Transcription

NASCIO: Representing Chief Information Officers of the StatesNASCIO Staff Contact:Stephanie JamisonIssues Coordinatorsjamison@amrms.comThe MITA Touch: State CIOs andMedicaid IT TransformationConsuming nearly a third of state budgetsnationwide, Medicaid serves as thecountry’s largest insurance program. As ofFY 2007, over 55 million people wereMedicaid beneficiaries and approximately 355 billion dollars per year are spent byfederal and state governments to administer Medicaid services.1 With thesenumbers burgeoning every year, thenation’s top state officials have watchedfederal action regarding Medicaid with acareful eye. Governors have consistentlyplaced Medicaid issues among their toppriorities, along with other areas of healthcare, particularly since its costs began totake a significant toll on state budgets.Now, state CIOs across the country arerecognizing that Medicaid and Medicaidreform initiatives affect their offices andpolicies as well. Perhaps one of the largestfederally-initiated Medicaid reform effortsto affect the state CIO is the creation,development and emerging implementationThe MITA Touch: State CIOs and Medicaid IT Transformationof the Medicaid IT Architecture (MITA).Since Medicaid is a state-administeredprogram, every state manages Medicaiddifferently—the passage of the federalDeficit Reduction Act (DRA) in 2006 onlywidened disparities between the states.The enactment of the DRA brought,among other changes, more flexibility forstates to make certain determinationsregarding Medicaid eligibility and service,and its passage was pushed in part by theNational Governors Association.2However, the inconsistencies among stateMedicaid systems goes beyond the effectsof the DRA—there is no collective way toprocess Medicaid claims or exchange dataamong state agencies and their stakeholders, nor between state and federalagencies. These disparities led the federalDepartment of Health & Human Services’(HHS) Centers for Medicare and MedicaidServices (CMS) to formulate the MITA vision,which seeks to connect organizational silosNASCIO represents state chiefinformation officers and informationtechnology executives andmanagers from state governmentsacross the United States. For moreinformation visit www.nascio.org.Copyright 2008 NASCIOAll rights reserved201 East Main Street, Suite 1405Lexington, KY 40507Phone: (859) 514-9153Fax: (859) 514-9166Email: NASCIO@AMRms.com1

NASCIO: Representing Chief Information Officers of the Statesand align Medicaid with IT to focus onhealthcare outcomes and data uniformityacross the enterprise.3 In recent years, state CIOs across thecountry have begun to take an active rolein state health IT efforts as initiatives suchas electronic medical records, data exchangeand interoperability issues have madecollaboration with IT departments criticalfor success. Similar to the importance ofCIO involvement in these initiatives, participation in the MITA process is essential aswell. Implementation of MITA is certainto affect state CIOs, particularly asagency and department CIOs look to thestate CIO to provide an enterprise viewon linking disparate agency silos in orderto implement the MITA framework. The MITA Vision: A View FromThe TopMITA is a business-driven enterprisearchitecture the employs service-orientedarchitecture (SOA).4 Traditional MedicaidManagement Information Systems (MMIS)are costly, require users to navigatethrough multiple functional systems toperform a single task, and are historicallylargely “platform-dependent” and do notcommunicate easily across functional ortechnical boundaries—making information difficult to share or reuse functionality.5 These independent systems, coupledwith a lack of data standards, presentchallenges in garnering a holistic view ofthe services utilized by Medicaid beneficiaries and in sharing information acrosssystem platforms or inter/intra stateboundaries.6MITA is a national framework that providesa blueprint consisting of models,guidelines and principles to be used bystates as they implement enterprisesolutions.7 The MITA initiative envisionsmoving from traditional MMIS to webbased, patient-centric systems that areinteroperable within and across all levelsof government. The goals of MITA seek todo the following:2 Improve health care outcomesAlign with Federal Health ArchitectureEnsure patient-centric views notconstrained by organizational barriersMake use of common IT and datastandardsFoster interoperability between andwithin state Medicaid organizationsProvide web-based access andintegration while respecting patientprivacy and confidentiality concernsSupport software reusability withcommercial off-the-shelf (COTS)softwareIntegrate seamlessly clinical andpublic health data.8MITA is driven by three coreArchitectures—Business, Technical andInformation—coming together to form asystem that aligns with unique state ororganizational needs, but relies oncommon industry standards to make itwork. Each architecture hosts a WorkingGroup comprised of various stakeholders,from vendors and private organizations tostate participants; some Working Groupshave hundreds of members, with allcontributing and providing input onprocesses. These architectures intertwinewith one another and are inter-dependent for success—all are crucialcomponents to the “three-legged” stoolthat will hold up MITA.MITA’s Three ArchitecturesBusiness Architecture (BA): The BAdescribes the needs and goals of individual states, provides a collective vision ofthe future and is a conceptual constructthat comprises models, matrices andtemplates. 9 Considered to be the mostmature of the three architectures, the BAincludes the following components:Operations Concept, the MITAMaturity Model, the Business ProcessModel, the Business Capability Matrix, theMITA State Self-Assessment and MITABusiness Services. Using the BA, states canassess their current capabilities andformulate a vision for the future.The MITA Touch: State CIOs and Medicaid IT Transformation

