Transcription

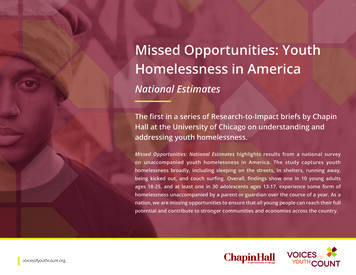

Missed Opportunities: YouthHomelessness in AmericaNational EstimatesThe first in a series of Research-to-Impact briefs by ChapinHall at the University of Chicago on understanding andaddressing youth homelessness.Missed Opportunities: National Estimates highlights results from a national surveyon unaccompanied youth homelessness in America. The study captures youthhomelessness broadly, including sleeping on the streets, in shelters, running away,being kicked out, and couch surfing. Overall, findings show one in 10 young adultsages 18-25, and at least one in 30 adolescents ages 13-17, experience some form ofhomelessness unaccompanied by a parent or guardian over the course of a year. As anation, we are missing opportunities to ensure that all young people can reach their fullpotential and contribute to stronger communities and economies across the country.Voices of Youth Count // Logo Guidelinesour logowithout taglinevoicesofyouthcount.orgVoices

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYVoices of Youth: Natalie's StoryVoices of Youth CountAt age 14 in a small town in Washington State, Natalie’s experienceThrough multiple methods and research angles, Voices of Youth Countsought to capture and understand the voices and experiences ofthousands of young people like Natalie. While the deprivation of housingstability was the common thread in Voices of Youth Count research, thestories of youth homelessness—and the opportunities for intervention—rarely centered on housing alone. Every experience, every youth, wasunique. Yet, with the data gained through Voices of Youth Count, we canbegin to better understand the scale and scope of the challenge and thepatterns that can guide smarter policy and practice.with homelessness began. Natalie’s dad left her family, and her momfell into depression and started using methamphetamines. “[I]f shewasn’t drunk or high, she was gone,” Natalie noted in one part ofVoices of Youth Count’s research efforts. For the next six months,Natalie cared for her four younger siblings. She started to miss schooland ultimately dropped out. The stress of her circumstance mounted.Through friends, she encountered meth, a drug that had becometragically common in her community. She started using. This onlyadded to conflict with her mom, and, after a fight with her mom’snew boyfriend, Natalie was kicked out.Natalie then cycled between couch surfing and trap houses, where illegaldrugs are sold. She exchanged sex with an older man so that she could“have a roof over [her] head.” Natalie traveled to other cities for housingand informal support. By 17, when chemical dependency had taken astrong hold, she stayed for extended periods in the shed of someone sheknew. Natalie found herself regularly returning to juvenile detention—where she says she was grateful for a bed to sleep in and respites of safety.When Natalie was interviewed, she was about to embark on a residentialtreatment program. Asked about her future, she said, "I want to be homewith my mom, and I want to stop using, and I want to be clean with mymom. I want to be able to see my siblings.”Adolescence and young adulthood represent a key developmental window.Every day of housing instability and the associated stress in the lives ofyoung people like Natalie represents missed opportunities to supporthealthy development and transitions to productive adulthood. Voices ofYouth Count gives voice to young people like Natalie across our nation whodo not have the necessary supports to achieve independence and maketheir unique contributions to our society.2Since 1974, when Congress first passed what is now known as the Runawayand Homeless Youth Act (RHYA), the nation has recognized its sharedresponsibility to care for young people who live on the streets or apart from asafe and stable home. This landmark legislation, subsequent changes withinstatutes across multiple federal agencies, and ongoing national initiativessupport a basic set of services for youth who experience homelessnessand are at risk of homelessness. In 2012, the U.S. Interagency Council onHomelessness (USICH) amended the national plan to end homelessnessto include a specific Federal Framework to End Youth Homelessness,outlining steps that need to be coordinated across Federal agencies toadvance the goal of ending youth homelessness by 2020. However, despiteimportant national actions—and many efforts at the state and communitylevels—a sizable percentage of American youth continues to experiencehomelessness. The problem is solvable, but much remains to be done.Missed Opportunities: National Estimates summarizes the results of theVoices of Youth Count national survey that estimates the percentageof United States youth, ages 13 to 25, who have experiencedunaccompanied homelessness at least once during a recent 12-monthperiod. Results show that approximately one in 10 American young adultsages 18 to 25, and at least one in 30 adolescent minors ages 13 to 17,endures some form of homelessness.

