Transcription

Person-Centered,Outcomes-Driven Treatment:A New Paradigm for Type 2 Diabetesin Primary CareCONTRIBUTING AUTHORSSTEWART B. HARRIS, CM, MD, MPH, FCFP, FACPMProfessor, Departments of Family Medicine, Medicine, andEpidemiology and BiostatisticsDiabetes Canada Chair in Diabetes ManagementIan McWhinney Chair of Family Medicine StudiesSchulich School of Medicine and DentistryWestern UniversityLondon, Ontario, CanadaALICE Y.Y. CHENG, MD, FRCPCAssociate Professor, Department of Medicine,Division of Endocrinology and MetabolismUniversity of TorontoToronto, Ontario, CanadaMELANIE J. DAVIES, CBE, MBChB, MD, FRCP,FRCGP, FMedSciProfessor of Diabetes MedicineUniversity of Leicester andHonorary Consultant PhysicianUniversity Hospitals of Leicester NHS TrustLeicester, UKHERTZEL C. GERSTEIN, MD, MSc, FRCPCProfessor, Department of Medicine and Department ofHealth Research Methods, Evidence, and ImpactMcMaster-Sanofi Population Health Institute Chair inDiabetes Research & CareDeputy Director, Population Health Research InstituteDirector, Diabetes Care and Research ProgramPopulation Health Research InstituteMcMaster University and Hamilton Health SciencesHamilton, Ontario, CanadaJENNIFER B. GREEN, MDProfessor of MedicineDivision of Endocrinology andDuke Clinical Research InstituteDuke University Medical CenterDurham, NCNEIL SKOLNIK, MDProfessor of Family and Community MedicineSidney Kimmel Medical CollegeThomas Jefferson UniversityPhiladelphia, PA, andAssociate Director, Family Medicine Residency ProgramAbington Jefferson HealthAbington, PAThis publication has been supported by unrestricted educational grants to theAmerican Diabetes Association from Eli Lilly and Company and Novo Nordisk.2020

Person-Centered, Outcomes-DrivenTreatment: A New Paradigm for Type 2Diabetes in Primary Care is published bythe American Diabetes Association, 2451Crystal Drive, Arlington, VA 22202. Contact:1-800-DIABETES, professional.diabetes.org.The opinions expressed are those of theauthors and do not necessarily reflect thoseof Eli Lilly and Company, Novo Nordisk, orthe American Diabetes Association. Thecontent was developed by the authors anddoes not represent the policy or position ofthe American Diabetes Association, any of itsboards or committees, or any of its journals ortheir editors or editorial boards. 2020 by American Diabetes Association.All rights reserved. None of the contentsmay be reproduced without the writtenpermission of the American DiabetesAssociation. To request permission to reuseor reproduce any portion of this publication,please contact permissions@diabetes.org.Front and back cover imageCredit: Mehau Kulyk/Science Source;Description: Torso blood vessels. Historicalartwork of a human torso that has beendissected to show major blood vessels(arteries and veins, both red).

