Transcription

R O A D S A F E T Y I N C I T I Z E N S H I P: A K E Y S TA G E 4 R E S O U R C ETTeachers’ notesLearning to drive or rideDrink, drugs and drivingThe impact of the mediaPassenger safety

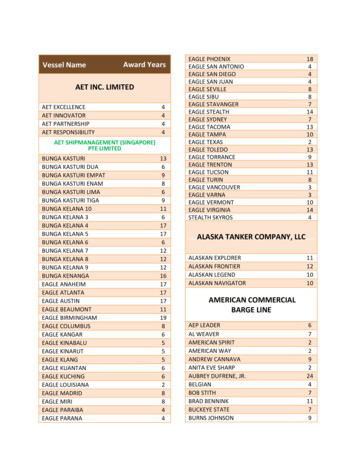

ContentsIntroduction2Learning to Drive or Ride5Drink, Drugs and Driving7The Impact of the Media10Passenger Safety12Areas of the CitizenshipCurriculum Covered15ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThis resource has been produced by a Working Group comprising:Karen CharlesJuliet BarrattNigel HorsleyHelen HillLiz KnightRoyal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA)Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA)Leicestershire County CouncilWolverhampton City CouncilLondon Borough of HounslowWith help from:Gill WaringDawn GuzzettaAmanda LeemingDouglas SmithDennis EdwardsWrexham County Borough CouncilThe John Cleveland College, Hinckley, LeicestershireThe John Cleveland College, Hinckley, LeicestershireSwanshurst School, BirminghamHamstead Hall School, BirminghamObserverJohn LloydDfES Citizenship TeamThe Working Group would like to express its gratitude to everyone who contributedto the development of the resource and especially to the Department for Transportwho funded the project.

IntroductionRoad safety is an important issue for students atKey Stage 4 (KS4) and upwards. Young peopleaged 15/16 years are moving away from parentalcontrol, making choices about life after GCSEsand are more ‘in control’ of their lives. Socialisingis important and there is increasing peer grouppressure. Risk taking and thrill seeking play abigger part in their lives and in some cases, sodoes exposure to criminality.Therefore, this resource has been developed toallow students to ‘dip into’ it when time permits.This could be during class time at the start of theday, or during lesson time. It is not necessary tocomplete all of the activities or discussions,students can pick and choose what to do,depending on the time they have. In this way, theresource is intended to be different to formallesson plans.At 15 years students are beginning to think aboutother forms of transport, like mopeds andscooters. They may have started to think aboutdriving and may have friends who are able todrive. They are vulnerable on the roads and willtake risks.Lesson plans for Citizenship with a road safetytheme are available from theDepartment for Transport and can be accessed atwww.databases.dft.gov.uk/secondary When children travel by car the risk of death orserious injury is highest when they are aged 14or 15 years.A girl of 15 is almost 3 times more likely to bekilled or seriously injured in a car than a girlof 13.Over 50% of the 15 year olds killed or seriouslyinjured in cars are being driven by driversunder the age of 21. 1It is likely that students will have received someroad safety education at primary school, but thisis often learning about rules and may not haveinvolved students assessing risk and consideringthe consequences of their actions. By includingroad safety in the curriculum for KS4 and above,there is an opportunity for students to developthe skills necessary to make sensible, safe choicesand enhance their personal development andsafety.However, road safety is not specifically includedin the curriculum and although, as a topic, itreadily fits with Citizenship, it often becomessqueezed out by more ‘popular’ topics, like drugsand sexual health. As a non-examinable subject,the time afforded for Citizenship studies at KS4and above can be extremely constrained withinthe timetable.1A range of teaching resource materials are alsoproduced as part of the ‘Think’ campaign and canbe accessed at www.thinkroadsafety.gov.ukThe ResourceAlthough the resource is primarily aimed atyoung people at Key Stage 4 and links directlywith the KS4 Citizenship agenda, it can also beused by older students. The resource comprisesthese teachers notes and four student sheets,covering the following topics: Learning to Drive or RideDrink, Drugs and DrivingThe Impact of the MediaPassenger SafetyHow to use the resourceIt is suggested that the teacherkeeps the CD ROM, and copies thefour student sheets, but not theTeachers’ Notes, onto the schoolnetwork for the pupils to access.‘The Facts about Road Accidents and Children’: The AA Motoring Trust2

