Transcription

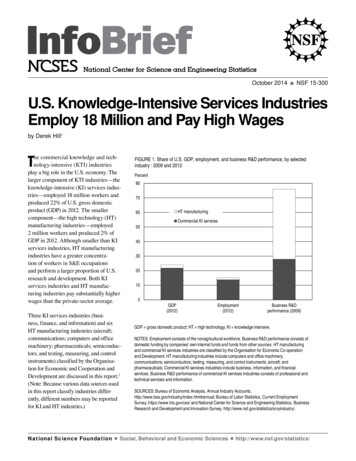

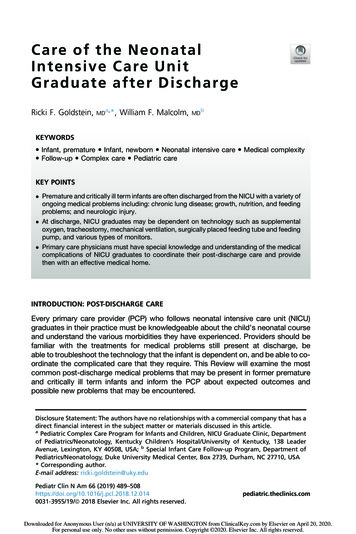

C a re of th e N eo n at alIn t en si ve C are U n itGraduate after DischargeRicki F. Goldstein,MDa,*, William F. Malcolm,MDbKEYWORDS Infant, premature Infant, newborn Neonatal intensive care Medical complexity Follow-up Complex care Pediatric careKEY POINTS Premature and critically ill term infants are often discharged from the NICU with a variety ofongoing medical problems including: chronic lung disease; growth, nutrition, and feedingproblems; and neurologic injury. At discharge, NICU graduates may be dependent on technology such as supplementaloxygen, tracheostomy, mechanical ventilation, surgically placed feeding tube and feedingpump, and various types of monitors. Primary care physicians must have special knowledge and understanding of the medicalcomplications of NICU graduates to coordinate their post-discharge care and providethen with an effective medical home.INTRODUCTION: POST-DISCHARGE CAREEvery primary care provider (PCP) who follows neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)graduates in their practice must be knowledgeable about the child’s neonatal courseand understand the various morbidities they have experienced. Providers should befamiliar with the treatments for medical problems still present at discharge, beable to troubleshoot the technology that the infant is dependent on, and be able to coordinate the complicated care that they require. This Review will examine the mostcommon post-discharge medical problems that may be present in former prematureand critically ill term infants and inform the PCP about expected outcomes andpossible new problems that may be encountered.Disclosure Statement: The authors have no relationships with a commercial company that has adirect financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this article.aPediatric Complex Care Program for Infants and Children, NICU Graduate Clinic, Departmentof Pediatrics/Neonatology, Kentucky Children’s Hospital/University of Kentucky, 138 LeaderAvenue, Lexington, KY 40508, USA; b Special Infant Care Follow-up Program, Department ofPediatrics/Neonatology, Duke University Medical Center, Box 2739, Durham, NC 27710, USA* Corresponding author.E-mail address: ricki.goldstein@uky.eduPediatr Clin N Am 66 (2019) 0031-3955/19/ª 2018 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.pediatric.theclinics.comDownloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on April 20, 2020.For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2020. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

