Transcription

EXAMINING IDENTITY THEFT VICTIMIZATION USING ROUTINE ACTIVITIESTHEORYByAndrew OsentoskiA THESISSubmitted toMichigan State Universityin partial fulfillment of the requirementsfor the degree ofCriminal Justice – Master of Science2016

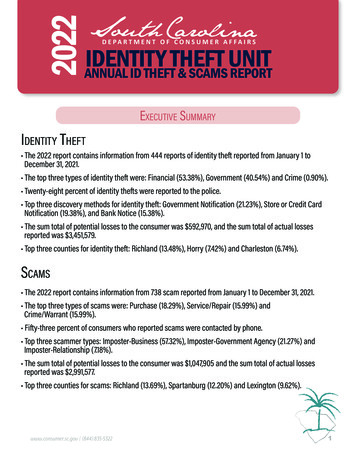

ABSTRACTEXAMINING IDENTITY THEFT VICTIMIZATION USING ROUTINE ACTIVITIESTHEORYByAndrew OsentoskiAccording the Federal Trade Commission's Consumer Sentinel Network, complaints ofidentity theft has increased from 86,250 in 2001 to 332,646 in 2014 (Consumer Sentinel NetworkData Book for January - December 2014, 2015). Monetary losses due to identity theft totaledaround 24.7 billion in 2012, though this dipped to 15.4 billion in 2014 (Harrell & Langton,2013; Harrell, 2015). This emerging problem in criminal justice should be studied. However,studying identity theft poses substantive and methodological challenges. Substantively, studiesof identity theft have been largely exploratory and have used a variety of definitions tocharacterize the crime. Due to a lack of information on offenders, low clearance rates and themultitude of ways in which identity theft can be committed both online and offline, a frameworkthat can depict patterns of offending and victimization is lacking. Methodologically,victimizations are hard to track since it is not a crime that is routinely recorded in the UniformCrime Reports. This study uses data from the 2014 National Crime Victimization Survey:Identity Theft Supplement to examine identity theft victimization. The theory of routineactivities is used as a framework to assess potential patterns and precursors of victimization.

Dedicated to my incredibly supportive family and friends, and to those no longer with uswho helped shape me into who I am today.iii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSMy thanks to:Dr. Sheila Maxwell for serving as my thesis chair and guide through this entireprocess, spending countless hours poring over my work and molding it into a respectablefinished product.Dr. Thomas Holt not only for serving on my committee, but also for sharing hisresearch and giving me the opportunity to take part in it.Dr. Mahesh Nalla for providing great constructive feedback on my work.James and Amanda, for brightening up days of hard work in the dark side of theoffice and for acknowledging me in their theses.My aforementioned friends and family whose unwavering support in the face of anumber of challenges was instrumental in the completion this work, I couldn't have done itwithout you.iv

TABLE OF CONTENTSLIST OF TABLESviLIST OF FIGURESviiChapter 1 Introduction1.1 Identity Theft12Chapter 2 Routine Activities Theory2.1 Routine Activities Theory and the Internet57Chapter 3 Online Routine Activities3.1 Target Suitability3.2 Capable Guardianship3.3 Motivated Offenders12121518Chapter 4 Methods4.1 Data4.2 Measures4.3 Suitable Targets4.4 Capable Guardianship4.5 Motivated Offenders4.6 Current Model4.7 Analytic Strategy2020222223242425Chapter 5 Results5.1Bivariate Results5.2 Multivariate Results273032CHAPTER 6 Discussion36APPENDIX41REFERENCES43

LIST OF TABLESTable 1: Scales and Descriptive Statistics29Table 2: Bivariate Analysis32Table 3: Binary Logistic Regression Model of Identity Theft Victimization Model35

