Transcription

LIFE INLOCKDOWNChild and adolescent mental healthand well-being in the time of COVID-19

bLife in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-19EXECUTIVE SUMMARYUNICEF OFFICE OF RESEARCH - INNOCENTIThe Office of Research – Innocenti is UNICEF’s dedicated research centre. Itundertakes research on emerging or current issues to: inform the strategicdirection, policies and programmes of UNICEF and its partners; shape globaldebates on child rights and development; and inform the global researchand policy agenda for all children, particularly for the most vulnerable. Officeof Research – Innocenti publications are contributions to a global debateon children and may not necessarily reflect UNICEF policies or approaches.The Office of Research – Innocenti receives financial support from theGovernment of Italy, while funding for specific projects is also provided by othergovernments, international institutions and private sources, including UNICEFNational Committees.The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper are thoseof the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNICEF. This paper hasbeen peer reviewed both externally and within UNICEF.Any part of this publication may be freely reproduced if accompanied by thefollowing citation: Sharma, M., Idele, P., Manzini, A., Aladro, CP., Ipince, A.,Olsson, G., Banati, P., Anthony, D. Life in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mentalhealth and well-being in the time of COVID-19, UNICEF Office of Research –Innocenti, Florence, 2021.Requests to utilize larger portions or the full publication should be addressed tothe Communications Unit at: Florence@unicef.org.Correspondence should be addressed to:UNICEF Office of Research – InnocentiVia degli Alfani, 5850121 Florence, ItalyTel: ( 39) 055 20 330Fax: ( 39) 055 2033 220florence@unicef.orgwww.unicef-irc.orgtwitter: @UNICEFInnocentifacebook.com/UnicefInnocenti ️ United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2021Cover Photo: UNICEF/UNI362245/EverettA child studies his Class 6 textbooks. He cannot participate in online learning as hisfamily has no mobile phone. “This is a pandemic,” says his mother, “and the measures arenecessary, but a disaster for the kids.” Informal settlement of Mathare, Nairobi, Kenya, 2020.

LIFE INLOCKDOWN:Child and adolescentmental health and well-beingin the time of COVID-19

This study was conducted by the UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti,in Florence, Italy.STUDY TEAMStrategic conceptualization and technical oversight:Priscilla Idele, Prerna Banati and David AnthonyStrategic review:Gunilla OlssonResearch analysis and evidence synthesis:Manasi Sharma, Arianna Manzini, Camila Perera, Alessandra Ipince and Prerna BanatiEditorial and Communication support:Angie Lee, Céline Little, Sarah Marchant, Dali Mwagore, Dale Rutstein andKathleen SullivanEditing:Chloe Browne and Lucio Pezzella, Strategic AgendaDesign and layout:Green Communication DesignACKNOWLEDGEMENTSMany thanks to the following experts for their feedback:George Patton, Frederick Murunga Wekesah, Manasi Kumar, Chiara Servili,Fahmy Hanna, Devora L. Kestel, Lorraine Sherr, Lucie Cluver, Mark Tomlinson,Kathryn Roberts, Katharina Haag, Xanthe Hunt, Daniel Kardefelt-Winther,Gwyther Rees, Ewa Zgrzywa, Alessandra Guedes, Elena Camilletti, ZahrahNesbitt-Ahmed, Josiah Kaplan, Benjamin Perks, Emma Ferguson, Zeinab Hijazi,Patricia Landinez, Neven Knezevic, Caoimhe Nic a Bhaird, Anneloes Koehorst,Sarah Thomsen, Brian Keeley, Ana Nieto, Maaike Arts and Andria Spyridou.Arianna Manzini was supported by Wellcome Trust Secondment Fellowship221455/Z/20/Z

