Transcription

33Diagnosis and Management of Extra-articularCauses of Pain After Total Knee ArthroplastyBlaine T. Manning, BSNatasha Lewis, MDTony H. Tzeng, BSJamal K. Saleh, BSAnish G.R. Potty, MDDouglas A. Dennis, MDWilliam M. Mihalko, MD, PhDStuart B. Goodman, MD, PhDKhaled J. Saleh, MD, MSc, FRCSC, MHCMAbstractPostoperative pain, which has been attributed to poor outcomes after total knee arthroplasty (TKA), remains problematic for manypatients. Although the source of TKA pain can often be delineated, establishing a precise diagnosis can be challenging. It is often classified as intra-articular or extra-articular pain, depending on etiolog y. After intra-articular causes, such as instability, aseptic loosening,infection, or osteolysis, have been ruled out, extra-articular sources of pain should be considered. Physical examination of the other jointsmay reveal sources of localized knee pain, including diseases of the spine, hip, foot, and ankle. Additional extra-articular pathologiesthat have potential to instigate pain after TKA include vascular pathologies, tendinitis, bursitis, and iliotibial band friction syndrome.Patients with medical comorbidities, such as metabolic bone disease and psychological illness, may also experience prolonged postoperativepain. By better understanding the diagnosis and treatment options for extra-articular causes of pain after TKA, orthopaedic surgeonsmay better treat patients with this potentially debilitating complication.Instr Course Lect 2015;64:381–388.By 2030, the demand for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the United Statesis expected to quadruple from currentlevels to nearly 3.5 million proceduresannually.1 Although the safety andefficacy of TKA is well known, postoperative pain remains problematicand has been attributed to most pooroutcomes after TKA.2 Recent reportssuggest that 11% to 25% of patientstreated with TKA are dissatisfied withtheir postoperative outcomes, largelybecause of pain.3 A study by Puolakkaet al4 found that 36% of TKA patientsreported daily pain. Hawker et al5 reported similar fi ndings in patientstreated with TKA at 2 to 7 yearspostoperatively. 2015 AAOS Instructional Course Lectures, Volume 64There is a lack of consensus regarding the effect of age and sex on painafter TKA. Although certain studieshave cited female sex and younger ageas important predictors of postoperative pain, other research, includingthe 2003 National Institutes of Healthconsensus statement, reported a lackof correlation between age, sex, and381

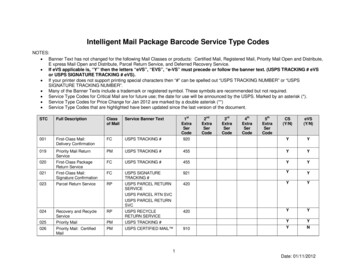

Adult Reconstruction: KneeTable 1Potential Sources of Postoperative Pain After TotalKnee nHip diseaseCrystalline diseaseFoot and ankle diseaseInstabilityNeurologic/spine diseaseComponent malalignmentTendinitis/bursitisLimb malalignmentIliotibial band syndromeAseptic looseningPsychological factorsSoft-tissue irritationHeterotopic ossificationComponent wearConnective tissue disordersOsteolysisMaterial hypersensitivityExtensor mechanism pathologyUnexplained painRecurrent hemarthrosispain after TKA.6-14 Younger patientsare known to have greater expectationsfor improved performance after TKA;however, the effects of these expectations and higher postoperative activitylevels and the lower expectations ofolder patients remain unclear.2Regardless of a patient’s risk factors,the diagnosis of an aseptic, painfulTKA may be confounded by a myriadof potential intra- and extra-articularcauses (Table 1). If preoperativesymptoms are not relieved by TKA,extra-articular etiologies should be investigated. Ruling out infection shouldbe the first step in diagnosing the sourceof postoperative pain after TKA, andthe clinical practice guidelines on thistopic from the American Academy ofOrthopaedic Surgeons can help directthe evaluation.15 Obtaining a thoroughhistory may aid in distinguishing between intra- and extra-articular painsources, because a lack of pain reliefimmediately after TKA could suggestthat the initial pain was not attributableto knee pathology. Additional symptoms, including delayed onset of postoperative pain, a sharp catching painduring movement, joint instability,or an abnormal radiographic finding,may indicate intra-articular causes. Anintra-articular injection of a local anesthetic also can be used to rule out anintra-articular source of pain.Hip DiseasePain can be referred