Transcription

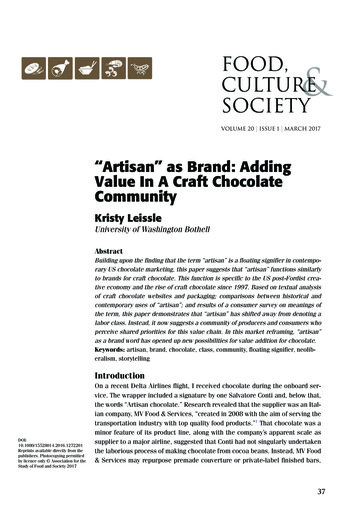

Food,CultureSociety&VOLUME 20 ISSUE 1 MARCH 2017“Artisan” as Brand: AddingValue In A Craft ChocolateCommunityKristy LeissleUniversity of Washington BothellAbstractBuilding upon the finding that the term “artisan” is a floating signifier in contemporary US chocolate marketing, this paper suggests that “artisan” functions similarlyto brands for craft chocolate. This function is specific to the US post-Fordist creative economy and the rise of craft chocolate since 1997. Based on textual analysisof craft chocolate websites and packaging; comparisons between historical andcontemporary uses of “artisan”; and results of a consumer survey on meanings ofthe term, this paper demonstrates that “artisan” has shifted away from denoting alabor class. Instead, it now suggests a community of producers and consumers whoperceive shared priorities for this value chain. In this market reframing, “artisan”as a brand word has opened up new possibilities for value addition for chocolate.Keywords: artisan, brand, chocolate, class, community, floating signifier, neoliberalism, 1272201Reprints available directly from thepublishers. Photocopying permittedby licence only Association for theStudy of Food and Society 2017On a recent Delta Airlines flight, I received chocolate during the onboard service. The wrapper included a signature by one Salvatore Conti and, below that,the words “Artisan chocolate.” Research revealed that the supplier was an Italian company, MV Food & Services, “created in 2008 with the aim of serving thetransportation industry with top quality food products.”1 That chocolate was aminor feature of its product line, along with the company’s apparent scale assupplier to a major airline, suggested that Conti had not singularly undertakenthe laborious process of making chocolate from cocoa beans. Instead, MV Food& Services may repurpose premade couverture or private-label finished bars,37

K. Leissle “ARTISAN” AS BRANDboth common practices. Alternatively, it may employ workers to make chocolate. If so, then what meaning of “artisan” is shared between Salvatore Contiand, say, Art Pollard of Amano Artisan Chocolate? Pollard, an early entrantto the current US craft revival and among its most decorated, makes limitedbatches of chocolate largely by himself, starting with cocoa from growers hehas vetted and to whom he sometimes brings finished bars.2US chocolate makers today self-name as “artisan” to distinguish their production ethos from that of multinationals that have dominated the industryfor a century. When I encountered the term on what was, without question, amass-produced item intended for global distribution, I considered the possibility that “artisan” had become a floating signifier. My subsequent analysis of“artisan” on product packaging and websites suggested that “artisan” indeedfloats in chocolate marketing discourse, such that even a mass-produced itemcan claim “artisan” qualities without disrupting any material or labor classreferent.“Artisan” does, however, play an important role in value addition. Drawingon the works of Adam Arvidsson (2006), Naomi Klein (2002), and Celia Lury(2004, 2009), I suggest that “artisan” functions similarly to brands for contemporary US chocolate. Of course, “artisan” is different from brands in someways. For example, “artisan” is not the property of one corporate entity; manymanufacturers apply the word to both foods and non-food products. However,brands also stretch beyond the original product to which they attached; withsimilar elasticity, “artisan” shares a functional purpose with brands, addingvalue to goods that are marketed as such. My analysis demonstrates how themeanings of “artisan” have multiplied in craft chocolate marketing, breakingfrom the historical understanding of “artisan” as a labor class. This multiplicityof meaning allows “artisan” to work as a brand word, simultaneously addingand reflecting new value for chocolate, especially within the reframed craftmarket in which it most often appears. This brand function emerged as theword shifted away from signifying a class of workers, and encompassed insteadthe notion that buying and selling “artisan” chocolate signals participation ina community of likeminded people—a “brand community” (Arvidsson 2006, 5).This is possible because while “artisan” has detached from any fixed meaning, the word still seems meaningful, embedded as it is within a discursivevehicle that offers it (and to which it offers) shape and sense. That vehicle isstorytelling, the most common feature of “artisan” chocolate marketing. Indeed, with 78 percent of “artisan” makers prominently sharing the story ofhow and why they engage in the craft, it seems almost requisite that a maker’spersonal motivations and experiences accompany the word. These stories havevarious loci of meaning (that broadly correspond to the priorities of foodies[Johnston and Baumann 2010], though others are possible), but collectivelythey support “artisan’s” role as a resource that consumers and producers useto convey information, ideas, and even ethical positions about chocolate. Inthis way, the value of “artisan,” as with brands, is that the term becomes an“object of possibility”—not fixed, but “rather, open, extending into—or better,38