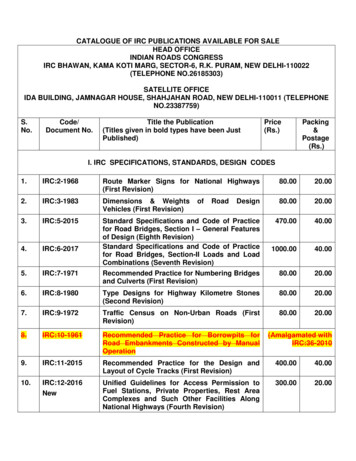

CONTENTSABBREVIATIONSEXECUTIVE SUMMARYBACKGROUND AND CONTEXTMETHODOLOGYOVERVIEW OF STUDIESKEY FINDINGSInternalizing conditions (depression, fear and anxiety,suicidal behaviour, trauma and post-traumatic stress) iv11222263233Externalizing conditions (externalizing behaviouralproblems, alcohol and substance use and abuse) 43Lifestyle behaviours 49Positive mental health outcomes 52THE WAY AHEAD: IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY,PROGRAMMING AND RESEARCHSummary of key research findings 5657Implications for programming and policy 61Implications for research 64Building back better through strengthening child andadolescent mental health systems 65REFERENCESAnnex 1. Supplemental tables for primary studies 6884Annex 2. Overview of studies 103Annex 3. Individual-level factors and mental health outcomes 104Annex 4. UNICEF Office of Research background resources 105Annex 5. Measures of mental health outcomes 106

ivLife in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-19ABBREVIATIONSADHDattention deficit hyperactivity disorderASDautism spectrum disorderCOVIDcoronavirus diseaseDSMDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental DisordersEVDEbola virus diseaseGADgeneralized anxiety disorderH1N1influenza A virus subtype H1N1HIVhuman immunodeficiency virusICDInternational Classification of DiseasesLMICslow- and middle-income countriesMERSMiddle East respiratory syndromeOCDobsessive compulsive disorderODDoppositional defiant disorderPRISMAPreferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviewsand Meta-AnalysesPTSDpost-traumatic stress disorderSAMHSASubstance Abuse and Mental Health Services AdministrationSARSsevere acute respiratory syndromeSARS-CoV-2severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2WHOWorld Health Organization

Life in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-19EXECUTIVESUMMARY1Photo: UNICEF/UNI342592/PanjwaniThe COVID-19 pandemic is focusing global attentionon child and adolescent mental health.The COVID-19 pandemic hasaffected all levels of society globally.Government-imposed lockdowns andschool closures in response to thedisease have significantly disrupted thedaily lives of children and adolescents,leading to them spending increasedtime at home, restricted freedom ofmovement, online learning, and limitedor no physical social interaction withtheir peers. Despite the potential forgreater connection within families,this isolation also risks loss of peersupport and community networks,education and learning, social isolationand uncertainty about COVID-19 andthe future. The pandemic has had asignificant impact, not only on the mentalhealth of children and adolescents,but also on their caregivers, familiesand communities.Before the pandemic, it was estimatedthat diagnosable mental health conditions affected about one in eight(13 per cent) children and adolescentsaged 6–18 years. Further, it was also estimated that around 50 per cent of mentalhealth conditions arise before the age of14, and 75 per cent by the mid-20s.BEFORE THEPANDEMIC:Mental healthconditionsaffected aboutin childrenand adolescentsagedyears.1 86–18

2Life in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-19EXECUTIVE SUMMARYStudies from previous epidemics, suchas Ebola and HIV, and from humanitariansettings with similarities to the COVID-19context – such as quarantine, isolationand stigma – have demonstratedenduring impacts on mental health.These include anxiety, depression andpost-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),although there is limited evidence forhow these conditions have affected childand adolescent mental health duringthese epidemics.Our first report in this series on child andadolescent mental health is entitled MindMatters: Lessons from past crises forchild and adolescent mental health duringCOVID-19. This second report looksat how the early stages of the globalpandemic in 2020 affected the mentalhealth of children and adolescents (thosein the first two decades of life).Our rapid evidence review seeks tounderstand the immediate effectsof COVID-19 on child and adolescent mental health from the initialwave of the pandemic, and applylessons learned to mitigating theseeffects, as well as future healthcrises. To assess the mental health andpsychosocial impact of the COVID-19pandemic on children and adolescents,UNICEF Innocenti conducted a rapidevidence review with a view to understanding two key research questions: What has been the immediate impactof COVID-19 and associated containment measures on the mental healthand psychosocial well-being of childrenand adolescents?findings. we categorized ourinto externalizing,internalizing, and lifestyle-related behavioursand reactions. Which risk and protective factors haveaffected the mental health of childrenand adolescents during the COVID-19pandemic, and how have these factorsvaried across subgroups of childrenand adolescents?The conceptual framework guidingthis rapid review is derived fromthree different instruments: thesocial-ecological systems model; thelife-course perspective; and the socialdeterminants of health approach. Theframework places the child in thefamily, community and society, andexplores the ramifications of COVID-19on the child’s intimate world, theworld around them and the outerworlds of influence. The frameworkalso emphasizes the importance ofpre-existing and ongoing mediatingand moderating risks and protective factors across various ages anddevelopmental stages of the child.Applying a continuum – from positiveto negative – to assess mental healthoutcomes, we categorized our findings into externalizing, internalizing, andlifestyle-related behaviours and reactions. We also looked at positive mentalhealth outcomes of the pandemic. Ourresearch focused on key risk and protective factors including individual and familybackground characteristics, geographicallocation, and interpersonal and societalfactors. It also sought evidence of theimpact on some special populationsand vulnerable groups: children withpre-existing mental health and neurodevelopmental conditions, childrenin humanitarian settings and migrantchildren, and children facing discrimination because of their gender, sexualorientation, or disability.

