Transcription

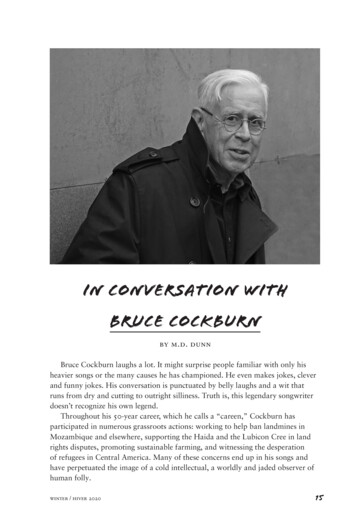

IN CONVERSATION WITHBRUCE COCKBURNBy M.D. DunnBruce Cockburn laughs a lot. It might surprise people familiar with only hisheavier songs or the many causes he has championed. He even makes jokes, cleverand funny jokes. His conversation is punctuated by belly laughs and a wit thatruns from dry and cutting to outright silliness. Truth is, this legendary songwriterdoesn’t recognize his own legend.Throughout his 50-year career, which he calls a “careen,” Cockburn hasparticipated in numerous grassroots actions: working to help ban landmines inMozambique and elsewhere, supporting the Haida and the Lubicon Cree in landrights disputes, promoting sustainable farming, and witnessing the desperationof refugees in Central America. Many of these concerns end up in his songs andhave perpetuated the image of a cold intellectual, a worldly and jaded observer ofhuman folly.WINTER / HIVER 202015

His autobiography, Rumours of Glory (Harper Collins, 2014), is one of themost impressive and articulate musical memoirs in recent memory. While the bookdoes discuss Cockburn’s life, it is more accurately a document of some of the majorconflicts and cultural developments of the late 20th century. Like its author, thememoir looks outward, always working to recognize truth behind appearance.He has also championed literature in an artform that often draws fromhumanity’s baser interests. His lyrics are precise, often narrative in form, sometimesbrutal. Yet, listening closely, there is also humour, faith, and undaunted hope.The song “Maybe the Poet” from the 1984 album Stealing Fire argues for theimportance of poetry, even if it goes unacknowledged by the greater culture. Thesong celebrates the diversity of poets—“male, female, slave, or free, peaceful, ordisorderly”—and documents the dangers of truth-telling: “Shoot him up with lead/ You won’t call back what’s been said / Put him in the ground / But one day you’lllook around / There’ll be a face you don’t know / Voicing thoughts you’ve heardbefore.” The poetic voice will survive, no matter how the domineering forces ofmoney and fashion try to suppress it. Poetry and art, Cockburn seems to be saying,transcend the physical. The voice is larger than the form, and the human need toengage in poetry is unquenchable.Cockburn wrote no songs in the years it took him to complete his memoir.He had stopped thinking of himself as a songwriter when an invitation arrivedto contribute to the soundtrack of Al Purdy Was Here, a documentary aboutthe Roblin Lake poet. The request resulted in “3 Al Purdys,” a song bookendedby two of Purdy’s poems (“Transient” and “In the Beginning Was the Word”)with Cockburn’s eloquent homeless narrator ranting in the middle. Songs startedflowing soon after, resulting in the Juno Award-winning album Bone on Bone(True North Records, 2017). Now, not even two years later, Cockburn has releasedCrowing Ignites, a collection of stunning new instrumentals and his 34th album.This conversation took place on August 14, 2019, with Bruce Cockburn callingin from his home in San Francisco.16contemporary verse 2

