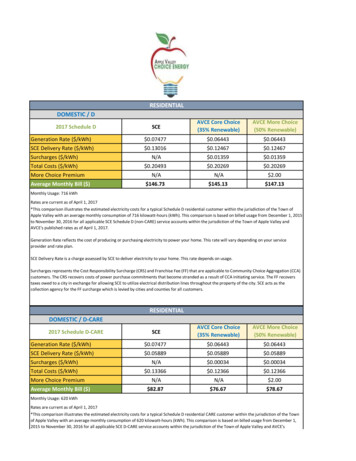

School Choice in the States: A Policy LandscapeExecutive SummaryThe issue of school choice policy – whether and how to offer students the option of attending a school otherthan the one assigned by their residence – is a hotly debated question with substantial implications for chiefstate school officers. In order to provide support to its members around this issue, the Council of Chief StateSchool Officers (CCSSO) seeks to address the often-asked question “What are other states doing?” bycreating an ideologically-agnostic landscape analysis of school choice policies across the states.By highlighting policy coverage and characteristics from best available data across the states and for the fullspectrum of existing school choice options, CCSSO intends to help chiefs contextualize their policy sets withinnational and international trends. The paper does not attempt to comment on which policy trends are favorable,nor does it answer key questions about outcomes or consequences of specific policies within the states.Nevertheless, the policy landscape provides a knowledge base upon which subsequent inquiry can occur.Key findings from the policy landscape analysis includeSchool Choice in the States: A Policy LandscapeGeneral trends2 ll states make at least some alternatives to residence-based enrollment available to at leastAsome students, while no state provides all options to all students. Open enrollment andhomeschooling policies are most common across states; private school voucher and tuitiontax credit policies are least common. Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, and Wisconsin each offer 10 of the 11 types of schoolchoice to at least some students. lthough it is difficult to gauge which states serve the most students through various schoolAchoice policies, Florida and the District of Columbia may be among those with the mostcoverage. States whose policies may cover the smallest percentages of students likelyinclude more rural states such as Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming.Trends in open enrollment Open enrollment is available in some form to at least some students in all states. pproximately 15% of school-age children choose a school other than their school ofAresidence through open enrollment programs. pen enrollment is popular internationally, with 75% of Organisation for Economic CoOOperation and Development (OECD) member and partner nations offering free choice ofpublic schools to all students. Only a small minority of countries restrict this choice withindistricts, municipalities, or regions.Trends in public support for private school choice 8 states and the District of Columbia offer some form of publicly-subsidized support to3students choosing private school, most often in the form of transportation or textbooks.

oucher and tuition tax credit programs are relatively scarce and serve less than a fraction ofVa percentage of all school-age children in the U.S. nly 11 states and the District of Columbia offer voucher programs, which typically targetOlow-income or special-needs students. Wisconsin serves the highest percentage of itsstudent population at 2.7%. nly 14 states provide tuition tax credits for private schooling, most often targeting low-incomeOor special needs students. Among types of tuition tax credits, tax credit scholarships are thefastest-growing. Arizona serves the highest percentage of its student population at 2.8%. Vouchers and tuition tax credits are uncommon internationally.Trends in charter schools harter schools are available in 41 states and the District of Columbia and serve 3.7%Cof students nationwide. The District of Columbia, Arizona, Colorado, Michigan, andDelaware enroll the highest proportions of students in charter schools. ll states with charter schools require the application of state standards and assessments inAcharter schools, and most states require state reporting of student performance data. L ess than half of the states with charter schools require all teachers to be certified withoutexceptions, and half exempt all charter schools from collective bargaining. alf of the states with charter schools restrict growth through caps, although some statesHenable faster growth by allowing more than one authorizing option.Trends in online and virtual schools mong state-sponsored virtual options, full-time multi-district online (FTMDO) schools andAsupplemental state virtual schools are growing in prevalence, but currently only serve afraction of 1% of all school-age children in the U.S. Twenty-four states offer FTMDO schoolsand 30 states feature state virtual schools. Arizona serves the highest percentage of students through FTMDO schools, whileFlorida and North Carolina serve the highest percentages of students through statevirtual schools.Trends in homeschooling Homeschooling is available in all states and serves 3% of U.S. school age children. ost states require parental notification of the intent to homeschool, and a slight majorityMof states also require accountability through testing or professional evaluation. Relativelyfew states (6) mandate additional requirements such as curriculum approval, parentalqualifications, or home visits. omeschooling is relatively uncommon internationally, offered in 53% of OECD memberHand partner nations and covering only 0.4% of students globally. Most countries withhomeschooling require the use of standardized curriculum, while a minority stipulatesemployment and certification standards for homeschoolers.The following pages briefly define each type of school choice and provide further information aboutnational and international trends in policy coverage and characteristics.School Choice in the States: A Policy Landscape 3