Each student sheet contains key facts, ideas fordiscussion, student activities and links to relevantwebsites and other sources of information. Thestudents are encouraged to research and discoverthe information that they need to complete theactivities and discussions, using the internet. Notall of the information required to complete thework is on the sheet.The resource is not intended to be prescriptivebut gives the opportunity for student-led activityand research. It is anticipated that the studentswill mostly work through the student sheets ingroups, pairs or individually. Teachers will need toassess the ability of the student group anddecide on the amount of assistance that will berequired to complete the work and also decidehow much of the work the group can achieve inthe time allowed.Students will be requested to: Research issues and problems by analysinginformation from this resource and othersources, including the analysis of statistics. Express, justify and defend orally and inwriting their own personal opinions aboutvarious road safety issues, problems or events. Contribute to group discussions anddebate issues.Activities will require students to: Use their imagination Consider other people’s opinions Formulate and express their own opinions Reflect on the process of participatingThe activities and discussions allow students torecognise their vulnerability as road users andrecognise that safety is about choices. The workwill help students think about their ownbehaviour.Assessment in CitizenshipAssessment should be a planned part of effectiveteaching and learning. The Qualifications andCurriculum Authority publishes guidance onassessment, recording and reporting Citizenshipat key stages 1-4 (www.qca.org.uk/). This isdesigned to help schools work with pupils to3develop appropriate and manageable ways ofassessing progress and achievement incitizenship.The guidance includes:The requirements for assessment, recordingand reporting The principles of assessment in citizenship Progression in citizenship Managing and coordinating assessment,recording and reporting in citizenship Questions to help teachers and pupils planassessment Examples of how different schools mayorganise assessment, recording and reportingcitizenship Examples of citizenship to parents Further sources of information It is a good idea to obtain this resource and referto it when writing your scheme of work forcitizenship.Other useful sources of information include‘The National Curriculum Handbook forsecondary teachers’ QCA/99/458;(www.nc.uk.net) and the DfES Citizenshipwebsite: sion and debate is used throughoutthe worksheets. Enabling students to poseand define problems and justify theiropinions is an integral part of theCitizenship curriculum. It is left for theteacher to decide how these discussionsand debates will be conducted and whatthe outcomes will be. Some of the studentacitivities in the resource conclude with aclass debate on the issue. There isguidance below on formal debates, ifrequired.

Guidance on Formal DebatesStudents should be encouraged to: Listen to each other Make sure that everyone has a chanceto speak Support each other and not put peers down Be helpful and supportive whenchallenging views Remember that everyone has a right topass if they do not want to speak onan issue Show appreciation when someoneexplains something wellAlternatively a debate can have a formalstructure with students taking on specific roles: A Chair – to preside over the debate andensure everyone has a fair chance to speakand also time keep to ensure each speakerhas the same amount of time to presenthis/her case. Speakers – usually there are two speakersrepresenting each side of the debate butthere can be a speaker and one or moresupporting speakers for each side. A record keeper – to make notes on what isbeing discussed and the arguments beingput forward Audience – to put questions to the speakers2In a formal structure the Chair proposes themotion in the following terms ‘This classbelieves that there should be an increaseddriving age to 21 years’. The Chair takes a voteon the issue. The Chair then introduces eachspeaker usually with the first speakersupporting the motion then the first speakeragainst and so on. Each speaker is allowed aset period of time, eg: five minutes.At the conclusion of the speeches the Chairinvites contributions from the audience. It isusually a good idea to plan several questionsin advance in order to get the discussiongoing. The Chair controls the debate, decidingwho is allowed to ask questions and ensuresthat the discussion does not exceed a certainperiod of time, eg: 10 minutes.If desired, each side can select one speaker togive a three minute summing upThe Chair then takes a second vote to see ifopinion has altered as a result of thearguments put forward. 2DfES: Citizenship: A teacher’s Resource Pack to Support Active Citizenship in the Classroom and the Community. www.dfes.co.uk/citizenshipLearning Objectives and Desired OutcomesIt is important to collaborate with students toestablish and identify the learning objectives forthe tasks used from this resource. This must bedone at the outset. Learning objectives cannotbe prescribed as these will depend on theindividual use of the resource and the activitiesthat teacher and students decide to engage in.The same will apply to desired outcomes,although some guidance is offered in relation toeach student sheet. Again these need to beidentified at the start of the work.The Student WorksheetsThe following sections contain backgroundinformation for each topic and key issue in thestudent sheets. There is guidance on learningoutcomes and advice on where students canfind information, using the internet, for theactivities.4