Life in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-193EXECUTIVE SUMMARYMethodology and overviewOur findings are based on systematicreviews and studies coveringmore than 130,000 children andadolescents across 22 countries.The review conducted systematicdatabase searches of PubMed,PubCovid-19, the Cochrane Collaborationand the Wellcome Trust COVID-MindsNetwork, covering studies publishedbetween 1 November 2019 and30 November 2020. We screenedstudies in two stages according topredefined inclusion and exclusioncriteria. Out of a total of 4,323 studiesidentified, we included a final set of84 peer-reviewed sources for dataextraction and evidence synthesis. Fourresearchers undertook data extractionand evidence synthesis, with eachresearcher cross-checking the extractionand synthesis of another researcher toensure quality control. A formal qualityappraisal of included studies wasnot undertaken.Of the 84 studies, the 77 primarystudies reviewed include data fromover 130,000 children and adolescents from 22 countries. The studiesfocused on children and adolescentsaged 0–19 years, with about 50 percent focusing on adolescents aged10–19 years. The studies reviewedreported on data collected up toAugust 2020 during the early stagesof the pandemic. Consequently, anylonger-lasting mental health impacts –including during subsequent waves ofthe virus and phases of the lockdowns– are not fully captured. Moreover,the timing of government-imposedcontainment measures, includinglockdowns and school closures, variedconsiderably across countries, limitingthe generalizability of specific findings.Most studies were from high- andupper-middle-income countries thatwere sharply affected by high infection and death rates early in thepandemic’s trajectory.The largest share of studies reviewedwas from China (26 per cent), followedby the United States (23 per cent) andItaly (13 per cent): all countries thatwitnessed high infection and death ratesearly in the pandemic. The distributionof studies by region was 36 per centfrom Europe and Central Asia, followedby 30 per cent from East Asia and thePacific, North America (25 per cent),South Asia (4 per cent), the Middle Eastand North Africa (3 per cent), Easternand Southern Africa (2 per cent), andLatin America and the Caribbean(2 per cent). One study was conductedin multiple regions (Eastern andSouthern Africa, West and Central Africa,and the Middle East and North Africa).Only one study was from a low-incomecountry (Ethiopia), and most were fromhigh- or upper-middle-income countries.Distribution of studies by region36%East Asia and the Pacific 30%North America 25%South Asia 4%Middle East and North Africa 3%Eastern and Southern Africa 2%Latin America and the Caribbean 2%Europe and Central AsiaNote: Percentages add up to 102% due to rounding figures.

4Life in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-19EXECUTIVE SUMMARYKEY FINDINGS:attitudes, behaviours andmental health conditionsHigher levels of depression, fear,anxiety, anger, irritability, negativity, conduct disorder, alcoholand substance use and sedentary behaviours compared withpre-pandemic rates were commonlyreported in children and adolescents in 2020, but there were alsopositive perceptions of time spentwith family.angerfear2020depression .family timeMost studies assessed the effects ofCOVID-19 and containment measureson mental health outcomes relating toanxiety, depression, behavioural issuesand positive mental well-being (operationalized as life satisfaction, quality oflife and self-esteem). Findings of specificoutcomes in the early stages of thepandemic are summarized as follows:Depression: Depressivesymptoms (including sadness, loss ofinterest in activities, hopelessness,low energy, irritability and guilt) werecommonly reported in children andadolescents during the COVID-19pandemic. Moderate increase indepressive symptoms and sadnesswere reported, especially among olderadolescents and females.Fear and anxiety: Higher thanpre-pandemic rates of mild and moderateanxiety were reported by children andparents across regions and age groups,especially because of disruptions to dailyroutines and school closures as well as togrowing worry and concern over risk totheir own health and that of their families.Suicidal behaviour: Limitedevidence from preliminary reportsindicates that increases in suiciderates among children and adolescentsin the context of COVID-19 shouldnot be assumed, as there are alsoseveral protective factors that couldarise in the context of this crisis.Trauma and post-traumaticstress: Studies showed increasedstress and adjustment issues amongadolescents, especially because offear of infection and uncertainty dueto quarantine and disruptions to dailyroutines. Studies did not, however,find significantly higher PTSD ratesin children and adolescents since thepandemic onset, and follow-up researchis needed to assess the long-termimpact of the pandemic on PTSD.