Key to understanding these estimates is the factthat young people—like Natalie—often shift amongtemporary circumstances such as living on thestreets and couch surfing in unstable locations.The Voices of Youth Count national survey alsoreveals that urban and rural youth experiencehomelessness at similar rates and thatparticular subpopulations are at higher risk forhomelessness, including black and Hispanicyouth; lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgenderyouth (LGBT); youth who do not complete highschool; and youth who are parents.Previous research shows that the longer youthexperience homelessness, the harder it is toescape homelessness and contribute to strongerfamilies, communities, and economies. To exithomelessness permanently, youth requirehousing and support services tailored to theirunique developmental needs. Although manyfactors drive youth from their homes, includingeconomic hardship, conflict, abuse, and neglect,the young people thrust into this situation sharedifficulty and uncertainty.Moving Toward SolutionsUntil now, one major challenge to puttingsolutions in place has been the lack of credibledata on the size and characteristics of the youthpopulation who experience homelessness anda way to track how this population changesover time. Without credible numbers anddeeper understanding, it has been difficult forthe nation to develop a well-resourced andtailored response to address this problem inour communities. It has also been impossible toreliably track the nation’s progress toward its goalof ending youth homelessness.Missed Opportunities: National Estimates providesCongress with new foundational evidence forunderstanding the scale, scope, and urgency ofyouth homelessness in America.Voices of Youth Count will bring forward moreevidence in the months to come. Look forResearch-to-Impact briefs related to trajectoriesinto homelessness, the dynamics betweeninteractions with systems like child welfareand youth homelessness, synthesis of theevidence regarding interventions to addressyouth homelessness, and deep explorations ofthe experiences faced by specific subgroups ofyoung people.Beyond the findings, Voices of Youth Countwill offer implications and recommendationsintended to focus the attention of Congresson existing policy opportunities—like the RHYAand others—that might be leveraged to makechange. Recommendations are intended tobe the beginning of a dialogue about tangiblechanges to the nation’s laws, regulations, andprograms, not an end point. In each brief, Voicesof Youth Count will speak to the evidence whileseeking solutions.Adolescence and youngadulthood represent a keydevelopmental window.Every day of housinginstability represents missedopportunities to supporthealthy development andtransitions to productiveadulthood.No more missedopportunities.No more missed opportunities.3

RECOMMENDATIONSConduct national estimates of youthhomelessness biennially to track our progressin ending youth homelessness. See Finding 1.Fund housing interventions, services, outreach,and prevention efforts in accordance with thescale of youth homelessness, accounting fordifferent needs. See Finding 1.Encourage assessment and service deliverydecisions that are responsive to the diversityand fluidity of circumstances among youthexperiencing homelessness. See Finding 2.Build prevention efforts in systems whereyouth likely to experience homelessness are inour care: child welfare, juvenile justice, andeducation. See Finding 3.4Acknowledge unique developmental andhousing needs for a young population, andadapt services to meet those needs.See Finding 3.Tailor supports for rural youth experiencinghomelessness to account for more limitedservice infrastructure over a larger terrain.See Finding 4.Develop strategies to address thedisproportionate risk for homelessness amongspecific subpopulations, including pregnantand parenting, LGBT, African American andHispanic youth, and young people without highschool diplomas. See Finding 5.

