Transcription

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODEARTICLES 3 AND 4 2018 CUNADEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS5-1

Section 5 – Uniform Commerical CodeArticles 3 and 4The UniformCommercial CodeNone would argue that the UnitedStates of America is a world leader whenit comes to commerce. A great manyfactors contribute to our status as acommercial giant, but perhaps no singlefactor has had as large an impact oncommerce in this country as the UniformCommercial Code, more commonlyreferred to as the “UCC,” or simply the“Code.”But what exactly is the UCC? It is thebody of “law” which provides the rights,duties, responsibilities, and liabilities ofparties to virtually every kind of commercial transaction. The word “law” appearsin quotation marks because the UCC isnot a true law in and of itself. The UCCoperates more as a guideline from whicheach of the state legislatures has enacted its own laws governing commercewithin its borders.The UCC has been in formal existencesince 1952. It is the product of the jointefforts of the American Legal Institute(ALI) and the National Conference ofCommissioners on Uniform State Laws(NCCUSL). Since its original enactment,the UCC has undergone — and will continue to undergo — many changes andrevisions. Each time an article of the UCCis revised, it is up to each state to amendits own laws if it chooses to do so.The Code is at present divided into 11sections: 2018 CUNADEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONSArticle 1:General ProvisionsArticle 2:SalesArticle 2A: LeasesArticle 3:Negotiable InstrumentsArticle 4: Bank Deposits andCollectionsArticle 4A: Funds TransfersArticle 5:Letters of CreditArticle 6:Bulk TransfersArticle 7: Warehouse Receipts,Bills of Lading, and OtherDocuments of TitleArticle 8:Investment SecuritiesArticle 9:Secured TransactionsIn this section we will discuss someof the provisions included in Article 3,Negotiable Instruments and Article 4,Bank Deposits and Collections. We willattempt to cover the provisions that aremost likely to have a regular impact oncredit union operations. As such, thisis not intended to provide an exhaustive review of all of Articles 3 and 4. Itis intended as a tool to be used in yourdaily operations, to assist you in understanding the credit union’s rights as provided in the Code.Again, the UCC is not, of itself, thelaw of the land. Each state and theDistrict of Columbia have passed theirown versions of the Code. Happily, mostof the provisions in the various stateUCCs are, indeed, identical to those wewill discuss. But this guide should notbe relied upon to ascertain your legalstatus with respect to a specific com-5-2

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4mercial transaction. When problemspresent themselves in the area of commercial law, you should look to yourspecific state’s statute — and yourcredit union’s attorney — to determineyour rights, duties, and responsibilities. That having been said, the specificreferences to the Code throughout thischapter and the next refer not to anyparticular state’s code (unless otherwiseindicated), but rather to the UniformCommercial Code as adopted by the ALIand the NCCUSL.General Background ofUCC Articles 3 and 4The body of law that has evolved intopresent-day UCC Articles 3 and 4 actually had its origin in the Middle Ages.Merchants, traders, and the like learnedthat it was indeed a dangerous world.One could simply not afford to risk traveling the seven seas in search of commercial transactions while carrying one’sgold. To solve this dilemma, these merchants devised a system of paying forgoods with paper rather than coin.Merchants discovered that they couldsell their goods and, rather than accepting gold — or any other type of tangiblepayment — they could direct their buyerto use a written instrument pledging apayment to a third party, or “payee.”The merchant could then, as the system developed, use that instrument tosatisfy some debt he owed another bytransferring the ownership of the instrument to his creditor. That creditor coulddo the same until eventually the instrument found its way to and was paid bythe original buyer. In essence, a single 2018 CUNADEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONSinstrument could be used to conduct aseries of transactions without the needfor cash.Over time this written instrumentcame to be known as a draft. A typicaldraft involves three parties: “drawer,”“drawee,” and “payee.” The merchantwas the drawer — he used the instrument to draw upon the debt owed bythe buyer. The buyer, then, became thedrawee. And the merchant’s creditorbecame the “payee” of the draft. Theact of the payee signing over the draft toanother creditor in the chain came to beknown as “endorsement,” and the transaction between two parties in the chainwas referred to as “negotiation.”By the beginning of the eighteenthcentury, a similar type of instrumentwas widely in use — the “note.” Anote is simply a promise by one party(the “maker”) to pay another person(the “payee”). It wasn’t long beforenotes became negotiable in much thesame fashion as drafts. Throughout thecourse of the 18th and 19th centuriesEnglish and American judges developedthe common law relating to negotiableinstruments. The courts understoodthat a cornerstone of the success of thecommercial system was the protectionof the good-faith purchasers of notesand drafts. As we will address belowin our discussion of Holders in DueCourse, generally speaking, a good-faithpurchaser of a negotiable instrumentis protected from nearly all claims anddefenses which might otherwise be usedto prevent him from receiving payment.Here in the U.S., Congress began itsefforts at regulating the payment systemduring the 19th century. During the firsthalf of the century, state banks issued5-3