from the hip tothe knee via the obturator and femoral nerves originating from L2-L4.16Immunohistochemistry staining hasbeen used to demonstrate the locationof referred pain from the hip joint, andfluoroscopically guided diagnostic hipinjections have been used to map patterns of referred pain to the knee.16,17Mechanical knee pain can result fromincreased knee torque resulting fromdecreased hip rotation or altered gaitfrom various diseases affecting the hipjoint. Patients with severe hip osteoarthritis who are awaiting hip arthroplasty may have pain that is localizedto the anterior and posterior aspects ofthe knee. Several studies have demonstrated the association between variousMr. Manning or an immediate family member serves as a paid consultant to or is an employee of the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine. Mr. J. Saleh or an immediate familymember has received royalties from Aesculap/B. Braun; is a member of a speakers’ bureau or has made paid presentations on behalf of Carefusion; serves as a paid consultant to or isan employee of Aesculap/B. Braun and Watermark; has received research or institutional support from Smith & Nephew and the National Institutes of Health/National Instituteof Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Skin Diseases; and serves as a board member, owner, officer, or committee member of the American Orthopaedic Association, the American Board ofOrthopaedic Surgery, and Blue Cross Blue Shield. Dr. Dennis or an immediate family member has received royalties from DePuy and Innomed; is a member of a speakers’ bureau or hasmade paid presentations on behalf of DePuy; serves as a paid consultant to or is an employee of DePuy; has stock or stock options held in Joint Vue; has received research or institutionalsupport from DePuy and Porter Adventist Hospital; and serves as a board member, owner, officer, or committee member of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, the HipSociety, Joint Vue, the International Congress for Joint Reconstruction, and Operation Walk USA. Dr. Mihalko or an immediate family member has received royalties from Aesculap/B.Braun; is a member of a speakers’ bureau or has made paid presentations on behalf of Aesculap/B. Braun; serves as a paid consultant to or is an employee of Aesculap/B. Braun andMedtronic; has received research or institutional support from Aesculap/B. Braun; and serves as a board member, owner, officer, or committee member of the American OrthopaedicAssociation and ASTM International. Dr. Goodman or an immediate family member serves as an unpaid consultant to Accelalox, Biomimedica, and Tibion; has stock or stock optionsheld in Accelalox, Biomimedica, StemCor, and Tibion; has received research or institutional support from Baxter; and serves as a board member, owner, officer, or committee member ofthe American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Biological Implants Committee. Dr. Saleh or an immediate family member has received royalties from Aesculap/B. Braun; serves as apaid consultant to or is an employee of Southern Illinois University School of Medicine Division of Orthopaedics, Aesculap, the Memorial Medical Center Co-Management OrthopaedicBoard, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Blue Ribbon Panel, Watermark, Stryker, and the Exactech Data Safety Monitoring Board; has received research or institutional support from Smith& Nephew, the Orthopaedic Research and Educational Foundation, National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Skin Diseases (R0-1); andserves as a board member, owner, officer, or committee member of the American Orthopaedic Association Finance Committee, the Orthopaedic Research and Education FoundationIndustry Relations Committee, the Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation Clinical Research Awards Committee, and the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Noneof the following authors nor any immediate family member has received anything of value from or has stock or stock options held in a commercial company or institution related directly orindirectly to the subject of this chapter: Dr. Lewis, Mr. Tzeng, and Dr. Potty.382 2015 AAOS Instructional Course Lectures, Volume 64

