Transcription

Developing a Framework for Effective Financial Crisis ManagementbyDalvinder Singh and John Raymond LaBrosse This article discusses the roles and responsibilities of the various agencies that are part of the financial systemsafety net, and it sets out a framework for the decision-making process for these actors in the management of afinancial crisis. In this context, the article discusses issues of micro- and macro-prudential oversight and argues thatmore needs to be done to ensure accountability, independence, transparency and integrity of the various actors of thefinancial system safety net.JEL Classification: G15, G21, G28.Keywords: Banks, Contingency Planning, Financial Crisis Management, Financial System Safety Net, FinancialStability, Micro- and Macro-prudential Regulation, Systemic Risk. Dalvinder Singh is associate professor at the University of Warwick, School of Law and John RaymondLaBrosse is an honorary visiting fellow at the University of Warwick, School of Law. The authors aregrateful to Kendra LaBrosse and Christian Mecklenburg-Guzmán for their assistance with the tables anddiagrams. Dalvinder would particularly like to thank Christian for his research assistance for this paper.The authors also would like to thank Sebastian Schich, Rodrigo Olivares-Caminal, David Mayes, andCharles Enoch for comments and suggestions. All views and indeed errors are the authors‘ responsibility.The article was released in December 2011. The work is published on the responsibility of the SecretaryGeneral of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflectthe official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries.

DEVELOPING A FRAMEWORK FOR EFFECTIVE FINANCIAL CRISIS MANAGEMENTOECD work on financial sector guaranteesOECD work on financial sector guarantees has intensified since the 2008 global financial crisis as mostpolicy responses for achieving and maintaining financial stability have consisted of providing new or extendedguarantees for the liabilities of financial institutions. But even before this, guarantees were becoming aninstrument of first choice to address a number of financial policy objectives such as protecting consumers andinvestors and achieving better credit allocations.A number of reports have been prepared that analyse financial sector guarantees in light of ongoing marketdevelopments, incoming data, discussions within the OECD Committee on Financial Markets. The reports showhow the perception of the costs and benefits of financial sector guarantees has been evolving in reaction tofinancial market developments, including the outlook for financial stability. They are available atwww.oecd.org/daf/fin. Financial safety net interactions Deposit insurance Funding systemic crisis resolution Government-guaranteed bank bonds Guarantees to protect consumers and financial stabilityAs part of that work, the Symposium on ―Financial crisis management and the use of governmentguarantees‖, held at the OECD in Paris on 3 and 4 October 2011, focused on bank failure resolution and crisismanagement, in particular, the use of guarantees and the interconnections between banking and sovereign debt.Conclusions from the Symposium are included at the back of this article. This article is one of nine prepared forpresentation at this Symposium.2 Managing crises without guarantees: How do we get there? Costs and benefits of bank bond guarantees Sovereign and banking debt interconnections through guarantees Impact of banking crises on public finances Fault lines in cross-border banking: Lessons from Iceland The macro-prudential authority: Powers, Scope and Accountability Effective practises in crisis management The Federal Agency for Financial Market Stabilisation in Germany The new EU architecture to avert a sovereign debt crisisOECD JOURNAL: FINANCIAL MARKET TRENDS – VOLUME 2011 ISSUE2 OECD 2012

