Transcription

C HAPTER 71772Somerset case1777Articles of Confederationdrafted1781Articles of Confederationratified1782Letters from an AmericanFarmer1784– Land Ordinances approved17851785Jefferson’s Notes on the Stateof Virginia1786– Shays’s Rebellion17871787Northwest Ordinance of 1787Constitutional Conventionconvened1788The FederalistConstitution ratified1790Naturalization Act1791Bill of Rights ratifiedLittle Turtle defeats ArthurSt. Clair’s forces1794Little Turtle defeated at Battleof Fallen Timbers1795Treaty of Greenville1808Congress prohibits the slavetrade

Founding a Nation,1783–1789AMERICA UNDER THECONFEDERATIONThe Articles of ConfederationCongress and the WestSettlers and the WestThe Land OrdinancesThe Confederation’sWeaknessesShays’s RebellionNationalists of the 1780sSlavery in the ConstitutionThe Final DocumentTHE RATIFICATION DEBATEAND THE ORIGIN OF THEBILL OF RIGHTSThe Federalist“Extend the Sphere”The Anti-FederalistsThe Bill of RightsA NEW CONSTITUTION“WE THE PEOPLE”The Structure of GovernmentThe Limits of DemocracyThe Division and Separationof PowersThe Debate over SlaveryNational IdentityIndians in the New NationBlacks and the RepublicJefferson, Slavery, and RacePrinciples of FreedomIn this late eighteenth-century engraving, Americans celebrate the signing of theConstitution beneath a temple of liberty.

F OCUS Q UESTIONS What were the achievements and problems ofthe Confederationgovernment? What major disagreements and compromisesmolded the final content ofthe Constitution? How did Anti-Federalistconcerns raised during theratification process lead tothe creation of the Bill ofRights? How did the definition ofcitizenship in the newrepublic exclude NativeAmericans and AfricanAmericans?l During June and July of 1788, civic leaders in cities up and down theAtlantic coast organized colorful pageants to celebrate theratification of the United States Constitution. For one day, BenjaminRush commented of Philadelphia’s parade, social class “forgot itsclaims,” as thousands of marchers—rich and poor, businessman andapprentice—joined in a common public ceremony. New York’sGrand Federal Procession was led by farmers, followed by the members ofevery craft in the city from butchers and coopers (makers of woodenbarrels) to bricklayers, blacksmiths, and printers. Lawyers, merchants, andclergymen brought up the rear. The parades testified to the strong popularsupport for the Constitution in the nation’s cities. And the prominent roleof skilled artisans reflected how the Revolution had secured their place inthe American public sphere. Elaborate banners and floats gave voice tothe hopes inspired by the new structure of government. “May commerceflourish and industry be rewarded,” declared Philadelphia’s mariners andshipbuilders.Throughout the era of the Revolution, Americans spoke of their nationas a “rising empire,” destined to populate and control the entire NorthAmerican continent. While Europe’s empires were governed by force,America’s would be different. In Jefferson’s phrase, it would be “an empireof liberty,” bound together by a common devotion to the principles of theDeclaration of Independence. Already, the United States exceeded in sizeGreat Britain, Spain, and France combined. As a new nation, it possessedmany advantages, including physical isolation from the Old World (asignificant asset between 1789 and 1815, when European powers werealmost constantly at war), a youthful population certain to grow muchlarger, and a broad distribution of property ownership and literacy amongwhite citizens.On the other hand, while Americans dreamed of economic prosperityand continental empire, the nation’s prospects at the time of independencewere not entirely promising. Control of its vast territory was by no meanssecure. Nearly all of the 3.9 million Americans recorded in the first nationalcensus of 1790 lived near the Atlantic coast. Large areas west of theAppalachian Mountains remained in Indian hands. The British retainedmilitary posts on American territory near the Great Lakes, and therewere fears that Spain might close the port of New Orleans to Americancommerce on the Mississippi River.Away from navigable waterways, communication and transportationwere primitive. The country was overwhelmingly rural—fewer than oneAmerican in thirty lived in a place with 8,000 inhabitants or more. Thepopulation consisted of numerous ethnic and religious groups andsome 700,000 slaves, making unity difficult to achieve. No republicangovernment had ever been established over so vast a territory or with so