LIST OF FIGURESFigure 1: Concept Diagram42

Chapter 1IntroductionIdentity theft is costly, prevalent, and it appears to be on the rise (Harrell, 2015). TheFederal Trade Commission (FTC) reports that it received over 332,000 complaints of identitytheft in 2014, up from just 86,250 in the year 2001 (Consumer Sentinel Network Data Book forJanuary - December 2014, 2015). Similarly, the National Crime Victimization Survey’s(NCVS) Identity Theft Supplement (ITS) for 2014 reports that a full 7% of U.S. residents aged16 or older were victims of identity theft, equaling about 17.6 million Americans (Harrell, 2015).The financial ramifications are just as compelling, with the monetary loss due to identity theft in2012 being an estimated 24.7 billion (Harrell & Langton, 2013). The large rise in identity theftcomplaints since 2001 coupled with the financial ramifications of this type of crime positionidentity theft as an emerging threat to the financial well-being of many Americans and theeconomy as more and more businesses expand into e-commerce. Whether it is this shift towardsmore e-commerce or another factor increasing the amount of identity theft complaints, thefinancial ramifications of the crime necessitates more research on the topic. However, studyingidentity theft poses substantive and methodological challenges. Chief among these challenges isthe ambiguity of definitions of identity theft (Reyns, 2013), the breadth of offenses that can beclassified under the identity theft umbrella (Consumer Sentinel Network Data Book for January December 2014, 2015; Lane & Sui, 2010), the lack of information on offenders (Allison,Schuck, & Lersch, 2005; Copes & Vieraitis, 2009), and the lack of theoretical framework thatcan guide research endeavors in this area.1

1.1 Identity TheftThe Department of Justice has defined identity theft as any crime in which one personuses another’s personal information fraudulently, typically for financial gain (Department ofJustice, 2015). This definition is intentionally broad to account for the breadth of offenses thatcan be classified as identity theft. The Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act of 1998defined seven general categories of identity theft: credit card identity theft, phone or utilitiesfraud, bank fraud, employment-related identity theft, government documents or benefits fraud,loan fraud, and an all-encompassing “other” category for the remaining types (Lane & Sui,2010). Under most of these categories are subcategories which further break identity theft downto specific crimes like creating new credit card accounts or fraudulently obtaining tax returns(Lane & Sui, 2010). This breadth of crimes makes identity theft difficult to study in depth.Not only are there many ways to commit identity theft, but there are many ways in whichoffenders are able to obtain information necessary to commit the crime (Copes & Vieraitis, 2009;Reyns, 2013). Identity theft was conceptualized as a white collar crime committed bytechnically skilled criminals until relatively recently. This is not necessarily the case (Allison etal., 2005; Copes & Vieraitis, 2009; Reyns, 2013). Using interviews of 59 prisoners convicted ofidentity theft, Copes and Vieraitis (2009) found that offenders come from a variety of socialclasses, occupations, and educational attainment. The authors also found that most of theinformation used to commit identity theft in these cases was not obtained online, but bought fromemployees of businesses with access to personal information (Copes & Vieraitis, 2009). Othersrummaged through personal or business mailboxes and trash cans for documents containingpersonal information (Copes & Vieraitis, 2009). This is not to say that identity theft is not alsobeing committed through high tech means.2

Although there are not many studies on high tech identity theft offenders, anecdotalevidence in the form of large scale identity theft cases confirm the existence of these types ofoffenders. A recent press release from the Department of Justice outlined an identity theft casewhich netted an offender a 15 year prison sentence. The offender hacked into U.S. businesses’computers and sold almost 2 million worth of identities in his online store which were laterused to file 65 million in fraudulent income tax returns (“Vietnamese National Sentenced to 13Years in Prison for Operating a Massive International Hacking and Identity Theft Scheme: 1,”2015). Another case involved a number of high tech techniques for stealing identities whichtargeted consumers in Massachusetts and New York. The offenders in this case gained access tounsecured networks of local businesses to install programs which gathered customer paymentinformation and sold this information online. According to court documents, the identity thiefwas able to steal in excess of 40 million credit and debit card numbers (“Leader of Hacking RingSentenced for Massive Identity Thefts From Payment Processor and U.S. Retail Networks ,”2010). While it is possible that the offenders interviewed by Copes and Vieraitis (2009) aremore representative of failed identity thieves rather than identity thieves in general, the pointremains that identity theft can be committed through both white collar and “blue collar” means.The diversity in how identity theft is committed along with law enforcement’s lowclearance rates for the crime pose a number of challenges in the study of identity theft (Allison etal., 2005). First, the low clearance rates means that virtually nothing is known about whocommits the crime (Allison et al., 2005) or exactly how particular victims are targeted. The lowclearance rate itself may be a function of the relative anonymity of the crime, where the majorityof victims themselves have no idea how offenders obtained their information in the first place, letalone a description of who stole their information (Harrell, 2015). Copes and Vieraitis’ (2009)3