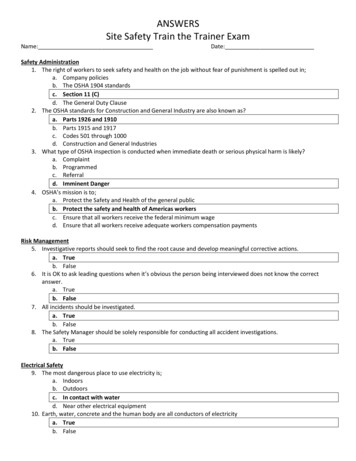

Learning to Drive or Ride Student SheetBackground InformationLearning to drive is a relatively safe activity; veryfew learner drivers crash during superviseddriving lessons. However, the risk increasesdramatically as soon as a new driver passes theirtest and can drive unsupervised. Young andnovice drivers are a high risk group because theyhave not had time to gain driving experience,they tend to be over-confident and poor atassessing hazards and risks.In particular the following factors combine toexplain why novice drivers have more crashes:Age and Experience: The majority of novicedrivers are young and are more likely to beinvolved in crashes. Once they have had just oneor two years of driving experience, their crash riskreduces. Overall the accident risk of 17 year olddrivers reduces by 43% after their first year ofdriving experience.Attitude and Gender: Young, male drivers areparticularly likely to choose to drive indeliberately risky ways and are more likely tocrash than young female drivers. They are morelikely to commit driving offences. Young driversare more willing to break speed limits, drive tooclose and cut corners than more experienceddrivers.Driving Skills: Young drivers tend to have goodvehicle control skills but are poor at identifyingpotential hazards and assessing their risk. Youngdrivers also overestimate their ability to avoid thehazard and crash.Passengers: Young drivers who carry young (peer)passengers are more likely to crash. This is worsewith male drivers and male passengers, possiblybecause they tend to show off.Learning OutcomesBy completing the activities and discussionsstudents should have a better understanding ofwhy new drivers are at risk, how driver trainingand practice helps to reduce this risk and whatthey can do after passing their Test to reduce therisk still further. Students should have an5awareness of the costs involved in buying andrunning a motor vehicle and a betterappreciation that the cheapest option is notnecessarily the safest.Activity iExplore the financial implications ofbeing a car or motorcycle owner.The information needed here canbe pieced together from a numberof sources: DVLA website(www.dvla.gov.uk), enquiries to localdriving schools, enquiries to insurancecompanies – quotes can be obtained viathe internet, advertisements in the localpress, asking friends, family and teachers.Activityi Find out the number, type and causesof crashes that young drivers haveand why RoSPA’s report ‘Young and NoviceDrivers’ is a good starting point and canbe downloaded from www.rospa.com(Click on ‘Road Safety’ then ‘Advice andInformation’ then ‘Young drivers’). Discover the most recent statistics fortwo wheeled motor vehicle casualtiesand decide which category of rider ismost at risk.The Transport Statistics section ofwww.dft.gov.uk contains an annualpublication,‘Road Casualties GreatBritain: The Casualty Report’. There arealso quarterly bulletins published onthe site with more recent figures.

DiscussionPoints 41Find out about licence renewal andrevocation and the rules that applyspecifically to new drivers.www.dvla.gov.uk gives information aboutlicence requirements, renewal and revocation.The Road Traffic (New Drivers) Act 1995 hasimplications for drivers within the first twoyears of passing their test and is outlined inRoSPA’s report,‘Young and Novice Drivers’. Consider the arguments for and againstrequiring drivers to renew their licences ona much more regular basis than currentlyrequired.The arguments for regular refreshertraining include: Regular assessment of driving skillsand ability. Refresh and update skills, particularly inlight of advancing vehicle technology. Update knowledge – keeping abreast ofchanges in road traffic law. Highlight to the driver strengths andweaknesses that they may be unaware of,for example deteriorating eyesight.The arguments against regularrefresher training: Increased cost to the individual Increased burden on driving trainers Devising an appropriate system, would itbe a test to be passed or just anassessment? No incentives to take refresher coursesOnce they have passed their driving test,drivers do not normally need to renew theirlicence until they are 70 years old. This meansthat many people drive for 50 years withoutany further training or assessment.Activityi Consider the arguments for and against a range of possible measures that could beintroduced to reduce the risk for young and novice drivers. Identify how other countries tackle these problems, whether theirmeasures are proving effective and whether they could be introducedsuccessfully in the UK.Again, RoSPA’s report,‘Young and Novice Drivers’ will provide much ofthe information required to complete these activities. There arereferences within the report to other material, much of which can beaccessed via the internet.The website, www.getinlane.com, will also be useful for all the activities in this Student Sheet.6