Person-Centered,Outcomes-DrivenTreatment:Stewart B. Harris, CM, MD, MPH,FCFP, FACPM1A New Paradigm for Type 2Diabetes in Primary CareNeil Skolnik, MD8,9Alice Y.Y. Cheng, MD, FRCPC2Melanie J. Davies, CBE, MBChB,MD, FRCP, FRCGP, FMedSci3,4Hertzel C. Gerstein, MD, MSc,FRCPC5Jennifer B. Green, MD6,7ABSTRACT Primary care providers are well-positioned to help patientswith type 2 diabetes achieve glycemic control while reducing theirrisks of serious complications such as atherosclerotic cardiovasculardisease, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease. Recent outcomestrials of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists and sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors have revealed that these agentsoffer cardiorenal benefits beyond their glucose-lowering effects. TheAmerican Diabetes Association and the European Association for theStudy of Diabetes now recommend a person-centered approach totype 2 diabetes treatment through which a patient’s multimorbidities,preferences, characteristics, and barriers are considered alongside A1Cin individualizing the diabetes management plan. Here, we review theevidence supporting this guidance and describe how to implement thenew holistic approach. Research has demonstrated the potential foroffering a continuum of benefit from primary through tertiary preventionof microvascular and macrovascular disease while also achievingglycemic targets. The new outcomes-based guidelines provide aroadmap for integrating this newfound knowledge into clinical practice.1Schulich School of Medicine andDentistry, Western University, London,Ontario, Canada2Type 2 diabetes affects approximately 90% of the estimated 463 millionpeople diagnosed with diabetes worldwide (1). In the United States, about 12%of the population has diabetes, about one-fourth of whom are undiagnosed(2), and the direct and indirect costs of diabetes were estimated to be 327billion in 2017 (3). People living with diabetes are at higher risk of long-termcomplications, with increased morbidity and premature mortality (4). Nearlyone-third of people with type 2 diabetes have atherosclerotic cardiovasculardisease (ASCVD), encompassing myocardial infarction (MI), unstable angina,stroke, and peripheral arterial disease. Diabetes also conveys increased risksof several microvascular complications such as eye, nerve, and foot conditionsand is one of the most common causes of chronic kidney disease (CKD) (5),which affects 20–40% of people with diabetes, often leading to end-stagerenal disease (ESRD) (6–10). A comprehensive and multifactorial treatmentapproach that starts at diagnosis and widens to address a continuum ofrisk over the course of a patient’s lifetime is essential to mitigate the excessmorbidity and mortality associated with diabetes. Primary care providers(PCPs) are uniquely positioned to offer people with type 2 diabetes acontinuum of care that matches the continuum of risk from primary throughtertiary prevention of microvascular and macrovascular complications.Department of Medicine, Division ofEndocrinology and Metabolism, Universityof Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada3University of Leicester, Leicester, UK4University Hospitals of Leicester NHSTrust, Leicester, UK5Population Health Research Institute,McMaster University and Hamilton HealthSciences, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada6Division of Endocrinology, DukeUniversity Medical Center, Durham, NC7Duke Clinical Research Institute, DukeUniversity Medical Center, Durham, NC8Sidney Kimmel Medical College, ThomasJefferson University, Philadelphia, PA9Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, PAAddress correspondence toStewart B. Harris,Stewart.Harris@schulich.uwo.ca. 2020 by the American DiabetesAssociation, Inc.

The latest American Diabetes Association (ADA)/European Association for the Study of Diabetes(EASD) consensus guidelines on hyperglycemiamanagement and the ADA’s Standards of Medical Carein Diabetes—2020, which incorporate the ADA/EASDguidelines, recommend an approach that represents aparadigm shift in the management of type 2 diabetes(11–15). The most dramatic difference betweenthese guidelines and their earlier iterations is thatthe traditional “glucocentric” strategy, emphasizingA1C-lowering as the primary consideration in therapyselection, has given way to a more expansive approachthat seeks to tailor the pharmacotherapeutic regimen tothe specific needs of each patient.Although these guidelines describe the new approachas “patient-centered,” some have advocated a transitionto “person-centered” (16,17), which we will use hereto