IntroductionThe question of whether and how to offer students the option of attending a school other than the oneassigned by their residence is a hotly debated issue with substantial implications for policymaking. Whetherpursued as an effort to increase the availability of high-quality options in communities without equal access;to drive improvement through marketplace competition; or to promote individual liberty, school choiceoptions are undoubtedly increasing across America. Yet in the midst of expansion, the body of researchliterature suggests that the impact of school choice programs on outcomes — such as student success,school and community composition, and system improvement — is poorly understood and can vary greatlyacross programs. Some research shows positive effects, while other research shows negative effects orunintended consequences. Numerous studies show no generalizable effects, suggesting that outcomesheavily depend on context and policy design.Therefore, in order to support its member chief state school officers in making critical decisions aboutschool choice policies, the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) has undertaken an effort toencourage the discussion of school choice policies across its membership. As an initial follow-up to itsrecent policy statement on school choice (below), CCSSO has attempted to address the often-askedquestion “What are other states doing?” by creating an ideologically-agnostic landscape analysis ofschool choice policies across the states. By highlighting policy coverage and characteristics from bestavailable data across the states and for the full spectrum of existing school choice options, the paperintends to help chiefs contextualize their policy sets within national trends. The paper does not attempt tocomment on which policy sets are “right,” nor does it answer questions about outcomes or consequences.Nevertheless, the policy landscape provides a knowledge base upon which subsequent inquiry can occur.School Choice in the States: A Policy LandscapeCCSSO Policy Statement on Opportunities and Options for Students4As state chiefs, we commit to ensuring that every student has access to a high qualityeducation resulting in readiness for college and career. To meet this goal, we will pursueinnovations in policy, practice, and structure to offer high quality options to meet the needs ofall students, regardless of circumstance.Further, we commit to developing and expanding learning opportunities that are notbound by time and place so that all students have opportunity to develop the knowledgeand skills they need. We acknowledge the responsibility of each state to determine theguidance and support that parents and students will need to make decisions about educationalopportunities throughout the K-12 experience. We recognize as well that states believe that itis their responsibility to accelerate all schools toward greatness.CCSSO affirms the authority and responsibility of each state to determine how choicesand options will be made available and to safeguard quality and equity through accountability.CCSSO will provide support, guidance, and information to states as they pursue appropriateeducational options to students within the laws, norms, and contexts of each state.

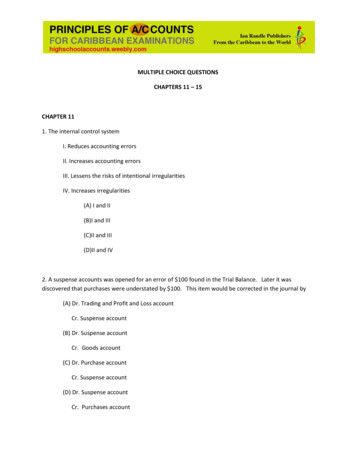

Background: Types and Prevalence of School ChoiceA variety of types of school choice exist today, each with its own rules, target populations, scope,and structures. This paper focuses only on publicly-funded school choice, although a numberof privately funded options exist in every state. Figure 1 illustrates the five main categories andsubcategories that comprise the focus for this landscape analysis. The brief definitions that followdistinguish between the types of school choice and describe their recent penOpen EnrollmentEEnrollnroolllment CharterCharter SchoolsSchools chersVouchechersh tistricistricttricMulti-districtM ltMultii-d-distdistririctctOnlineOnliOnlinene SchoolsSchchoohoolslsPrivatePrivate SchoolSchoolChoiceChoiceTaxTax CreditsCrediCreditsts &&DeductionsDeductDeductionionssVirtualV rtVirtuauall SchoolsSchoSch olhoolssO nlillinOnlineine andand VirtualVirtual SchoolsSchhooollssFigure 1. Conceptual Diagram of School Choice Types Included in the Policy Landscape.Size of individual categorical shapes is not meant to be indicative of program size or scope.Open enrollment describes district or statewide choice programs that permit families to choosea public school other than the one assigned to them by their residence. Interdistrict openenrollment allows families to choose schools in other districts, whereas intradistrict choice allowsfamilies to send their children to a different school within the district. The most prevalent openenrollment schools are magnet schools, which are usually governed by a local school districtboard but may permit either intra- or interdistrict enrollment. Magnet schools often feature atopical or pedagogical focus and receive some supplemental federal funding. Another typeof school that often operates with open enrollment is a Career and Technical Education (CTE)exclusively and enroll students from within or across districts.Open enrollment programs date back to the introduction of alternative schools in the 1960s.Magnet schools rapidly increased in the 1970s and 1980s with the aim of increasing racialintegration. Today, inter- and intradistrict open enrollment plans are the most widespread formof school choice, with close to half of all school districts offering some form of mandatory orvoluntary open enrollment (Miron, Welner, Hinchey, & Mathis, Eds., 2012) in which somewherearound 15% of American school-age children participate. 11Percentage extrapolated from Grady & Bielick (2010).School Choice in the States: A Policy Landscapeschool. Whereas CTE programs may exist within schools, many CTE schools offer CTE courses5