DEVELOPING A FRAMEWORK FOR EFFECTIVE FINANCIAL CRISIS MANAGEMENT1 IntroductionPublic confidence plays an important role in sustaining financial system stability. Innormal times the regulation and supervision of banks, the promotion and use of standards ofsound business and financial practice, central bank actions, explicit deposit protection andan effective bank closure mechanism all help to reduce the adverse consequences of afinancial crisis emanating from bank failures. It is understood that banks, like other firms,will fail1 and the likelihood of this happening is higher when risks in a particular bankingconcern are not managed appropriately, bubbles in certain markets burst or financialmarkets are very fragile due to either domestic or foreign reasons. In almost allcircumstances private sector solutions, such as rights issues or mergers, should be pursuedin the first instance to deal with problem or failing banks, as in most cases they can limit thepressure on the financial system safety net (FSN). However, when problems becomesystemic governments tend to play a much more active role and call upon the agencies thatmake up the FSN to undertake extraordinary measures. Intervention can take a variety offorms. As such, there is a clear need for officials to undertake coherent contingencyplanning, financial risk assessment and crisis management. A significant development onthat front has been the introduction of financial stability forums in the form of committeesin individual countries to oversee agencies within the official safety net and improve howthey govern macro-prudential and micro-prudential issues (Nier et al 2011).2 However,financial stability committees are not new and the reinvigoration of a formal oversight bodyis unlikely to fulfil all that is expected of it. This gives rise to an expectations gap, whichwe explore.It is trite to say, but financial market crises occur on a regular basis with similar causes,as explained by Reinhart and Rogoff (2009); however, recent experience suggests that verylittle attention has been given to how best to manage them. One explanation could be thatone crisis seems to lead to another, so it is difficult to determine the endpoints. Anotherexplanation might be that crisis management needs more attention so that lessons learnedcan be incorporated into improved techniques to minimise the effects of catastrophicevents. Notwithstanding the fact that a considerable amount has been learnt about crisismanagement from past experiences, lessons from the past seem to be amiss in terms ofguiding future directions, so the risk of repeating mistakes arises.This article focuses on measures used to contain a financial crisis, and generally takesaccount of events in the European Union (EU). We review the experience of the crisis sofar and seek to draw some conclusions on how it was overseen and managed based on thatanalysis. Section 2 sets out the main structure of a FSN and describes how the mandates,roles and responsibilities of the agencies within it tend to change during the course of acrisis. Attention is also given to the interests and impact that stakeholders, in themarketplace outside the FSN can have during a bank failure or financial disaster. The papersets out why careful attention to the FSN and the market stakeholders is now quiteimportant. Recent experience offers many examples of the need for more clarity in themanagement of a crisis. To help policy-makers a decision tree is offered and explained insection 3 as an alternative to the spurt of ad hoc pronouncements that have done little morethan confuse markets and undermine the public‘s confidence in policy-makers. One of theclear messages is the need for more effective oversight of micro- and macro-prudentialfactors. But more effective oversight is not enough, as noted by the IMF, without attentionto the need to ensure accountability, independence, transparency and integrity (Ingves andQuintyn 2003). In section 4, with the EU experience in mind, we examine the tools used tocontain a financial crisis. Section 5 considers the usefulness of a micro- and macroprudential system of oversight to contain a crisis before we set out a means to bridge theOECD JOURNAL: FINANCIAL MARKET TRENDS – VOLUME 2011 ISSUE2 OECD 20123