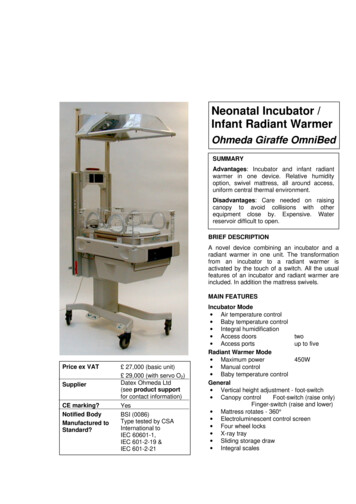

490Goldstein & MalcolmFew outpatient clinics provide comprehensive medical follow-up for the myriad ofmedical problems still present at discharge in NICU graduates. Follow-up clinics forNICU graduates, in general, provide periodic developmental evaluations for highrisk infants and arrange intervention services when needed. A few will offer primarycare and/or more specialized medical care (eg, weaning oxygen, adjusting or weaning off medications), Eligibility for NICU follow-up varies by center with respect togestational age and/or birth weight and/or primary medical problems. However,many NICUs do not have their own follow-up clinic either for medical or developmental care. Instead, multiple subspecialty follow-up appointments are frequentlyscheduled at discharge (Table 1). It then becomes the responsibility of the PCPto integrate information from all subspecialists and coordinate care for the infantand family.1,2Expectations of the PCP and CaregiversExpectations of PCPs who care for medically complex NICU graduates are quite high.These include up-to-date knowledge and understanding of:1.2.3.4.5.Neonatal technologies and therapiesDrug doses and indicationsLaboratory tests that need to be followedIndications for special formulas and recipes for adjusting caloriesVarious types of equipment (supplemental oxygen, nasogastric tube, gastrostomytube [GT], ventriculoperitoneal [VP] shunt, ostomy, pulse oximeter, apnea monitor,tracheostomy, ventilator) and ability to recognize and troubleshoot problemsParents are expected to understand the complex medical problems and needs oftheir NICU graduate, which include:1.2.3.4.5.6.7.Multiple medications with fractional dosing and variable dosing intervalsComplicated feeding strategies and schedules, often throughout the day and nightPoor state regulation and sensitivity to sensory stimulationIncreased susceptibility to infectionMultiple subspecialty appointmentsMultiple intervention services provided in and out of the homeSimultaneously, parents are expected to continue with their prior responsibilities(eg, care for siblings, return to work) despite having little or no respite time. Theymay also be struggling financially because of lost incomeTo provide optimal care for a medically complex infant, the PCP needs to have complete information about all medical problems and expectations at the time ofdischarge. PCPs should confirm that the parents are familiar with this content aswell. A list of this content is included in Table 2. If information is missing from thedischarge summary, the discharging physician should be contacted.RESPIRATORY PROBLEMS AFTER NEONATAL INTENSIVE CARE UNIT DISCHARGERespiratory problems of NICU graduates may be congenital or acquired. Althoughthe etiologies of problems in premature and term infants differ, treatments aresimilar. The most common respiratory problems are the sequelae of prolonged mechanical ventilation (bronchopulmonary dysplasia [BPD] or chronic lung disease)and congenital anomalies of the lungs and airways (congenital diaphragmatic hernia[CDH], tracheoesophageal fistula [TEF], pulmonary hypoplasia, tracheo- and/orbronchomalacia). Pulmonary hypertension may develop and persist in infants withDownloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on April 20, 2020.For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2020. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Care of the NICU Graduate after Discharge491Table 1Subspecialty clinic follow-up for medical problems in NICU graduatesSpecialty ClinicMedical Problems FollowedPulmonaryBronchopulmonary dysplasiaReactive airway diseaseHome ventilator managementInterstitial diseaseCardiologyPatent ductus arteriosusOther congenital heart diseasePulmonary ar diseaseNephrologyHypertensionRenal failureKidney anomalyEndocrineHypothyroidismAdrenal -esophageal refluxCholestatic jaundiceShort gut syndromeConstipationInfectious diseasesCytomegalovirus infectionHerpes simplex infectionOther TORCH infectionsPerinatal human immunodeficiency virus exposurePerinatal hepatitis C exposurePediatric surgeryCongenital diaphragmatic herniaSurgical necrotizing enterocolitisBowel atresiaNissen fundoplicationGastrostomy ral refluxMeningomyeloceleOther genital-urologic malformationOtolaryngologyTracheostomyStridorVocal cord toneal shuntMeningomyeloceleOrthopedic surgeryHip dysplasiaVertebral anomaliesClub footMeningomyeloceleOther skeletal dysplasiaGeneticsSuspected or documented chromosomal syndromeMetabolic disorder(continued on next page)Downloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on April 20, 2020.For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2020. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