study of offenders is unique at this point in time, but the offenders selected by the authors maybe representative of only low technology based identity theft. Further, the fact that theseoffenders were caught may mean that they are representative of only the least skilled in thiscategory of offenders (Copes & Vieraitis, 2009). Second, the variation in the methods employedto obtain information used to commit identity theft also implies that this crime may be morediffused and intractable. It appears that both online and offline methods are used in committingthe crime, but the extent by which online or offline techniques are used cannot be assessedwithout measures that represent both online and offline exposure.This research examines identity theft victimizations using routine activities theory. Thetheory’s focus on target suitability and guardianship are useful constructs towards understandingcontexts of victimizations. Given the lack of information about identity theft offenders, routineactivities’ focus on victims will enable a better understanding of the patterns and trends ofvictimization. This theoretical framework is also robust enough to explain both low- and hightech identity theft. As discussed above, identity theft can be committed through both high-tech(online) and low-tech (offline) methods. This duality in methods of gaining the informationnecessary to commit identity theft requires consideration of both high and low tech exposures.Important aspects of routine activities theory such as target suitability and capable guardianshipwill be operationalized using measures of both online and offline exposures and guardianship.By including explorations of both high and low tech measures in this study, a more holisticportrait of identity theft and how it may occur is expected.Data from the 2014 National Crime Survey’s (NCVS) Identity Theft Supplement (ITS)are used. The data provides a large sample of identity theft victims throughout the United Statesand is therefore useful in assessing factors that can help explain identity theft victimization.4

Chapter 2Routine Activities TheoryRoutine activities theory was conceptualized as a way to explain the uptick in crimefollowing World War II (Cohen & Felson, 1979). Social variables such as income andunemployment which other theories use to explain high crime rates were actually improvingwhile the crime rate rose (Cohen & Felson, 1979). In order to explain this phenomenon, Cohenand Felson (1979) proposed that the crime spike was not a function of differences in offenderbehavior, but rather a difference in victim behavior. Cohen and Felson (1979) were able to distillthis thought down to a simple concept: crime occurs as an interaction of (1) motivated offenders,(2) suitable targets, and (3) a lack of capable guardianship. Simply put: where offenders, targetswith resources that offenders desire, and a lack of oversight meet, crime is more likely to occur(Cohen & Felson, 1979). Thus routine activities theory was born.Cohen and Felson (1979) tested their newly proposed theory using a few measures todetermine whether shifts in victim behavior actually occurred, and what these were. A fewmajor shifts in the routine activities of Americans that Cohen and Felson (1979) identified wereincreases in female college students, households unattended during business hours, out of towntravel, vacations, and vacation time given to employees (Cohen & Felson, 1979). Coincidingwith these behavioral changes was an increase in the number of households and thereforehousehold consumer goods such as televisions and other electronics (Cohen & Felson, 1979).These consumer products were also becoming increasingly lightweight and portable as thetechnology behind them improved, increasing the ease with which a burglar could walk out thedoor with a new television (Cohen & Felson, 1979). Cohen and Felson (1979) asserted that theseshifts made people more vulnerable to offenders outside the home because of increased exposure5

while simultaneously making homes more vulnerable to burglary during the day (Cohen &Felson, 1979).The basic test of whether the changes in routine activities had an effect on crime trends inthe way Cohen and Felson (1979) expected lies in differential rates of change within crimecategories. For example, given that people are out of the safety of their homes more often, anincrease in the rate of victimization at the hands of strangers, not people known to the victim,should be expected (Cohen & Felson, 1979). Similarly the rates of daytime burglary shouldincrease at a rate higher than that of night time burglary given the change in the amount ofhouseholds unoccupied during the day. Indeed, this is exactly what Cohen and Felson (1979)observed. Lifestyle changes which decreased capable guardianship and increased targetsuitability appears to have led to very real change in crime trends (Cohen & Felson, 1979).Since the inception of routine activities theory, it had been used to study crimes whichoccur when targets and offenders meet in a physical space. At the time that Cohen and Felson(1979) created routine activities, the overwhelming majority of crime occurred with perpetratorsand victims in the same physical space, or at least the perpetrator taking physical property.Studies have generally supported the applicability of routine activities to larceny and otherproperty crimes (Franklin, Franklin, Nobles, & Kercher, 2012; Johnson, Yalda, & Kierkus, 2010;Mustaine & Tewksbury, 1998) with others supporting the application of the theory to moreserious property crimes including motor vehicle theft (Lee & Alshalan, 2005). However, sincethe emergence of the internet and its rapid popularization in the late 1990s, crime in whichvictims and perpetrators never come into physical contact have become more viable (Janus &Davis, 2005).6