Drink, Drugs and Driving Student SheetBackground InformationThe role of both legal and illegal drugs in roadaccidents is complex, and does not lend itself toeasy answers. Use of illegal drugs and driving is agrowing problem. Around 18% of people killed inroad accidents have traces of illegal drugs in theirblood – a six fold increase since the mid 1980s,but 32% had a trace of alcohol. However, it is notclear what proportion of accidents, deaths andinjuries are actually caused, or partly caused, bydrugs impairing the abilities and judgment of theroad users involved.CannabisFor example, research shows that cannabis(which constitutes two-thirds of the illegal drugsdetected) affects driving behaviour for a shortperiod after being taken, resulting in a morecautious driving style; wandering about in thelane and longer decision times. However,detectable traces can stay in the body for severaldays after use, long after any impairment effecton driver performance.Roadside DetectionRoadside detection devices are being developed(although the diversity of the drugs availablemeans they will operate differently from thebreathalyser-type test). The devices will use salivaas the medium, will test for several groups ofdrugs from one specimen and will take a fewminutes to get a result. Many police forces traintheir officers to recognise the physical signs ofdrugs use and in the use of Field ImpairmentTesting to help officers decide whether to arrest asuspected drug-driver and take them to the policestation for further tests.The Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003makes it an offence to refuse to submit to thesepreliminary tests.AlcoholThe legal limit for alcohol and driving is:35 microgrammes of alcohol per 100 millilitresof breath OR 80 milligrammes of alcohol per 100millilitres of bloodDrinking and driving significantly increases thelikelihood of being involved in a crash. Even smallamounts of alcohol, well below the legal limit,increase the chances of an accident. A driver withtwice the legal limit of alcohol in the blood is atleast 30 times more likely to have an accidentthan one who has not been drinking.One in every six people killed on the roads, dies inan accident where at least one driver or rider wasabove the drink drive limit. Drink drive casualtiesaccount for 16% of all road accident deaths, 8% ofall serious injuries and 6% of slight casualties.Campaigns to deter drinking and driving havebeen running since the mid seventies. These havebeen successful, but there is now concern thatdrink driving is on the increase again. It isimportant that the drink/drive message is notlost following the recent focus on drug driving.Learning OutcomesBy completing the activities and discussionsstudents should have identified the differences indrink driving and drug driving, both in terms ofimpairment and enforcement. Students shouldhave a greater awareness of the dangers of botharising from a better understanding of the effectsof drinking and drug taking. Students should have7

shared ideas about publicity campaigns andbegun to develop an awareness of the toolsavailable to convey a message to the public.Students should have thought about targetingspecific groups when developing a campaign.Activity What do you think? iThe information can be gathered usingthe websites in the useful links sectionsplus RoSPA’s website(www.rospa.com) whichincludes a paper ondrink driving withinthe road safetysection.Create a table of illegal drugs, settingout their effects, how long the effectslast and what the law saysThe DfT sponsored website –www.drugdrive.com, providesmuch of this information.DiscussionPoints 41Consider drink driving laws and theirenforcement and then explore the drugdriving laws and how they are enforced.Find out the drink drive alcohol limit.AlcoholThe alcohol limit is enforced by the policewho conduct roadside tests using abreathalyser. If the result is positive the driveris arrested and required to take a further testat the police station. If these tests show thattheir blood alcohol or breath alcohol level isabove the limit, they are charged and willhave to attend court. There is no need for thepolice to prove that the driver was impaired,this is a legal assumption once the alcohollevel is above those set out.DrugsThere is not a legal limit for drug driving, so itis not easy to prove. The police will use DrugRecognition Techniques (observing theoutward signs of drug use) and FieldImpairment Tests (ask the driver to perform anumber of tasks, such as walk in a straightFind out about drink drivinglimits, casualties and why it is safernot to drink any alcohol at allwhen driving.line, touch their nose, etc) to help them assesswhether a driver may be impaired. If theofficer suspects the driver has taken drugs,they can require the driver to give a sample ofblood at the police station, which is thentested for drugs. However, the presence of adrug in itself will not be enough to prove theoffence of driving while unfit through drugsand the officer's evidence about poor drivingwill also be necessary. How education and publicity can warnpeople about the dangers of driving aftertaking drugs and who the target groupsshould be.One concern is that the drivers most likely tobe drug users are also those with the highestaccident risk – young drivers who areinexperienced and more likely to take risksand have poor driving attitudes. They are alsolikely to be unresponsive to ‘authoritarian’messages.The DfT Think campaign on drug drivingshows some good examples of publicitytargeted at young people, as does the work ofthe Scottish Road Safety Campaign andScottish Executive on drugs and driving.8