THE “I” IN THE SONG/OURGREED-BASED ECONOMYM.D. DUNN: To my count, you have justa few songs from characters’ perspectives: “Call Me Rose,” from SmallSource of Comfort (2011), in whichRichard Nixon is reincarnated as awoman named Rose; “3 Al Purdys,”from Bone on Bone (2017), in whicha homeless man will recite Al Purdypoems for “a 20-dollar bill”; and“Guerilla Betrayed” from Humans(1980) that documents the thoughts ofa desperate soldier.BRUCE COCKBURN: The songs fromGoing Down the Road [a road moviefrom 1970, directed by Donald Shebib]are another example of that, where Ireally went out of my way not to writefrom my own perspective because I hadnever been to Cape Breton at the time. Ihad no idea what it even looked like.MD: Is it liberating to write in a charac-ter’s voice?Japanese industrialists. It’s from thepoint of view of her ex-lover, a guywho got her out of her small town andwhom she later ditches for bigger prospects. And they meet up again. Barneyrecorded it. If it [a fictional narrator]works, it’s a lot of fun.“3 Al Purdys” was like that, once Ithought of the guy. The first thing thatcame was the line: “I’ll give you threeAl Purdys for a twenty-dollar bill.”And I wondered, who would say that?Immediately, this older guy with longwhite hair and a beard, his coattailsflapping in the wind, on the street ranting came to mind. Although he takesexception to the term “ranting” in thesong, but that is basically what he isdoing. He wants everyone to hear AlPurdy’s poetry, and he has his hat out.MD: That song has one of my favouritelines of all time: “They love the littleguy until they get a better offer / withthe dollar getting smaller, they can fitmore in their coffers.” That line encapsulates some of the major problemswith our economy.BC: It worked with “3 Al Purdys.” Iguess I haven’t done enough of it toknow if it can be liberating or not.There is another song I wrote withBarney Bentall called “AtikokanAnnie.” He’d come up with the beginning of the song and kind of a groove.It went: “Annie grew up in Atikokan.Did a lot of drinking. Did a lot ofsmoking.” That is what we startedwith. I took that and constructed astory of a woman who grew up inAtikokan and later gets involved withWINTER / HIVER 2020BC: Yeah. Our economy is greed-based.Of course, it’s going to do what it’sdoing. Unless you have checks andbalances on that greed, and we’re ina place now where people don’t seemto want to limit it. We’re taking ourchances with the rich assholes.That’s also my 7-year-old daughter’sfavourite song on the album becauseof the line, “Porkers in the countinghouse, counting out their bacon.” Sheguffaws every time she hears that line.17

MD: Off that same album, “LookingBC: I’m reading a book called Hitler’sand Waiting” reminds me of Rilke. Idon’t know if I am reading too muchinto it.Priestess by Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke(NYU Press, 2000). It’s the biographyof a woman—and I’m not very farinto it, so I can’t tell you much abouther—named Savitri Devi. She was aFrench-Greek woman who reachedadulthood in the late ’20s/early ’30s.She became an ardent supporter of theAryan myth, in fact is responsible for itto some extent. I don’t know if she wasbrought up as a Christian or not. Shegrows up not appreciating the standardreligions of Europe, and doesn’t likeArabs, doesn’t like Jews, doesn’t likeChristians, and comes to the conclusionthat Hinduism is that last repository ofthe real Aryan mythology, with multiple gods and the culture of belief thatwent with that. In Europe, it had beensuppressed. So, she gets involved increating a campaign to promote Hindunationalism.She goes to India, where she getsthat name. She is an admirer of Hitler,reads Mein Kampf and thinks it’s prettycool, seeing a link between the Nazimythology and her vision of Hindu mythology. After the Second World War,she gets involved with George LincolnRockwell and all the post-war Nazis inAmerica. It seems to suggest that sheis a kind of heroine for the Neo-Nazistoday.BC: Huh. Well, I read Rilke a long timeago. I couldn’t quote any of it at you,but I couldn’t say it’s not an influenceeither. It is a God song. He is a beautiful poet.MD: Do you have a sense of the objec-tive “I” of the poet-speaker in yourmore autobiographical songs? To whatdegree is that really you in the songs?BC: It’s the slightly whitewashed versionof me. It’s the me I am willing to showpeople. It’s generally me. Where there isnot an obvious character, it is me.MD: So, in the song “The Charity ofNight” [from the album The Charity ofNight, 1997) the speaker points a gunat the sexual predator harassing him.Did you have a gun when you trekkedaround Europe as a young man?BC: I’m not sure what I should giveaway here. I want people to keep onthinking.MD: Okay. Moving on.READING ABOUT A NAZI’S MYSTIC /THIS CONVERSATION’S OBLIGATORYTRUMP REFERENCE / THE COMINGMD: Timely. Is the current age living upto the dystopic fiction you’ve read?DISASTERBC: It’s pretty close. Certainly, youMD: What are you reading these days?18can imagine it heading there. It isn’tas dystopic as some of that stuff gets.contemporary verse 2