What were the achievements and problems of the Confederation government?diverse a population. Local loyalties outweighed national patriotism. “Wehave no Americans in America,” commented John Adams. It would taketime for consciousness of a common nationality to sink deep roots.Today, with the United States the most powerful country on earth, it isdifficult to recall that in 1783 the future seemed precarious indeed for thefragile nation seeking to make its way in a world of hostile great powers.Profound questions needed to be answered. What course of developmentshould the United States follow? How could the competing claims of localself-government, sectional interests, and national authority be balanced?Who should be considered full-fledged members of the American people,entitled to the blessings of liberty? These issues became the focus of heated debate as the first generation of Americans sought to consolidate theirnew republic.A M E R I C A U N D E R T H E C O N F E D E R AT I O NTHEARTICLESOFCONFEDERATIONThe first written constitution of the United States was the Articles ofConfederation, drafted by Congress in 1777 and ratified by the states fouryears later. The Articles sought to balance the need for national coordination of the War of Independence with widespread fear that centralizedpolitical power posed a danger to liberty. It explicitly declared the newnational government to be a “perpetual union.” But it resembled less a blueprint for a common government than a treaty for mutual defense—in itsown words, a “firm league of friendship” among the states. Under theArticles, the thirteen states retained their individual “sovereignty, freedom,and independence.” The national government consisted of a one-houseCongress, in which each state, no matter how large or populous, cast a singlevote. There was no president to enforce the laws and no judiciary to interpret them. Major decisions required the approval of nine states rather thana simple majority.The only powers specifically granted to the national government bythe Articles of Confederation were those essential to the struggle forindependence—declaring war, conducting foreign affairs, and makingtreaties with other governments. Congress had no real financial resources.It could coin money but lacked the power to levy taxes or regulate commerce. Its revenue came mainly from contributions by the individualstates. To amend the Articles required the unanimous consent of the states,a formidable obstacle to change. Various amendments to strengthen thenational government were proposed during the seven years (1781–1788)when the Articles of Confederation were in effect, but none received theapproval of all the states.259

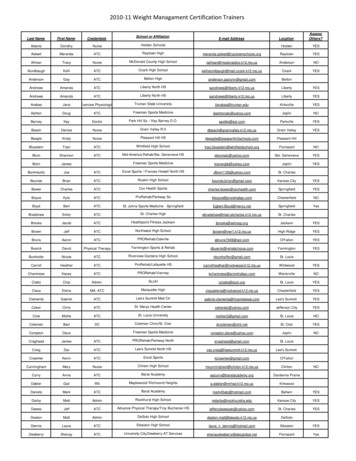

260C H . 7 Founding a Nation, 1783 –1789WESTERNLANDS,AMERICA UNDER THE NEWCeded by VIRGINIA, 1784NEW YORK HAMPSHIREoiOntarLakeMASSACHUSETTSCeded byCeded by MASSACHUSETTS, 1785MASSACHUSETTS,and VIRGINIA, 17841786rieRHODE ISLANDCeded byeEkaCONNECTICUT,Ceded by CONNECTICUT, 1786LCONNECTICUT1782and VIRGINIA, 1784NEWPENNSYLVANIACeded byJERSEYCONNECTICUT, 1800MARYLANDDELAWARECeded by VIRGINIA, 1784 Ohio R.LHudson R.u ro nR.MAINE(part of Massachusetts)eHpi.akiMss issiprioRceenSt. LaLak e SupewrBRITISH CANADAVIRGINIASPANISHLOUISIANACeded byVIRGINIA, 1792Ceded bySOUTH CAROLINA,1787NORTHCAROLINACeded by NORTH CAROLINA,1790SOUTHCAROLINACeded by GEORGIA, 1802GEORGIAAtlanticO cea nCeded by SPAIN, 1795Ceded by GEORGIA, 1802SPANISHFLORIDAGulf of Mexico00100200 milesStates after land cessionsCeded territoryTerritory ceded by New York, 1782100 200 kilometersThe creation of a nationally controlled public domain from western land cededby the states was one of the main achievements of the federal government under theArticles of Confederation.