implicating—social relations” (Lury 2004, 1–2). Ultimately, the purpose of “artisan” today is that the word extends and reinforces the idea and practice of acommunity of real people who communicate through the exchange of chocolate,and appreciate it, in both personal and value-added senses.Market Context and MethodsVOLUME 20ISSUE 1MARCH 2017This function breaks with the historical application of “artisan” to a labor class,and is specific to the post-Fordist creative economy in the US today. Whileglobal companies do use “artisan,” as discussed above, the term appears mostfrequently in the textual discourse of recently established craft makers, a groupthat has neither an agreed nor imposed definition. The sole attempt to delineate“craft” for the US was made by the Craft Chocolate Makers of America, nowlargely inactive, but which originally invited in makers that processed betweentwo and 200 tons of cocoa each year. To map contemporary meanings of “artisan,” I first needed a working definition of “craft” to demarcate the recentmarket entrants that primarily claim the term. My intention was neither to distinguish “artisan” from “craft,” nor to conflate these. Instead, I was interestedin how craft makers use “artisan.” For this research, I defined “craft” as: (1)maker starts with cocoa beans and produces finished chocolate (“bean to bar”maker); (2) company is not one of the “Big Five” multinationals (Allen 2009)3;(3) company or its bean to bar practice was established during the recent waveof innovation, since around 1997. As of August 2015, I recorded 129 US companies that met these criteria.4Among them, nearly half used “artisan” in textual discourse. Craft makerssend various signals that their chocolate is not mass-produced, including thelabel “artisan,” but also “small-batch,” “handcrafted,” or even “American.” Twomethodological notes follow. The first is that while other terms may play asimilar role to “artisan,” I analyzed “artisan” because it has specific historicalmeaning and thus a definition against which to assess its contemporary function. The second is that while “artisan” reflects craft makers’ general priorityto differentiate from “industrial,” all analyses of and references to “artisans” inthis paper include only craft companies that used the term in textual discourse;I excluded makers that fit my craft criteria, but did not use “artisan,” or suggested artisanry only in imagery.5The discursive multiplicity and community-building potential of “artisan”must be understood vis-à-vis recent growth in the craft market segment. In1997, the near hundred-year dominance of multinationals Hershey’s and Mars(Brenner 1999) started to give way, when Scharffen Berger opened its doorsin California as the country’s first new bean to bar chocolate maker in fiftyyears. Scharffen Berger, which “led this country’s contemporary resurgence inartisan chocolate-making,” introduced a distinct range of chocolates, virtuallyunknown in the previous century;6 companies have since sprung up nationwide,offering novel bars.San Francisco’s Dandelion Chocolate explains how this “New AmericanChocolate” differs from that which came before:39