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4notes that were used like money in commerce. Human nature being what it is,there were more than occasional abuses.Some banks began issuing notes thatwere really not backed by sufficientcash — others made their notes redeemable only at remote branches, secure inthe knowledge that nearly no one wouldjump through the necessary hoops toobtain his payment. In an attempt tobring about order in what was developing into a rather chaotic scene followingthe Civil War, Congress imposed a taxon state bank notes in order to encourage more widespread use of the “greenbacks” then issued by national banks.This might have been disastrous forthe state banks had they not managedto introduce Americans to checkingaccounts as a means to make payments. Of course, Americans have beenusing checking accounts ever since, inincreasingly greater volume.A “check” is simply a draft that isdrawn on a bank, thus the common lawwhich had developed around negotiableinstruments applied to most aspects ofpersonal check transactions. The process of collecting checks evolved intoa series of private agreements betweenbanks.As things progressed, subtle differences evolved in the case law of individual states with respect to negotiableinstruments law and bank collectionlaw. By the end of the 19th century, itwas clear that some uniformity had tobe brought into the system so partiesto interstate transactions could be reasonably certain of their rights, duties,and responsibilities. In 1896, theNational Conference of Commissionerson Uniform State Laws sponsored the 2018 CUNADEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONSNegotiable Instruments Law (NIL) — thepredecessor to today’s UCC Article 3 —and it was eventually adopted by everystate. But the NIL did not regulate checkcollections.In 1913 the Federal Reserve wasestablished. One of its purposes was tostandardize the check collection system in order to improve its efficiency.Ultimately the Federal Reserve playeda great role in simplifying the routingof checks by providing a more efficientclearinghouse to compete with the private banking system. But what aboutthose banks which chose not to belongto the Federal Reserve System? Manyefforts to develop a model code governing check collections outside the federalsystem were attempted with varying levels of success. The most successful, theBank Collection Code (BCC) of 1928,was adopted by only 18 states.In 1940, the NCCUSL resolved toreplace all of its various uniform acts(including the NIL) with a centralized,comprehensive commercial code. TheAmerican Legal Institute joined in theeffort, and the UCC was born. Article3, then entitled “Commercial Paper,”and Article 4, “Bank Deposits andCollections,” formed the cornerstoneof the laws governing negotiable instruments and check collections. As mentioned, Articles 3 and 4 were eventuallyadopted by every American jurisdiction.Throughout the last half of the 20thcentury commerce has evolved — attimes outgrowing various provisionsthroughout the UCC. As such, manyof its articles have undergone revisionthrough the years, including Articles 3and 4. Others have been added — mostsignificantly for our purposes, Article5-4

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 44A in 1989, which is devoted to electronic funds transfers (we will discussArticle 4A in more detail in the next section of this module). The most recentof those revisions was made in 1990,at which time Article 3 was rewritten(and given its present name, NegotiableInstruments) and Article 4 was substantially revised.Article 3 of the Code is broken intosix parts. Part 1 addresses general provisions and definitions; Part 2 deals withthe concepts of negotiation, transfer,and endorsement; Part 3 is devoted tothe enforcement of negotiable instruments; Part 4 speaks to the liability ofparties to transactions involving negotiable instruments; Part 5 deals withthe dishonor of negotiable instruments;and Part 6 addresses discharge and payment (and is beyond the scope of thismanual).Article 4 contains five parts: Part 1addresses general provisions and definitions; Part 2 discusses the collectionof items with respect to depositary andcollecting banks; Part 3 deals with collection of items with respect to payorbanks; Part 4 addresses the relationshipbetween payor banks and their customers; and Part 5 discusses the collectionof documentary drafts (which is beyondthe scope of this module).In the pages that follow, we willreview details of these various parts.Again, the intent of this module is notto provide the reader with the definitivesource of information regarding thesetwo articles. Our goal is to highlightsome of the more prominent aspects ofvarious parts of these articles in termsof our daily lives managing the affairs of 2018 CUNADEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONScredit unions.Note: Each section of the UCC,as adopted by the NCCUSL and theALI, was accompanied by an “OfficialComment.” While these comments havenot been enacted by state legislatures,judges and lawyers frequently rely onthem as they attempt to resolve matters under the various Code provisions.We will occasionally refer to the OfficialComments (or simply “comments”)throughout this section and the next.UCC Article 3:Negotiable InstrumentsPart 1— General provisionsScopeArticle 3 applies to “negotiableinstruments,” defined in §3-104 assigned writings that order or promise thepayment of money (a more detailed definition of “negotiable instruments” canbe found below). This article does notapply to “payment orders,” which aregoverned by Article 4A, nor does it applyto securities transactions. Securitiestransactions are governed by Article 8of the U.C.C. and are beyond the scopeof this manual. The comment to §3-102acknowledges that occasionally a particular writing may fit the definition ofboth a “negotiable instrument” underArticle 3 and an “investment security”under Article 8. In those cases, Article 8is controlling.A number of terms used throughoutthe UCC are given very specific meanings within the Code. Article 3 is noexception to that general premise.5-5

