Transcription

with respect to sex

Worlds of Desire: The Chicago Series on Sexuality, Gender, and CultureEdited by Gilbert Herdtalso in the series:American Gayby Stephen O. MurrayNo Place Like Home: Relationships andFamily Life among Lesbians and Gay Menby Christopher CarringtonOut in Force: Sexual Orientation andthe Militaryedited by Gregory M. Herek,Jared B. Jobe, and Ralph M. CarneyBeyond Carnival: Male Homosexualityin Twentieth-Century Brazilby James N. GreenQueer Forsteredited by Robert K. Martin andGeorge PiggfordThe Cassowary’s Revenge:The Life and Death of Masculinityin a New Guinea Societyby Donald TuzinMema’s House, Mexico City:On Transvestites, Queens, and Machosby Annick PrieurTravesti: Sex, Gender, and Culture amongBrazilian Transgendered Prostitutesby Don KulickSambia Sexual Culture:Essays from the Fieldby Gilbert HerdtGay Men’s Friendships:Invincible Communitiesby Peter M. NardiA Plague of Paradoxes: AIDS, Culture,and Demography in Northern Tanzaniaby Philip W. SetelThe Course of Gay and Lesbian Lives:Social and Psychoanalytic Perspectivesby Bertram J. Cohler andRobert M. Galatzer-LevyHomosexualitiesby Stephen O. MurrayThe Bedtrick: Tales of Sex and Masqueradeby Wendy DonigerMoney, Myths, and Change: The EconomicLives of Lesbians and Gay Menby M. V. Lee BadgettThe Night Is Young: Sexuality in Mexicoin the Time of AIDSby Héctor CarrilloThe Emerging Lesbian: Female Same-SexDesire in Modern Chinaby Tze-lan D. SangCoyote Nation: Sexuality, Race, and Conquestin Modernizing New Mexico, 1880–1920by Pablo Mitchell

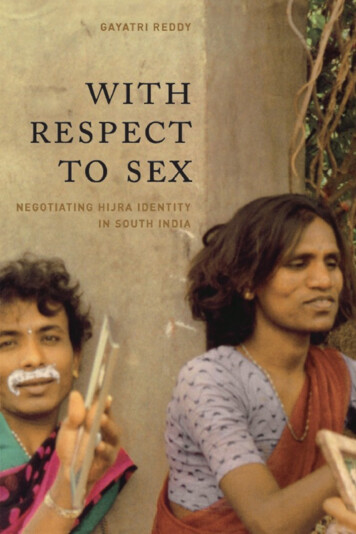

With Respect to Sexnegotiating hijra identity in south indiaGa yatri ReddyThe University of Chicago Press / Chicago and London

Gayatri Reddy is assistant professor of anthropology and gender and women’s studies at theUniversity of Illinois at Chicago.The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London C 2005 by The University of ChicagoAll rights reserved. Published 2005Printed in the United States of America14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 051 2 3 4 5isbn: 0-226-70755-5 (cloth)isbn: 0-226-70756-3 (paper)Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataReddy, Gayatri.With respect to sex : negotiating hijra identity in South India / Gayatri Reddy.p. cm. — (Worlds of desire)Includes bibliographical references and index.isbn 0-226-70755-5 (cloth : alk. paper) — isbn 0-226-70756-3 (pbk. : alk. paper)1. Transsexuals—India, South. 2. Transsexualism—Religious aspects—Islam. 3. Sex role—India,South. 4. Sex differences—India, South. 5. Sex role—Religious aspects—Islam. 6. Gender identity—India, South. 7. Islam and culture—India, South. 8. Transvestism—Religious aspects—Islam.9. Prostitution—India, South. 10. Hyderabad (India)—Social life and customs. 11. Secunderabad(India)—Social life and customs. I. Title. II. Series.HQ77.95.I4R43 2005305.3 0954—dc222004015754 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed LibraryMaterials, ansi z39.48-1992.