emphasize the holistic nature of the new paradigm.The person-centered approach allows and encouragesclinicians—especially PCPs who treat the vast majority ofpeople with type 2 diabetes—to take issues other than A1Cinto account in a shared decision-making process withtheir patients. Presence or high risk for ASCVD, CKD, andheart failure (HF), as well as patients’ needs, preferences,sociodemographic characteristics, access limitations,and financial barriers, all now take a place alongside A1Cas key considerations in designing the most appropriatediabetes management plan for each patient.This substantial change in approach resulted, in largepart, from an explosion in available antidiabetic medications during the past decade. The ever-expanding therapeutic armamentarium, which now includes multipleagents in 12 different drug classes (11,12), has thepotential to overwhelm clinicians and has likely contributed to therapeutic inertia and therapeutic nihilism(18–20). However, recent cardiovascular outcomestrials (CVOTs), particularly those conducted withglucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists andsodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors,have helped to refocus diabetes clinical practice in newand exciting ways. The dramatic results of these trialshave provided evidence not only of the cardiovascularsafety of these agents, but also of their potentially lifeand organ-saving benefits (21,22). Although metformincontinues to be the preferred initial glucose-loweringpharmacotherapy in type 2 diabetes, ADA and EASDnow recommend a GLP-1 receptor agonist, an SGLT2inhibitor, or both as add-on therapies in patients with orat high risk for ASCVD, CKD, or HF.The key CVOTs that have informed these recommendations and their clinical implications are reviewed inthis monograph. This timely publication also providesan opportunity for PCPs to better understand the newholistic approach to managing type 2 diabetes. We focuson how the latest ADA/EASD consensus guidelinesand ADA Standards of Care set out a strategy that isboth relevant and uniquely suited to primary care. Weinclude a detailed description of this new strategy and itsrationale and summarize the key evidence supporting it.Although type 2 diabetes management is moving awayfrom the strictly glucocentric stepwise algorithm of thepast, early glucose control remains important, and weexplain where and how attaining individualized A1Ctargets fits into this more expansive approach.An Approach Made forPrimary CareKEY POINTS» PCPs may experience difficulty in staying abreastof rapid advancements in knowledge of andtreatments for type 2 diabetes, which couldcontribute to therapeutic inertia.» Clinical trials of new medications, once focusedon the surrogate endpoint of A1C, now yield awealth of data on actual clinical events associatedwith diabetes complications.» Type 2 diabetes management has evolvedfrom a glucocentric to a more holistic, personcentered approach.With more than 1.5 million cases diagnosed annually (2) and a myriad of available medications andtreatment strategies, type 2 diabetes is both the mostcommon and the most complicated chronic diseaseencountered daily in primary care. Numerous factorscontribute to high rates of diabetes, including a highprevalence of obesity, predispositions based ongenetics and race/ethnicity, and social determinantsof health. For example, the prevalence of diabetes is60% higher among non-Hispanic blacks and people ofHispanic ethnicity than among non-Hispanic whites,and 12.6% of U.S. adults with less than a high schooleducation have diagnosed diabetes compared to 7.2% ofthose with a higher education level (2).The consequences of these inequities are serious,because the consequences of having diabetes are2 Person-Centered, Outcomes-Driven Treatment: A New Paradigm for Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care

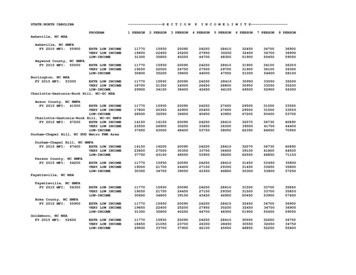

serious. Diabetes was the seventh leading cause ofdeath in 2017, contributes to mortality from four ofthe six other most common causes of death, more thandoubles a person’s cardiovascular risks, and contributes to increased risks of cancer and dementia (23–27).A dramatic increase in the prevalence of diabetes inthe past 40 years has resulted in diabetes truly being a“primary care disease.” Diagnosed diabetes in the UnitedStates increased from about 2.5% of the population in1980, to nearly 4.5% in 2000, to its current rate of 10%(Figure 1) (28). There simply are not enough diabetesspecialists to provide care for the vast majority of thesepatients; thus, PCPs have become, and will continueto be, the clinicians who