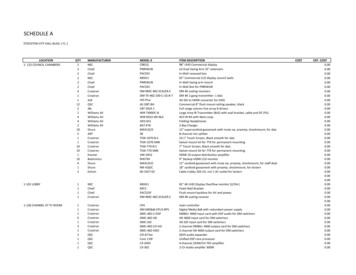

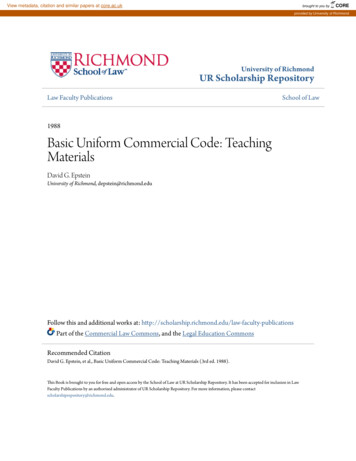

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4Level Two§3-103 sets forth several definitionswhich we will briefly discuss throughoutthe context of this chapter. Wheneverattempting to wind your way throughArticle 3, it is quite useful to bear inmind that most of the terms in the article have these specific meanings.order to pay a fixed amount of money,with or without interest or other chargesdescribed in the promise or order, if allof the following apply:Negotiable instruments It is payable on demand or at a definitetime.As we’ve discussed, a negotiableinstrument is a signed writing thatorders or promises the payment ofmoney. More specifically, §3-104defines the term “negotiable instrument” as “an unconditional promise or It is payable to bearer or to order atthe time it is issued or first comes intopossession of a holder. It does not state any other undertakingor instruction by the person promisingor ordering payment to do any act inaddition to the payment of money.Refer to figure 5.1 for an illustrationFigure 5.1 The Personal CheckFigure 5.1 The Personal Check1252John DoeDateJane A. Doe1234 1st StreetThe City, MI 98765Pay to theOrder of(Order to Pay)(Payee's Name)(Sum Certain Alpha)Credit Union (Payor Bank)AddressCity, State Zip CodeMemo Sum Certain NumericDollars(Drawer's intointoaanegotiablenegotiablein thiscase,the mostkind �� instrumentin this case,—themostcommonkindcommonof negotiableby credit unions: ocreateanegotiableinstrument,it state whopersonal check. In order to create a negotiable instrument, it must be an order to pay; it mustmust be an order to pay; it must state who is to be paid (the “payee”); it must state a sumis to be paid (the “payee”); it must state a sum certain; it must identify who is ordered to pay (the “payorcertain; it must identify who is ordered to pay (the “payor bank”); it must become payablebank”);mustbecome payableon oridentifyafter a specifieddate; it themustidentifythe party makingon oritaftera specifieddate; it mustthe party makingorder(the “drawer”);and the ordermust be signedthe drawer.(theit “drawer”);and itbymustbe signed by the drawer. 2018 CUNANegotiable instruments — also referred to in the Code simply as “instruments”— are divided into two primary categories: drafts and notes. A draft is aninstrument that is an order to pay (for example, a check or share draft drawn on acredit union), while a note is an instrument that is a promise to pay (such as atypical installment loan). Because the primary emphasis in this manual is the lawwith respect to the deposit side of credit union operations, our review of Article 3will focus on its application to drafts as opposed to notes.The comment to revised Article 3 makes clear that a credit union share draftfallsACCOUNTwithin REGULATIONSthe meaning of the word “check” — thus credit union share drafts mayDEPOSITbe referred to as “checks” for purposes of the UCC. In fact, Article 3 includes creditunions within the definition of the term “bank.” Although there are important5-6