in gratitudeTo the memory of my mother, who taught me to love booksand encouraged my curiosity early in life

contentsAcknowledgments / ixNote on Transliteration / xiii1The Ethnographic Setting2Hijras, Individuality, and Izzat173Cartographies of Sex/Gender444Sacred Legitimization, Corporeal Practice: HinduIconography and Hijra Renunciation78“We Are All Musalmans Now”: Religious Practice,Positionality, and Hijra/Muslim Identification996(Per)Formative Selves: The Production of Gender1217“Our People”: Kinship, Marriage, and the Family1428Shifting Contexts, Fluid Identities1869Crossing “Lines” of Subjectivity: TransnationalMovements and Gay Identifications211510 ConclusionAppendix / 233Notes / 235Glossary / 2651223References / 273Index / 299

acknowledgmentsMy first and greatest debt is to my hijra and koti friends and acquaintancesin Hyderabad for welcoming me so openly into their lives. If it weren’t fortheir hospitality, generosity, and warmth, not only would this book havebeen impossible to write, fieldwork would not have been the joy and pleasure that it was. I would especially like to thank those hijras and kotis I havereferred to in this book as Munira, Surekha, Saroja, Irfan nayak and Amirnayak, Frank, Shanti, Rajeshwari, Aliya, Srilakshmi, and Nagalakshmi (allpseudonyms) for their unstinting gifts of time, patience, energy, hospitality,and friendship. I remain forever in your debt.Research for this book was made possible by generous grants and fellowships from the National Science Foundation, the Association for Womenin Science, the Mellon Foundation, and Emory University. I would alsolike to express my gratitude to the Sexuality Research Fellowship Program(SRFP) of the Social Science Research Foundation and its director, Diane diMauro. Although research for this particular project was not funded by theSRFP, their subsequent support, both material and intellectual, in the formof a generous postdoctoral award and the fellowship of brilliant sexualityresearchers, was crucial for my ability to clarify my analysis and crystallizemy writing in the final stages of this project.As in the case of all collective enterprises, this book could not have beenwritten without the support and encouragement of many individuals andinstitutions. At Columbia University, where I began my graduate work, Iam extremely grateful and will remain forever indebted to Joan Vincentand Carole Vance for their support and generous encouragement, as well astheir warmth and understanding in those early years of my career.At Emory University I would first like to thank the members of mydissertation committee, all of whom were incredibly supportive and instrumental in creating the intellectual and social environment that allowed me

x / Acknowledgmentsto complete this project. I am truly grateful and honored to have had the opportunity to work with all of you. Don Donham initially encouraged me toremain in academia and, through his insightful comments and suggestionsand generous validation of my work, was also largely responsible for mygrowth as an intellectual over these many years. Joyce Flueckiger offeredinvaluable suggestions and insights on South Asian anthropology, religion,and ethnography, and always gave unstintingly of her time and energy whenI needed it. Throughout my graduate career, Peter Brown has been a steadfast source of encouragement and hands-on training, as well as an exampleof how to be a wonderful teacher while retaining one’s grounded humanity.Finally, Bruce Knauft has been an incredibly generous, profoundly insightful, and truly outstanding advisor, and has also been instrumental in mystaying the course and embarking on my current academic path. I only hopeI can be half as generous, supportive, intellectually stimulating, and loyalto my own advisees and students as Bruce was to me. I would also like tothank three other faculty members at Emory: Charles Nuckolls and CarolWorthman for their patience, encouragement, and support during my firstcouple of years at Emory, and Deborah McFarland for her enthusiasm andsupport of my work during my later, brief sojourn through the School ofPublic Health.I owe an intellectual debt of gratitude to a number of individuals whohave read this book or sections of it in manuscript form and providedme with invaluable suggestions. I am particularly grateful to LawrenceCohen, Serena Nanda, Elena Gutierrez, Laurie Schaffner, Peg Strobel, JudyGardiner, Biju Rao, Micaela di Leonardo, Vinay Swamy, Sylvia Vatuk,Jennifer Brier, William Wolf, Donna Murdock, and Emily Bloch, who gavegenerously of their time in reading, commenting on, and greatly improving parts or the whole of this manuscript. I would also like to thankCorinne Louw for her meticulous and invaluable assistance in preparingthe final draft of the manuscript for publication. To the participants in mydissertation-writing seminar from 1997 to 1999, especially Holly Wardlow,Daniel Smith, and Andrew Cousins (and Don Donham for doing such asuperb job of facilitating this seminar)—I could not have finished without you. Thank you for your extremely valuable critiques and suggestions,your steady encouragement and validation, and your constant presence andsupport—over endless shared pitchers of beer and cigarettes—through allthe ups and downs of agonizing over and writing the dissertation. I thankWendy Doniger and Kira Hall for generously making available their unpublished material. For their friendship, love, support, and encouragementover the years, I would also like to thank Edith Aubin, C. S. Balachandran,

