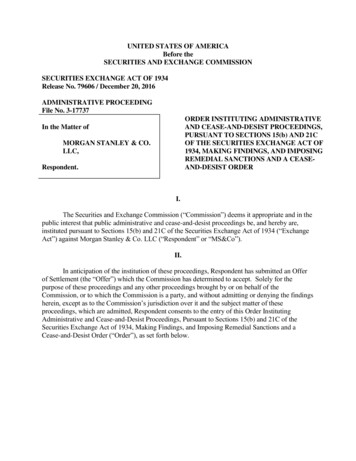

Transcription

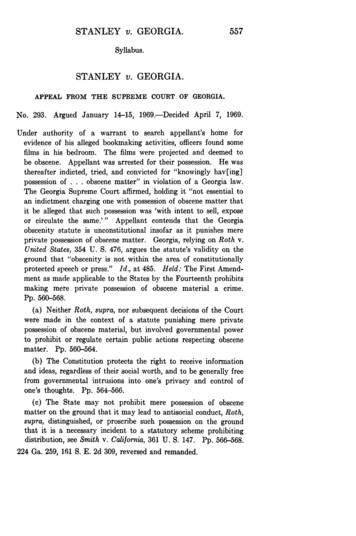

STANLEY v. GEORGIA.Syllabus.STANLEY v. GEORGIA.APPEAL FROM THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA.No. 293.Argued January 14-15, 1969.-Decided April 7, 1969.Under authority of a warrant to search appellant's home forevidence of his alleged bookmaking activities, officers found somefilms in his bedroom. The films were projected and deemed tobe obscene. Appellant was arrested for their possession. He wasthereafter indicted, tried, and convicted for "knowingly hav[ing]possession of . . . obscene matter" in violation of a Georgia law.The Georgia Supreme Court affirmed, holding it "not essential toan indictment charging one with possession of obscene matter thatit be alleged that such possession was 'with intent to sell, exposeor circulate the same.' " Appellant contends that the Georgiaobscenity statute is unconstitutional insofar as it punishes mereprivate possession of obscene matter. Georgia, relying on Roth v.United States, 354 U. S. 476, argues the statute's validity on theground that "obscenity is not within the area of constitutionallyprotected speech or press." Id., at 485. Held: The First Amendment as made applicable to the States by the Fourteenth prohibitsmaking mere private possession of obscene material a crime.Pp. 560-568.(a) Neither Roth, supra, nor subsequent decisions of the Courtwere made in the context of a statute punishing mere privatepossession of obscene material, but involved governmental powerto prohibit or regulate certain public actions respecting obscenematter. Pp. 560-564.(b) The Constitution protects the right to receive informationand ideas, regardless of their social worth, and to be generally freefrom governmental intrusions into one's privacy and control ofone's thoughts. Pp. 564-566.(c) The State may not prohibit mere possession of obscenematter on the ground that it may lead to antisocial conduct, Roth,supra, distinguished, or proscribe such possession on the groundthat it is a necessary incident to a statutory scheme prohibitingdistribution, see Smith v. California,361 U. S. 147. Pp. 566-568.224 Ga. 259, 161 S. E. 2d 309, reversed and remanded.

OCTOBER TERM, 1968.Opinion of the Court.394 U. S.Wesley R. Asinof argued the cause and filed a brief forappellant.J. Robert Sparks argued the cause for appellee.him on the brief was Lewis R. Slaton.WithMR. JUSTICE MARSHALL delivered the opinion of theCourt.An investigation of appellant's alleged bookmakingactivities led to the issuance of a search warrant forappellant's home. Under authority of this warrant,federal and state agents secured entrance. They foundvery little evidence of bookmaking activity, but whilelooking through a desk drawer in an upstairs bedroom, one of the federal agents, accompanied by astate officer, found three reels of eight-millimeter film.Using a projector and screen found in an upstairsliving room, they viewed the films. The state officerconcluded that they were obscene and seized them.Since a further examination of the bedroom indicatedthat appellant occupied it, he was charged with possessionof obscene matter and placed under arrest. He waslater indicted for "knowingly havi[ing] possession of . .obscene matter" in violation of Georgia law.1 Appel-' "Any person who shall knowingly bring or cause to be broughtinto this State for sale or exhibition, or who shall knowingly sell oroffer to sell, or who shall knowingly lend or give away or offer tolend or give away, or who shall knowingly have possession of, or whoshall knowingly exhibit or transmit to another, any obscene matter,or who shall knowingly advertise for sale by any form of notice,printed, written, or verbal, any obscene matter, or who shall knowingly manufacture, draw, duplicate or print any obscene matter withintent to sell, expose or circulate the same, shall, if such person hasknowledge or reasonably should know of the obscene nature of suchmatter, be guilty of a felony, and, upon conviction thereof, shall bepunished by confinement in the penitentiary for not less than oneyear nor more than five years: Provided, however, in the event the