provide most of the care forpatients with type 2 diabetes in the United States.accounting for more than 20 new medications andnumerous products combining drugs from differentclasses (Figure 2) (30). More than 560 additionaldiabetes-related medications are in development (31).It is no wonder that PCPs have found it extremelychallenging to stay current with the rapid advancementin pharmacologic therapy for type 2 diabetes (18).FIGURE 2 Introduction of type 2 diabetes medications inthe United States. Adapted from ref. 30.FIGURE 1 Number and percentage of U.S. population withdiagnosed diabetes, 1958–2015 (28).THE DIABETES KNOWLEDGE EXPLOSION ANDITS RELEVANCE FOR PRIMARY CAREFew areas of medicine have changed as much in thepast 20 years as the field of diabetes. Most clinicianspracticing today were taught that type 2 diabetes wasthe direct result of reduced insulin secretory capacityof the pancreas in combination with increasing peripheral insulin resistance. In 2009, the term “ominousoctet” was used to describe the eight different organsystems—brain, intestine, adipose tissue, kidney,muscle, liver, and pancreatic α- and β-cells—thatcontribute to diabetes and are therefore therapeutictargets for its treatment (29). Most of these aspectsof diabetes pathophysiology were unknown when themajority of today’s clinicians attended medical school.Until the mid-1990s, only two drug classes wereavailable in the United States for the treatment oftype 2 diabetes: insulin and sulfonylureas. Since then,10 new classes of medications have come to market,The Danger of Therapeutic InertiaThe sheer number of available medications can lead touncertainty about which ones to choose for any givenpatient, which in turn can result in therapeutic inertia(32). “Therapeutic inertia” refers to the lack of timelyadjustment to the treatment regimen when a patient’stherapeutic goals are not met (19). This concept isimportant because about half of patients with diabetesdo not meet a general A1C target of 7% (a proportionthat has remained constant for more than a decadedespite numerous therapeutic advances [33]), andfailure to attain a target A1C increases the likelihoodof developing complications (34). Therapeutic inertiaoccurs throughout the course of diabetes management,from initiation of the first antihyperglycemic agentto intensification of insulin to deintensification ofthe treatment regimen when called for, leaving manypatients with poor glycemic control or at undue risk forlong periods (19,35,36).Many factors contribute to therapeutic inertia at thepatient, provider, and health system levels (19). Onemajor issue for PCPs is the challenge of staying up todate with the burgeoning number of diabetes medications. The social sciences literature suggests that havingmany choices can lead to “decision paralysis” (37); forclinicians, it can lead to either doing nothing or simplyprescribing the medications they are most used to ratherthan the best medications for a given patient.Person-Centered, Outcomes-Driven Treatment: A New Paradigm for Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care 3

Examinations of prescribing patterns have yieldedfindings that reflect therapeutic inertia. For example, arecent exploration of real-world prescribing patterns for 1 million people with diabetes (38) showed that 77%of patients were initially started on metformin. Duringa mean follow-up of 3.4 years after starting metformin,48% of these patients began taking a second antidiabeticmedication, at a mean A1C of 8.4%. The most commonlyprescribed second agent was a sulfonylurea, accountingfor 46% of second-line agents.Sulfonylureas have a clear place in the treatment oftype 2 diabetes as effective low-cost agents; however,their drawbacks, specifically their association withweight gain and increased hypoglycemia, make thema suboptimal choice for many patients compared toagents in newer drug classes. Many nonsulfonylureamedications have a lower incidence of hypoglycemia andare either weight neutral or promote weight loss. Also, aspreviously mentioned, newer GLP-1 receptor agonistsand SGLT2 inhibitors offer substantial benefits withregard to cardiovascular and renal outcomes, makingthem important options for the sizeable proportionof people with diabetes who also have cardiovasculardisease (CVD), CKD, or both.SURROGATE ENDPOINTS VERSUSCLINICAL EVENTSAnother important development in the past two decadeshas been the recognition of the difference betweensurrogate endpoints and real clinical events (39). Asurrogate endpoint is a measurable effect used in clinicaltrials to represent the true clinical benefit of a medication. Although