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4of the most common type of negotiableinstrument, the personal check.Negotiable instruments — alsoreferred to in the Code simply as “instruments” — are divided into two primarycategories: drafts and notes. A draft isan instrument that is an order to pay (forexample, a check or share draft drawnon a credit union), while a note is aninstrument that is a promise to pay (suchas a typical installment loan). Becausethe primary emphasis in this manual isthe law with respect to the deposit sideof credit union operations, our review ofArticle 3 will focus on its application todrafts as opposed to notes.The comment to revised Article 3makes clear that a credit union sharedraft falls within the meaning of theword “check” — thus credit union sharedrafts may be referred to as “checks” forpurposes of the UCC. In fact, Article 3includes credit unions within the definition of the term “bank.” Although thereare important distinctions between credit unions and banks, it is quite useful totreat them as synonymous terms underthe Code, to help ensure a uniform operation of the nation’s checking accountsystem.To whom is an instrument payable?The payee of an instrument is the person to whom an instrument is payable.Typically, a cursory review of a checkwill reveal the party to whom it is payable. But occasionally that is not readilyapparent. §3-110 addresses a numberof different scenarios to assist the creditunion in determining who is entitled tothe payment of an instrument.First and foremost, this section makesclear that the person to whom an instru- 2018 CUNADEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONSment is initially payable is determinedby the intent of the person signing as theissuer of the instrument (for example,the “drawer”). In the rare instance thatmore than one person signs as a drawer,and not all of the signers intend thesame person as payee, the instrument ispayable to any person intended by one ormore of the signers.Occasionally, the individual to whoman instrument is payable will not beidentified by name. This is not necessarily fatal to the issue of whetherthe instrument is negotiable. §3-110provides that the payee can be identified “in any way, including by name,identifying number, office, or accountnumber.” §3-110(c). If the instrumentis payable to an account identified bynumber and to a named person, thenamed person is entitled to paymenteven if he is not the owner of the identified account. §3-110(c)(1).Section 3-110 addresses other fairlyrare situations as well. It makes clearthat if an instrument is payable to atrust, an estate, or a person describedas the trustee or representative of a trustor estate, the instrument is payable toeither the trustee, the representative, ora successor of either, regardless whethera beneficiary or estate is also named inthe instrument. §3-110(c)(2)(i). Further,it provides that if an instrument is payable to a person described as the agentor representative of another namedperson, the instrument is payable to theagent/representative, his successor, ordirectly to the represented person.(§3-110(c)(2)(ii))The same section provides that ifan instrument is payable to a persondescribed as holding an office, the5-7

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4instrument is payable to the named person, the incumbent of the office, or asuccessor to the incumbent.(§3-110(c)(2)(iii))Multiple payeesThe 1990 revision to Article 3 clarified an ambiguity in the law with respectto multiple payees. A check payable to“John Doe or Jane Doe” can be paid toeither John or Jane Doe. If a check ispayable to “John Doe and Jane Doe,”neither John nor Jane Doe can receivepayment without the signature of theother. Those provisions are not new.But Revised Article 3 addressed for thefirst time the situation where the words“and” or “or” do not appear. If, forexample, a check is payable to “JohnDoe, Jane Doe,” Revised Article 3 provides that it is payable to either John orJane Doe. §3-110(d).At least one court has even heldthat the use of a forward slash betweennames on a check made that checkpayable to either party. In that case,three checks payable to “San FranPlumbing, Inc./Danco, Inc.” werecashed by a bank even though theendorsements of Danco, Inc., (unbeknownst to the bank, of course) wereforged. A New Jersey court held that thechecks were properly payable to eitherparty in the alternative — since SanFran Plumbing, Inc., did, in fact, negotiate them, that negotiation was proper.In the words of the court: “The short,slanting stroke is called a ‘virgule,’ andin modern usage is equivalent to theword ‘or.’ Further, an ambiguous copayee designation should be consideredto be in the alternative.” Danco Inc. v.Commerce Bank/Shore, N.A., 29 UCC 2018 CUNADEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONSRep Serv 2d 513, 290 NJ Super 211,675 A2d 663.Essentially, the Code has placed theburden of clearly expressing the intention that a check be negotiated by all ofthe named payees on the person issuingthe instrument. As a practical matter,many credit unions routinely require thatall named parties in such cases endorsethe instrument. Although this is not arequirement under the Code, such a policy could help the credit union avoid finding itself in the middle of a feud betweenJohn and Jane Doe at a later time.Conflicting amounts — whichone controls?A typical check presented at thecredit union for deposit will include thewords “Pay to the order of.” along withan individual’s or organization’s name oraccount number, followed by a numericexpression of the amount of payment.The check will also then spell out theamount of the payment using words (forexample, “Ten Thousand Dollars andNo Cents”). Suppose a check containsan inconsistency between the numericamount and the spelled-out amount?Section 3-114 provides that in such acase words prevail over numbers. Thusa check payable to the order of JohnDoe orders the payment of “ 1,000”(numeric) and “Ten Thousand Dollars”(spelled-out), it is properly payable inthe amount of ten thousand dollars.Statute of limitationsPrior to Revised Article 3, the issue ofwhen the statute of limitations expiredin an action to enforce an instrumentwas less than clear. Under the 19905-8