It’s definitely on a downward slope.Whether we’ll recover in some timelymanner, I don’t know. But it doesn’tlook great.MD: I just read that a few hundredthousand New Yorkers have signed apetition to have Fifth Avenue, where theTrump Tower is, renamed after Obama.BC: That is really good! It’s so petty, buteverything is so petty right now.MD: Who knew Donald Trump wassuch as asshole, except anyone who hasbeen paying attention since the 1980s?North America bring people together ormake them crazier.BC: It’s hard to say. People will becomemore desperate than they are now.Think of the gap between the Northand the South, which has never recovered from the Civil War, that gap isbecoming evident as the current eventsunfold. And as the South heats up,physically, it’s going to become moredifficult for people to live there.WHERE IS HERE? / THE POWEROF PLACEMD: You have a practice of document-BC: Well, yeah. How could they havethought otherwise? How can they stillthink otherwise? It’s just astounding tome. The people he clearly does not loveor care for at all admire him so much,and of course he basks in the glory.That part he cares about.Bigger than that is the way in whichhis policies and pronouncements havemetastasized into the whole culture ofthe United States. It’s now a culture ofanger and hostility. Those sentimentswere never not there but it wasn’tdominant in my lifetime. Even in theVietnam era, where it got very livid, itstill wasn’t where it’s at now. It’s in allthe structures: the court system, the environmental concern. He’s done a goodjob of infecting everything. How we canever recover from that, I don’t know.MD: It’s going to be fascinating andterrifying to see if the environmentalpressures we are about to experience inWINTER / HIVER 2020ing in album liner notes where a songwas written: Is that where you werewhen you wrote the lyric or where itcame together as a song?BC: It’s where the lyrics are first born.Sometimes, it’s the idea and the lyricsget worked on later. It might be partlywritten in the first place and then getamended or added to later. But, yes, it’sabout the lyrics.MD: Do you believe in Sacred Places,genius loci; that some places are morepowerful?BC: Not sure I would use the word“sacred,” but there certainly are placeswhere the spirit, or a spirit, seem to bepresent. And I’ve been a few places likethat in my life. There is this notion of“spirit of place.”When I was in Mali [for the documentary River of Sand (1997)], the19

village we filmed in had a spring, whichwas rare in that part of the world. As aresult, they were able to do better thanany of their neighbouring communities.The spring had a spirit attached to it.The Dogon people I met were predominantly Islamic in belief. I asked thechief, who was very welcoming to us,about the spirit of the spring. He said,“Oh, yeah. We used to sacrifice a blackgoat to it every year. But now we havethe faith, and we don’t do that anymore. We just sacrifice a chicken.”the Nazis, it was something even deeper.I don’t know, other people would go tothe same place and feel nothing. So, it’sa subjective take on it.MD: The spirit’s cutting down on redMD: You’ve said that most of your lyricsmeat, I guess.are written separately from the musicand later almost scored like a film withthe guitar. Do you have a sense of thesecomponents happening simultaneouslyand subconsciously? Like the lyricsyou’ve written match a guitar pieceyou’ve been working on?BC: It was cute, but the spring had areal presence about it. Almost like, Ihate to use this example, but it is what’scoming to mind. It was almost like aLord of the Rings kind of a thing. Imean, not like it felt like being in theLord of the Rings type of thing, but thesense of a presence attached to a placecould have been written about in Lordof the Rings. I remember being up inthe Yukon and standing near a waterfallthat had a presence about it. I’ve beenin forests that felt like that too. Likesome semi-conscious, at least, somekind of a consciousness that notices theintruder or the bystander, and you feelthat. People talk about power placeslike Machu Picchu and the pyramidsand all that, but I don’t have much of asense of it.I was at a Nazi monument inGermany that was the worst place Ihave ever been. It just felt utterly evil.And it wasn’t only the association with20MD: There must be a reason thatchurches are built over temples andtemples built over groves.BC: There are a lot of churches in mallsnow. I don’t know what that means.ON WRITINGBC: It’s not likely to be a fully devel-oped piece, but it does happen. WhenI am writing lyrics, I generally have arhythm in mind to hang the words on.It doesn’t generally end up being therhythm of the song, but there is a senseof it. Sometimes it happens that thereis a guitar riff that has been waiting forlyrics and can become the basis of asong.MD: You’ve said that you don’t write ev-ery day but wait for the lyrics to come.As a creative writing teacher, I hate tohear this practice being so successful.BC: There is a good argument for exer-cising the muscles. I tried writing dailycontemporary verse 2