A NATIONAL SURVEY APPROACHQuantifying the number of youth struggling with homelessness presents a challengeFigure 1. Prevalence of YouthHomelessness in Americadue to the transitory and hidden nature of youth experiences. For example, after Nataliewas kicked out of her home at 14, she found shelter in varied locations such as on otherpeople’s couches, in a trap house, or in a shed. Because she didn’t stay on the streetor in a shelter, she might not have been included in a community effort to capture theextent of youth homelessness.To gain a fuller picture, Voices of Youth Count primarily draws on a nationallyinrepresentative phone survey for national estimates in this brief, but we also includesome insights from other research components—like in-depth interviews and brief youthyoung adults ages 18-25 experienced a formsurveys that took place during local Youth Counts across the country.of homelessness over a 12-month period.The national survey interviewed 26,161 people, who were broadly representative of theThat’s 3.5 million young adults. About half of thempopulation of the nation, during 2016 and 2017. The study interviewed adults whoseinvolved explicitly reported homelessness while thehouseholds had youth and young adults ages 13-25 over the year and respondentsother half involved couch surfing only.who were ages 18-25. The respondents then answered questions about occurrences ofdifferent types of youth homelessness experienced by the respondents themselves (ifages 18-25) or by young people (ages 13-25) who were in the household. Page 15 includeskey terms for this study.The survey sought to identify how common, or prevalent, youth homelessness is in America.The study also aimed to collect information on the characteristics of youth experiencinginhomelessness and identify subpopulations at higher risk of homelessness. Voices of YouthCount chose this approach to national estimation of youth homelessness not only becauseyouth ages 13-17 experienced a form ofof its technical strengths, but also because of its cost efficiency and replicability.homelessness over a 12-month period.The Voices of Youth Count national survey was reinforced through follow-up interviews.That’s about 700,000 youth. About three-quartersA random sample of 150 people who reported on any youth homelessness were calledof them involved explicitly reported homelessnessin an effort to learn more. Details on the methodology of the national survey, along with(including running away or being kicked out) andits strengths and limitations, are reported in the Journal of Adolescent Health article titledone-quarter involved couch surfing only.“Prevalence and Correlates of Youth Homelessness in the United States.” This brief alsodraws on more than 4,000 in-person brief youth surveys in 22 counties and 215 in-depthinterviews with youth in five counties who had experiences of homelessness.5

Five MajorFindingsFinding 1.Youth homelessness is abroad and hidden challengeThe survey results revealed that the nationhas a serious and substantial challenge withyouth homelessness. As shown in Figure 1,over a 12-month period, 3.0% of householdswith 13- to 17-year-olds reported explicit youthhomelessness (including running away or beingFinding 1. Youth homelessness isa broad and hidden challengekicked out) and 1.3% reported experiencesthat solely involved couch surfing, resulting inan overall 4.3% household prevalence of anyhomelessness. We estimate that this translates toFinding 2. Youth homelessnessinvolves diverse experiences andcircumstancesFinding 3. Prevention and earlyintervention are essentialFinding 4. Youth homelessnessaffects rural youth at similar levelsFinding 5. Some youth are atgreater risk of experiencinghomelessnessa minimum of 700,000 adolescent minors, or 1 in30 of the total population of 13- to 17-year-olds.with others while lacking a home of their own.These experiences are the most invisible. Previousresearch shows that couch surfing generallytakes place early in people’s struggles withhomelessness, with sleeping more on the streetshappening at later stages of homelessness. Ourestimates also capture large numbers of youngpeople that are hidden to other counts anddata. For example, our estimates for adolescentminors are larger than those produced by datacollected by school officials because our surveyincluded out-of-school youth, and it does notdepend on the strengths or limitations of schoolidentification systems of student homelessness.The prevalence climbs even higher when lookingOur estimates are bigger than those from point-at homelessness among young adults (agesin-time counts largely because we capture18-25). Twelve-month population prevalenceexperiences over a year, rather than on one night.rates for young adults were 5.2% for explicitOur survey approach also includes more hiddenhomelessness, 4.5% for couch surfing only,homelessness of youth who are not in the streetsand 9.7% overall. The estimated count revealsor shelters at the time of a point-in-time count.more than 3.5 million, or 1 in 10, young adultsexperienced homelessness in a year. It could beImplications & Recommendationsthat the size of the difference in rates betweenThese national estimates reveal that keythe younger and older youth was due partlysystems and federal programs need to beto underestimation of the minors becausesignificantly better resourced to address thethey were not contacted directly. However,scale of youth homelessness. For example,this upward trend is consistent with broaderaccording to 2014 data collected by the U.S.public health research that shows increasedDepartment of Health and Human Serviceslevels of vulnerability during the transition from(HHS), 50,000 youth were served by the twoadolescence to young adulthood.major runaway and homeless youth programsIn addition to showing a broad national challenge,these estimates reveal a largely hidden problemof youth homelessness. A large share of youth6included were couch surfing or otherwise stayinginvolving short- or longer-term housing in2014. Per the U.S. Department of Housingand Urban Development’s (HUD) 2016 Annual

Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, there were 21,000situations to get by when they cannot stay in a home ofbeds or housing spaces under different HUD-funded programstheir own.targeted to unaccompanied and parenting youth in 2016. Evenif we conservatively assume that only a small share of youthexperiencing any homelessness in a year needs short- or longterm housing interventions, these numbers fall well short.One 19-year-old interviewed, for instance, shared the followingexperience of staying at a friend’s before returning to sleeping in acar: “[My friend] had a small bed, so I just crashed on the floor. She hada boyfriend and he would stay over a lot of the time, so it was just, INow, with the first national estimate of youth homelessnessfelt as an inconvenience to them. So I—although they didn’t force me outcomplete, Congress has a solid foundation for conductingof their house—I kind of fibbed and said that I was planning on gettingfuture estimates. The national survey has significantly advancedan apartment so that they weren’t worried about me, and I moved backunderstanding of the scale and characteristics of this previouslyinto my car for a bit.”hidden challenge. It also achieved these insights through anunderlying approach that is replicable and cost-efficient. At thesame time, it was a first effort that can be fine-tuned throughmore detailed measures and additional approaches to collectinformation directly from adolescent minors in the future.Voices of Youth Count encourages Congress to act quickly to refineRHYA language, and appropriate necessary funds, to allow forsubsequent national prevalence and incidence estimates everytwo years, in alignment with the frequency of HUD biennial pointin-time counts, to ensure Congress has up-to-date evidence fortracking and decision making. The language and appropriationsshould reinforce the importance of collecting information on bothadolescent minors—an especially key stage for prevention—andyoung adults. In this way, the nation can track progress towardpreventing and ending youth homelessness.Finding 2. Youth homelessness involves diverseexperiences and circumstancesWhile the concept of “homelessness” might seemstraightforward, in reality it takes many forms in terms ofsituations, acuity, safety, needs, and duration of events. Thesurvey confirms a scenario of American youth homelessnessin which a shifting population of young people uses temporaryAccording to analysis of the national survey follow-up interviews,the vast majority—72%—who experienced “literal homelessness”(generally, sleeping on the streets, in a car, or in a shelter) also saidthey had stayed with others while unstably housed.In looking at safety, about half of the follow-up interviewrespondents believed that the youth was unsafe during theirexperiences of explicit homelessness or couch surfing. Theseyouth need access to rapid family reconnection supports whenappropriate, safe brief respites (such as trauma-informedyouth shelters or host homes), or long-term safe and stablehousing options, depending on their needs and preferences. Yetmany youth self-organize temporary housing through informalnetworks—such as couch surfing with a friend or relative—that issafe, if unstable. In these cases, youth may need supports to geton a path to housing stability while not necessarily needing formalshort-term shelter or respite housing.Among other youth surveyed, supports beyond housing arewarranted to ensure sustainable exits from homelessness. Forinstance, 29% of youth were reported as having substance useproblems, and 69% were indicated as having mental healthdifficulties, while experiencing homelessness. Just as Natalie’sstory highlighted, having safe and stable housing is the critical7

starting point for youth to benefit from otherFigure 2. Range of Homeless Experiencesservices. Often, arranging safe and stablehousing involves working with the family. InWhile the concept of “homelessness” might seem straightforward, in reality it takes many forms in terms ofsituations, acuity, safety, needs, and duration of events. The survey confirms a scenario of American youthhomelessness in which a shifting population of young people uses temporary situations to get by when theycannot stay in a home of their own.other cases, it involves ensuring that youngData depict the experiences of youth (13-25), over a 12-month period, as described during the survey followup interviews with a smaller sample of respondents.tailored to individual youth needs is essential72%barrier housing options. In addition to stablehousing, integrating meaningful servicesto help them exit homelessness for good.For still others, situations are temporary42%of those who slepton the streets orin shelters alsocouch surfed.people have access to other long-term, low-and nonrecurring during the year, and theseexperienced twoor more episodes.experiences and circumstances likewiserequire different responses. For example,according to analysis of the follow-upinterviews, at least one in four young people52%feltunsafewho experienced some form of homelessnesshad experiences of housing instabilitylasting less than one month. During a oneyear period, over half of the youth with any73%experiences of homelessness only had oneexperienced an episode lastingmore than a month.episode. Older research has shown thatmost runaway/kicked out experiences amongminors tend to last for less than a week.All of these experiences can expose youthto risks and can be warning signs of futurehomelessness. But many may not need longterm housing interventions so much as accessto supports to stay safely housed duringhomelessness spells and services to ensurethat they never have to relive homelessnessin the future.8