a surrogate endpoint is not an actualclinical event of interest, it serves as an alternative, orsurrogate, meant to represent the event of interest.The prime example in diabetes is the traditional useof A1C as a surrogate endpoint in the assessment of theeffectiveness of diabetes drugs, with the assumption thatsufficiently lowering A1C would lead to reductions in thedevelopment of long-term complications. Thus, the focuswas on a drug’s efficacy in lowering A1C—not on whetherit actually reduced the number of clinical events relatedto diabetes complications. What clinicians and peoplewith diabetes really care about, however, is decreasingthe likelihood of developing complications over time (i.e.,primary prevention). The landmark Diabetes Control andComplications Trial in patients with type 1 diabetes (40),published in 1993, was the first study to demonstratethe link between glycemic control and microvasculardisease. In 1998, the U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study(UKPDS) (41) confirmed that intensive glucose-loweringalso reduced microvascular complications in type 2diabetes. A decade later, 10-year follow-up data from theUKPDS showed that intensive therapy to reduce hyperglycemia also reduced macrovascular complications (42),and a macrovascular benefit was also found after 17 yearsin the DCCT’s type 1 diabetes observational follow-upcohort (43).Recognizing the difference between surrogate andclinical endpoints, research trials of new diabetesmedications began to be designed to measure actualclinical outcomes, including cardiovascular events andCKD progression. Consistent with and furthering thisfocus, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)in 2008 issued a seminal statement of guidance to thepharmaceutical industry that would change the courseof diabetes pharmacotherapeutic research and development (44). The FDA called for industry to conductlong-term CVOTs to establish the cardiovascular safetyof new diabetes drugs. Whereas previous drug trials hadaimed to demonstrate efficacy in lowering the surrogateendpoint of A1C, from 2008 on, new medications wouldneed to be proven as safe as placebo with regard to actualcardiovascular events to earn FDA approval.NEWER DIABETES MEDICATIONS REDUCECLINICAL EVENTSAs will be discussed in greater detail elsewhere inthis monograph (p. 12 and p. 16), recent CVOTs haveprovided important new evidence that improvedoutcomes—specifically the prevention or delay of cardiovascular and renal disease—may be determined not onlyby the degree of A1C reduction achieved, but also by thechoice of agents used to achieve that reduction.Agents from three new drug classes—dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, SGLT2 inhibitors, and GLP-1receptor agonists—have come to market since the FDAissued its guidance, all having been evaluated in rigorousCVOTs. Trials of the DPP-4 inhibitors all demonstratedcardiovascular safety compared to placebo, but nonedemonstrated superiority over placebo (i.e., cardiovascular benefit) (45–48). However, trials of several SGLT2inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists have not onlyproven their cardiovascular safety, but also demonstratedthe beneficial effects of reducing major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), hospitalization for HF (HHF),and/or progression of CKD. Meta-analyses of thesetrials (21,22,49) suggest that agents from both classes4 Person-Centered, Outcomes-Driven Treatment: A New Paradigm for Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care

reduce the risk of MACE by 11–12% in patients with type2 diabetes and established ASCVD. SGLT2 inhibitorsalso reduce the risk of HHF by 31%, whereas GLP-1receptor agonists have no significant effect on HHF.Agents from both classes reduce the risk of progressionof CKD, including macroalbuminuria, but only SGLT2inhibitors have demonstrated a reduction in the riskof a renal composite including worsening estimatedglomerular filtration rate (eGFR), ESRD, and renal death(hazard ratio [HR] 0.55, P 0.001) (21,49). Whereas theglucose-lowering effects of SGLT2 inhibitors are bluntedat an eGFR 45 mL/min/1.73 m2, the renal and cardiovascular benefits have been seen down to an eGFR of30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (50). It is unclear whether usingagents from both drug classes in combination wouldprovide an additive cardiovascular benefit, although theuse of such combinations has been studied (51,52).EVOLUTION OF CLINICAL PRACTICERECOMMENDATIONSThe recent significant expansion of the evidencebase for the treatment of type 2 diabetes has led inturn to frequent updates to