Acknowledgments / xiTassi Crabb, Beatrice Greco, Russ Hanford, Aditya Kar, Alice Long, KeithMcNeal, Gowri Meda, Fabien Richards, Elaine Salo, Sumati Surya, ShaunaSwartz, Deepa and Rajesh Talpade, Mayuresh Tapale and all the otherwonderful Trikone folk in Atlanta, my father, Vasunder Reddy, my aunt,Jyothi Rao, Saras and G. K. Reddy, and other supportive members of myfamily in Hyderabad, as well as Yamini Atmavilas, Lara Deeb, Jessica Gregg,Benjamin Junge, Anil Lal, Wynne Maggi, Mark Padilla, Rebecca Seligman,Malcolm Shelley, and Anu Srinivasan.At the University of Illinois, I would like to thank the faculty andstaff of both my departments—Gender and Women’s Studies as well asAnthropology—for their support and encouragement of my work. I wouldespecially like to thank my colleagues Elena Gutierrez, Peg Strobel, JudyGardiner, Sylvia Vatuk, and Laurie Schaffner for their extremely valuablecomments on drafts of this manuscript. In addition, I would like to thankLynette Jackson, Krista Thompson, Mark Liechty, Yasmin Nair, Javier VillaFlores, John D’Emilio, Jim Oleson, Sandy Bartky, Beth Richie, JenniferLangdon-Teclaw, Helen Gary, Emily LaBarbera-Twarog, Corinne Louw, andJill Gage for making this new academic space intellectually challenging andstimulating, as well as wonderfully collegial and supportive for me. Finally, Iwould like to thank Ray Brod and his able assistants at the UIC CartographyLaboratory for preparing the map for this volume.At the Press, I am profoundly grateful to series editor Gilbert Herdt, executive editor Douglas Mitchell, and editorial associate Timothy McGovern.From the very beginning, they have been enthusiastic, generous, and patient as I negotiated the various twists and turns of the publication process.I am very grateful to Nick Murray for his excellent editorial skills and formaking this book more accessible to a wider audience. I am greatly indebtedto the two anonymous readers of the manuscript for their incredibly careful, brilliantly critical, and constructive readings of the text. Their insightfulcomments and gentle efforts to push my analyses have vastly improved themanuscript. Any misinterpretations and omissions are solely my responsibility.Perhaps my greatest personal debt is to my sister, Sita Reddy, withoutwhose guidance, love, support, and constant encouragement I would neither have embarked on a career in anthropology nor successfully navigatedgraduate school, chosen the present topic, or concluded this project. To her Iowe more than an intellectual debt of gratitude. It is thanks to her enduringsupport and belief in me—in addition to unstinting gifts of time and effortin reading multiple drafts of my chapters, often at the last minute—thatthis book could be written. Thank you, Sita.

note on transliterationFor ease of reading, I have chosen not to use diacritics in transliteratingnon-English words in the text and have transliterated these words withappropriate diacritical marks only in the glossary. In the text, non-Englishwords have been italicized. Those used most frequently have been italicizedonly the first time they appear, for example, hijra, koti, cela, izzat, and soforth.