Diagnosis and Management of Extra-articular Causes of Pain After Total Knee Arthroplastyforms of hip disease, including osteoarthritis, infection, hip fracture, andposterior hip dislocation, with ipsilateral knee pain.18-21 Other sources of hipdisease, such as osteonecrosis, dysplasia,and implant loosening after total hiparthroplasty, can present as knee pain.Stress fractures, including femoral neck,pubic, and subtrochanteric stress fractures, are rare complications after TKAin patients with poor bone quality butcan be secondary causes of pain.22-26Generally, all patients who present withknee pain should have a physical examination of the ipsilateral hip to screenfor pathology. If a painful or decreasedrange of hip motion is noted after TKA,radiographic studies are recommended.Foot and Ankle DiseaseMalalignment of the hindfoot resulting in excess valgus alignment ofthe heel secondary to posterior tibial tendon insufficiency or pes planusincreases stress forces on the knee.27This hindfoot valgus leads to increasedlateral loading of the knee because ofchanges in ground reactive forces andan increased valgus thrust.28 Bhaveet al29 reported that patients with planovalgus malalignment had substantial postoperative pain relief with shoemodifications. In addition to a physicalexamination, screening for malalignment of the hindfoot and ankle alsocan be performed during radiographicmeasurement of the weight-bearingaxis. Numerous studies have noted theefficacy of including the hindfoot distal to the ankle and subtalar joint in anassessment of the ground mechanicalaxis deviation.27,28,30,31 A comprehensiveradiographic evaluation of the rearfoot,ankle, and leg taken in multiple planesand angles may be appropriate beforeTKA in select patients and can beuseful in ruling out foot and ankle-related etiologies in patients with painafter TKA.Vascular DiseaseVascular diseases, such as lower extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD) orthrombosis, also have potential to contribute to symptoms of leg pain and arecommon in older patients. Although often useful as indicators for PAD, neitherthe presence of known risk factors (suchas hyperlipidemia, cardiac disease, anddiabetes) nor symptoms of claudicationare definitive predictors of PAD.32,33 Ina study of 50 consecutive patients referred to an orthopaedic surgeon for legpain, Bernstein et al34 noted that 20%had undiagnosed PAD. Assessing forPAD via pulse volume recording orankle-brachial pulse indexing (an indexof 0.9 may indicate PAD) is neitherinvasive nor costly, especially given thefrequency of PAD in patients without ahistory of trauma or claudication whopresent with leg pain.34Indirect injury to arteries via compression can occur during TKA as external forces applied to diseased vesselsduring tourniquet application can leadto vascular damage, plaque disruption,and subsequent thrombus formation.Thrombosis is one of the most common causes of vascular insufficiencyafter TKA and can be confirmed withDoppler imaging secondary to a positive Homan sign.35 If an extra-articularsource of pain after TKA is suspected,the presence of vascular diseases shouldbe investigated.Lumbar Spine andNeurologic DisordersLumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) has anincidence as high as 8% and is a common cause of leg pain in older adults.36 2015 AAOS Instructional Course Lectures, Volume 64Chapter 33Nevertheless, patients with LSS whoundergo TKA have been shown tohave comparable outcomes to controlpatients with regard to revision ratesand radiographic outcomes despite theirlower preoperative functional scores.37LSS is often idiopathic and presentsas intermittent neurogenic claudication caused by the compression of thecauda equina, which results from enlargement of the bony and soft tissuesassociated with the spinal canal. In astudy of 100 patients, Amundsen et al38reported additional common symptomsof back pain, leg pain, weakness, andvoiding disturbances. Double nerveroot involvement is typical, and theL5 nerve root is the most commonlyaffected (prevalence of 91%), followedby S1 (63%), L1-4 (28%), and S2-5 (5%).In patients with suspected LSS, athorough physical examination shouldbe conducted to rule out any otherpathology that may be the source ofreferred pain to the legs. Sensory examination should include vibration,proprioception, and pin-prick testingin the appropriate nerve distributionregions. Loss of tendon reflexes, sciaticnotch tenderness, and reduced lumbarlordosis may also be present in patientswith suspected LSS. Motor weaknesstypically presents in the L5 nerve distribution. Amundsen et al38 reportedsensory changes in 51% of patientswith LSS, reflex changes in 47%, lumbar tenderness in 40%, reduced spinalmobility in 36%, a positive straightleg–raising test in 24%, weakness in23%, and perianal numbness in 6%. Ifa clinical diagnosis of LSS is indicated,imaging studies should be used for confirmation. Upright plain radiographs areuseful for excluding other spine pathologies, and CT and MRI can confirmnerve compression.38383