guidelines for managinghyperglycemia. Recent clinical practice guidelineshave moved from the glucocentric model to a moreperson-centered approach that matches the individualized needs of patients and their existing comorbiditiesto the characteristics and benefits afforded by specificmedications (11–15).In 2009, ADA and EASD published their first consensusreport on the medical management of hyperglycemia intype 2 diabetes (53). The evidence has changed so rapidlyin recent years that it is hard to believe it has only been adecade since these guidelines stated:Except for their differential effects onglycemia, there are insufficient data at thistime to support a recommendation of oneclass of glucose-lowering agents, or onecombination of medications, over otherswith regard to effects on complications. . . In other words, the salutary effects oftherapy on long-term complications appearto be predicated predominantly on the levelof glycemic control achieved rather than onany other specific attributes of the intervention used to achieve glycemic goals.In 2012, and again in 2015, joint ADA/EASD positionstatements were published calling for a person-centeredapproach (54,55). These guidelines delineated fivemedication characteristics—efficacy, hypoglycemia risk,effect on weight, side effects, and cost—that cliniciansshould take into consideration when deciding whichmedication to use after initial treatment with metforminfor a given patient.The latest ADA/EASD consensus report, simultaneously published in the United States and Europe in 2018(11,12) and updated at the end of 2019 (13,14), has furtherrefined the personalized approach to diabetes management. By integrating the latest evidence from CVOTs,the consensus committee clarified and expanded onfactors clinicians should consider in seeking to matchmedication choices to patients’ specific needs. ADA, inturn, incorporated these recommendations into its 2020Standards of Care (15).This person-centered approach can guide cliniciansin selecting wisely from available medications. It shouldalso help to reduce therapeutic inertia secondary to clinical uncertainty regarding the wealth of options to helppatients optimize their glycemic control. Based on thecollective evidence on actual clinical events from CVOTs,the latest guidelines provide a roadmap for selecting theright medication at the right time for each patient.A New Approach for aNew Era: The Case forPerson-Centered CareKEY POINTS» A person-centered approach that addressespatients’ multimorbidities, needs, preferences,and barriers and includes diabetes education andlifestyle interventions as well as pharmacologictreatment is essential to effective diabetesmanagement.» Selection of add-on therapy after metforminshould be based not only on a patient’s A1C, butalso on the presence of comorbidities such asASCVD, HF, and CKD, as well as the patient’sclinical characteristics, risks for side effects, andsocioeconomic factors.Management of type 2 diabetes has become increasingly complex. As previously noted, numerous newdrug classes have entered the market. Furthermore,the disease not only affects people from many culturesand diverse backgrounds, but now increasinglyaffects younger as well as older people (56). It is alsoPerson-Centered, Outcomes-Driven Treatment: A New Paradigm for Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care 5

associated with multimorbidity (57). Thus, individualswith diabetes face diverse life challenges, requiringclinicians to adopt a personalized approach whendelivering care. Additionally, the focus of care hasexpanded far beyond glucose-lowering alone and nowincludes the need to manage comorbid conditions suchas obesity, ASCVD, and CKD (58), while also addressingmental health and the adverse psychological consequences of living with this chronic disease (59).The most recent guidance from ADA and EASDrecognizes the increasing challenges facing PCPstrying to navigate these complexities in today’s rapidlyevolving climate (11–15). These guidelines offer a moreholistic approach to meeting the diverse needs of individuals with diabetes, informed by the latest evidenceon both pharmacological and nonpharmacologicalinterventions. The recommendations most relevant toprimary care are discussed below.UNDERLYING PRINCIPLES OF PERSONCENTERED DIABETES CAREDiabetes Management Decision CycleCentral to the ADA/EASD consensus guidelines isthe decision cycle for person-centered management(Figure 3). This model shifts from the traditionalmanagement goal of achieving glycemic control to thebroader goals of preventing complications and optimizing quality of life. Its aim is to put