1The Ethnographic SettingIt wasn’t until a few weeks after I began fieldwork among hijras in theSouth Indian twin cities of Hyderabad and Secunderabad that I had myfirst inkling of their perceptions of me. I was sitting on a mat, chatting withMunira, who later became one of my closest hijra friends. She was tellingme proudly about her last visit to Mumbai when she had been approachedby a journalist for her story, and how she had rebuffed him. Munira thenturned to me and said, somewhat apologetically, “I hope you don’t mind mysaying this. But you know, Gayatri, when I first saw you, I thought, ‘She hasthe body and face of a woman, she is wearing female clothing, but she hassuch short hair. Maybe she is a young boy of thirteen or fourteen.’ That is thereason I spoke to you initially, you know. I thought maybe, maybe you wereone of us at first.” Then, laughing aloud, she added, “Frankly, I don’t knowhow I thought that you might be. You are, you know, different-looking, sothat is what I thought then.”I begin with this incident to highlight two issues of access and representation: First, of course, was hijras’ perception of my appearance—as ayoung Indian, somewhat “different-looking” from them, with uncommonlyshort hair for a woman. Second, as I gradually learned over the course ofmy fieldwork, they attributed this difference not to my sexuality or sexualorientation, but to my upper-middle-class status. My short hair, my “ethnically chic” Fab India salwar-kurta,1 my educational background, my statusas an unmarried woman, especially given my age, and my engagement inthis academic project with hijras—factors that lead to a presumption aboutmy sexual identity here in the United States—were, for hijras, signs of myclass identification.Quite apart from privileging a particular theory, history, and politics ofrepresentation, I raise this issue to underscore a fairly simple point: the notion that sexual difference is not the only lens through which hijras perceive

2 / Chapter Onethe world and expect in turn to be perceived. In other words, as I maintainthroughout this ethnography, hijras are not just a sexual or gendered category, as is commonly contended in the literature (e.g., Vyas and Shingala1987; Sharma 1989; Nanda 1990). Like the members of any other community in India, their identities are shaped by a range of other axes. Thoughsex/gender is perhaps the most important of these axes, hijra identity cannot be reduced to this frame of analysis.2 Through a description of hijras’lives, this book explores the domain of sexuality as well as its articulationwith broader contexts of everyday life in South Asia, including aspects ofkinship, religion, class, and hierarchies of respect. Before exploring issues ofrepresentation and hijras’ historical and geographic representation in particular, however, I provide a brief introductory note about hijras for thoseunfamiliar with these metonymic figures of Indian sexual difference.the hyper (in)visibility of hijrasFor the most part, hijras are phenotypic men who wear female clothingand, ideally, renounce sexual desire and practice by undergoing a sacrificialemasculation—that is, an excision of the penis and testicles—dedicated tothe goddess Bedhraj Mata. Subsequently they are believed to be endowedwith the power to confer fertility on newlyweds or newborn children. Theysee this as their “traditional” ritual role, although at least half of the current hijra population (at least in Hyderabad) engages in prostitution, whichhierarchically senior “ritual specialists” greatly disparage.3 In recent years,hijras have emerged as perhaps the most frequently encountered figures inthe narrative linking of India with sexual difference. As the quintessential“third sex” of India, they have captured the Western scholarly imaginationas an ideal case in the transnational system of “alternative” gender/sexuality.In such analyses, the hijra (or Thai kathoey or Omani xanith, among others)becomes, as Rosalind Morris notes, either an “interstitial gender occupyingthe liminal space between male and female,” or “a ‘drag queen’ who [is] ahero(ine) in a global sexual resistance” (1994, 16). With this specularizationhas come an intense gaze directed at hijras by both scholars and the press.By their own accounts, hijras in most major cities—including the SouthIndian city of Hyderabad, where I did my research—have been drivencrazy by foreigners or, to translate the more colorful Hindi phrase, havehad their “minds eaten by foreign [ firangi] people” desperate to capture astory for their audience. In the last decade or so, there have been at leastfour documentaries or news features (Kalliat 1990; Prasad and Yorke 1991;