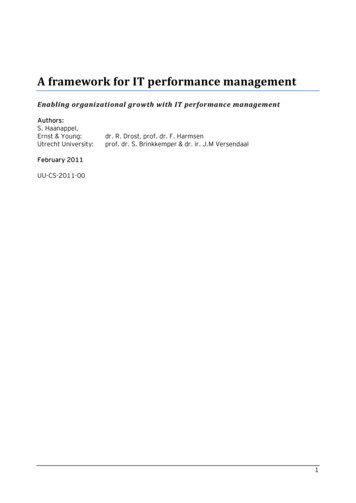

DEVELOPING A FRAMEWORK FOR EFFECTIVE FINANCIAL CRISIS MANAGEMENTgap with the introduction of some form of financial stability oversight body. Someconclusions are offered in the final section of the paper.2 Reflections on the FSN Players: Their Roles and Responsibilities in PromotingFinancial System StabilityThe financial crisis that began in 2008 demonstrated severe weaknesses in the FSN(FSAP, 2010; IMF 2010; LaBrosse and McCollum 2011). While the deficiencies wereevident almost worldwide, the most severe problems were found in European markets,largely due to the lack of coordination, consultation and development of coherent strategiesto deal with the crisis (European Commission, 2010a, 2010b). For those reasons it isimportant to know at the outset what organisations should be included in an FSN, includingtheir roles and responsibilities, and why the interests of other stakeholders are also quiteimportant. In basic terms the question becomes: who should be included in the officialsafety net and deemed the core stakeholders in the financial system? The answer isimportant because during a crisis there needs be a high level of consultation, coordinationand cooperation between the various interested parties. Figure 1 sets out the official safetynet players, showing how their influence in decision-making and management of issueschanges through a time spectrum.The Official Safety Net PlayersThe FSN has traditionally included a lender of last resort (central bank), prudentialregulation (by a bank supervisor), a government department (Ministry of Finance orTreasury) and explicit deposit protection (insurance or other form of a limited guarantee)(Financial Stability Forum 2001; Schich 2009). But the recent financial crisis underscoredthat the group of official safety net players has become somewhat more elastic. There is aneed to consider the roles of the legislative body, non-bank regulators such as securitiescommissions, housing agencies and insurance company regulators, as decisions that theytake can have an important impact and threaten financial system stability. Moreover, thereare compelling reasons to consider other stakeholders and bring them into the dialogue sothat financial system stability can be addressed more effectively and efficiently. The rolesof shareholders, external auditors, the courts and credit rating agencies need to beappreciated and understood better in the pursuit of financial system stability as externaldecisions by those parties can have a direct impact on the official safety net players’response to safeguard system stability. This is not to suggest that they reside in the FSN,but to ensure the FSN is able to respond proactively rather than reactively to instil a betterdegree of confidence in the financial system.4OECD JOURNAL: FINANCIAL MARKET TRENDS – VOLUME 2011 ISSUE2 OECD 2012

DEVELOPING A FRAMEWORK FOR EFFECTIVE FINANCIAL CRISIS MANAGEMENTFigure 1: Official Safety Net PlayersThe Official Safety NetNormal timesDepositCentral ulatory andTreasury supervisory frameworkfor banks & non-banksPaymentSystemsCrisis TimesDepositInsuranceCentral ntor/SystemsDepositInsuranceRegulatory andsupervisoryTreasuryframework forbanks & nonExpertbanksCommitteesAftermathDepositPayment InsuranceSystemsCentral Bank/FinancialStabilityLegislativeGuarantees onToxic Assets BodyExpertCommittees Regulatory andsupervisoryTreasuryframework forbanks & non-banksThe Ministries of Finance, or Treasuries, take a particular interest in the efficientfunctioning of FSNs. During relatively stable times the Treasury sets tax policy, manages acountry’s finances, is the steward of the government’s accounts and provides advice onfinancial sector policy issues. In light of these tasks it has oversight responsibility formonetary and economic policy. The role of the Treasury inevitably brings it under thesurveillance of the IMF and into OECD forums, where its performance is assessed on aregular basis. Broadly speaking the Treasury will act in good faith in terms of how itmanages a country’s finances. The exercise of its discretion can and may well be directedby the government with limited autonomy or, as in the case of Germany, the right to vetogovernment decisions on public finances.The Treasury‘s role in terms of financial sector policy development is broadly speakingone of oversight, with responsibility for monetary policy and financial regulation andsupervision delegated to other organisations within the FSN. In the context of the euro areathe European Central Bank (ECB) has the mandate for setting monetary policy. In othercountries monetary policy is delegated to the central bank and the functions of regulationand supervision to a different department of the central bank or a separate authority.International forums for policy discussions on financial matters are technically theresponsibility of the Treasury, but it may have the central bank, the prudential supervisorand the deposit insurer by its side. In most instances the prudential supervisor has directresponsibility for day-to-day oversight of the financial system, and may be able to initiatechanges in regulatory policy with relative independence once the regulatory architecture isagreed by the government and a country‘s legislative body. The gaps in financial regulationcould reasonably be laid at the door of the Treasury since it is its role to initiate reform inthis area, which in practical terms leads it to rely on its central bank and prudentialsupervisor and perhaps other regulators for advice. Moreover, the move towards macroand micro-prudential regulation highlights a need for a holistic approach to themanagement of financ

planning, financial risk assessment and crisis management. A significant development on that front has been the introduction of financial stability forums in the form of committees in individual countries to oversee agencies within the official safety net and improve how they govern macro-prudential and micro-prudential issues (Nier et al 2011).2 However, financial stability committees are not .