Life in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-19EXECUTIVE SUMMARYExternalizing behaviouralproblems: The living conditions broughtupon by the response to the COVID-19pandemic led to an increase in anger,negativity, irritability and inattention,particularly among children with attentiondeficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and/or autism. Parents also reported worsening of conduct problems and disruptivebehaviours among adolescents, as wellas clinginess among younger children.Alcohol and substance use andabuse: Studies indicated an increasein hazardous and problematic alcohol andsubstance use among adolescents sincethe outbreak of the pandemic and foundthis to be associated with behaviouralproblems (including anger and irritability),especially among boys.Lifestyle behaviours: Studiesidentified associations betweenCOVID-19 containment measures (e.g.,home confinement and school closure)and increases in sedentary behaviourand lifestyle changes (e.g., less physical activity, higher exposure to screentime and irregular sleep patterns). Someof these lifestyle changes (especiallyirregular sleep and exercise) were associated with lower quality of life (e.g., lowself-esteem) and increased psychologicaldistress (e.g., anxiety and depression).Use of digital technology during thepandemic provided social connectedness, remote learning opportunities, anda way to cope with isolation and stress.Photo: UNICEF/UNI320964/Positive mental health outcomes:Not all mental health consequencesassociated with the pandemic werenegative. Children and adolescentsreported perceived benefits from homeconfinement (e.g., increased quality timewith family members) and school closure(e.g., respite from schoolwork, examstress and school-related bullying) thatseemed to positively correlate with lifesatisfaction. Engaging in positive copingstrategies (e.g., physical and recreationalactivities), having more time for oneselfor to spend with one’s family and havingmore flexible schedules contributed tochildren’s and adolescents’ well-beingduring the COVID-19 outbreak.5

6Life in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-19EXECUTIVE SUMMARYKEY FINDINGS:risk and protective factorsThis section highlights key risk andprotective factors reported acrossstudies that shaped the way in whichthe COVID-19 pandemic affectedmental health outcomes for children and adolescents, including asmediating and moderating factors.Sex: In most of the studiesreviewed, females reported greaterdepressive symptoms, anxiety and externalizing behavioural symptoms thanmales, while males reported greateralcohol and substance use duringCOVID-19 than their female counterparts.Age: Older children andadolescents reported higher and moresevere rates of depressive symptoms and anxiety than younger onesduring the pandemic. Mixed resultson age differences were reportedfor other mental health outcomes.Location: Children living inmore-affected areas, rural areas,or near the epicentre of COVID-19outbreaks were associated with stresssymptoms, depressive symptoms,anxiety, alcohol and substance use,and increased sleep disturbance.Socio-economic status:Children living in poverty or in families with lower socioe-conomic statuswere found to be at greater risk ofstress and depressive symptoms,whereas higher socio-economicstatus was found to be a protectivefactor for externalizing behaviouralproblems during the pandemic.Moreover, the living conditions andlivelihoods of families were adverselyimpacted by financial hardships duringCOVID-19, exacerbating sadness andworry in caregivers and children.Pre-existing conditions: Childrenand adolescents with pre-existing conditions were more significantly affectedby pandemic-related changes. Childrenand adolescents with neurodevelopmental conditions (e.g., ADHD andautism spectrum disorder) and healthconditions such as HIV, diabetes andcancer had greater fears relating toCOVID-19 risk. Moreover, children livingin low- and middle-income countries(LMICs) or conflict-affected settingswho were exposed to widespreadpoverty, displacement and genderinequalities, experienced depressionduring the pandemic and struggled toadapt to online education. Mental healthservices and other services for children with pre-existing conditions werealso disrupted during COVID-19, withgrave consequences for children withpre-existing mental health conditions.Adverse childhood experiences:Children and adolescents who reportedpre-existing adverse childhood experiences and maltreatment, including abuse,neglect and family dysfunction, wereat increased risk of stress and anxietysymptoms since the pandemic onset.Parenting: Family conflict increasedthe risk of mental distress among children and adolescents, while separationfrom families and parental depression and anxiety were risk factorsfor stress and adjustment issues,