for a year, and I gave it up. I wouldn’trecommend waiting to everyone. I thinkyou can develop the flow of ideas byusing your brain and translating it intothe physical by writing it down, or typing it. I used to find, too, that typing—Iam not a typist, I have no typing skillswhatsoever, I’m a hunt-and-peck, twoindex fingers type of guy—but used tofind that typing brought out a wholedifferent set of ideas than writing witha pen.BC: Yeah. Her stuff from the ’70s is sovisceral and intense. She has a memoirout now about that period, I have it buthaven’t got to it yet. I heard her interviewed on NPR and went out and gotit. Those poems jump off the page. Herlater stuff is a bit more difficult, I find.It’s heavy poetry.MD: Did her book about El Salvador,The Country Between Us (HarperPerennial, 1982) inform your work inCentral America?MD: Some novelists will use typewritersfor dialogue and longhand for narrativeor descriptive passages.BC: Interesting. Manual typewriters areharder on the fingers, and harder onthe fingernails if you’re a guitar player,but more satisfying than the computerkeyboard. I don’t know if it is a kindof conceit, but the retro aspect and thephysicality of the manual typewriter isappealing to me. I have an old typewriter, an old portable. I haven’t used it in awhile, but I used to type letters on it.INFLUENCES/ART AND POLITICS/THEGOOD AND THE DRIVELMD: When we spoke a couple of yearsago, you identified Carolyn Forché asa poet whose work you’ve admired. Iwasn’t familiar with her then but nowsee some interesting parallels betweensome of her writing and some of yours,thematically and as a response to injustice. You both often adopt the stance ofthe artist as witness and documentarian.WINTER / HIVER 2020BC: Sure it did. Absolutely. Not surewhat happened in what order, but thatbook was one of the things my brotherdirected me to.My brother Don was involved withsolidarity work with the Salvadoranrebel movement, and he kept feeding me stuff about Nicaragua and ElSalvador including poems by ErnestoCardenal and Carolyn Forché, especially The Country Between Us.I think I had read some of both ofthose poets before I actually went toCentral America for the first time. Withreference to my songs about CentralAmerica, before Stealing Fire (1984), onThe Trouble With Normal (1983) thereis a song called “Tropic Moon” thatwas definitely influenced by CarolynForché. The songs I wrote on StealingFire owe more to Ernesto Cardenalthan to Forché because I was steepedin Nicaragua. Two of his earlier bookscontain more of what he describes asdocumentary poems. That approach ofwriting was on my mind during StealingFire.21