The Ethnographic Setting / 3Cooper 1999; Shiva, MacDonald, and Gucovsky 2000), four ethnographiesor book-length monographs (Nanda 1990; Jaffrey 1996; Balaji and Malloy1997; Ahmed and Singh 2002), three books of fiction (Mann 1992; Sinha1993; Forbes 1998), at least two dissertations (Hall 1995; Reddy 2000), andseveral undergraduate honors theses that focus explicitly on hijras. Morerecently, hijras have also been “mainstreamed” into the Indian world of popular films.4 In some ways, this is in marked contrast to the earlier ambivalent yet arguably tolerant attitude of most Indians toward them. For manyIndians—both upper- and middle-class—hijras exist (and to some extenthave always existed) at the periphery of their imaginaries, making themselves visible only on certain circumscribed ritual occasions. Given thishistory of near invisibility, the recent attention focused on hijras has beenunsettling for both hijras and non-hijras.In response to this seemingly boundless interest, hijras have becomemore wary of scholars and journalists alike, and this attention has alsoheightened scrutiny by local disciplinary regimes, including the police.5Just before I arrived in Hyderabad for my fieldwork, a case was registeredagainst the senior hijras in the old city by a family that claimed their sonhad been abducted by the hijra community.6 Even though the case waslater dismissed, hijras told me they felt overly scrutinized for the first timein hundreds of years. Partly in response to this heightened sensitivity onthe part of the hijra community, but also, I suspect, out of a patriarchalconcern that this was not a “proper” topic for an Indian woman to beresearching (see Jaffrey 1996), I was explicitly advised by anthropologists,several relatives, and even strangers to steer clear of hijras in Hyderabad.Needless to say, the atmosphere within the hijra community, especially withregard to interactions with non-hijras, was somewhat tense when I beganmy research in the fall of 1995.For all these reasons, I was well aware that by undertaking this projectI might, however unwittingly, increase hijras’ visibility within disciplinaryregimes in India, resulting in greater scrutiny of their lives. In recent years,with the increasing visibility of hijras in global compendia of sexuality/gender and the growth of the gay movement in India, hijras, self-identifiedgay men, and men cruising for sex with other men in public spaces have become increasingly visible to the police, the media, and ruffians, or goondas.Just in the last few years, there have been at least two dramatic disruptionsand arrests of volunteers in nongovernmental organizations that work on issues relating to sexual health—and more specifically, the health of MSM, ormen who have sex with men—quite apart from the innumerable incidentsof everyday harassment and surveillance. Despite this greater vigilance and

4 / Chapter Onemy anxiety on this account, however, many hijras I encountered in Hyderabad explicitly reiterated their desire to get the real story of their livesdown on paper, as much in response to this scrutiny as to vindicate theirlife choices. Although aware of the irony of their positions and the potentialfor even greater vilification on account of the publicity, hijras with whomI worked most closely were eager to “tell [their] stories” so that “everyone[would] know about [their] lives.”In undertaking this project, I am also concerned that my focusing onhijras within the current frame of academic inquiry that explicitly emphasizes their sexual difference—even if my intention is expressly to refocusthis gaze—inevitably privileges this mode of discourse. I grew up in Indiawell aware of the existence of hijras, and even though I was not immersedin their lives, I have to question why my intellectual curiosity was notsufficiently piqued until I came to the United States for graduate studies. Or maybe the question should not be when and why did I remember,but when and why did I forget? What sorts of erasures—of class, caste,gender, or sexuality—were encoded in my previous silence and ongoingrefraction of the hijra “category” (see Patel 1997)? More specifically, whatkinds of occlusions of class and sexual privilege do these conceal/revealin both (upper-middle-class) India and the U.S. academe? In other words,perhaps we need to be aware of the history and politics of particular discursive and theoretical lenses—the marked categories/discourses that mightappear salient in one arena but less so in another (see Uberoi 1996; Thapan1997; John and Nair 1998). This is not to imply that sex and sexuality arenot important or even central to hijras’ lives. It merely emphasizes the needto contextualize our analytic and personal agendas in any representationalendeavor. Hence, viewing hijras solely within the framework of sex/genderdifference—as the quintessential “third sex” or “neither men nor women”—ultimately might be a disservice to the complexity of their lives and theirembeddedness within the social fabric of India.Further, although this project explicitly attempts to subvert the reification or commodification of a third category—making hijras’ lives count asmuch as it addresses various “categories” of sexual thirdness—to the extent that it multiplies rather than dismantles third genders/categories, I amsomewhat uneasy that it might reaffirm as much as it subverts, nominalizing, numericalizing, and naturalizing embodied difference in its wake.There is, after all, as Kath Weston notes, “a relationship of longstanding[sic] between counting and commodification” that one must be aware ofwhen embarking on such a project as this (2002, 41).