NASCIO: Representing Chief Information Officers of the StatesTechnical Architecture (TA): The TAincludes the MITA ApplicationArchitecture, MITA Data Architecture,Technology Architecture, TechnicalCapability Matrix, and MITA standards. TheTA is meant to provide IT staff (either stateor vendor) with guidance and specifics onhow to implement MITA and must notonly support the MITA vision, but alsobusiness strategies and plans, and linktechnology choices to business needs.10Information Architecture (IA): Driven bythe Business Architecture’s BusinessProcess Model, the IA is a consolidation ofprinciples, models, and guidelines thatform a template for the States to use todevelop their own enterprise informationarchitecture.11 The IA deals with themanagement, organization and integration of data, and uses theHealth Level 7 (HL7) Reference InformationModel (RIM) as a basis for identifying thestandard data elements that are used bystates in the development of MITAbusiness services.12 The BA and the IAwork together to map enterprise data toprocesses and are meant to be differentviews of the integrated enterprisearchitecture.13 The methodologyemployed to define the MITA IA has beentailored from several industry-acceptedmodels including NASCIO’s EnterpriseArchitecture Toolkit.14MITA in the States:Opportunities and Challenges The Opportunities of MITA inMedicaid TransformationA Focus on the Outcomes: Consistentwith other health IT-related initiatives,MITA offers states much more than atechnical architecture or businessprocess—it also offers the potential toreduce costs and improve the quality ofcare. With approximately one out of everyfive health care dollars invested into theMedicaid program15, states are beginningto take a significant interest in the returnon investment of these dollars.Implementing MITA, and thereby movingThe MITA Touch: State CIOs and Medicaid IT Transformationtoward an eventual goal of an interoperable network that will communicate acrossorganizational boundaries, could helpidentify where duplicative dollars arebeing spent and how more targeted carefor the individual may be achieved. Thishorizontal use of data that MITA wouldenable could potentially lead to significantcost savings across the enterprise, inaddition to health benefits to the individual.A Focus on Health IT Initiatives: A significant driver for states to begin incorporating health IT aspects into Medicaid werethe Medicaid Transformation Grantshanded down from Congress in 2005.These grants were awarded to 33 states,and totaled 150 million to allow states towork on health IT and HIE initiatives.16These programs are beginning to sunsetand the grant fund money will soon rundry—currently, CMS is not opposed toadministrating another round of grants tosustain these programs, but it will dependon future Congressional action andfunding.Texas Uses MedicaidTransformation Grant Money forFoster ChildrenIn April of 2008, the state of Texas unveiledthe Texas’ Health Passport program forits approximately 27,000 children in fostercare. This program keeps track of a child’sdiagnoses, treatments and prescriptionswith data collected mostly fromMedicaid.17 This program allows childrenin the foster care program to avoidduplicative tests and treatments, and alsoallows foster parents know of any medicalconditions at the outset so that thechildren may receive the best and mostrelevant care possible.Implementing MITA,and thereby movingtoward an eventualgoal of an interoperable network that willcommunicate acrossorganizationalboundaries, couldhelp identify whereduplicative dollarsare being spent andhow more targetedcare for the individual may be achieved.The Health Passport program reducesMedicaid costs by eliminating unnecessarycare and was funded by a 4 millionMedicaid Transformation Grant from CMS.CMS estimates that the average monthlyMedicaid cost for a foster child is five timeshigher than for a non-foster child. Forbehavioral services, the cost for foster3