492Goldstein & MalcolmTable 1(continued )Specialty ClinicMedical Problems FollowedOphthalmologyRetinopathy of prematurityCortical visual impairmentCataractGlaucomaAudiologyFailed hearing screenRisk of progressive hearing lossPhysical therapyAbnormal muscle tone (decreased or increased)Torticollis/plagiocephalyOccupational therapyBrachial plexus injuryFeeding (oral aversion)Other sensory integration problemSpeech/feedingFeeding problem (dysphagia, swallowing problem)Vocal cord dysfunctionCleft lip and/or palateDietician (often in specialty clinic)Special formulas and/or dietsAdvancement of gastrostomy tube feedsFailure to thriveBPD, CDH, pulmonary hypoplasia or meconium aspiration syndrome. The mostcommon reason for readmission in extremely low-birth-weight (ELBW) infants is respiratory problems.Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia1. Definition of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD)3Table 2Necessary information for PCPs about NICU graduateCategorySpecificsPrescribedmedications Explanation of the “indication” for each medication and the problem it istreating Whether the dose is calculated per kg of weight or is a standard dose What to do if the infant misses a dose or vomits a dose Where and when to refill the medication Whether the medication needs to be adjusted for weight gain and, if so,how oftenFeeding Indications for special formula Mixing instructions for 2, 3, and 4 ounces of formula Name of alternate formula (eg, Neocate/Elecare, Neosure/Enfacare,Alimentum/Nutramigen) to prevent substitution error Local source for special formulas (pharmacy, grocery store) How long special formula should be continued and what formula totransition toSubspecialtyclinicreferrals Which clinic is for which problem? What will be done at first visit (if repeat laboratory tests, can PCP order andsend results to subspecialists)? Which clinic to reschedule immediately if missed (eg, ophthalmology clinicfor active ROP)Downloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on April 20, 2020.For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2020. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Care of the NICU Graduate after Discharge493a. Old versus new BPDi. Old BPD refers to damage caused to lungs and airway by mechanical ventilation and/or oxygen resulting in inflammation and fibrosis. This type of BPDmay occur in premature and term infants, and has been greatly reduced bythe administration of surfactant and high frequency ventilation.ii. New BPD refers to abnormal or arrest in lung development (fewer and largeralveoli) and decreased microvascular development in ELBW infants.b. Premature infants with severe respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary interstitial emphysema, congenital pneumonia, or pulmonary hypoplasia are mostlikely to develop BPD.c. Criteria for diagnosis in premature infants in the Vermont Oxford Network is theneed for supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks post-menstrual age (PMA). Criteriafor diagnosis in the NICHD Neonatal Research Network includes supplementaloxygen or any respiratory support at 36 weeks PMA.4 Therefore, identification ofan infant with BPD may vary from one NICU to another.d. Diuretics and inhaled steroids are sometimes used to treat residual lung inflammation or fluid retention.e. Full-term infants with meconium aspiration syndrome, CHD, or need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for another reason are the most likelyto need treatment for BPD after discharge.f. All infants with BPD are at increased risk of lower respiratory tract infections andneed for rehospitalization during the first year of life.g. Reactive airway disease (RAD)i. Infants with BPD have a high risk of developing RAD in infancy, and asthmain later childhood.ii. The most common symptoms are tachypnea either at rest or with exertion.iii. Occult RAD (ie, without wheezing) may be diagnosed based on response toa trial of bronchodilator treatment or results of pulmonary function testing.h. Chronic home ventilation after dischargeInfants with severe BPD may require placement of a tracheostomy for prolongedmechanical ventilation at home. Timing of tracheostomy and age of discharge for infants receiving chronic mechanical ventilation varies among NICUs and often dependson the infant’s clinical course, health care provider preferences, ability of the family tocare for the infant at home, and medical resources (eg, home health nursing) in thecommunity.Congenital Anomalies of the Lungs and Airways1. CDH/pulmonary hypoplasiaa. CDH occurs when there is a defect in formation of one of the diaphragms, leading to herniation of the abdominal viscera into the pleural cavity on that side.This prevents normal growth and maturation of the lung parenchyma and pulmonary vasculature. This “hypoplasia” of the lungs results in pulmonary hypertension (PHTN) because of thickening of the muscular coat of arterioles, makingthese vessels more reactive to hypoxemia and acidosis. It is not a reason forpremature birth (although it is often diagnosed in utero), so most infants areborn at term or near term.b. Infants with CDH may recover completely after initial treatment in the NICUwithout residual lung problems, but most will develop some degree of chroniclung disease and have persistent PHTN requiring supplemental oxygen andother medications after discharge.Downloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on April 20, 2020.For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2020. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