Adult Reconstruction: KneeOther neurologic disorders, suchas complex regional pain syndrome(CRPS) and cutaneous neuroma, alsohave the potential to contribute to theincidence of pain after TKA. Previously referred to as reflex sympatheticdystrophy, CRPS symptoms includecutaneous hypersensitivity, abnormalskin color, edema, motor function impairment, and abnormal sudomotor activity.39,40 The occurrence of CRPS afterTKA is rare; a diagnosis of CRPS wasmade in only 5 of 662 patients (0.8%)in a recent series.41 As a testament tothe elusiveness of a CRPS diagnosis,the mean diagnostic time in this patientgroup was 5 months postoperatively.Although the pathophysiologicmechanisms of CRPS remain unclear,the condition is thought to be initiated by sensitization of nociceptivenerve fibers by trauma.42,43 Regardlessof etiology, the diagnosis of CRPS often consists of excluding other painfulconditions. A variety of tests, including infrared thermography, quantitative sensory testing, sudomotor testing,and bone scintigraphy, can be used torule out other painful conditions anddifferentiate CRPS. In TKA patientswith suspected CRPS, orthopaedicdisorders with CRPS-like symptoms(such as rheumatic arthritis, tendoninfection, or migratory osteoporosis)should be ruled out first. Treatment ofCRPS typically centers on therapeuticinterventions. Sympathetic blockadeby an anesthesiologist, electrotherapy,occupational therapy, physical therapy,and proper counseling are often necessary in managing patients with CRPS.Cutaneous and subcutaneous neuromas are another rare neurosensorydisorder that can cause pain after TKAand are often diagnosed by injectinglidocaine into the suspected neuroma384site. Pain relief is often a confirmationof a cutaneous neuroma, which can besubsequently treated with a variety ofnonsurgical interventions such as localanesthetics or spinal cord stimulation.If nonsurgical measures prove unsuccessful, cutaneous nerve resection maybe warranted.41,44 In a series of patientswho received a diagnosis of cutaneousneuroma after TKA, Katz and Hungerford41 found that 87% reportedsubstantial improvement in visualanalog scale pain scores after sympathetic blockade or sympathectomy byan anesthesiologist.Tendinitis, Bursitis, andIliotibial Band SyndromePosterolateral knee pain after TKA canarise from a variety of sources. Pandheret al45 reported a case of biceps tendinitis as the etiology of an acutely painful knee after TKA. Inflammation ofthe popliteus tendon also can presentwith posterolateral knee pain secondaryto irritation from a laterally displacedfemoral component, retained posterolateral osteophyte or cementophyte,or posterolateral tibial tray overhang.Alternatively, quadriceps and patellartendinitis will present with anteriorknee pain and typically result from atraumatic or overuse injury.Semimembranosus tendinitis hasbeen reported as a source of pain afterTKA.46 It typically presents as pain inthe posteromedial knee that radiates intothe posterior thigh or calf region andworsens in deep knee flexion. Physicalexamination findings typically consist oftenderness to palpation at the semimembranosus tibial insertion and increasedpain during passive deep flexion. MRIis useful in confirming the diagnosis.Surrounding the knee are multiple periarticular bursae (prepatellar,infrapatellar, pes anserine, and semimembranosus) that can become acutelyinflamed and lead to knee pain (Figure 1). The occurrence of a poplitealcyst is commonly associated with kneearthritis or meniscal injury and is usually secondary to inflammation of thesemimembranosus bursa. Rauschning47showed evidence of a defect in theposteromedial capsule that communicated with the semimembranosus bursa,displacing the semimembranosus andgastrocnemius tendons in 46% of thecadavers with no previous history ofknee