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4revision, a party entitled to payment ofa personal check must now bring a lawsuit to enforce the payment within threeyears after the check has been dishonored or 10 years from the date the checkwas issued, whichever occurs earlier.Part 2 — Negotiation, transfer,and endorsementNegotiation“Negotiation” of an instrumentmeans a transfer of possession of theinstrument, by a person other than theissuer, to another person. The person towhom this transfer is made is known asthe “holder” of the instrument. Exceptfor a transfer made by a remitter of acashier’s check or teller’s check — forexample, the person who purchases oneof those instruments but makes it payable to another party — if an instrumentis payable to an identified person, it cannot be negotiated without the transfer ofpossession and the endorsement by theholder. An instrument that is payable tobearer (for example, an instrument thatdoes not name a payee, but is ratherpayable to anyone who has possession ofit) can be negotiated simply by transferof possession. §3-201.TransferUnless two parties have otherwiseagreed, if an instrument is transferredfrom one party to another for value, but thetransferor neglects to endorse the instrument, the person to whom the instrumentwas transferred has the right to force thetransferor to supply his endorsement.§3-203. However, in such a case, negotiation does not take place unless and untilthe endorsement is made. 2018 CUNADEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONSEndorsement“Endorsement” generally means asignature (other than the signature ofthe maker, drawer, or acceptor) on aninstrument for the purpose of negotiating it or restricting payment of theinstrument. The Code provides for different types of endorsements. An endorsement is a “special endorsement” if itincludes the signature of a holder andidentifies a person to whom the instrument will then be made payable. Forexample, if a check is payable to JohnDoe, and he endorses it “Pay to theorder of Jane Doe” and signs his name,John Doe has made a “special endorsement.” The check is then payable only toJane Doe (who, in turn, can add her ownspecial endorsement). §3-205(a).If the holder simply signs his namewith no other instructions or wording,the endorsement is known as a “blankendorsement.” A check endorsed inblank becomes payable to anyone wholater comes into its possession unlessand until someone adds a specialendorsement. §3-205(b).An endorsement which purports tolimit payment of an instrument to aparticular person is generally not effective in stopping further transfers. Forexample, if a check is endorsed “PayJane Doe Only,” Jane Doe may negotiate the check to subsequent holderswho may then disregard the restriction.§3-206(a).Another type of restrictive endorsement, which is a frequent cause forconcern, involves a payee endorsing acheck “Pay to the order of Jane Doe, intrust for Jim Doe.” Suppose in a caselike this that Jane then endorses thecheck in blank, and delivers it to another5-9