people with type2 diabetes at the center of their own care by promotingholistic assessment and shared decision-makingbetween clinicians and patients to arrive at mutuallyagreed upon management plans. A person-centeredapproach that acknowledges the competing demandsof multimorbidity and is respectful of and responsiveto individuals’ preferences and barriers, includinglimited access to and prohibitive costs of therapies, isessential to effective diabetes management. This modelis intended to build management around individualpatients, taking into consideration their personal preferences, clinical characteristics, and comorbidities, andto consider the benefits and risks of glucose-loweringmedications in this context. Shared decision-makingthat presents the risks and benefits of alternativetreatment options is a useful strategy to arrive at thebest treatment course for each person (13,14).Overall, the ethos of care moves away from anemphasis on general treatment targets to one onindividual goals based on the whole person. Central tothis process is the need for clinicians to be culturallysensitive and to consider factors such as patients’health beliefs, possible literacy deficits and cognitiveimpairments, and fears or concerns when consideringtreatment choices, given the impact of such factors ontreatment efficacy (13,14).Diabetes Self-Management Education and SupportThe latest guidelines specifically identify diabetesself-management education and support (DSMES)as a key intervention to enable individuals to makeinformed decisions and empower them to assumeresponsibility for the day-to-day management of theircondition. The ADA/EASD consensus committee’sevidence review highlighted DSMES as a cost-effectiveintervention with a robust evidence base demonstrating improvement in patient knowledge andclinical and psychological outcomes, as well as positiveimpacts on medication adherence, glycemic control,and all-cause mortality (60,61). Recommended corecomponents of DSMES have been described in detailelsewhere (62,63).Renewed Focus on Lifestyle InterventionsImportantly, the ADA/EASD consensus recommendations remind clinicians that lifestyle interventions,particularly those focusing on weight loss, obesitymanagement, and physical activity, remain pivotal totype 2 diabetes management (13,14). The consensuscommittee placed lifestyle interventions, includingconsideration of diet quality, energy restriction, andphysical activity, alongside glucose-lowering drugsas potential components of the diabetes management plan. Although no specific diet is preferred,dietary approaches including the Mediterranean,DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension),low-carbohydrate, and vegetarian eating patternsare highlighted. The guidance advocates increasingphysical activity through various strategies, includingcommon activities such as swimming and walking andless frequently practiced options such as yoga and taichi. The aim should be to support lifestyle changes thatare feasible and sustainable and to develop a regimentailored to the patient’s preferences. All overweightand obese people with diabetes should be advised ofthe health benefits of weight loss and encouraged toengage in programs of intensive lifestyle managementand, in particular, energy restriction, including mealreplacement programs.6 Person-Centered, Outcomes-Driven Treatment: A New Paradigm for Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care

NEW CONSIDERATIONS FORPHARMACOLOGICAL GLUCOSE-LOWERINGTHERAPYhypoglycemia and is an inexpensive option that isaccessible worldwide (64).The latest ADA/EASD consensus guidelines and ADAStandards of Care still recommend metformin asfirst-line therapy for most people with type 2 diabetes(11–15). This guidance largely relates to historicaldata from the UKPDS, although there is continueddiscussion regarding the possible cardiovascularbenefit of metformin (64). At present, metforminhas a well understood safety profile and a low risk ofDeciding What Comes After MetforminThe latest treatment guidelines provide an algorithmfor intensifying pharmacological therapy beyondmetformin that represents a true paradigm shift fromearlier recommendations. Now, rather than selectingdrugs mostly on the basis of their glucose-loweringefficacy, the new guidi

Associate Director, Family Medicine Residency Program. Abington Jefferson Health Abington, PA. Person-Centered, Outcomes-Driven Treatment: A New Paradigm for Type 2 Diabetes. in Primary Care. This publication has been supported by unrestricted educational grants to the American Diabetes Association from Eli Lilly and Company and Novo Nordisk. 2020