Transcription

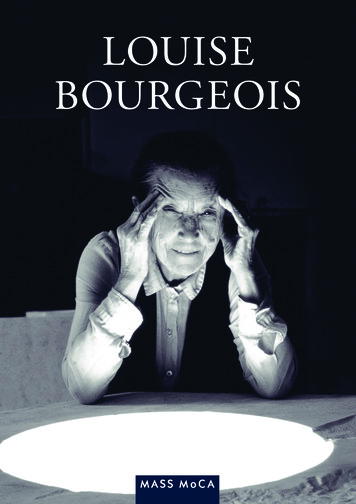

LOUISEBOURGEOIS

“My subject is therawness of the emotions,the devastating effect ofthe emotions you gothrough. The materialsare my medium.”1One of the most influential artists of the twentiethcentury, Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) is knownfor incorporating psychological and biographicalelements into her highly evocative, richly layeredworks. Transforming her emotional life intophysical form, the artist took as her subjects theintimacies and traumas of childhood, marriage,motherhood, and artistic struggle. The range ofthose thoughts and emotions are reflected in thevariety of materials that she utilized in her art.Her expansive practice included drawings andpaintings, as well as sculptures in plaster, wood,fabric, latex, glass, bronze, and the marble featuredat MASS MoCA. Bourgeois’s use of both soft andhard, warm and cold materials—what the artistmight have described as female and male, passiveand active—adeptly articulate the polarities thatBourgeois navigated through her art. She wasintrigued by the subconscious, and her work isoften understood as an expression of repressedfeelings—from anger, to fear, love, and desire.Bourgeois was in psychoanalysis for 30 years anddescribed her artistic practice as an attempt to workthrough whatever tumult plagued her—likeningher process to an exorcism of pain and the past.Bourgeois chose whichever medium best expressedwhat she needed to say. She began working withmarble in the late 1960s, first visiting Carrarain 1967 to work with the region’s famous stone.Later, in the 1980s, she began shipping stones toNew York. Bourgeois was attracted to marble forits ability to transform from an inert block intosomething else through the force of her unconscious.PASS, 1988 – 1989Marble; 50½ 48 37 inchesCollection Louise Bourgeois TrustPhoto: Peter Bellamy, The Easton FoundationLicensed by VAGA, NYThe difficulty of working in marble also appealedto her. She said of hard materials:“ the resistance of the material is part ofthe process I can express myself only in adesperate fighting position.”2Yet her mastery over the stone is evident, and thematerial is uniquely suited to Bourgeois’s interest informal ambiguity, able to seem as soft and suppleas skin, or retain the heavy, coarse look of raw stone.The centerpiece of the current exhibition is animmense untitled work dated 1991–2000.Standing over six feet tall, it is composed of twoelements which together weigh over 15 tons. Thesculpture has the rusticated texture of punchedmarble, and in its size and totemic presence it takeson the feel of an ancient monument. Two large,smooth orbs, each with a circular hollow in itscenter, sit atop each section like a pair of eyes orbreasts, testicles, or heads, each referent

encouraging another, possibly conflictinginterpretation of the work. Large spirals are carvedinto the sculpture’s side, and smaller spirals seemto grow out of bulbous protrusions along its topedge. The artist has emphasized the importance ofthe spiral in her work on numerous occasions,describing it as a twist that reminds her of wringingout wet fabric as a child, dreaming of wringingthe neck of her father’s mistress.3 She has alsocompared it to “controlling chaos.” There are twodirections to a spiral, she noted. “Beginning at theoutside,” Bourgeois explained, “is the fear of losingcontrol; the winding in is a tightening Beginningat the center is a representation of giving, andgiving up control; of trust, positive energy, oflife itself.”4 In Untitled, the artist has doubled thespiral, creating the symbol of eternity. Pairs andmirrored imagery recur throughout Bourgeois’spractice, and suggest various relationships andcouplings—from the self/other to husband/wife,parent/child, mother/father. Together but separate,the two elements in Untitled might seem to suggestthe fear of separation and abandonment thatBourgeois indicated is within all her work. Untitledmakes its United States debut at MASS MoCA,along with a dramatic history. The sculpture wascreated from the remains of an earlier relatedwork which was badly battered and damagedbeyond repair when it was caught in a terriblestorm at sea upon its return to New York fromEurope. Bourgeois salvaged the marble andcarved the current version of the work. Ratherfittingly, the artist once again transformed lossinto new sculpture.UNTITLED, 1991 – 2000White marble, two elements; 1st: 73 74 115 inches; 2nd: 80¾ 43½ 100 inchesCollection Louise Bourgeois TrustPhoto: Christopher Burke, The Easton Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, NY