494Goldstein & Malcolmc. Infants with premature and prolonged rupture of membranes often developsome degree of pulmonary hypoplasia due to oligohydramnios, which preventsnormal growth of the lungs in utero. Premature infants born with pulmonary hypoplasia often require prolonged mechanical ventilation, develop significantBPD, and have associated PHTN. They are frequently discharged on supplemental oxygen and other medications.2. Tracheoesophageal fistulaa. TEF is a congenital malformation of the trachea and esophagus.b. There are three types of TEF, the most common being esophageal atresia with afistula between the trachea and lower esophagus.c. Repair of this defect sometimes results in tracheal stenosis or an area of tracheomalacia (collapse) at the fistula site causing prolonged stridor.3. Tracheo- and/or bronchomalaciaMalacia or collapse of the proximal (trachea) or distal (bronchial) airways canresult in stridor and increased work of breathing. This may be secondary totracheal repair (as in TEF) or caused by an intrinsic weakness of the airwaysupporting structures. Airway malacia almost always improves with growthof the child but may require prolonged ventilatory support (tracheostomy) during infancy and early childhood.Pulmonary Hypertension1. Some infants with severe BPD will develop secondary PHTN requiring increasedoxygen and treatment with vasodilators (most commonly inhaled nitric oxideacutely followed by sildenafil chronically).2. PHTN may develop before or after discharge from the NICU.3. Infants with CDH or other etiology for pulmonary hypoplasia also often have significant PHTN requiring prolonged treatment after discharge.4. Diagnosis of PHTN is made by evidence of increased pulmonary artery pressure(right ventricular hypertrophy, flattening of the intraventricular septum, tricuspidvalve regurgitation) evident by echocardiography or cardiac catheterization.5. This serious complication of BPD and other respiratory problems in term andpreterm infants needs to be followed closely by a pediatric cardiologist and/orpulmonologist. Infants with PHTN will require periodic echocardiograms todetermine if medications and oxygen should be weight adjusted or may beweaned.6. Chronic aspiration (secondary to gastro-esophageal reflux disease [GERD] or swallowing problem) and infection should be prevented because they can exacerbatePHTN.Follow-up of Infants with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia1. Infants with BPD with or without PHTN (ie, home on supplemental oxygen) shouldbe followed in an NICU Graduate Clinic, and/or by a Pediatric Pulmonary Clinic, todetermine when supplemental oxygen and medications should be adjusted orweaned.a. Good growth and medical stability should be established before decreasing thetreatment.b. Oxygen is often weaned off first during the day and then at night.c. Infants who are unable to wean from oxygen as expected, should be evaluatedfor PHTN, if not already diagnosed.2. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) prophylaxis with Synagis.3a. Eligibility for RSV prophylaxis changes each year. The most recent criteria are:Downloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on April 20, 2020.For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2020. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Care of the NICU Graduate after Discharge495i. Infants born 28 weeks gestation who are less than 12 months oldii. Infants less than 1 year old with hemodynamically significant congenitalheart diseaseiii. Children less than 2 years old with BPD who continue to require medicalintervention (supplemental oxygen, chronic corticosteroid, or diuretictherapy)iv. Children with pulmonary abnormality or neuromuscular disease that impairsthe ability to clear secretions from the upper and lower airways in the firstyear of lifeb. Influenza vaccine––all infants with BPD greater than 6 months of age and theirimmediate family and other caretakers should receive a flu shotFEEDING, GROWTH, AND NUTRITION IN THE NEONATAL INTENSIVE CARE UNITGRADUATEFeeding problems in the NICU are frequently a barrier for discharge.5,6 These difficultiesoften persist, or even worsen, once the infant has transitioned to the home environmentand are among the most common parental stressors post-discharge.7 Whetherthese feeding problems are caused by physiologic immaturity in premature infants,comorbidities of prematurity, or a complication of an underlying diagnosis requiringNICU admission (eg, respiratory, cardiac, neurologic, genetic), they are also a primaryreason for readmission.8–10 It is important for the PCP to be aware of the differentstages of feeding skills and factors that may interfere with their normal progression.Common Feeding Problems by Age (Age Corrected for Prematurity in PrematureInfants)Birth to 3 months:1. Oral feeding skills are driven by primitive reflexes. Rooting, sucking, and swallowing are the basic skills newborns possess to breast or bottle feed shortly after birth.Protective reflexes including gagging, coughing, and the laryngeal chemoreflexprovide safety measures to allow for successful early feeding.2. Any disturbance in the autonomic nervous system, as may be seen in extremelypremature birth or neurologic injury, may interfere with this involuntary process.3. Comorbidities such as BPD, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), or GERD that mayinterrupt normal breathing and feeding schedules (eg, nil per os, continuous feedings), may negatively impact the natural progression of early feeding.3 to 6 months:1. Feeding becomes a voluntary activity. Primitive reflexes integrate with brain development and the upper aerodigestive tract grows to resemble that of an adult by5 months of age. With this, along with developing head control, a transition to solidfoods is supported.2. The infant must now coordinate the movement of food from the anterior oral cavityto the posterior pharynx to swallow, a much different eating pattern than suckingliquid from a nipple directly into the pharynx.3. Oral exploration is abundant (hands, feet, clothing, toys to mouth) and works todesensitize the tongue to accept more textured foods.4. Delays in head control or gross motor skills, as well as negative oral experiences(eg, orogastric and endotracheal tubes, suctioning, GERD), may disrupt this transition to voluntary feeding and may lead to oral aversion or difficulty in transition totextured foods.Downloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on April 20, 2020.For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2020. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

496Goldstein & Malcolm6 to 9 months:1. Infants begin eating thicker solids and finger foods, further increasing sensory stimulation with visual

1. CDH/pulmonary hypoplasia a. CDH occurs when there is a defect in formation of one of the diaphragms, lead-ing to herniation of the abdominal viscera into the pleural cavity on that side. This prevents normal growth and maturation of the lung parenchyma and pul-monary vasculature. T