2.1 Routine Activities Theory and the InternetAs previously mentioned, there are both online and offline methods for obtaining theinformation needed to commit identity theft. The applicability of routine activities theory tooffline methods is easy to see. In order to commit identity theft through offline means a potentialoffender simply needs to gain access to the victim’s personal information. This process typicallyresembles other types of crime which requires physical access to a victim’s property, namelyburglary or other types of theft (Copes & Vieraitis, 2009; Newman, 2004). Theft of purses orwallets is not uncommon (Newman, 2004), and interviews with individuals convicted of identitytheft offenses by Copes and Vieraitis (2009) revealed that other offenders searched throughgarbage cans or mailboxes for mail or other documents containing personal information.Methods of attaining personal information which rely on physical access to documents orgovernment issued identification can be viewed through routine activities theory which stresses alack of capable guardianship and suitable targets - in some cases easily accessible garbage cansand mailboxes. Cases which involve breaking into either homes or cars to steal personalinformation are very similar to the types of property crimes Cohen and Felson (1979) originallyendeavored to explain with routine activities theory (Copes & Vieraitis, 2009). That being saidthis comparison is not perfect. An extra step of converting identities into financial gain isnecessary to commit identity theft. The connection between online routine activities and identitytheft is less clear. The current study aims to apply core concepts of offline routine activities toonline activities to explore whether online activities can explain identity theft victimization.The internet has changed the lifestyle of the average person significantly and in a mannerthat is not dissimilar to the way American lifestyles changed post-WWII (Reyns, 2013). The2003 United States Census data revealed that 62% of American households owned a computer7

with 54.7% reporting internet use (Janus & Davis, 2005). The same survey found 18% of adultsused the internet for banking, and about 32% had purchased a product online (Janus & Davis,2005). Ten years later, the 2013 United States Census found major shifts in how Americanswere using computers and the internet with 83.3% of households reporting computer ownershipand 74.4% reporting internet use (File & Ryan, 2014). Not only did the number of Americansusing computers and internet change, but so too did the ways in which these technologies areused.A 2013 Pew Research Center survey found that 51% of U.S. adults now use the internetfor banking (Fox, 2013). Other uses for the internet including communication and data storageare on the rise as well (“Cisco Global Cloud Index: Forecast and Methodology, 2013–2018,”2014; Leavitt, 2005). As our reliance on technology steadily increases, it is likely that moreactivities that were once conducted in person will shift to cyber space (Fletcher, 2007; Reyns,Henson, & Fisher, 2011; Reyns, 2013). For example, the most recent report on e-commercesales in the United States show that online sales account for just under seven percent of totalretail sales for the country in 2015, an increase from just under three percent in 2006 (DeNale,Liu, & Weidenhamer, 2015). By the same token Gartner, an information research company,predicts that at least 50% of all Global 1000 companies will have sensitive customer data storedin a public cloud by 2016 (Pettey & van der Meulen, 2011). Similar to the way the averageAmerican was more exposed to potential crime based on patterns of behavior post-WWII, therise of online activities seems to have increased the exposure of the average American tovictimization through the internet (Fletcher, 2007; Reyns et al., 2011; Reyns, 2013).This shift in routine activities has led criminologists to expand routine activities theory toinclude offenses which occur without direct physical contact between offenders and targets8

