Transcription

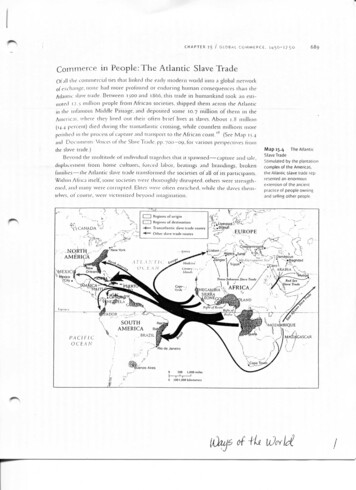

CHAPTER. 1 /689GLOBAL COMMERCE.Commerce in People: The Atlantic Slave TradeOf .ill [lit? commercial ties that linked the early modern world into a global networkof excli.inge, none had more profound or enduring human consequences than theAtlantic slave trade. Between isoo and 1866. this trade in humankind took an estimated I 2 . S million people from African societies, shipped them across the Atlanticin the infamous Middle Passage, and deposited some 10.7 million of them in theAnuTic.is. where they lived out their otten brief lives as slaves. About i.S million( 1 4 . 4 percent) died during the transatlantic crossing, while countless millions moreperished in the process ol capture and transport to the African coast. 1 ' (See Map i s . 4and Documents: Voices ot the Slave Trade, pp. 700-09. tor various perspectives tromthe slave trade.)Beyond the multitude ot individual tragedies that it spawned—capture and sale,displacement from home cultures, forced labor, beatings and brandings, brokenfamilies — the Atlantic slave trade transformed the societies of all of its participants.Within A f r i c a itself,some societies were thoroughly disrupted, others were strengthened, and many were corrupted. Elites were otten enriched, while the slaves themselves, ot course, were victimized beyond imagination.II Regions of originII Regions of destination. -*'Transatlantic slave t r a d e routes-Other slitve trade routes: -NORTH,AMERICA"r.Jangrer\\- ' i- T- .-*;'.EUROPE *.fclc,l!iiiriincnii .S,-,iI/T .- '" ».' ""«—.\ //vjTrnitf-Salmran SI arc Trade /V-SOUTHAMERICABFL ZILMap 15.4The AtlanticSlave TradeStimulated by the plantationcomplex of the Americas,the Atlantic slave trade represented an enormousextension of the ancientpractice of people owningand selling other people' \B' .\T