surgery or disease. Inflammationof the semimembranosus bursa via anintra-articular communication typicallypresents as a classic Baker cyst (Figure 2). Huang et al48 reported a rarecase of foreign body–mediated chronicpes anserinus bursitis induced by polyethylene particles that caused pain,swelling, and drainage.Iliotibial band traction/frictionsyndrome should be considered in patients with a painful range of motion(specifically between 20 to 80 ) andwith pain localized to the lateral femoral epicondylar region.49,50 Luyckx etal49 reported a 7.2% incidence of iliotibial band traction/friction syndromein a cruciate-substituting TKA design.The increased incidence was attributed to excessive lateral femoral condyletranslation and internal rotation of thetibia, leading to excessive tension on theiliotibial band. This syndrome can beelicited using the Ober, Thomas, andNoble tests, and it typically presents asan overuse injury in conjunction withincreased iliotibial band tightness.51 AnOber test is conducted with the patientlying on his or her side. After flexionof the knee to 90 and extension andabduction of the affected hip by the examiner, support of the knee is released. 2015 AAOS Instructional Course Lectures, Volume 64

Diagnosis and Management of Extra-articular Causes of Pain After Total Knee ArthroplastyChapter 33Figure 2 MRI demonstratinginflammation of the semimembranosus bursa and subsequent Bakercyst formation (arrow).Figure 1Illustration of some of the prominent knee bursae.Failure of the hip to adduct indicates apositive test. The Thomas test is conducted with the patient supine. After theexaminer places his or her hand underthe lumbar spine to prevent hyperlordosis, the unaffected hip and knee are fullyflexed. The patient holds the knee. Apositive sign is indicated by the affectedleg raising off the table. Both legs canthen be fully flexed, and the affected legis slowly lowered back into extension.A lack of full extension may indicateiliopsoas tightness, and any externalrotation may suggest iliotibial bandtightness. With the patient supine, theNoble test is conducted by flexing theaffected hip and knee to 90 and placingpressure on the lateral femoral epicondyle with the thumb. With continuingpressure, the leg is passively and slowlyextended. A positive test is indicated bythe presence of pain at 30 of flexion.Many cases of iliotibial band traction/friction syndrome resolve withnonsurgical treatments, includinganti-inflammatory medications or local steroid injections. If pain persists,surgical release of the iliotibial bandmay be necessary.Heterotopic OssificationOxidative stress from hypoxic environments often induces production of mastcells and fibroblast growth factor, whichin turn undergo metaplastic transformation and leads to fibrocartilage formation with subsequent endochondralossification and bone formation.52 Heterotopic ossification can be asymptomatic or associated with a loss of motionin addition to catching and snappingthat is localized to the patellofemoraljoint. The incidence of heterotopic ossification varies widely, with an increasedincidence in heavier patients, men, andpatients with larger preoperative deformities.53 Patients at elevated risk forheterotopic ossification include thosewith previous heterotropic ossification,bilateral hypertrophic osteoarthritis,and posttraumatic osteoarthritis withhypertrophic osteophytosis.54,55Radiographs and laboratory testingare rarely helpful in detecting early 2015 AAOS Instructional Course Lectures, Volume 64stages of heterotopic ossification because calcium deposition in the bonematrix and developmental alkalinephosphatase elevation do not occuruntil several weeks after the initial onset of heterotopic ossification. Bonescanning may be useful for a definitive diagnosis and is known to detectheterotopic ossification earlier thanradiographs or laboratory testing.56Either a NSAID (such as indomethacin), diphosphonate (such as ethane1-hydroxy-1,1-diphosphate), or localradiation therapy is recommended forthe treatment or prophylaxis of heterotopic ossification.57Fibromyalgia and ConnectiveTissue DisordersAlthough the precise source of painin fibromyalgia remains unknown, itclearly depends on peripheral nociceptive input as well as abnormal centralpain processing.58 Some studies havesuggested soft-tissue inflammation asthe source of pain in fibromyalgia because pain and weakness of the musclesis one of its main symptoms. Changes385