(Choi, 2008; Eck & Clarke, 2003; Holt & Bossler, 2009; Pratt, Holtfreter, & Reisig, 2010; Reynset al., 2011; Reyns, 2013; Ricketts, Higgins, & Marcum, 2010). Eck and Clarke (2003) makethis expansion by including disparate networks as places of convergence between offenders,suitable targets, and a lack of capable guardianship. In this formulation of the theory, offendersand targets are connected through some type of network, such as the postal service or the internet(Eck & Clarke, 2003). The network can be a substitute for physical locations where offendersand targets meet and in which crime occurs. Eck and Clarke (2003) propose this conceptualexpansion to explain crimes like mail bombing, telemarketing fraud, and online identity theft. Inthis formulation of the theory, offenders and targets are connected through some type of network,such as the postal service or the internet (Eck & Clarke, 2003). This extension of routineactivities theory has been used in a number of studies since the boom in the popularity of theinternet (Choi, 2008; Eck & Clarke, 2003; Holt & Bossler, 2009; Pratt et al., 2010; Reyns et al.,2011; Reyns, 2013, 2015; Ricketts et al., 2010).This is not to say that this formulation of routine activities theory is without its problems.Yar (2005) outlines a number of issues with using the theory in online contexts. Chief amongYar’s (2005) concerns is the reliance of routine activities theory on the spatial relationshipbetween offenders and targets - the internet is fundamentally different from the physical world inthe sense that on the internet it is very easy to get from one site to another. In other words,spatial divergence in the physical world acts as an important mediator to crime. Targets andoffenders must be on the same street or in the same building. Online, many targets may be just afew clicks away from offenders even if the two are physically thousands of miles apart, makingconvergence much easier on the internet (Yar, 2005).Yar’s (2005) second concern about extending routine activities theory to online crime9

concerns the theory’s main supposition that crime occurs within the convergence of motivatedoffenders, suitable targets and a lack of capable guardianship at a moment in time. People are onthe internet at many different times and in many different contexts. Therefore Yar (2005) arguesthat there really is no one ‘time’ that offenders can target a victim. For instance, a phishingemail does not exist only at a particular moment. An offender might send the email and get aresponse a week later. In contrast, a physical theft occurs at a defined time when the offendergains access to a target.Finally, Yar (2005) calls into question whether the targets of online crime can beevaluated for suitability using the “VIVA” acronym mentioned by Cohen and Felson (1979).VIVA describes the dimensions outlined by Cohen and Felson (1979) to evaluate the suitabilityof physical targets. These are: value, inertia, visibility, and accessibility (Cohen & Felson, 1979;Yar, 2005). Value represents how much an item or multiple items are worth. The concept ofinertia concerns how cumbersome a physical object might be to take. Visibility refers to the easewith which an offender can physically observe the target – it is difficult to target something ifone does not know it is there. Accessibility refers to how easy it is to get to and from a target(Yar, 2005). VIVA is largely easy to apply to physical objects, but it is not so simple to apply toonline targets (Yar, 2005).Cohen and Felson’s (1979) original intent with the VIVA construct was to explain whatmight put an item or person at risk for crime in a physical space. While there are few studieswhich have explicitly applied dimensions of VIVA to online targets (Choi, 2008; Holt & Bossler,2009) there have been a number of studies which have applied similar elements (Copes, Kerley,Huff, & Kane, 2010; Holt & Turner, 2012; Pratt et al., 2010; Reyns et al., 2011; Reyns, 2013;Ricketts et al., 2010). For example, while Copes et al. (2010) were not specifically testing10

VIVA, their study of fraud and identity theft did include a measure of Internet use frequencywhich can be viewed as a measure of visibility for online crimes. There are many challenges toovercome in explicitly expanding VIVA to online targets (Yar, 2005). The discussion assesseshow routine activities theory has been and may be applied to online routine activities. WhileYar’s (2005) concerns regarding the use of routine activities theory in the study of online crimeare reasonable, routine activities has been shown to be of use beyond only physical crime.To date, research on identity theft has been largely exploratory in nature (Benson, 2009;Copes & Vieraitis, 2009; Higgins, Hughes, Ricketts, & Wolfe, 2008; Lane & Sui, 2010; Slosarik,2002). Recently, however, a small number of researchers have examined the applicability oflifestyles oriented theories in the study of fraud and identity theft victimization (Pratt, Holtfreter,& Reisig, 2010; Reyns, 2013) despite the concerns Yar (2005) raises in order to determine theutility of the theory in this area. These studies are important in leading the shift from what arepredominantly atheoretical and descriptive explorations of identity theft to one that includes atheoretical framework. Routine activities theory has been used as the leading framework amongthese lifestyle oriented approaches towards better understanding identity theft victimization.11