Nature Study (Velvet Eyes), 1984Marble and steel; 26 33 27 inchesCollection of Michael and Joan Salke / Salke Family TrustPhoto: Allan Finkelman, The Easton FoundationLicensed by VAGA, NYWhile Bourgeois grappled with weighty subjects,her work can also be full of humor. In NatureStudy (Velvet Eyes), for example, a smooth pairof eyes peers out at us from deep holes cut ina rough slab of marble. Hovering betweensentience and objecthood, the work is slightlyunsettling, yet unequivocally whimsical. Theeyes are almost cartoonish—reminiscent of theplastic adhesive “googly eyes” that can humanizenearly any object.Across the gallery, PASS (1988–89) is similarlyambiguous. It seems to oscillate between a skulllike face and genitalia. The vertical slit at thecenter resembles both a nose cavity, phallus, orvulva and clitoris—the circular caverns near thetop, eyes, or testicles. The two sculptures, bothmade in Bourgeois’s Brooklyn studio, are in partabout seduction, referencing the act of makinga pass at someone and the inherent tensionimplied in this exchange. Offering viewersappealingly suggestive forms and references,Bourgeois’s marble sculptures ultimately refuseany single interpretation, dwelling instead inprovocative uncertainty.Outside the main gallery, a fourth work madefrom polished aluminum functions as bothcounterweight and complement to the trio ofmarble sculptures. In contrast to the heavy stoneworks firmly planted on the ground, the delicate,reflective sculpture The Couple is suspended fromthe ceiling from a single cable. Bourgeois mademany hanging works, which she felt articulated afragile, ambivalent state. Two figures are entwinedin a twist of metal, their feet and legs peeking outfrom the bottom of what might resemble anunruly skein of yarn or surreal jumble of extendedappendages. Bourgeois said of this work:“The figures in the hanging The Couplehold onto each other. Nothing will separatethem. It is a precarious and fragile state Despite all our handicaps, we hold ontoeach other. It is really the Other that interestsme. It is an optimistic view. Locked together,they spin for eternity.”5Together, the intimate selection of worksillustrates the power of Bourgeois’s unique workto articulate the ineffable fervencies of anguishand passion that define the human condition,and to picture the yawning desire for connectionthat keeps our ultimate solitude at bay.– Susan Cross1 “Louise Bourgeois in Conversation with Christiane MeyerThoss,” in Christiane Meyer-Thoss, Louise Bourgeois:Designing for Free Fall, Zurich: Ammann Verlag, 1992, p. 123.2 Quoted in “Taking Cover: Interview with Stuart Morgan,”first published in Artscribe, January 1988, reprinted inMarie-Laure Bernadac and Hans Ulrich Obrist, eds. LouiseBourgeois: Destruction of the Father/Reconstruction of theFather, Writings and Interviews 1923 – 1997, London: VioletteEditions, 2007 (1st ed: 1998), p. 155.3 See Paul Gardner, Louise Bourgeois, New York: Universe,1994, p. 68.4 Louise Bourgeois, “Self-Expression is Sacred and Fatal,” inChristiane Meyer-Thoss, Louise Bourgeois: Designing for FreeFall, p. 179.5 Louise Bourgeois, March 8, 2002, statement in response tosculpture (LBQ-0010); The Easton Foundation.

Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) was born inParis to parents who ran a tapestry restorationworkshop. In her youth she helped with thefamily business, making drawings of areasthat needed to be repaired. She studied artin several locations, including the École duLouvre, École nationale supérieure desBeaux-Arts, Académie de la Grande Chaumière,Académie Julian, and in the studio of FernandLéger. In 1938 she married the art historian,Robert Goldwater, and moved to New YorkCity, where she continued her studies at theArt Students League and exhibited withthe American Abstract Artists Group as earlyas 1949, befriending artists including Willemde Kooning, Mark Rothko, and Franz Kline.She also met many of the European expatswho fled to New York during World War II.In 1957 Bourgeois became an American citizen.Although she exhibited throughout her career,Bourgeois’s work did not fit neatly withinthe dominant movements and was not widelyknown early in her life. She was 70 years oldat the opening of her retrospective at theMuseum of Modern Art, New York, in 1982.Her radical engagement with the body andpsychology has had an immense impact onensuing generations of artists. She wasawarded the National Medal of the Arts in1997, and today her work is in the permanentcollections of major museums including theCentre Pompidou, Paris; Solomon R.Guggenheim Foundation, New York andBilbao; the Hirshhorn Museum and SculptureGarden, Washington, D.C.; MoMA, NewYork, NY; the Tate, London; and the WhitneyMuseum of American Art, New York, NY.Louise BourgeoisOn view beginning May 28, 2017Major exhibition support is provided by Joan andMichael Salke.cover:Louise Bourgeois in her studio with Pass in 1988.Photo: Claudio EdingerArt: The Easton FoundationLicensed by VAGA, NYinside flap:The Couple, 2007–2009Cast and polished aluminum, hanging piece; 61 30 26 inchesCollection Louise Bourgeois TrustPhoto: Christopher Burke, The Easton FoundationLicensed by VAGA, NY1040 MASS MoCA WayNorth Adams, MA 01247413.MoCA.111massmoca.org

1040 MASS MoCA Way North Adams, MA 01247 413.MoCA.111 massmoca.org Louise Bourgeois On view beginning May 28, 2017 Major exhibition support is provided by Joan and