When I think of Carolyn Forché, Ithat poetry addressed events and thethink of Allen Ginsburg too. More ofspirit of people. You could see that, itthe late ’60s and ’70s Ginsburg, likewas so graphic. I was already on myThe Fall of America and that period.way of losing the bias I had grownIt’s also documentary, a different styleup with, the idea that art should beand way of using language, but aseparate from poetry, but Chile reallysimilar spirit: this is what happened,clinched it. In Nicaragua, Somozathis is what I see. And it’s very concrete. jailed the poets. And so many poetsThose three poets figure prominentlysupported the revolution. All throughin my understanding ofLatin America, there iswriting.I was alreadyno distinction like thatVictorian distinction I’don my way ofMD: You have said yougrown up with. It waslosing the bias perfectly fine for poems towere taught that artand politics should beI had grown up be about what we wouldseparate concerns andcall political topics.with, the idea What it comes down tothat you struggled tobring the political intothat art should is trying to talk truth toyour art. Did thesepeople, which is some ofbe separate from what poetry is supposedwriters help with thatprocess?poetry, but Chile to do. You can’t avoidthe political becausereallyclinchedBC: I think they did,it’s part of life. You putactually. It was partit. In Nicaragua, people together, andof a process. It wasn’tyou have politics. EvenSomoza jailed if the people gatheredentirely down to them.A big part of thatthe poets. And are only the very limiteddevelopment cameof a particularso many poets readershipabout when I went topoet, there is still aChile, the same yearsupported the political element there.I went to Nicaraguarevolution.for the first time, andMD: These concerns seemPinochet’s dictatorshipto come together in yourwas thriving. There was all this poeticsong “Gavin’s Woodpile” from theenergy, which the fascist authoritiesalbum In the Falling Dark (1976). Likewere going well out of their way tothe spiritual elements of your work,suppress. Like they suppressed Neruda.and concerns for social justice and theWell, they may have poisoned him. It’senvironment all came together in thatnot clear how he died. There’s somesong.mystery surrounding his death. But theyunderstood that poetry was a threat,22contemporary verse 2

BC: The political is the last thing tocome together in the grouping of thatthematic material. Once you startthinking about social justice, or theenvironment, you immediately come upagainst the political because you can’tchange anything otherwise. You can’teven get people to talk about it withoutgetting involved with the politicalworld. Even if it is only just to get awhole bunch of people to talk and thendrawing heat from the political powersthat be, you’re going to be confrontedwith it at some point. It’s especiallytrue if you’re trying to do anythingconcrete like address an environmentalissue where there are economic interestsinvolved, which there always are. Theeconomic interests are in conflict withthe environment, then you are suddenlyin the realm of politics.MD: You have said that your goal is towrite a good song, not to champion acause. How do you know if it’s a goodsong? Have you ever written, or do youstill write, bad songs?baseline, everything else looks prettygood.MD: As you become more experienced,do you find the things you write aremore useable now, that you don’t haveto work through so much bad stuff?BC: I weed it as I go. That is partlybecause I have already said quite a lotand feel pretty much the same aboutthings. There’s no point in repeating it,unless you can think of something newto bring to a concept, or you have sometwist in the writing that is new. There isno point in just going over the same oldground. It’s harder to find new thingsto write about, or new ways of writingabout the old things. Because I’ve doneso much, it takes longer to come upwith ideas that are useable. And I amfussier now. I don’t think I have evermade an album of perfect songs. I amnot sure if I have ever made a perfectsong.MD: Some would disagree with you, Mr.Cockburn.BC: There are songs that live on thebottom shelf in the storehouse of mybrain that don’t get looked at too oftenbecause I don’t feel too excited by them,but when I am forced to hear them Iusually realize that they aren’t that bad.There might be an embarrassing linehere or there—in fact, there definitelyare—but sometimes the lyrics are okaybut the music doesn’t work as well.The stuff I wrote in the ’60s, when Iwas just starting to write songs, I meanI wrote a lot of drivel. So, if that is theWINTER / HIVER 2020BC: They are welcome to. The more thebetter.INTERPRETATIONSMD: You’ve said that a fan once scoldedyou for the song “Pacing the Cage,”saying it sounds like a suicide note.Are you often surprised by how peopleinterpret your songs and the way yoursongs have functioned in their lives?23