**""1In tliL Rericas, the slave trade added a substantial African presence to the mixot European and Native American peoples.This African diaspora (the transatlanticspread of African peoples) injected into these new societies issues of race that endurestill in the twenty-first century. It also introduced elements of African culture, suchas religious ideas, musical and artistic traditions, and cuisine, into the making ofAmerican cultures. The profits from the slave trade and the forced labor of Africanslaves certainly enriched European and Euro-American societies, even as the practiceof slavery contributed much to the racial thinking of European peoples. Finally, slavery became a metaphor for many kinds of social oppression, quite different fromplantation slavery, in the centuries that followed. Workers protested the slavery of wagelabor, colonized people rejected the slavery of imperial domination, and feministssometimes defined patriarchy as a form of slavery.The Slave Trade in ContextThe Adantic slave trade and slavery in the Americas represented the most recent largescale expression of an almost universal human practice — the owning and exchange ofhuman beings. With origins in the earliest civilizations, slavery was widely acceptedj as a perfectly normal h u m a n enterprise and was closely linked to warfare and capture. Before r soo, the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean basins were the major arenasot the Old World slave trade, and southern Russia was a major source ot slaves. ManyAfrican societies likewise both practiced slavery themselves and sold slaves into theseinternational commercial networks. A trans-Saharan slave trade had long funneledAfrican captives into Mediterranean slavery, and an East African slave trade broughtAfricans into the Middle East and the Indian Ocean basin. Both operated largelywithin the Islamic world.Furthermore, slavery came in many forms. Although slaves were everywherevulnerable "outsiders" to their masters' societies, in many places they could beassimilated into their owners' households, lineages, or communities. In some places,children inherited the slave status ot their parents; elsewhere those children werefree persons. Within the Islamic world, the preference was for female slaves by a twoto-one margin, while the later Atlantic slave trade favored males by a similar margin.Not all slaves, however, occupied degraded positions. Some in the Islamic worldacquired prominent military or political status. Most slaves in the premodern worldworked in their owners' households, farms, or shops, with smaller numbers laboringin large-scale agricultural or industrial enterprises.The slavery that emerged in the Americas was distinctive in several ways. One wassimply the immense size of the traffic in slaves and its centrality to the economies ofcolonial America. F u r t h e r m o r e , this New World slavery was largely based on plantation agriculture and treated slaves as a f o r m ot dehumanized property, lackung anyrights in the society of their owners. Slave status throughout the Americas was inherited across generations, and there was little hope of eventual freedom for the vastmajority. Nowhere else, with the possible exception of ancient Greece, was widespreadslavery associated with societies affirming values of human freedom and equality.iVrhaps most distinctive \v;is the racial dimension: Atlantic slaw. --'came to be i d e n t i fied whol'v with Afriir.i and w i t h "blackness. How did t h i s exceptional form ol'slav The o r i g i n s of Atlantic slavery clearly l i e HI Hit Mediterranean world ,md \ v i t hi l i . u in.i\n sweetener known as sugar. Until the Crusades. Europeans k n e wn o t h i n g ot sugar and relied on honey and I r m t s tu sweeten t h e i r b l a n d die is. H o w ever, .is t h e y l e a r n e d from the Arabs a b o u t s u g a r c a n e and the l a b o r i o u s t e c h n i q u e sfor prod IK. in» usable sugar. Europeans established sugar-producing plantations w i t h i ntin- 1 M e d i t e r r a n e a n a n d later o n v a r i o u s islands l t t h e coast ofWest A f r i c a . I t w a s a"modern industry, perhaps the f i r s t one. in thai u required huge capital investment.substantial technology, an almost factory-like discipline among workers, and a massmarket of consumers. The immense difficulty and danger of the work, the limitationsattached to seil labor, and the general absence of waye workers all pointed 10 slaveryas ,1 source ot labor lor sugar plantations.Initially, Slavic-speaking peoples from the Black Sea region l u r n i s h e i l the b u l k o(the slaves for Mediterranean p l a n t a t i o n s , so m u c h so t h a t "Slav" became the basis lorthe word "slave" in m a n y European languages. I n I 4 S 1 . however, w h e n the )i t o m a nTurks seized Constantinople, the supply ol Slavic slaves was effectively cm off At t h esame time. Portuguese m a r i n e r s were exploring the coast ofWest A f r i c a ; they were l o o k i n gp r i m a r i l y for gold, b u t they also f o u n d there.in a l t e r n a t i v e source of slaves available for sale.Thus, when sugar, and later tobacco and cotton. p l a n t a t i o n s took hold in the A m e r i c a s .Europeans hod already established l i n k s to aWest A f r i c a n source of supply.Largely through a process ol e l i m i n a t i o n .A f r i c a became the p r i m a r v source ot slavelabor tor tlie p l a n t a t i o n economies ol theAmericas. Slavic peoples were no longeravailable; Native A m e r i c a n s quickly perishedfrom European diseases: marginal Europeanswere Christinns and therefore supposedlyexempt from slavery; and European indentured servants were expensive and temporary.Africans, on the other hand, were skilled farmers; they had some i m m u n i t y to both tropicaland European diseases; they were not Chrisn a n s : t h e y were, r e l a t i v e l y s p e a k i n g , close athand: and they were readily available in substantial numbers through African-operatedcommercial networks.Moreover, Africans were black. The preciserelationship between slavery and European/n