Adult Reconstruction: Kneeindicating disturbed microcirculation,mitochondrial damage, and a reductionin high-energy phosphates all suggestan energy-deficient state in the resting, painful muscles of patients withfibromyalgia.59 Although fibromyalgia ischaracterized by allodynia and chronicpain, it should not be considered a contraindication for TKA because patientswith fibromyalgia have shown improvement similar to that of control patientsafter TKA.60,61 Nevertheless, thesepatients have reported lower postoperative satisfaction, largely because ofhigher levels of persistent postoperativepain.60,61 The criteria set forth by theAmerican College of Rheumatology areuseful in diagnosing fibromyalgia; treatment typically consists of medicationsor therapy.62Rarer connective tissue disorders,such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, alsohave potential to cause chronic pain inTKA patients. Deficiencies of collagen production in TKA patients withEhlers-Danlos syndrome has beenshown to instigate pain via degeneration and destabilization of the kneejoint.63 In a case series of 10 TKA patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome,approximately 30% reported dissatisfaction with TKA because of continuedpain and instability.64 Although rare, adiagnosis of Ehlers-Danlos syndromeshould be confirmed through genetictesting and treated with a combinationof physical therapy and pain-relievingand anti-inflammatory medications.Psychological Factors andPain CatastrophizingThe potential for psychological factorsto influence a patient’s perceptions ofpain after TKA is well known, because pain catastrophizing has beendesignated a consistent and powerful386psychological predictor of poor outcomes after TKA.65,66 Patients whocatastrophize about their pain ruminatemore often about their pain, magnifyits perceived threat, and experiencegreater feelings of helplessness whendealing with pain. Patients with higherpreoperative pain and anxiety levelstypically report extended postoperativeTKA pain and diminished function.11It is imperative to carefully monitorand, if necessary, refer for further psychological treatment patients who mayexperience diminished postoperativeoutcomes because of anxiety, catastrophizing, or other psychological maladies known to intensify pain.Metal HypersensitivityThere is a paucity of clinical studiescorrelating positive hypersensitivityresults with clinical TKA outcomes.67,68Nevertheless, metal hypersensitivity hasbeen described previously as a type IVimmunologic reaction and also may beconsidered as an unlikely cause for apainful TKA if all other causes havebeen ruled out.69 Hypersensitivity reactions typically occur in the periprosthetic region in the months after TKA.Although rarely used, in vitro proliferation testing via lymphocyte transformation testing may be useful in assessingsensitivity to metal implants. Lymphocyte transformation testing consists ofmeasuring lymphocyte proliferationafter activation in vitro and comparing the findings with in vivo levels.Skin patch testing for nickel, cobalt, orchromium reaction may also be usefulin detecting metal hypersensitivity inTKA patients, although the correlation between a positive test and symptom presentation remains unclear.3,70Hypoallergenic implants (specificallythose that do not contain nickel) arewarranted in a select subset of susceptible patients.SummaryDetermining the cause of pain afterTKA can be a challenging task for anorthopaedic surgeon. With a thoroughpatient history, examination, and appropriate diagnostic approach, mostsources of pain can be identified. Aftersepsis and intra-articular causes havebeen ruled out, extra-articular sourcesshould be investigated. If the sourceof pain cannot be identified, revisionarthroplasty alone is unlikely to relievesymptoms. By establishing an accurateetiology in a timely manner, unnecessary diagnostic testing will be avoidedand the patient can be appropriatelytreated.References1. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F,Halpern M: Projections of primaryand revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am2007;89(4):780-785.2. Fehring TK, Odum S, Griffin WL,Mason JB, Nadaud M: Early failuresin total knee arthroplasty. Clin OrthopRelat Res 2001;392:315-318.3. Seil R, Pape D: Causes of failure andetiology of painful primary total kneearthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports TraumatolArthrosc 2011;19(9):1418-1432.4. Puolakka PA, Rorarius MG, RoviolaM, Puolakka TJ, Nordhausen K,Lindgren L: Persistent pain followingknee arthroplasty. Eur J Anaesthesiol2010;27(5):455-460.5. Hawker GA, Stewart L, French MR,et al: Understanding the pain experience in hip and knee osteoarthritis:An OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16(4):415-422.6. Singh JA, Gabriel S, Lewallen D:The impact of gender, age, andpreoperative pain severity on painafter TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res2008;466(11):2717-2723. 2015 AAOS Instructional Course Lectures, Volume 64

Diagnosis and Management of Extra-articular Causes of Pain After Total Knee Arthroplasty7. Elson DW, Brenkel IJ: Predicting painafter total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2006;21(7):1047-1053.8. Fitzgerald JD, Orav EJ, Lee TH,et al: Patient quality of life duringthe 12 months following jointreplacement surgery. Arthritis Rheum2004;51(1):100-109.9. Lingard EA, Katz JN, Wright EA,Sledge CB; Kinemax OutcomesGroup: Predicting the outcome oftotal knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint SurgAm 2004;86(10):2179-2186.17. Lesher JM, Dreyfuss P, Hager N,Kaplan M, Furman M: Hip joint painreferral patterns: A descriptive study.Pain Med 2008;9(1):22-25.18. Crawford RW, Gie GA, Ling RS,Murray DW: Diagnostic value ofintra-articular anaesthetic in primaryosteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone JointSurg Br 1998;80(2):279-281.19. Emms NW, O’Connor M, Montgomery SC: Hip pathology can masquerade as knee pain in adults. AgeAgeing 2002;31(1):67-69.10. March LM, Cross MJ, Lapsley H,et al: Outcomes after hip or kneereplacement surgery for osteoarthritis: A prospective cohort studycomparing patients’ quality of lifebefore and after surgery with agerelated population norms. Med J Aust1999;171(5):235-238.20. Hammer SG: Hip fracture presentingas knee pain in an elderly patient. AmFam Physician 1996;54(3):872.11. Brander VA, Stulberg SD, Adams AD,et al: Predicting total knee replacement pain: A prospective, observational study. Clin Orthop Relat Res2003;416:27-36.22. Tharani R, Nakasone C, VinceKG: Periprosthetic fractures aftertotal knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty2005;20(4, suppl 2):27-32.12. Fortin PR, Clarke AE, Joseph L,et al: Outcomes of total hip and kneereplacement: Preoperative functional status predicts outcomes at sixmonths after surgery. Arthritis Rheum1999;42(8):1722-1728.13. Jones CA, Voaklander DC, JohnstonDW, Suarez-Almazor ME: Theeffect of age on pain, function, andquality of life after total hip andknee arthroplasty. Arch Intern Med2001;161(3):454-460.14. Roth ML, Tripp DA, Harrison MH,Sullivan M, Carson P: Demographicand psychosocial predictors ofacute perioperative pain for totalknee arthroplasty. Pain Res Manag2007;12(3):185-194.15. Parvizi J, Della Valle CJ: AAOSClinical Practice Guideline: Diagnosisand treatment of periprosthetic jointinfections of the hip and knee. J AmAcad Orthop Surg 2010;18(12):771-772.16. Takeshita M, Nakamura J, Ohtori S, etal: Sensory innervation and inflammatory cytokines in hypertrophic synoviaassociated with pain transmission inosteoarthritis of the hip: A casecontrol study. Rheumatolog y (Oxford)2012;51(10):1790-1795.21. Hetsroni I, Weigl D: Referredknee pain in posterior dislocation of the hip. Clin Pediatr (Phila)2006;45(1):93-95.23. Smith MD, Henke JA: Pubic ramusfatigue fractures after total kneearthroplasty: A case report. Orthopedics1988;11(2):315-317.24. Torisu T: Fatigue fracture of thepelvis after total knee replacements:Report of a case. Clin Orthop Relat Res1980;149:216-219.25. Palance Martin D, Albareda J, Seral F:Subcapital stress fracture of the femoral neck after total knee arthroplasty.Int Orthop 1994;18(5):308-309.26. Lesniewski PJ, Testa NN: Stress fracture of the hip as a co

By 2030, the demand for total knee ar-throplasty (TKA) in the United States is expected to quadruple from current levels to nearly 3.5 million procedures annually.1 Although the safety and effi cacy of TKA is well known, post-operative pain remains problematic and has been attributed to most poor outcomes after TKA.2 Recent reports suggest that 11% to 25% of patients treated with TKA are .