ActivityiDesign a drink or drugs and drivingcampaign and then implement itAgain, looking at the campaigns by theDfT and the Scottish Executive andScottish Road Safety Campaign willprovide some inspiration for thestudents.e Take it further. Report on medicines as drugs, particularly‘over-the-counter’ remedies and assess theeffectiveness of the current warninglabels. Develop a new system for labellingsuch medicationThe BUPA (www.bupa.co.uk), BMA(www.bma.org.uk) and RAC (www.rac.co.uk)websites listed in Useful links will providesome of the answers. Some of theantihistamines listed can be found in coldremedies and hayfever medication and thepackaging will say MAY cause drowsiness andyet the same substance is used in sleep aids(like Nytol) and the packaging says WILL causesleep. Such differences are clearly confusingto drivers and do not give the bestinformation possible to allow someone todecide whether to drive or not. There is asuggestion that there could be a ‘traffic light’9warning system on packaging to clearlyindicate to drivers whether they should avoiddriving completely or that it is safe to drive orthat they should be cautious about driving.

The Impact of the Media Student SheetBackground InformationThe media plays an important role in road safetyeducation. It is arguably a powerful influence onpeople’s behaviour and can massively raise theprofile of issues. The media is a very effective wayof conveying road safety publicity and educationmessages to a wide range of audiences. Thesecampaigns are usually designed to raiseawareness about particular risks and to persuaderoad users to behave in certain ways.Many adverts, films and programmes showpeople driving, riding or walking on the road.Very often the way people are shown using theroad is incidental to the storyline or characters ina programme, in which case good practice couldbe shown (for example, people could be shownwearing seat belts, crossing the road safely,wearing cycle helmets). If poor use of the road isDiscussionPoints 41Select a recent advertising campaignby a car manufacturer and discuss it,including its effectiveness. Then exploreroad safety campaigns and identifywhich techniques are more effective.Think about the moral responsibility ofTV and film makers.essential to the storyline or character,programme makers could still show the potentialconsequences of that behaviour. For example if adriver is talking on a mobile, this could be shownto result in a crash or a near miss.Learning OutcomesThe resource is designed to ‘open’ the students’eyes to the different ways that the media is usedto influence behaviour and to recognise that themedia is not always responsible in the way itshows road use.After completion of the activities and discussions,students should have a greater appreciation ofthe way in which road safety is reported andrepresented in the media and the operation ofbias within the media. Students should haveconsidered how the media can show ‘goodpractice’ in road safety, but should be able torecognise where this is not possible – forexample where irresponsible or recklessbehaviour is integral to the story line.Activity This will be a subjective discussion and willstart to make students notice the roadsafety content of TV programmes andnewspaper and magazine advertisements.Students can be encouraged to look at thework of the Office of Communications(Ofcom), whose website iswww.ofcom.org.uk. Ofcom is the regulatorfor the UK communications industries,with responsibilities across television,radio, telecommunications and wirelesscommunications services. The DfT Thinkwebsite (www.thinkroadsafety.gov.uk)shows a range of road safety publicitycampaigns. iCompile a scrapbook over several days,showing the way in which the pressdeals with road safety.Consider whether the way that issueshave been dealt with encouragespeople to be safe on the roads.Discuss the findings in a pair and thenproduce a report.The scrapbook can be compiled from localor national press, either using newspapersor the websites of local and nationalnewspapers. Stories can be downloadedfrom the internet. This activity is involvedand progresses through anumber of stages. Timemay not permit studentsto produce a report oftheir findings.10