What were the achievements and problems of the Confederation government?The Articles made energetic national government impossible. But Congress in the 1780s did not lack for accomplishments. The most importantwas establishing national control over land to the west of the thirteenstates and devising rules for its settlement. Disputes over access to western land almost prevented ratification of the Articles in the first place.Citing their original royal charters, which granted territory running allthe way to the “South Sea” (the Pacific Ocean), states like Virginia, theCarolinas, and Connecticut claimed immense tracts of western land. Landspeculators, politicians, and prospective settlers from states with clearlydefined boundaries insisted that such land must belong to the nationat large. Only after the land-rich states, in the interest of national unity,ceded their western claims to the central government did the Articles winratification.CONGRESSANDTHEWESTEstablishing rules for the settlement of this national domain—the areacontrolled by the federal government, stretching from the western boundaries of existing states to the Mississippi River—was by no means easy.Although some Americans spoke of it as if it were empty, some 100,000Indians in fact inhabited the region. In the immediate aftermath of independence, Congress took the position that by aiding the British, Indianshad forfeited the right to their lands. Little distinction was made amongtribes that had sided with the enemy, those that had aided the patriots, andthose in the interior that had played no part in the war at all. At peace conferences at Fort Stanwix, New York, in 1784 and Fort McIntosh nearPittsburgh the following year, American representatives demanded andreceived large surrenders of Indian land north of the Ohio River. Similartreaties soon followed with the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw tribesin the South, although here Congress guaranteed the permanency of theIndians’ remaining, much-reduced holdings. The treaties secured nationalcontrol of a large part of the country’s western territory.When it came to disposing of western land and regulating its settlement,the Confederation government faced conflicting pressures. Many leadersbelieved that the economic health of the new republic required that farmers have access to land in the West. But they also saw land sales as a potential source of revenue and worried that unregulated settlement would produce endless conflicts with the Indians. Land companies, which lobbiedCongress vigorously, hoped to profit by purchasing real estate and resellingit to settlers. The government, they insisted, should step aside and allowprivate groups to take control of the West’s economic development.SETTLERSANDTHEWESTThe arrival of peace meanwhile triggered a large population movementfrom settled parts of the original states into frontier areas like upstate NewYork and across the Appalachian Mountains into Kentucky and Tennessee.To settlers, the right to take possession of western lands and use them as theysaw fit was an essential element of American freedom. When a group ofOhioans petitioned Congress in 1785, assailing landlords and speculators261

262C H . 7 Founding a Nation, 1783 –1789AMERICA UNDER THE CONFEDERATIONAn engraving from The Farmer’s andMechanics Almanac shows farmfamilies moving west along a primitiveroad.who monopolized available acreage and asking that preference in landownership be given to “actual settlements,” their motto was “Grant usLiberty.” Indeed, settlers paid no heed to Indian land titles and urged thegovernment to set a low price on public land or give it away. They frequently occupied land to which they had no legal title. By the 1790s, Kentuckycourts were filled with lawsuits over land claims, and many settlers lostland they thought they owned. Eventually, disputes over land forced manyearly settlers (including the parents of Abraham Lincoln) to leaveKentucky for opportunities in other states.At the same time, however, like British colonial officials before them,many leaders of the new nation feared that an unregulated flow of population across the Appalachian Mountains would provoke constant warfarewith Indians. Moreover, they viewed frontier settlers as disorderly andlacking in proper respect for authority—“our debtors, loose English people,our German servants, and slaves,” Benjamin Franklin had once called them.Establishing law and order in the West and strict rules for the occupationof land there seemed essential to attracting a better class of settlers to theWest and avoiding discord between the settled and frontier parts of thenew nation.THELANDORDINANCESA series of measures approved by Congress during the 1780s defined the termsby which western land would be marketed and settled. Drafted by ThomasJefferson, the Ordinance of 1784 established stages of self-government forthe West. The region would be divided into districts initially governedby Congress and eventually admitted to the Union as member states. By asingle vote, Congress rejected a clause that would have prohibited slavery