The Ethnographic Setting / 5Finally, my ambivalence in undertaking this research also relates to theexclusions sustained (or produced) by such a project. To what extent doesthe focus on hijras as male-to-hijra subject-positions contribute, even unintentionally, to the continuing discursive and systemic violence againstwomen? As Lawrence Cohen (1995b) observes, highlighting shifts frommale (rather than female) to a third-gender identity erases the politicaldifferences between male and female experiences and, ultimately, workswithin a two-gendered system—male and third—in which the female position has been virtually erased. In a somewhat similar vein, speaking forthe Thai context, Rosalind Morris (1994) points out that patriarchal narratives seem to have “effaced [if it ever existed] any expression of femalesexual identity that could not be subsumed under a reproductive mandate”(1994, 26). In this ideology, femaleness is thoroughly naturalized as reproductive capacity. Only in the recent past, with the emergence of sexualitiesdefined in terms of object choice, has the category of woman been differentiated into hetero- and homosexual identities. Perhaps the important historical and empirical question (as Morris asks with respect to the kathoeys ofThailand) is “[H]ow have sex/gender systems [in both Thailand and India,apparently] organized the somatic economy in such a way as to render both‘female’ and ‘male’ bodies as media of masculine subjectivities?” (1994, 25).While this is not the question I explore in this book, I argue that it is animportant one to keep in mind—along with the other issues of ambivalenceand (inadvertent) silencing noted above—as one explores issues of sexualdifference and the place of hijras within that context.framing the setting: the twin cities of hyderabadand secunderabadOn the flight from Frankfurt to Delhi on my way to begin fieldwork, Iwas sitting next to a British art historian who was a frequent traveler toIndia. In the course of conversation, he asked me what I did for a living andwhether Delhi was my final destination in India. “I’m an anthropologist andI’m going to [the South Indian city of] Hyderabad to do an ethnographicstudy of this one community—hijras—now fairly well-known as the ‘thirdsex’ of India,” I replied, expecting to expand on this theme.7 Instead, heappeared far more curious about the city of Hyderabad, having heard it was“different” from other Indian cities on account of its Muslim influence.8 Byway of an initial response to his questions about the city, I told him the