Public support for private school choice describes several means by which states supportstudent attendance at private schools using public resources. States typically provide privateschool choice through voucher programs or tuition tax credits and deductions, althoughadditional state support for private school enrollment may be provided through state-fundedtransportation, textbooks, and learning aides. Voucher programs provide payment for families toenroll their children at a private school of their choice. Very few states currently have operatingvoucher programs, and those that do typically target families with special needs students orlow-income families. Tuition tax credits and deductions provide a less direct (and thereforeoften more politically viable) means for states to use public funding toward private schoolchoice. States may give income tax credits or deductions to families who send their children toprivate school. Alternatively, many states have established so-called “neovouchers” in whicha nonprofit organization is privately established to grant scholarships to students who attendprivate schools. The state then offers tax credits to individuals or corporations who donate tothe scholarship fund.The idea of school vouchers was popularized by economist Milton Friedman and put intopractice in the 1970s, though they were sometimes used as a way to perpetuate segregationthrough vouchers to privately segregated schools. Since then, voucher and tax credit programshave shifted to specifically assist low-income students in urban centers. In the 1990s the firstneovoucher tax credit was created, and it is now growing considerably faster than any other formof private school choice. Still, voucher and tax credit programs together serve a mere 0.3% ofschool age children in the U.S. (Miron et al., 2012).Charter schools are nonsectarian public schools that provide school choice under a charterapproved by an authorizing entity that is either legislatively recognized or publicly appointed.Like conventional schools, charters receive local, state, and taxpayer funds, but they areexempt from many state or local regulations such as those pertaining to enrollment, autonomy,School Choice in the States: A Policy Landscapehuman capital, and so on. In exchange for greater flexibility, charters are held to contractual6performance targets that, if not met, could result in a revoked or non-renewed charter. Thenature of charter contracts and the performance targets therein differs greatly from state to state.The first charter school was founded in Minnesota in 1991. Since then, charters have grown toenroll roughly 3.7% of all public and private school students in the U.S. (Miron et al., 2012).Online and virtual schools fall within the broad spectrum of recently-emerging online programs.Distinguished from supplemental online programs to which students within existing brick-andmortar schools can enroll, which are not within the scope of this landscape, multi-district onlineschools (also known as cyber schools) enroll students full-time and are often either charter- ordistrict-run. By contrast, state virtual schools typically offer supplemental programs to students

who enroll from existing brick-and-mortar schools across the state. Although state virtual schoolsare not full-time, they are included in the policy landscape in response to increasing publicdiscourse around programs of this type. State virtual schools are state-run, unlike single-districtsupplemental programs that are not included in this report.Multi-district online schools are relatively recent choice options, dating to the 1990s and later,and serve only a small fraction of a percentage of school-age children in the U.S. (Watson, Murin,Vashaw, Gemin, & Rapp, 2012). State virtual schools are equally young and similarly low in overallcoverage, and are growing at a slower rate than cyber schools, although the exact number ofstudents served is difficult to discern because enrollment is typically counted by courses ratherthan students. The fastest growing form of online learning is single-district supplemental online orblended programs, but because these are not state-run they fall outside the scope of this report.Homeschooling describes the education of children at home by parents or tutors in the absenceof formal enrollment in public or private schools. States differ in their guidelines or requirementsfor homeschooling as well as the extent to which they provide supplemental resources forhomeschooled children. Homeschoolers may also make use of supplemental online programssuch as state virtual schools. Homeschooling grew in prevalence during the 1980s and wasoffered in all 50 states by the mid-90s (Mead, 2012). As a group, homeschoolers represent theequivalent of 3.4% of all public and private school students (or 3.1% of all school-aged children)(Miron et al., 2012).All together, these various forms of publicly-funded school choice currently serve approximately22% of school-aged children. Figure 2 illustrates the relative prevalence of each school choiceoption in 2011-12, while Figure 3 illustrates relative rates of growth since 1991.Relative student enrollments in publicly-fundedschool choice options, 2010-11Open enrollmentCharter schoolsHomeschoolVouchers & tax creditsOnline & virtual schoolsFigure 2. Relative student enrollments in publicly-funded choice options, 2010-11. Data sources: NationalCenter for Education Statistics (NCES) Common Core of Data (2012); Miron et al. (2012); and Watson et al. (2012).School Choice in the States: A Policy LandscapeTraditional schools7

Enrollment Trends in Publicly-Funded Choice Options9,000,0008,000,0007,000,000Inter- Intra-District Choice6,000,000Homeschooling5,000,000Charter schools4,000,0003,000,000Virtual SchoolsTuition Tax CreditsVouchers2,000,0001,000,00092 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 111- 92- 93- 94- 95- 96- 97- 98- 99- 00- 01- 02- 03- 04- 05- 06- 07- 08- 09- 10919 19 19 19 19 19 19 19 19 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20School Choice in the States: A Policy LandscapeFigure 3. Estimated enrollment trends in publicly-funded choice options in the United States, 1991 to 2011.Reprinted with permission from Miron et al., (2012).8

Trends in School Choice Options Across the StatesOverviewOf the 11 types of school choice included in this policy scan, all states make at least some optionsavailable to at least some students, but no state makes all options availab

include more rural states such as Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming. Trends in open enrollment . Most states require parental notification of the intent to homeschool, and a slight majority . educational options to students within the laws, norms, and contexts of each sta