Implications & RecommendationsGiven the differences among youthhomelessness situations in acuity, needs,and duration, we recommend Congressencourage well-rounded assessments ofyoung people’s overall circumstances toinform access to housing and supportservices and to develop better serviceFinding 3. Prevention and earlyintervention are essentialThe national survey revealed that a largenumber of youth come into homelessnessfor the first time throughout the course ofa single year. In fact, about half of the youngpeople in the study, ages 13 to 25, who werehomeless during the 12-month period studieddelivery models.experienced homelessness for the first time in theirTo deliver well-tailored support and services,reactive policies and programs alone.these assessments should take into accountyoung people’s sleeping arrangements overtime, the conditions of these arrangements,age-appropriate risk and protective factors,relationships and family history (whenappropriate), and individual preferences.Federal policy should also encourageauthentic youth collaboration in any fundingor program addressing youth homelessness,to ensure that young people’s lived experiencecontributes to smarter strategies to addresstheir needs and aspirations.Figure 3. Incidence ofFirst Time Homelessnesslives. This dynamic cannot be fully addressed withAbout half of the youth who experiencedhomelessness over a year faced homelessness.for the first time.Prevention and early intervention solutionsare needed to stop the flow of youth intohomelessness experiences; this point wasreinforced by the Voices of Youth Count’sin-depth interviews in five communities.The majority of young adults (ages 18-25)interviewed had experiences of homelessnessor housing instability that started in childhoodor adolescence. For many young peopleinterviewed (ages 13-25)—nearly a quarter—unaccompanied experiences had precursorsin the context of family homelessness. Overone-third of youth experienced the death of aparent or caregiver, underscoring early traumaand disruptions that can contribute to paths ofinstability and, ultimately, homelessness. Theseinsights from in-depth interviews reinforce theextent to which early actions to address risksand boost youth resilience can help curb thetrajectories of young people into homelessness.9

Further, key systems present undertapped opportunities foralready play a role in ensuring health and well-being, especiallyactions to prevent youth homelessness. Across 22 counties,for adolescent minors. Voices of Youth Count brief youth surveysmore than 4,000 in-person brief youth surveys showed thatfurther documented that young people who have been in childnearly one-third of youth experiencing homelessness hadwelfare or justice systems, or lack a high school diploma, are atexperiences with foster care and nearly half had been inespecially high risk of homelessness. Public systems can and dojuvenile detention, jail, or prison. While these statistics dohave an impact.not reveal the nature of relationships between systems andhomelessness, they do suggest that these systems offerimportant entry points for preventing large numbers of youthfrom becoming homeless.Implications and RecommendationsThe findings suggest that local, state, and nationalprevention strategies and resources are essential. Noone system alone can address the multiple needs of thesevulnerable young people. Policies that cut across federalprograms are necessary to build a strong prevention safetyand implement plans that identify youth at risk of homelessnessor housing instability and initiate service referrals. The mostobvious mechanisms for Congress to leverage include the JuvenileJustice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) and Title IV-B ofthe Social Security Act (for child welfare), expanding resources foroutreach and drop-in centers in RHYA, and adequately supportingidentification and assistance measures for youth homelessnesspresent in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA, for education).any experiences that do take place are brief and nonrecurrent.Finding 4. Youth homelessness affects rural youthat similar levelsWith close engagement of multiple federal agencies, theBefore Voices of Youth Count, little was known about theUSICH could facilitate development of a specific cross-sectoraldegree of youth homelessness in rural areas compared tostrategy on prevention of youth homelessness, and Congressurban areas. The results indicate that, despite more visible signsshould consider appropriating necessary resources for itsof homelessness such as youth asking for help on city corners,implementation.youth in rural, suburban, and urban counties experience verynet to avoid homelessness before it begins, and to ensure thatCongress has an essential role to play in shaping federalprograms for youth at high risk of homelessness. They can act toemphasize the importance of prevention and early interventionin legislation. They can also encourage that programs that serveyouth experiencing homelessness use an age-appropriatedevelopmental lens in creating services and support systems.Furthermore, Congress should consider expanding strongerhomelessness prevention and early intervention capacities toother public systems like child welfare, schools, and justice that10In particular, Congress should encourage these systems to developsimilar prevalence rates of homelessness. In predominantly ruralcounties, 9.2% of young adults reported any homelessness while,in predominantly urban counties, the prevalence rate was 9.6%.Household prevalence of any homelessness among adolescentsages 13-17 was 4.4% in predominantly rural counties and 4.2% inmainly urban counties.Said differently, this means that as a share of the populationsize, youth homelessness is just as much of a challenge in ruralcommunities as it is in more urban communities. Of course,the number of youth experiencing homelessness in urban and