Life in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-19EXECUTIVE SUMMARYdepressive symptoms, and externalizing behavioural problems amongchildren and adolescents. Positiveparenting and caregiver–child communication about the pandemic improvedcoping and well-being among children, adolescents and caregivers.Stigma and discrimination:Stigma based on ethnicity and allforms of racial discrimination (online,in-person and health care related)since the outbreak of the pandemicwere associated with greater anxietyamong these adolescents. In USstudies, discrimination towardsChinese American adolescents wasfound to be particularly acute.Lockdown and isolation: Socialisolation and loneliness during lockdownscontributed to a range of outcomes,including depression, irritability, anxiety,stress, alcohol use and sedentarybehaviours. However, in some studies,children and adolescents reportedperceived benefits from home confinement (such as spending time with family)and school closure (relief from academicstressors), which correlated positivelywith life satisfaction.Coping strategies: Spendingmore time on physical activity and maintaining daily living routines protectedagainst depressive symptoms and wereassociated with better mood states.Stress management, leisure-time activities (e.g., learning an instrument orcooking) and regular communicationwith loved ones were other proactivecoping strategies used to deal withpandemic stressors and lockdowns.Social support andconnectedness: Engaging in recreational activities, including usingtechnology to communicate with lovedones, having more time for oneself orfor one’s family and having more flexibleschedules, protected against anxiety andcontributed to children’s and adolescents’overall well-being during the pandemic.Adherence to stay-at-home ordersand social support and connectednessprotected against depressive symptomsand anxiety.Risk perception: Experienceor fear of exposure to COVID-19 andperceived seriousness of the pandemicwere predictive of stress and depressive symptoms, anxiety and hoardingbehaviour, but they were also associated with health promotion andinfection-prevention behaviours such asgreater physical distancing, disinfectingand news monitoring.Photo: UNICEF/UNI313778/Georgiev7

8Life in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-19EXECUTIVE SUMMARYImplications of findings forpolicy and programmingThe pandemic has impacted all areasof children and young people’s lives.Our review found evidence of increasedstress, anxiety and depressive symptoms, externalizing behavioural problems,and alcohol and substance use sincethe onset of the pandemic. Associationswere also identified between COVID-19containment measures and lifestyledysregulation. However, children andadolescents also reported positive copingstrategies, resilience, social connectedness through digital media, morefamily time and relief from academicstress. The influence of factors suchas demographics, interpersonal relationships and pre-existing conditionsis critical when considering the typeof mental health outcomes reportedsince the COVID-19 outbreak.Several primary recommendationsemerge from the report thathave strong implications forpolicy and programming. Begin early to build mental healthassets of children and adolescents.As positive mental health starts earlyand continues to grow over time withnurture and support, it is imperative to begin building mental healthassets early in life, using provenapproaches in the home, at school andin the community. Foster family-friendly policies.Promoting positive action throughplay, support to parents and qualityfamily time have proved helpful inalleviating stress and fear associated with the pandemic and mobilityrestrictions. The potential benefitsof family-friendly interventions suchas parenting programmes and socialprotection are increasingly clear andapplicable across diverse contexts,including in countries and contextswith underinvested health systems,and they should be strengthenedas the pandemic continues. Invest in age- and gender-sensitivechild and adolescent mental healthcare interventions and services.The COVID-19 crisis has underscoredthe depth of the global mental healthcrisis, including among children andadolescents. Mental health caremust become an increasing prioritywhen designing, implementingand expanding primary health careservices for children and youngpeople – particularly through buildingcapacity of health professionals andother child-related frontline workers.In particular, it will be important forpolicymakers and practitioners todevelop and scale age-appropriate andgender-sensitive interventions, and toadapt evidence-based activities thathave proved beneficial in high-incomecontexts to those children and youngpeople in resource-poor settings. Promote physical activity andgood nutrition for young people.Studies show that those childrenand adolescents who fared well for