K. Leissle “ARTISAN” AS BRANDMany people don’t realize it, but most of the world’s chocolate is industrial . Any big company is going to have different priorities than a small one,and for industrial chocolate the goals are consistency and low cost. It’s amiracle of manufacturing that a candy bar can be so inexpensive and tasteexactly the same as any other one. However, it doesn’t have to be this way.7Indeed, the US has exploded with makers who eschew “consistency and lowcost” in favor of an “artisan” approach. These are often small-scale operations;some involve just one maker, or family-and-friend partnerships. Unlike largecorporations, which develop brands through consumer research and makethem visible through advertising, chocolate “artisans” rarely have a marketing budget. However, journalists and retailers use “artisan” frequently, givingit scope and reach beyond the means of any one company. Even if a makerdoes not self-name as such, a Google search of the company plus “artisan”almost unfailingly returns results, often local newspaper articles celebratinga neighborhood maker.8 Online sales channels regularly advertise “artisan”chocolate.9 Festivals make free use of the term: Northwest Chocolate Festivaladvertises as “The Nation’s Premier Artisan Chocolate Festival” (October 3–4,2015), whereas “Fine Artisan Events Proudly Presents The Chicago ArtisanChocolate Festival” (April 16–17, 2016).To analyze use of the term, I employed a mixed-methods approach. Throughtextual analysis of websites and packaging, I gathered contextual meaningsof “artisan” among US craft makers. My goal was neither to demonstrate allmeanings nor to suggest that a common definition is necessary. Rather, similarto Matthias Hofferberth’s recent (2015) meaning-mapping for the term “globalgovernance,” I suggest that discursive multiplicity enables “artisan” as a valuable term for imagining and practicing a chocolate community.As Dandelion’s “New American Chocolate” suggests, craft chocolate is arecent US phenomenon. My analysis of “artisan” locates its use within the laborpossibilities and foreclosures that the breakdown of the Fordist contract hasengendered. Whereas post-Fordism for many US workers has meant erosionof union-derived benefits and loss of manufacturing jobs, for others (perhapsfewer in number) post-Fordist work regimes have been associated with therise of the creative economy, including possibilities for artisanry. Charles Heying’s account (2010) of Portland, Oregon as an “artisan economy” is a usefulstarting point. Equally usefully, Heying offers a rare contemporary definitionof “artisan” products. I undertook a close reading of Heying’s definition, to assess whether and how “artisan” chocolate makers met his criteria; my findingssuggest that “artisan” chocolate only partially fulfills them. However, Heying’saccount of Portland helps delineate a community where post-Fordism has allowed new productive forms to flourish, despite (or perhaps as a result of)curtailment of US labor support more broadly.If the value of “artisan” lies, similarly to brands, in “the productive potential that [it] has in the minds of consumers” (Arvidsson 2006, 74), I neededinsight into how consumers make sense of the term. I surveyed approximately40

VOLUME 20ISSUE 1one hundred attendees at the 2014 Northwest Chocolate Festival, a group of“interested” consumers,10 for their understandings of “artisan.” My respondentsample better matched the socioeconomics of foodies, who report six-figureaverage incomes and whose discourse is racialized as white (for example, inthe preponderance of white celebrity chefs on the Food Network [Johnston andBaumann 2010, 16]), than Seattle demographics. Respondents were 81 percent white, compared with 70 percent in Seattle; reported an average annualincome of 115,000, compared with the Seattle median of 67,100; and wereon average 36 years, slightly older than the most populous Seattle age bracketof 25–34.11 Some 57 percent of respondents identified as female, 41 percent asmale, and 2 percent as other gender expression.The Northwest Chocolate Festival was an ideal site for investigating “artisan” as informational interface between the business of selling chocolate andcommunity meaning-making. As Director of Education for the four festivalsfrom 2010 to 2013, I observed rising consumer attendance (from about 2000 to10,000) and an increasing educational atmosphere. While tasting chocolate remained a key attraction, by 2012 the festival offered over 80 talks and demonstrations (more than any similar event), and average attendance at a talk was89 (range: 20–250). Makers routinely expressed that they made the typicallylong-distance trip to Seattle because “everybody else was there.” Attendancefor both makers and consumers thus signaled participation in a community thatwas making meaning around chocolate.In festival and similar settings (for example, farmers’ markets), “artisan”becomes an informational resource for “‘negotiation[s]’ of the self in relation tothe shifting demands of everyday life” (Arvidsson 2006, 5). Such negotiationsare consistent with the neoliberal context within which US craft chocolate ismaturing. “Artisan’s” various meanings unfailingly make sense in an ideologicallandscape in which institutions recede and individuals, using the market mechanism to assess a range of life choices, command attention and significance(Larner 2000; Lemke 2001; Rose 1999). “Artisan” thus has i

artisan chocolate-making,” introduced a distinct range of chocolates, virtually unknown in the previous century; 6 companies have since sprung up nationwide, offering novel bars. San Francisco’s Dandelion Chocolate explains how this “New American Chocolate” differs from that which came before: 40 K. Leiss L e “ART is AN” A s BRAND Many people don’t realize it, but most of the .