suburban areas is much larger than the numberin rural areas because a larger share of the USpopulation lives in urban and suburban areas.As a country, we need tailored strategies toreach all of these young people.One interesting distinction is that youth inrural communities seem to rely more on couchsurfing, probably due to a lack of shelter andhousing services in their communities. Thenational survey suggests modestly higherrates of couch surfing in the least denselypopulated counties when compared to thosewith the highest density. But the nationalsurvey did not show where there might havebeen heavier reliance on some sleepingarrangements over others because its aim wasto assess whether a youth couch surfed atall. The 4,000 in-person Youth Count surveysacross 22 counties, on the other hand, showsleeping arrangements on a given night. Thiscomponent of the research found that youthexperiencing homelessness in rural countieswere twice as likely as youth in medium andlarge population counties to be staying withothers, rather than in shelters or on thestreets, on the night of the count. These cross-Implications and RecommendationsThe findings highlight that youth in ruraljurisdictions require a strong set of tailoredsupports. Rural areas face unique challengesFigure 4. Youth HomelessnessAffects Rural and Urban AreasAlikegiven that youth homelessness is spread acrossa larger space with greater hiddenness andRates of youth experiencing homelessness weremore limited services infrastructure. Federalsimilar in rural and nonrural areas.programs addressing youth homelessnessshould encourage and support coordinationand peer learning across communities withrural geographies to enhance the supportsprovided to youth.Young Adults 18-259.6%Population prevalencein rural counties.9.2%Population prevalence inurban counties.Through legislation like RHYA and theHEARTH Act, policymakers could also considerappropriating resources to allow for tailoredoutreach strategies and provision of servicesin rural communities, building on lessons frompilots funded by HHS and HUD. Congressshould also consider supporting the evaluationof services delivered in rural communities toensure interventions are meeting the needs ofthis group of young people.Youth 13-174.4%Household prevalencein rural counties.4.2%Household prevalencein urban counties.component findings underscore how hiddenmany young people are who experiencehomelessness in rural settings and the needfor more creative identification and outreachapproaches to support them.11

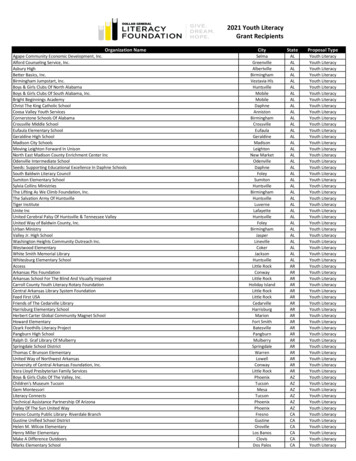

Figure 5. Youth at Greater Risk of Experiencing HomelessnessFinding 5. Some youth are at greaterrisk of experiencing homelessnessStatistics describe the relative risk of certain groups of young adults, 18-25, having reportedUnderstanding that certain groups of“explicit homelessness” in the last 12 months.young people are more likely to experiencehomelessness can prompt targetedstrategies to speed progress toward endingyouth homelessness (see Figure 5). Voices346%Youth with less than a highschool diploma or GEDhad a 346% higher risk than theirpeers who completed high school.162%Youth reporting annual householdincome of less than 24,000had

Missed Opportunities: National Estimates summarizes the results of the Voices of Youth Count national survey that estimates the percentage of United States youth, ages 13 to 25, who have experienced unaccompanied homelessness at least once during a recent 12-month period. Results show that approximately one in 10 American young adults