DiscussionPoints 41Consider the use of celebrities and characters to convey road safety messageswww.thinkroadsafety.gov.uk has information about previous campaigns. RoSPA has published ahistory of drink/drive, seatbelt and speed .pdf) click on ‘Road Safety’, then ‘Advice and Information’ and ‘General road safety’).Celebrities were used in campaigns during the 1970s and 1980s to promote seat belt wearing.The DfT uses a range of tactics to get the message across, sometimes using graphic campaignimages, other times using cartoon images, for example hedgehogs, to target younger people.Activity iResearch previous road safety campaigns, plot a timeline of campaigns on drink driving,seatbelt wearing and speeding, to include casualty figures and then design a campaignand run it.RoSPA’s website (www.rospa.com/roadsafety/info/campaigns) contains material on the history ofdrink/drive, seat belt and speeding campaigns, follow the link to the road safety pages and thenlook under, advice and information – general road safety.www.dft.gov.uk contains information about transport statistics. To access statistics dating back to1950, click on ‘Transport Statistics’, then ‘Route to data’, then ‘transport accidents and casualties’then ‘casualties by type’ which will reveal a link to ‘Road Accidents and Casualties 1950-2001’.www.thinkroadsafety.gov.uk will give information on current campaigns, how they are being runand may help stimulate ideas for the students.e Take it further. Look at how a road safety issue has been portrayed in a soap opera and then produce a plotfor a soap involving a road safety message eg a crash due to a driver who was drunk, ortalking on a mobile phone.Soap operas quite often cover road safety issues. In 2003, Eastenders character Martin Fowler,mowed down and killed the character, Jamie Mitchell, whilst sending a text message on hismobile phone. In 2001, in Emmerdale, youngsters in the village driving a stolen car killedheadteacher Miss Strickland.11

Passenger Safety Student SheetBackground InformationMost children up to the age of 13 years wear seatbelts. However, from age 14, wearing seatbelts isless common. A survey by the Transport ResearchLaboratory (TRL) found that while nearly allyoung people wore their belts as front seatpassengers, they gave a variety of excuses for notwearing belts when in the back of the car, eventhough they knew it was the law to wear them.When it became compulsory in 1991 for adults towear seat belts in the back of a car, there was animmediate increase from 10% to 40% in rear seatbelt wearing. TV and radio advertising in 1993and 1994 helped to improve wearing rates butstill less than half of rear seat passengerscomplied. Since 1994, advertising (mainly TV andradio) has promoted rear seat belt wearing.By April 2004, rear seat belt wearing hadreached 66%DiscussionPoints 41Express views about seat belt wearing,find out the penalties for not wearing abelt and consider if these are sufficient.The penalties for not wearing a seat beltare usually a 30 fine issued by a policeofficer, but if the matter goes to court, thefine could be up to 500. There is anargument to say it should also be anendorsable offence, resulting in penaltypoints on the driver’slicence; this issomething thatthe studentscould be askedto discuss.In England and Wales in 2002, 126,000 fixedpenalty notices were issued, 3,000 writtenwarnings given and 4,700 people prosecuted atmagistrates' courts for failing to wear seat belts.Car passengers and particularly rear seatpassengers, need to be educated about thedangers not just to themselves but to front-seatpassengers and drivers as well. TRL estimates that155 lives a year (and 1,600 serious injuries) aresaved by the use of rear seat belts. They alsoestimate that between 8 and 15 front seatoccupants in crashes are killed by unbelted rearseat passengers every year.".Learning OutcomesBy working through the activities, studentsshould have a better understanding of how seatbelt wearing legislation emerged and the factorsthat influenced the laws being passed. Also, usingdrama techniques, students should haveconsidered and explored conflict situations,enabling them to recognise the importance ofcompromise and appreciate how peer pressuremay affect their decisions.Activity iExamine the history of seat beltlegislation and plot a timelineincluding casualties.The history of seat belt legislation can befound on www.rospa.com (click on ‘Roadsafety’,‘Advice and information’ and then‘In-car safety’).To access accident and casualty statisticsdating back to 1950, go to www.dft.gov.uk,click on ‘Transport Statistics’, select ‘Routeto data’ then ‘transport accidents andcasualties’, then ‘casualties by type’ whichwill reveal a link to ‘Road Accidents andCasualties 1950-2001’.12

Activity iExplore issues of seat belt wearing, discuss and decide what to do as the driver of a car withpassengers who don’t belt up. Write a short role play exploring this issue and th

road safety in the curriculum for KS4 and above, there is an opportunity for students to develop the skills necessary to make sensible, safe choices and enhance their personal development and safety. However, road safety is not specifically included in the curriculum and although, as a topic, it readily fits with Citizenship, it often becomes