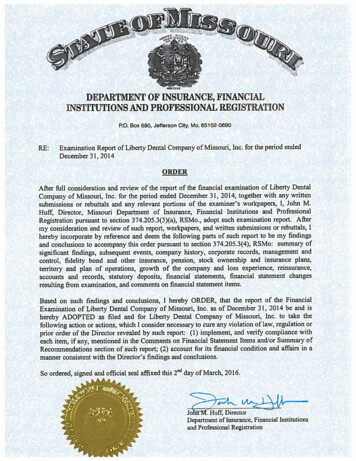

263What were the achievements and problems of the Confederation TH AMERICA(CANADA)R.MAINE(part of Massachusetts)St.LawrenceLake SuperiorFortMichilimackinacLakeErNEW YORKieOHIO(1803)INDIANA(1816)MASSACHUSETTSRHODE ISLANDCONNECTICUTNEWJERSEYMARYLAND.200 milesNORTH CAROLINATENNESSEE (1796)THE SEVEN RANGESFirst Area SurveyDETAIL OF TOWNSHIP36 square 2726253132333435361 mileA series of ordinances in the 1780s provided for both the surveying and saleof lands in the public domain north of the Ohio River and the eventual admission ofstates carved from the area as equal members of the Union.Income from section 16reserved for school supportDETAIL OF SECTION1 square mile (640 acres)Half-section(320 acres)1 mileVIRGINIAPENNSYLVANIA7th Range6th Range5th Range4th Range3rd Range2nd Range1st Range6 milesA t l a n ti cO cea nFortsDisputed boundariesNorthwest TerritoryKENTUCKY(1792)200 kilometers6 milesDELAWAREVIRGINIAOhi100OswegoHudson R.iganLake Michu ro ni R.FortNiagaraFortDetroitoR100oe akWISCONSIN(1848)Mis sisPointau-FerLHalf-quarter-section(80 acres)Quarter-quarter-section(40 acres each)Quarter-section(160 acres)

264C H . 7 Founding a Nation, 1783 –1789AMERICA UNDER THE CONFEDERATIONthroughout the West. A second ordinance, in 1785, regulated land sales inthe region north of the Ohio River, which came to be known as the OldNorthwest. Land would be surveyed by the government and then sold in“sections” of a square mile (640 acres) at 1 per acre. In each township, onesection would be set aside to provide funds for public education. The system promised to control and concentrate settlement and raise money forCongress. But settlers violated the rules by pressing westward before thesurveys had been completed.Like the British before them, American officials found it difficult toregulate the thirst for new land. The minimum purchase price of 640,however, put public land out of the financial reach of most settlers. Theygenerally ended up buying smaller parcels from speculators and landcompanies. In 1787, Congress decided to sell off large tracts to privategroups, including 1.5 million acres to the Ohio Company, organized byNew England land speculators and army officers. (This was a differentorganization from the Ohio Company of the 1750s, mentioned in Chapter4.) For many years, national land policy benefited private land companiesand large buyers more than individual settlers. And for many decades, actual and prospective settlers pressed for a reduction in the price of government-owned land, a movement that did not end until the Homestead Act of1862 offered free land on the public domain.A final measure, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, called for the eventual establishment of from three to five states north of the Ohio River andeast of the Mississippi. Thus was enacted the basic principle of whatJefferson called the “empire of liberty”—rather than ruling over the Westas a colonial power, the United States would admit the area’s population asequal members of the political system. Territorial expansion and selfgovernment would grow together.The Northwest Ordinance pledged that “the utmost good faith” would beobserved toward local Indians and that their land would not be taken without consent. This was the first official recognition that Indians continuedto own their land. Congress realized that allowing settlers and state government simply to seize Indian lands would produce endless, expensive military conflicts on the frontier. “It will cost much less,” one congressmannoted, “to conciliate the good opinion of the Indians than to pay men fordestroying them.” But national land policy assumed that whether throughpurchase, treaties, or voluntary removal, the Indian presence would soondisappear. The Ordinance also prohibited slavery in the Old Northwest, aprovision that would have far-reaching consequences when the sectionalconflict between North and South developed. But for years, ownersbrought slaves into the area, claiming that they had voluntarily signedlong-term labor contracts.THECONFEDERATION’SWEAKNESSESWhatever the achievements of the Confederation government, in theeyes of many influential Americans they were outweighed by its failings. Both the national government and the country at large faced worsening economic problems. To finance the War of Independence,Congress had borrowed large sums of money by selling interest-bearingbonds and paying soldiers and suppliers in notes to be redeemed in the