racism has long been n much-debated subject. Historian David Brion Davis has suggested the controversial view that "racial stereotypes were transmitted, along withblack slavery itself, from Muslims to Christians." i y For many centuries, Muslims haddrawn on sub-Saharan Africa as one source of slaves and in the process had developeda tonn ot racism. The fourteenth-century Tunisian scholar Ibn K h a l d u n wrote thatblack people were "submissive to slavery, because Negroes have little that is essentiallyon the back, and seizing him, disarmed h i m together with the rest of his attendance. Limong which was Benedict Stafford, commander of the Mfiyiin-t. (whomade hi? escape and ran like ;i lusty fellow to his ship) ;md several cithers, whotogether with the agent were taken and put i n t o the kind's pound and stayedthere three or four days till t h e i r ransom was brought, v a l u e five hundred bars."' 1human and have a t t r i b u t e s that are quite similar to those of d u m b animals." 2 0Other scholars find the origins of racism within European culture itself. For theEnglish, argues historian Audrey Smedley, the process ot conquering Ireland had generated by the sixteenth century a view of the Irish as "rude, beastly, ignorant, cruel,and u n r u l y infidels," perceptions that were then transferred to Africans enslaved onEnglish sugar plantations of the West Indies."' Whether Europeans borrowed suchimages of Africans from t h e i r Muslim neighbors or developed them independently,slavery and racism soon went hand in hand. "Europeans were better able to toleratet h e i r brutal exploitation of Africans," writes a prominent world h i s t o r i a n , " b y imagi n i n g that these Africans were an i n f e r i o r race, or b e t t e r s t i l l , not even human."""In exchange for slaves. A f r i c a n sellers sought both European and I n d i a n textiles,cowrie shells (widely used as money in West A f r i c a ) , European m e t a l goods, f i r e a r m sand gunpowder, tobacco and alcohol, and v a r i o u s decorative items such as beads.Europeans purchased some of these items — cowrie shells and I n d i a n textiles, forexample-—with silver m i n e d in the A m e r i c a s . T h u s the slave trade connected w i t hcommerce in silver and textiles as it became part of an emerging worldwide networkof exchange. Issues about the precise mix ot goods A f r i c a n a u t h o r i t i e s desired, aboutthe number mid quality of slaves to be purchased, and always about the price of everyt h i n g were settled in endless n e g o t i a t i o n (see D o c u m e n t i s . 2 , pp. 703-05). In mostplaces most of the time, a l e a d i n g s c h o l a r c o n c l u d e d , the slave trade took place "notu n l i k e international trade anywhere m the world ol r h e period.""If African a u t h o r i t i e s and e l i t e classes m m a n y places controlled t h e i r side ofthe slave trade, on occasion they were almost overwhelmed by it. Many small-scalekinship-based societies, lacking the protection of a strong state, were thoroughly disrupted by raids from more powerful neighbors. Even some sizable states were destabilized. In the early s i x t e e n t h c e n t u r y , the kingdom of Kongo, located mostly inpresent-day Angola, was badly damaged by the commerce in slaves and the a u t h o r in,.' of its ruler severely undermined (see Document i s . 3 , pp. 705-07).Whatever the relationship between European buyers and A f r i c a n sellers, for theslaves themselves—who were seized in the interior,often sold several times on the harrowing journey to the coast, sometimes branded, and held in squalid slave dungeonswhile awaiting transportation to the New World — it was a n y t h i n g but a normal commercial transaction (see Document 15.1, pp. 700-03). One European engaged in thetrade noted that "the negroes are so wijjful and loath to leave their own country, thatthey have often leap'd out ot the canoes, boat, and ship, into the sea, and kept underwater till they were drowned, to avoid being taken up and saved by our boats.""-"Over the four c e n t u r i e s of the slave trade, millions of A f r i c a n s underwent somesuch experience, but their numbers varied considerably over time. During the sixteenth century, slave exports from Africa averaged u n d e r 3,000 annually. In thoseyears, the Portuguese were at least as much interested in African gold, spices, andtextiles. Furthermore, as in Asia, they became involved in transporting Africangoods, i n c l u d i n g slaves, from one A f r i c a n port to a n o t h e r , thus beconiing the "truckdrivers"of coastal West A f r i c a n commerce."' In the seventeenth century, the pacepicked up as the slave trade became highly competitive, with the British, Dutch, andFrench contesting the earlier Portuguese monopoly.The century and a half between1700 and iSso marked the h i g h p o i n t of the slave trade as the pla 1 \on economiesof the Americas boomed (see the Snapshot on p. fi ;4).The Slave Trade in PracticeThe European demand for slaves was clearly the chief cause of this tragic commerce,and from the point of sale on the African coast to the massive use of slave labor onAmerican plantations, the entire enterprise was in European hands. Within Africaitself, however, a different picture emerges, for over the four centuries of the Atlanticslave trade, European demand elicited an African supply. A few early efforts by thePortuguese at slave raiding along the West African coast convinced Europeans thatsuch efforts were unnecessary and unwise, for African societies were quite capableot defending themselves against European intrusion, and many were willing to selltheir slaves peacefully. Furthermore, Europeans died like flies when they entered theinterior because they lacked immunities to common tropical diseases.Thus the slavetrade quickly came to operate largely with Europeans waiting on the coast, eitheron their ships or in fortified settlements, to purchase slaves from African merchantsand political elites. Certainly Europeans tried to

Atlantic slave trade. Between isoo and 1866. this trade in humankind took an esti-mated I2.S million people from African societies, shipped them across the Atlantic in the infamous Middle Passage, and deposited some 10.7 million of them in the AnuTic.is. where they