BC: The first time I became aware ofthat was with a song called “Dialoguewith the Devil” [from the albumSunwheel Dance, 1972] when a journalist said it was about reconciling thedevil within us. And I was horrified.Because the devil in that song is a jerk.Get him away! It’s a reflection of allthe bullshit: money and fame and theseduction of the devil. I was associatingthe devil with the biblical image, but it’snot even biblical, it’s John Milton, thatversion of the devil. For that journalistit meant something different. But thathappens across the board. You writesomething and you put it out there, andI know what I mean by it. Once in awhile, I get an indication that someonegot what I thought I was putting into it.But you can never assume that. Peopleperceive everything through their ownfilters. You have no control over that.The best you can do is to try to be asclear as possible with what you aresaying.MD: Does doubt play a role in faith?BC: It does for me. Not by design. It isstimulated by ideas and cogent observations by people who don’t share thesame faith. If someone asks a goodquestion, I can’t ignore it. You can’tjust write it off. A lot of people havethought deeply about faith and theirquestions can incite doubt.Apollinaire’s poem “Victoire.” Doyou read in any languages, other thanFrench and English?BC: No. I can hack my way throughSpanish, but I need the bilingual editions. Then, I check the “translation”with a dictionary. Some languagesseem to flow into English without impediment. Other languages don’t. LikeRussian, I have only found one reallygood translation of a Russian writer,Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita.Even Yevtushenko’s poetry for instance,and he’s a contemporary with the Beatgeneration, has such laboured sounding and dry translations in English. Hecouldn’t have become an importantpoet and be like that in his originallanguage. The translations are helpfulto know what he’s saying, but it justdoesn’t work.On the other hand, Japanese poetryfrom almost any era in translation flowsreally well in English. If you’re familiarwith a language, as I am with French tosome degree, you can see how literal thetranslation is. And, if it isn’t literal, is itreally saying what the poet was saying?Apollinaire’s stuff uses French grammaratypically, but less so than someone likeBlaise Cendrar, who was Apollinaire’sdirect descendant in a way. I find ithelpful to translate.MD: How does it benefit a writer to readin a variety of languages?LANGUAGESBC: I just like to know what they areMD: “Mon Chemin” from Bone onBone was inspired by Guillaume24really saying if I like the poem. Youread the translations, and it’s okay. Icontemporary verse 2

don’t remember the English translationof the Apollinaire poem, but the twolines in English are “Who knows wheremy road would be?” The lines hit me,and I knew I could make a song fromthat. It had been a long time since I’dwritten a French song. I wasn’t sure itworked, but we got a good response inQuebec from that song. So, I guess itdidn’t suck.MEETING THE SHAMAN KING ANDDANCING IN THE DRAGON’S JAWSMD: In your song “Mystery” from thealbum Life Short Call Now (2006) yousing about seeing “star-strewn space”in the shaman’s eyes and in Rumoursof Glory you reveal that NorvalMorrisseau was the shaman. What wasit like to hang out with him?BC: I didn’t hang out with him for long,and it was only once. He was veryinteresting, I thought. He had a big ego,but he also was gracious and kind ofintentionally mysterious. But he wasexactly that, he was shamanic. It wasreally clear. The painting we used on theDancing in the Dragon’s Jaws albumrepresented something he’d experiencedin the astral plane, according to him.Those little figures on the back of thedragon, or whatever it is, are humanspirits travelling in the astral plane.He was staying at a furnishedhigh-rise in Cabbage Town in Toronto.Bernie [Finkelstein, Cockburn’s longtime manager] had made contact withMorrisseau’s dealer. He was expecting us. We knocked on the door, andWINTER / HIVER 2020a young Native guy invited us in andsaid Norval was meditating in the backbedroom. We waited for him in the living room for some time. The apartmentwas a short-term rental, like an Airbnb.It was pretty sterile except in one cornerthere was a tree stump with a collectionof lichen and moss burning on it, producing clouds of acrid smoke. This wasbefore there were smoke detectors, soyou could do this kind of thing. It functioned as incense, and it was a pleasantenough smell, but it was heavy smoke.We sat in that for a while. It wasn’t adrug of any sort. After about twentyminutes, he greeted us and offered ustea. As he handed me a cup, he said, “Itis the King who serves.” With a twinklein his eye. When we made eye contact,it was just like I describe in the song.Instead of his eyes, there were windowsinto intergalactic space. It was spooky.A really dislocating kind of moment.It was over very quickly. He saw mesee that, and his grin changed to one ofacknowledgement, like: “Yeah. That’swhat’s going on here.”MD: We have the album jacket ofDancing in the Dragon’s Jaws framedon our kitchen wall, partially becauseyou signed it, but also because the image is so striking.BC: Bernie has the original. That waspart of the deal. Buy the painting andyou can use it on your album cover.MD: Maybe you’ve noticed this, butwhen you look at it from the side it appears to be three dimensional the way25