Chapter 3Online Routine ActivitiesGiven its original conception as a theory focused on physical crime it is important toconsider the ways in which the elements of routine activities theory have been applied to onlineactivities. The discussion below assesses how the elements of routine activities theoryspecifically target suitability, capable guardianship, and motivated offenders have been used instudies of online crime.3.1 Target SuitabilityA number of studies regarding a variety of online crimes have been conducted and haveoperationalized target suitability in different ways (Choi, 2008; Copes et al., 2010; Holt &Bossler, 2009; Holt & Turner, 2012; Pratt et al., 2010; Reyns et al., 2011; Reyns, 2013, 2015;Ricketts et al., 2010). Using the VIVA components of target suitability, we will first look intoways other studies have operationalized a target’s value in an online context. The value oftargets in online crime is heavily dependent on the type of offense being perpetrated (Copes etal., 2010; Pratt et al., 2010; Reyns et al., 2011). For example, the targets of expressive crimessuch as cyber stalking or harassment cannot be readily “valued”. Reyns et al. (2011) attemptedto create a scale of target attractiveness in their study of cyber stalking based on the amount andtypes of information available on potential targets such as a full name, an e-mail address, photos,videos, and sexual orientation, among other measures. Value in other online crimes includingidentity theft would seem to be largely invariant across potential targets – that is, one identitywould not be more valuable than the next. However, the findings of Copes et al. (2010) andReyns (2013) suggest that higher income individuals are more likely to experience identity theft.The authors suggest this might be due to a difference in exposure, although the effects of income12

in Reyns’ (2013) study remained significant when lifestyle factors were controlled (Copes et al.,2010; Reyns, 2013). Still, most studies of identity theft do not include measures of value as itwould be difficult for offenders to assess the relative value of any given identity over another.Inertia is another portion of target suitability that is common to most potential targets inonline crimes. Yar’s (2005) conceptualization of inertia in the context of stealing data includesfile size, with larger files being more difficult to copy on underpowered machines or across slowinternet connections. That being said Yar (2005) acknowledges that these limitations are notsignificant for most and a criminal may actually prefer the larger file if it includes moreinformation. Again, Reyns et al.’s (2011) study of cyberstalking reasoned that inertia might beencapsulated in the amount and type of information included in a potential target’s online socialprofile. More information or certain types of information may be more attractive to potentialoffenders because they facilitate cyberstalking better than others (Reyns et al., 2011). Forexample, a profile with information linking to other social media accounts and a full name maybe akin to the lighter televisions of today in terms of inertia for physical crimes, while an accountwith only photos might represent a target more similar to a bulky older tube television (Cohen &Felson, 1979; Reyns et al., 2011). Much like the relative physical ease of stealing a modern flatscreen television versus a heavy older television, cyber stalking a victim with more publiclyavailable information is much easier than cyber stalking someone without a wealth ofinformation (Cohen & Felson, 1979; Reyns et al., 2011).The concept of inertia has not been measured in studies of identity theft as it is not easilyquantifiable. It might be the case that inertia in the case of online identity theft would be relatedto whether it is easy to gather information from a large database or if the collection process ismore tedious. For offline variants of identity theft, inertia similarly does not seem like a large13

hurdle. Inertia does not seem to be a factor in stealing wallets, purses, or documents (Copes &Vieraitis, 2009).As Yar (2005) argues, target visibility in online routine activities might be more difficultto assess. The internet is by its very nature a very public network (Wall, 2008; Yar, 2005).Ricketts et al. (2010) included a question about whether respondents marked their socialnetworking profile as ‘private’ in their study of online victimization. Other studies have notincluded an explicit measure of target visibility but did include items concerning what types ofonline behaviors the respondent performed or the time spent online (Choi, 2008; Holt & Bossler,2009; Pratt et al., 2010; Reyns et al., 2011; Ricketts et al., 2010). A complication to theapplicability of target visibility to identity theft is that businesses themselves can also be targetsfor data leaks, not just individuals (2015 Cost of Data Breach Study: United States, 2015). In thecase of a large scale data breach the routine activities of an individual are not as importantoutside of the businesses they frequent.Accessibility may be the most difficult element to assess in porting routine activities toonline behaviors. Computer based techniques for gathering personal information necessary tocommit identity theft range from technically s

EXAMINING IDENTITY THEFT VICTIMIZATION USING ROUTINE ACTIVITIES THEORY By Andrew Osentoski According the Federal Trade Commission's Consumer Sentinel Network, complaints of identity theft has increased from 86,250 in 2001 to 332,646 in 2014 (Consumer Sentinel Network Data Book for January - December 2014, 2015). Monetary losses due to identity .