6 / Chapter Oneclassic tale of the founder of the city, Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah,9 and hislove for his wife, Hyder Begum, after whom the city was named, a story thatin many ways captures the issues central to Hyderabadi hijra identity—loveor desire, religious pluralism, and the history of Muslim influence in thecity.As the popular legend goes, before his ascension to the throne, Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, an excellent equestrian, often exercised his horse inthe area surrounding the fort of Golconda. One day, on one of his extendedrides, he stopped at the village of Chichlam for a drink of water.10 Passingby at that moment on her way to the temple was Bhagmati, the daughterof Lingayya, a relatively poor Hindu resident of Chichlam village. Muhammad Quli was immediately taken by her beauty and grace, and began tovisit the spot frequently, incognito, to catch a glimpse of Bhagmati and winher affections. When Muhammad Quli ascended the throne as the ruler ofGolconda a few years later, he sent for Bhagmati’s father and asked for herhand in marriage. Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah and Bhagmati were marriedin 1596 CE and, as the legend goes, lived happily together until MuhammadQuli’s untimely death in 1612.During his reign, Muhammad Quli founded a new city ten miles eastof Golconda on the southern bank of the Musi River in order to ease thecongestion and shortage of water in the crowded city of Golconda and, asfolk wisdom has it, to commemorate his love for his wife. The city wasinitially called Bhagnagar for Bhagmati, but its name was later changed toHyderabad following Bhagmati’s conversion to Islam and adoption of thetitle Hyder Begum. Hyderabad quickly became an important and bustlingcity. After the fall of Golconda to the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1687and the subsequent dissolution of the Mughal Empire, the first Nizam(as subsequent rulers of Hyderabad were known), Asaf Jah I, chose thiscity rather than the walled fort of Golconda for his capital, with Charminarserving as the heart of the city. Charminar, which literally means “fourminarets,” continues to symbolize and function as the center of what isknown as the “old city” of Hyderabad.Quite apart from the documented antiquity of hijras in this city (Lyntonand Rajan 1974; Jaffrey 1996), the reasons I chose this city as the locus of mystudy are captured in some measure by this origin myth/historical folktale.Two issues are worth mentioning here: The first relates to the importance ofIslam for the larger part of Hyderabad’s history, although this influence hasalways been balanced by a significant Hindu counterinfluence. The mutual engagement and tension between the Muslim and Hindu presence inthis region is unique in the South Indian experience. Hyderabad and its

Map of Hyderabad and Secunderabad

8 / Chapter Onesurrounding region have constituted the only continuously Muslim-ruledarea in South India for the past five centuries, and this influence is apparenteven today. More important for the current context was my interest in therelation between present-day hijra identity and the history of Muslim patronage, given the recorded history of eunuchs in the Islamic royal courts ofthe Mamluk Sultanate and in the Byzantine and Ottoman empires (Peirce1993; Marmon 1995; Ayalon 1999) in addition to their presence in medievalIndian history. As several authors have noted, eunuchs in India were oftenaccorded respect in the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal courts, holding positions of eminence especially under the Khiljis of Delhi in the thirteenth andfourteenth centuries and under the Mughals from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. Although many eunuchs were initially brought as slavesinto the houses of Muslim nobility in principalities such as Awadh and Hyderabad, they were accorded respect and trusted with sensitive positions,including guarding the harim, or inner/female spaces within the palace(Knighton 1855; Bernier 1891; Manucci 1907; Saletore 1974; Kidwai 1985;Chatterjee 1999, 2002).With respect to the second issue, perhaps as a legacy of MuhammadQuli’s love for Hyder Begum, Hyderabad is also popularly known in sometourist brochures as India’s “city of love,” complete with the local version ofthe Pont Neuf spanning the Musi River. Interestingly, some tension existsbetween this idealized love and other contemporary images of Hyderabad,as captured by the adage that a hijra laughingly related to me. She said,“Delhi dilwalon ka, Bombay paisewalon ka, aur Hyderabad randiyon ka”(Delhi stands for those who have love, Bombay for those with money; andHyderabad for whores). As I explain in the following pages, these idioms of“romantic” and “modern” love, or desire if you will, played out in interestingways in the lives of the hijras I came to know, not only in terms of theiroccupation, their position in the hijra kinship hierarchy, their dis/avowal ofsexual desire, and their degree of respect, but also in terms of their spatiallocation in the twin cities of Hyderabad and Secunderabad.the spatial history of hyderabadi hijrasThe actual number of hijras in India is in dispute, ranging from ten thousandto two million (Bobb and Patel 1982; Jaffrey 1996). The popular beli

The Bedtrick: Tales of Sex and Masquerade by Wendy Doniger Money, Myths, and Change: The Economic Lives of Lesbians and Gay Men by M. V. Lee Badgett The Night Is Young: Sexuality in Mexico in the Time of AIDS by He ctor Carrillo The Emerging Lesbian: Female Same-Sex Desire in Modern China by Tze-lan D. Sang CoyoteNation:Sexuality,Race,andConquest