What were the achievements and problems of the Confederation government?265future. Lacking a secure source of revenue, it found itself unable to payeither interest or the debts themselves. With the United States now outside the British empire, American ships were barred from trading withthe West Indies. Imported goods, however, flooded the market, undercutting the business of many craftsmen, driving down wages, and draining money out of the country.With Congress unable to act, the states adopted their own economicpolicies. Several imposed tariff duties on goods imported from abroad.Indebted farmers, threatened with the loss of land because of failure tomeet tax or mortgage payments, pressed state governments for relief, as didurban craftsmen who owed money to local merchants. In order to increasethe amount of currency in circulation and make it easier for individuals topay their debts, several states printed large sums of paper money. Othersenacted laws postponing debt collection. Creditors considered such measures attacks on their property rights. In a number of states, legislative elections produced boisterous campaigns in which candidates for officedenounced creditors for oppressing the poor and importers of luxury goodsfor undermining republican virtue.SHAYS’SREBELLIONIn late 1786 and early 1787, crowds of debt-ridden farmers closed the courtsin western Massachusetts to prevent the seizure of their land for failure topay taxes. They called themselves “regulators”—a term already used byprotesters in the Carolina backcountry in the 1760s. The uprising came tobe known as Shays’s Rebellion, a name affixed to it by its opponents, afterDaniel Shays, one of the leaders and a veteran of the War for Independence.Massachusetts had firmly resisted pressure to issue paper money or inother ways assist needy debtors. The participants in Shays’s Rebellionbelieved they were acting in the spirit of the Revolution. They modeledtheir tactics on the crowd activities of the 1760s and 1770s and employedliberty trees and liberty poles as symbols of their cause. They received nosympathy from Governor James Bowdoin, who dispatched an army headedby former revolutionary war general Benjamin Lincoln. The rebels weredispersed in January 1787, and more than 1,000 were arrested. Withoutadherence to the rule of law, Bowdoin declared, Americans would descendinto “a state of anarchy, confusion and slavery.”Observing Shays’s Rebellion from Paris where he was serving as ambassador, Thomas Jefferson refused to be alarmed. “A little rebellion now and thenis a good thing,” he wrote to a friend. “The tree of liberty must be refreshedfrom time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” But the uprisingwas the culmination of a series of events in the 1780s that persuaded aninfluential group of Americans that the national government must bestrengthened so that it could develop uniform economic policies and protect property owners from infringements on their rights by local majorities.The actions of state legislatures (most of them elected annually by anexpanded voting population), followed by Shays’s Rebellion, produced fearsthat the Revolution’s democratic impulse had gotten out of hand.“Our government,” Samuel Adams wrote in 1785, “at present has libertyfor its object.” But among proponents of stronger national authority, liberty had lost some of its luster. The danger to individual rights, they came toA Bankruptcy Scene. Creditors repossessthe belongings of a family unable to payits debts, while a woman weeps in thebackground. Popular fears of bankruptcyled several states during the 1780s to passlaws postponing the collection of debts.

266C H . 7 Founding a Nation, 1783 –1789AMERICA UNDER THE CONFEDERATIONbelieve, now arose not from a tyrannical central government, but from thepeople themselves. “Liberty,” declared James Madison, “may be endangeredby the abuses of liberty as well as the abuses of power.” To put it anotherway, private liberty, especially the secure enjoyment of property rights,could be endangered by public liberty—unchecked power in the hands ofthe people.NATIONALISTSJames Madison, “father of theConstitution,” in a miniature portraitpainted by Charles Willson Peale in 1783.Madison was only thirty-six years oldwhen the Constitutional Convention met.Alexander Hamilton, another youthfulleader of the nationalists of the 1780s,was born in the West Indies in 1755.This portrait was painted by CharlesWillson Peale in the early 1790s.OFTHE1780SMadison, a diminutive, colorless Virginian and the lifelong disciple andally of Thomas Jefferson, thought deeply and creatively about the nature ofpolitical freedom. He was among the group of talented and well-organizedmen who spearheaded the movement for a stronger national government.Another was Alexander Hamilton, who had come to North America as ayouth from the West Indies, served at the precocious age of twenty as anarmy officer during the War of Independence, and married into a prominent New York family. Hamilton was perhaps the most vigorous proponentof an “energetic” government that would enable the new nation to becomea powerful commercial and diplomatic presence in world affairs. Genuineliberty, he insisted, required “a proper degree of authority, to make andexercise the laws.” Men like Madison and Hamilton were nation-builders.They came to believe during the 1780s that Americans were squanderingthe fruits of independence and that the country’s future greatness depended on enhancing national authority.The concerns voiced by critics of the Articles found a sympathetic hearing among men who had developed a national consciousness during theRevolution. Nationalists included army officers, members of Congressaccustomed to working with individuals from different states, and diplomats who represented the country abroad. In the army, John Marshall (latera chief justice of the Supreme Court) developed “the habit of consideringAmerica as my country, and Congress as my government.” Influential economic interests also desired a stronger national government. Among thesewere bondholders who despaired of being paid so long as Congress lackeda source of revenue, urban artisans seeking tariff protection from foreignimports, merchants desiring access to British markets, and all those whofeared that the states were seriously interfering with property rights.While these groups did not agree on many issues, they all believed in theneed for a stronger national government.In September 1786, delegates from six states met at Annapolis,Maryland, to consider ways for better regulating interstate and international commerce. The delegates proposed another gathering, inPhiladelphia, to amend the Articles of Confederation. Shays’s Rebelliongreatly strengthened the nationalists’ cause. “The late turbulent scenes inMassachusetts,” wrote Madison, underscored the need for a new constitution. “No respect,” he complained, “is paid to the federal authority.”Without a change in the structure of government, either anarchy ormonarchy was the likely outcome, bringing to an end the experiment inrepublican government. Every state except Rhode Island, which had gonethe farthest in developing its own debtor relief and trade policies, decidedto send delegates to the Philadelphia convention. When they assembled in