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4individual, a depositary bank, or thebank on which it was drawn, for payment. The Code makes clear that, unlessany of these parties has notice that Janehas breached any fiduciary duty owedto Jim, they can safely pay Jane. If anyparty has notice that Jane is using thefunds for her own personal benefit, thatparty could be liable to Jim if they paythe check to Jane. §3-206(d).Part 3 — Enforcementof instrumentsThe “Holder in Due Course” doctrineGenerally speaking, any holder of aninstrument is entitled to its enforcement. There are, however, severaldefenses to the payment of an instrumentwhich can be raised by the obligor (theperson obligated to make the payment).Consider, for example, the case of thesale of goods between two parties — callthem Smith and Jones — where Smithhas agreed to purchase goods from Jonesand Jones has agreed to accept paymentby personal check. In this example, withrespect to the personal check, Smithis the obligor and Jones is the obligee.Let’s suppose further that Jones neverdelivers the goods. His failure to deliverthe goods provides a defense to Smith,and he can stop payment on the checkwithout incurring liability to Jones (stoppayment orders are addressed below inour discussion of Article 4).But what if, prior to Smith’s realization that the goods would not be delivered, Jones negotiated the check toWilson? Will Smith be entitled to raisethe same defense against Wilson as hecould against Jones? The short answeris: It depends. 2018 CUNADEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONSWhether Smith can raise a defense topayment of the personal check againstWilson depends on both (a) the typeof defense he seeks to raise; and (b)whether or not Wilson is a “Holder inDue Course.”A “Holder in Due Course” (we’ll referto it as an HIDC) has special rights toenforce an instrument. To put it anotherway, HIDC-status limits the types ofdefenses to payment that can be raised.A holder of an instrument becomes anHIDC if and only if 1) at the time theinstrument is issued or negotiated to theholder it does not bear “such apparentevidence of forgery or alteration or is nototherwise so irregular or incomplete asto call into question its authenticity”(§3-302(a)(1)); and 2) the holder tookthe instrument: For value. In good faith. Without notice that the instrumentwas overdue or had been dishonoredor there was an incurred default withrespect to payment of another instrument issued as part of the same series. Without notice that the instrumentcontained an unauthorized signatureor had been altered. Without notice of any claim to a property right or possessory right in theinstrument §3-302(b).At the risk of oversimplification, thinkof a Holder in Due Course as an innocent, impartial bystander to the primaryobligation between two parties — agood-faith purchaser with special powers.The types of defenses that can beraised by an obligor are divided into two5-10

SECTION 5 – UNIFORM COMMERICAL CODE ARTICLES 3 AND 4important categories: “real defenses,”and all others (sometimes referred toas “personal defenses”). An obligor hasa “real defense” to the payment of aninstrument based on any of the following: Infancy of the obligor, to the extentthe age of the obligor is a defenseto a simple contract (in most states,a minor can void a contract until hereaches the age of majority — typicallyage 18). Duress, lack of legal capacity, or illegality of the transaction which underother law nullifies the obligation of theobligor (for example, if a contract wassigned at gun point, it would probablybe considered to have been signedunder duress; if the obligor was mentally incompetent, his contract is void;or if a person’s debt arises from anillegal gambling transaction, it is notenforceable). Fraud that induced the obligor to signthe instrument without knowing whatthe instrument was. Discharge of the obligor in insolvencyproceedings (typically bankruptcy).These “real defenses” are set forthin §3-305(a)(1). Several other defensesto payment — the so-called “personaldefenses” — can typically be raised byobligors, including: Nonissuance of the instrument, conditional issuance, and issuance for aspecial purpose. Failure to countersign a traveler’scheck. Modification of the obligation by aseparate agreement. 2018 CUNADEPOSIT ACCOUNT REGULATIONS Payment that violates a restrictiveendorsement. Instruments issued without consideration or for which promisedperformance has not been given. Breach of warranty when a draft isaccepted. Misrepresentation. Mistake in the issuance of theinstrument.This distinction between “real defenses” and all others is important because“real defenses” are effective against allholders — even HIDCs. However “personal” defenses are not effective againstan HIDC. §3-305(c). The essence of theHIDC doctrine is essentially that an honest third party who takes a negotiableinstrument for value generally should notbe made to suffer the same defenses asthe party who negotiated the instrumentto him. The doctrine separates the obligation to pay money from the underlyingtransaction which gave rise to that obligation. If two parties, A and B, have afalling out, the law regards it as unfair todrag third party C into the middle of it.Returning to our example, if Wilsontook the check from Jones: for value;in good faith; without notice that theinstrument was overdue or had beendishonored or that there was an incurreddefault with respect to payment ofanother instrument issued as part ofthe same series; without notice thatthe instrument contained an unauthorized signature or

Bank Collection Code (BCC) of 1928, was adopted by only 18 states. In 1940, the NCCUSL resolved to replace all of its various uniform acts (including the NIL) with a centralized, comprehensive commercial code. The American Legal Institute joined in the effort, and the UCC was born. Article 3, then entitled "Commercial Paper,"

![Solar Code Development v2.5 [Read-Only]](/img/63/solar-20code-20development-20vfinal.jpg)