STANLEY v. GEORGIA.557Opinion of the Court.lant was tried before a jury and convicted. The SupremeCourt of Georgia affirmed. Stanley v. State, 224 Ga.259, 161 S. E. 2d 309 (1968). We noted probable jurisdiction of an appeal brought under 28 U. S. C. § 1257 (2).393 U. S. 819 (1968).Appellant raises several challenges to the validity ofhis conviction.2 We find it necessary to consider onlyone. Appellant argues here, and argued below, thatthe Georgia obscenity statute, insofar as it punishes mereprivate possession of obscene matter, violates the FirstAmendment, as made applicable to the States by theFourteenth Amendment. For reasons set forth below,we agree that the mere private possession of obscenematter cannot constitutionally be made a crime.The court below saw no valid constitutional objectionto the Georgia statute, even though it extends furtherthan the typical statute forbidding commercial sales ofobscene material. It held that "[i]t is not essential toan indictment charging one with possession of obscenematter that it be alleged that such possession was 'withintent to sell, expose or circulate the same.'" Stanleyv. State, supra, at 261, 161 S. E. 2d, at 311. TheState and appellant both agree that the question herebefore us is whether "a statute imposing criminal sanctions upon the mere [knowing] possession of obscenematter" is constitutional. In this context, Georgia concedes that the present case appears to be one of "firstjury so recommends, such person may be punished as for a misdemeanor. As used herein, a matter is obscene if, considered as awhole, applying contemporary community standards, its predominant appeal is to prurient interest, i. e., a shameful or morbid interestin nudity, sex or excretion." Ga. Code Ann. § 26-6301 (Supp. 1968).2 Appellant does not argue that the films are not obscene.Forthe purpose of this opinion, we assume that they are obscene underany of the tests advanced by members of this Court. See Redrup v.New York, 386 U. S. 767 (1967).

OCTOBER TERM, 1968.Opinion of the Court.394 U. S.impression . on this exact point," but contends thatsince "obscenity is not within the area of constitutionallyprotected speech or press," Roth v. United States, 354U. S. 476, 485 (1957), the States are free, subject to thelimits of other provisions of the Constitution, see, e. g.,Ginsberg v. New York, 390 U. S. 629, 637-645 (1968), todeal with it any way deemed necessary, just as they maydeal with possession of other things thought to bedetrimental to the welfare of their citizens. If the Statecan protect the body of a citizen, may it not, arguesGeorgia, protect his mind?It is true that Roth does declare, seemingly withoutqualification, that obscenity is not protected by theFirst Amendment. That statement has been repeated invarious forms in subsequent cases. See, e. g., Smith v.California,361 U. S. 147, 152 (1959); Jacobellis v. Ohio,378 U. S. 184, 186-187 (1964) (opinion of BRENNAN, J.) ;Ginsberg v. New York, supra, at 635. However, neitherRoth nor any subsequent decision of this Court dealtwith the precise problem involved in the present case.Roth was convicted of mailing obscene circulars andadvertising, and an obscene book, in violation of afederal obscenity statute.4 The defendant in a companion case, Alberts v. California,354 U. S. 476 (1957),was convicted of "lewdly keeping for sale obscene and indecent books, and [of] writing, composing and publishing an obscene advertisement of them . . . ." Id.,at 481. None of the statements cited by the Court in3The issue was before the Court in Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643(1961), but that case was decided on other grounds. MR. JUSTICESTEWART, although disagreeing with the majority opinion in Mapp,would have reversed the judgment in that case on the ground thatthe Ohio statute proscribing mere possession of obscene material was"not 'consistent with the rights of free thought and expressionassured against state action by the Fourteenth Amendment.'" Id.,at 672.- 18 U. S. C. § 1461.