What were the achievements and problems of the Confederation government?267May 1787, they decided to scrap the Articles of Confederation entirely anddraft a new constitution for the United States.A NEW CONSTITUTIONThe fifty-five men who gathered for the Constitutional Convention included some of the most prominent Americans. Thomas Jefferson and JohnAdams, serving as diplomats in Europe, did not take part. But among thedelegates were George Washington (whose willingness to lend his prestigeto the gathering and to serve as presiding officer was an enormous asset),George Mason (author of Virginia’s Declaration of Rights of 1776), andBenjamin Franklin (who had returned to Philadelphia after helping tonegotiate the Treaty of Paris of 1783, and was now eighty-one years old).John Adams described the convention as a gathering of men of “ability,weight, and experience.” He might have added, “and wealth.” Few men ofordinary means attended. Although a few, like Alexander Hamilton, hadrisen from humble origins, most had been born into propertied families.They earned their livings as lawyers, merchants, planters, and large farmers. Nearly all were quite prosperous by the standards of the day.At a time when fewer than one-tenth of 1 percent of Americans attendedcollege, more than half the delegates had college educations. A majorityhad participated in interstate meetings of the 1760s and 1770s, and twentytwo had served in the army during the Revolution. Their shared social status and political experiences bolstered their common belief in the need tostrengthen national authority and curb what one called “the excesses ofdemocracy.” To ensure free and candid debate, the deliberations took placein private. Madison, who believed the outcome would have great consequences for “the cause of liberty throughout the world,” took careful notes.They were not published, however, until 1840, four years after he becamethe last delegate to pass away.THESTRUCTUREOFGOVERNMENTIt quickly became apparent that the delegates agreedon many points. The new Constitution would createa legislature, an executive, and a national judiciary.Congress would have the power to raise moneywithout relying on the states. States would be prohibited from infringing on the rights of property.And the government would represent the people.Hamilton’s proposal for a president and Senate serving life terms, like the king and House of Lords ofEngland, received virtually no support. The “richand well-born,” Hamilton told the convention,must rule, for the masses “seldom judge or determine right.” Most delegates, however, hoped to finda middle ground between the despotism of monarchy and aristocracy and what they considered theexcesses of popular self-government. “We had beenA fifty-dollar note issued by theContinental Congress during the Warof Independence. Congress’s inability toraise funds to repay such paper moneyin gold or silver was a major reason whynationalists desired a stronger federalgovernment.

268C H . 7 Founding a Nation, 1783 –1789The Philadelphia State House (now calledIndependence Hall), where the Declarationof Independence was signed in 1776 andthe Constitutional Convention took placein 1787.A NEW CONSTITUTIONtoo democratic,” observed George Mason, but he warned against the dangerof going to “the opposite extreme.” The key to stable, effective republicangovernment was finding a way to balance the competing claims of libertyand power.Differences quickly emerged over the proper balance between the federal and state governments and between the interests of large and smallstates. Early in the proceedings, Madison presented what came to be calledthe Virginia Plan. It proposed the creation of a two-house legislature with astate’s population determining its representation in each. Smaller states,fearing that populous Virginia, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania woulddominate the new government, rallied behind the New Jersey Plan. Thiscalled for a single-house Congress in which each state cast one vote, asunder the Articles of Confederation. In the end, a compromise wasreached—a two-house Congress consisting of a Senate in which each statehad two members, and a House of Representatives apportioned accordingto population. Senators would be chosen by state legislatures for six-yearterms. They were thus insulated from sudden shifts in public opinion.Representatives were to be elected every two years directly by the people.THELIMITSOFDEMOCRACYUnder the Artic

1772 Somerset case 1777 Articles of Confederation drafted 1781 Articles of Confederation ratified 1782 Letters from an American Farmer 1784- Land Ordinances approved 1785 1785 Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia 1786- Shays's Rebellion 1787 1787 Northwest Ordinance of 1787 Constitutional Convention convened 1788 The Federalist Constitution ratified 1790 Naturalization Act