Life in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-19EXECUTIVE SUMMARYpositive mental health during the earlystages of the pandemic had accessto physical recreation and improvednutrition. Going forward, governmentsacross the world should invest inindividual, interpersonal and community mental health interventions thatfoster the holistic development andwell-being of children and adolescents,including through promoting theirphysical health and social networks. Make schools a safe space forpositive mental health. As millionsof children and young people return toschool, it is vital that families, frontlineworkers and governments listen tothem and seek to address some of themental distress that both the absenceof school, and schooling itself, maycause them. Ways should be exploredto help them catch up while alsoreducing exam stress to bolster theirmental health, and avenues to makeschools safer and more inclusive for allstudents should be found. Focus on at-risk young populations.Children and adolescents sufferingfrom pre-existing child and adolescent mental health conditions – andthose most affected by exclusionand discrimination based on income,gender, disability, ethnicity and otherdelineators – have been amongthose whose mental health has beenmost affected by the pandemic.Studies show clearly that childrenand adolescents facing the driversof exclusion and discrimination haveseen markedly increased risks. Forpolicy and programming, it will beessential to place greater emphasis onunderstanding even further the mentalhealth stresses that these at-riskpopulations face, and on prioritizinginterventions for them. Address stigma and discrimination in mental health, includingnew and emerging forms. Thepandemic has coincided with a widerglobal discussion on mental healthissues, on inequality, and on racismand discrimination based on ethnicity,and on ways to combat these challenges. Policies and programmesfocused on child and adolescentmental health must address bothgeneralized and continuing stigmarelated to mental health issues, andspecifically stigma against certaingroups as related to the pandemic. Support digital technologies asa force for change. The COVID erahas underlined the essentiality bothof access to digital technologiesfor young people to learn, communicate and grow, and of protectivemechanisms to protect them fromharm and abuse and safeguardtheir mental well-being. Digitaltechnologies can also offer alternative and promising modes ofdelivering mental health psychosocial support services. Therefore, itwill be important to develop innovative, evaluated and ethical strategiesand interventions that can be scaledup to support the mental healthof more children and adolescents,and their parents and caregivers.9

10Life in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-19EXECUTIVE SUMMARYImplications of findingsfor researchOur report has noted four keyevidence gaps to address inthe rapidly growing body ofresearch on COVID-19 and itsmental and psychosocial impacton children and adolescents. 1Build a wider body ofresearch on child and adolescentmental health in LMICsOur findings are largely drawn fromevidence of the countries most affectedby COVID-19 disease early on in 2020 –especially China, Italy and the US. Moreevidence is needed of how it affects childand adolescent mental health in low- andmiddle-income regions and countries –and especially in those regions such asLatin America and Caribbean and SouthAsia where the pandemic has beenparticularly hard-hitting so far, and alsosub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East,where the evidence base of child andadolescent mental health is nascent.2Examine how COVID-19affects mental health in earlyand middle childhoodIn addition, more evidence is required ofearly (0–4 years) and middle childhood(5–9 years), as most of the researchreviewed captured the situation ofadolescents aged 10–19 years. Researchon younger age groups could examinehow COVID-19 affects the developmentoutcomes in early childhood andinvestigate any long-term implicationsof the suspension of primary health careservices during the pandemic.3Widen the evidence base toinclude vulnerable populationsof children and adolescentsOur review did not find evidence ofthe impact of COVID-19 on the mentalhealth of a wide array of vulnerablesocio-economic groups of childrenand young people. These include childmigrants and displaced persons, childlabourers, adolescent parents/caregivers and adolescent pregnant girls,children facing domestic violence, children facing sexual and gender-basedviolence, children living in institutionalcare, children with disabilities, and youthwith non-binary genders and LGBTQI youth. Future research should andmust examine the impacts (especiallythe enduring impact) of the COVID-19pandemic on the mental health of thesevulnerable populations.4Investigate the longer-termimpact of the pandemic on childand adolescent mental healthOur findings are limited to studiespublished between 1 November 2019and 30 November 2020. It should benoted that mental health conditions mayc

iv Life in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-19 ABBREVIATIONS ADHD attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ASD autism spectrum disorder COVID coronavirus disease DSM Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders EVD Ebola virus disease GAD generalized anxiety disorder H1N1 influenza A virus subtype H1N1