the three panels of colour strobe againsteach other.three separate panels. That is interesting. I guess I haven’t looked at itenough to respond to that. But it is anincredible painting. We were calling thealbum Dancing in the Dragon’s Jawsand there was this painting that seemedlike a match made in heaven.you’re mostly looking at a black, emptyspace with voices and human sounds,and the sense of a presence, becauseyou can feel the audience there, but youcan’t really see them. Sometimes peoplewant to talk too long, but more oftenthey just say whatever’s on their minds,and it’s quite interesting to hear it. Ireally enjoy meeting people. It does gettiring. I do feel that the show was whatit was really all about.MD: An incredible painting for an in-MD: People must lay heavy stuff on you?BC: It was a triptych. So, it really iscredible album, that’s for sure.MEET & GREET, BUT PLEASE STOPGIVING HIM STUFFMD: We are getting close to the end. Ihope I’m not taking up too much ofyour time.BC: No. It’s okay.MD: It’s very impressive that you stilldo a meet and greet after shows. Manypeople in your position would just siton the bus while the crew packs up,saying, “The show is enough.” You’restill open like that. What do you getfrom it?BC: I didn’t do it for many years. Andlong after it became a trend for musicians to do that, because it encouragesaudiences to buy merchandise, I stilldidn’t do it. Everybody was doing it,and I wasn’t because it just seemed likea horrible idea. But I finally thought Iwould try it to see what I thought, and Ireally enjoyed it because I get to see thepeople. If you’re looking at an audience,26BC: People give me lots of stuff. Andwhat can I do with it all? Sometimes Ican’t even get them home, if it’s a pieceof art or something. It’s not going tosurvive being on the plane, or on thetour bus. That part gets uncomfortable.Lots of books, and books are heavy.You end up with a box of books andhave to pay extra to get them home.NO BEATS/NO BOOKMD: Are there any remnants of the Beatpoets in present-day San Francisco?BC: Oh, there is a kind of tourist pres-ence. I don’t know if any of the youngtech generation who is sort of in chargehere now is aware of any of that. Idon’t know that most of them read. It’llcome back around. Maybe they willwrite poetry in emojis.MD: Do you see young people makingnew art in San Francisco?BC: No. I don’t. I’m not sure they arenot here, but I don’t know how theycontemporary verse 2

could afford to be here. What I witnessed was them all leaving. The artscene that was evident even ten yearsago, when I first got here, is gone. Thereis certainly an art scene here though.The symphony is a good one. On theestablished, professional level there isa scene. There are good jazz playersand good opera and that stuff. But forpeople up and coming in the pop scene,I don’t know who is out there. Peoplemake albums in their bedrooms, andthey circulate them online. I don’t lookthere, so I don’t know. There are fewvenues. The famous old ones are goingbit by bit. It’s hard to say how anyonegets started with nowhere to play.Blomer’s environmental anthologyRefugium: Poems for the Pacific (CaitlinPress, 2017) and which you later turnedinto a song for the Bone on Bonealbum. Was this your first publishedpoem?MD: That’s cyclical too, I guess.BC: I have not. It’s questionable to meBC: For sure. When the shit hits the fan,and there is no electricity, there will belots of live music.MD: “False River” is a poem you wrotefor Victoria poet laureate YvonneWINTER / HIVER 2020BC: No. There was a little magazinecalled Weed (1966-67, edite

reads Mein Kampf and thinks it's pretty cool, seeing a link between the Nazi mythology and her vision of Hindu my-thology. After the Second World War, she gets involved with George Lincoln Rockwell and all the post-war Nazis in America. It seems to suggest that she is a kind of heroine for the Neo-Nazis today. MD: Timely. Is the current age .