STANLEY v. GEORGIA.557Opinion of the Court.Roth for the proposition that "this Court has alwaysassumed that obscenity is not protected by the freedomsof speech and press" were made in the context of astatute punishing mere private possession of obscenematerial; the cases cited deal for the most part withuse of the mails to distribute objectionable material orwith some form of public distribution or dissemination.5Moreover, none of this Court's decisions subsequent toRoth involved prosecution for private possession ofobscene materials. Those cases dealt with the power ofthe State and Federal Governments to prohibit or regulate certain public actions taken or intended to be takenwith respect to obscene matter.6 Indeed, with one5Ex parte Jackson, 96 U. S. 727, 736-737 (1878)(use of themails); United States v. Chase, 135 U. S.255, 261 (1890) (use ofthe mails); Robertson v. Baldwin, 165 U. S. 275, 281 (1897) (publication) ; Public Clearing House v. Coyne, 194 U. S. 497, 508 (1904)(use of the mails); Hoke v. United States, 227 U. S.308, 322 (1913)(use of interstate facilities); Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S.697, 716(1931) (publication); Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568,571-572 (1942) (utterances); Hannegan v. Esquire, Inc., 327 U. S.146, 158 (1946) (use of the mails); Winters v. New York, 333 U. S.507, 510 (1948) (possession with intent to sell); Beauharnais v.Illinois, 343 U. S. 250, 266 (1952) (libel).6 Many of the cases involved prosecutions for sale or distributionof obscene materials or possession with intent to sell or distribute.See Redrup v. New York, 386 U. S.767 (1967); Mishkin v. NewYork, 383 U. S.502 (1966); Ginzburg v. United States, 383 U. S.463 (1966); Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U. S. 184 (1964); Smith v.California, 361 U. S. 147 (1959). Our most recent decision involved a prosecution for sale of obscene material to children. Ginsberg v. New York, 390 U. S. 629 (1968); cf. Interstate Circuit, Inc.v. City of Dallas, 390 U. S. 676 (1968). Other cases involvedfederal or state statutory procedures for preventing the distribution or mailing of obscene material, or procedures for predistributionapproval. See Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U. S. 51 (1965);Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 58 (1963); ManualEnterprises, Inc. v. Day, 370 U. S.478 (1962). Still another casedealt with an attempt to seize obscene material "kept for the purpose

OCTOBER TERM, 1968.Opinion of the Court.394 U. S.exception, we have been unable to discover any case inwhich the issue in the present case has been fullyconsideredof being sold, published, exhibited . .or otherwise distributed orcirculated . . ."Marcus v. Search Warrant, 367 U. S. 717, 719(1961); see also A Quantity of Books v. Kansas, 378 U. S.205 (1964).Memoirs v. Massachusetts, 383 U. S. 413 (1966), was a proceedingin equity against a book. However, possession of a book determinedto be obscene in such a proceeding was made criminal only when"for the purpose of sale, loan or distribution." Id., at 422.1The Supreme Court of Ohio considered the issue in State v.Mapp, 170 Ohio St. 427, 166 N. E. 2d 387 (1960). Four of theseven judges of that court felt that criminal prosecution for mereprivate possession of obscene materials was prohibited by the Constitution. However, Ohio law required the concurrence of "all butone of the judges" to declare a state law unconstitutional. The viewof the "dissenting" judges was expressed by Judge Herbert:"I cannot agree that mere private possession of . . [obscene] lit-erature by an adult should constitute a crime. The right of theindividual to read, to believe or disbelieve, and to think withoutgovernmental supervision is one of our basic liberties, but to dictateto the mature adult what books he may have in his own privatelibrary seems to the writer to be a clear infringement of his constitutional rights as an individual." 170 Ohio St., at 437, 166 N. E.2d, at 393.Shortly thereafter, the Supreme Court of Ohio interpreted theOhio statute to require proof of "possession and control for thepurpose of circulation or exhibition." State v. Jacobelis, 173 OhioSt. 22, 27-28, 179 N. E. 2d 777, 781 (1962), rev'd on other grounds,378 U. S. 184 (1964). The interpretation was designed to avoidthe constitutional problem posed by the "dissenters" in Mapp. SeeState v. Ross, 12 Ohio St. 2d 37, 231 N. E. 2d 299 (1967).Other cases dealing with nonpublic distribution of obscene materialor with legitimate uses of obscene material have expressed similar reluctance to make such activity criminal, albeit largely on statutorygrounds. In United States v. Chase, 135 U. S.255 (1890), the Courtheld that federal law did not make criminal the mailing of a privatesealed obscene letter on the ground that the law's purpose was topurge the mails of obscene matter "as far as was consistent withthe rights reserved to the people, and with a due regard to thesecurity of private correspondence . . ."135 U. S., at 261.The

STANLEY v. GEORGIA.557Opinion of the Court.In this context, we do not believe that this case canbe decided simply by citing Roth. Roth and its progenycertainly do mean that the First and Fourteenth Amendments recognize a valid governmental interest in dealingwith the problem of obscenity. But the assertion ofthat interest cannot, in every context, be insulated fromall constitutional protections. Neither Roth nor anyother decision of this Court reaches that far. As theCourt said in Roth itself, "[c]easeless vigilance is thewatchword to prevent . . . erosion [of First Amendmentrights] by Congress or by the States. The door barringfederal and state intrusion into this area cannot be leftajar; it must be kept tightly closed and opened only theslightest crack necessary to prevent encroachment uponmore important interests." 354 U. S., at 488. Rothand the cases following it discerned such an "importantinterest" in the regulation o

STANLEY v. GEORGIA. 557 Opinion of the Court. lant was tried before a jury and convicted. The Supreme Court of Georgia affirmed. Stanley v. State, 224 Ga. 259, 161 S. E. 2d 309 (1968). We noted probable juris-diction of an appeal brought under 28 U. S. C. § 1257 (2). 393 U. S. 819 (1968).