NASCIO: Representing Chief Information Officers of the Stateschildren soars to 40 times that of nonfoster children.18 Texas has developed thisweb-based application, accessible only bydoctors and foster parents, and is currentlythe only program of this nature in thecountry. Texas’ enterprise datawarehouse was designed to be MITAconsistent using their MedicaidTransformation Grant money to linkseveral organizational silos together.funding for this program. Additionally, theSouth Carolina Hospital Association, theSouth Carolina Primary Care Association,the Office of Rural Health and other healthcare provider groups have signed ontoSCIEx. While it is too early to tell the ROIon this program, this program in SouthCarolina indicates a fundamental shifttoward sweeping Medicaid reform effortsin the states that incorporate health ITinitiatives.In lieu of universal federal standards, thestates have played a large role in steeringhealth IT and health information exchangeefforts. Many states have well-developedregional health information organizations,and others have statewide health information exchange systems already in place.These existing initiatives largely focus onpublic-partnerships between state andprivate hospitals with physician offices andnot on public health specifically. However,shrinking state budgets, rising Medicaidcosts and the cost-saving nature of theseinnovative practices have caused a naturalturn inward as states begin to think aboutintegrating these revolutionary HealthInformation Technology and HealthInformation Exchange (HIT/HIE) initiativessuch as e-prescribing and electronichealth records into their Medicaidprogram.For more information on SCIEx, or otherSouth Carolina’s Medicaid reform efforts,please visit www.dhhs.state.sc.us/dhhsnew/index.asp.South Carolina Medicaid RecordsGo Online4A Focus on Interoperability: The MITAframework is intended to foster integratedbusiness and IT transformation across theMedicaid enterprise to improve administration.20 MITA focuses on connecting thesilos that exist between state agencies,and between state and federal agencies, inorder to create information-sharing on ascale that has never been done before.Medicaid beneficiaries commonly receivepublic services other than Medicaid. Byallowing these agencies that may servicethe same beneficiaries to communicatewith one another could provide amultitude of benefits for both citizen andgovernment. The Challenges of MITASouth Carolina’s 700,000 Medicaidbeneficiaries saw their medical records goonline in July of 2008. This program,dubbed the South Carolina HealthInformation Exchange, or SCIEx, was builtby the state Budget and Control Board’sOffice of Research and Statistics. TheSCIEx links hospitals, doctors, clinics andother health-care providers with themedical records and the state is hoping fora reduction in paper, printing and storagecosts by eliminating paper records.19Organizational Resistance WhenConnecting Silos: In any sweeping reformeffort that encompasses governmentagencies at all levels, and particularlythose reforms that require agencies toshare data and collaborate at an unprecedented magnitude, connecting organizational silos is significantly easier said thandone. Cross-boundary collaboration is apopular buzzword in IT and its successesare widely hailed as significantaccomplishments because it can be verydifficult to achieve.The South Carolina Department of Healthand Human Services administers theMedicaid program and provided theThe amount of collaboration required forMITA to become fully operational isThe MITA Touch: State CIOs and Medicaid IT Transformation

NASCIO: Representing Chief Information Officers of the Statesmonumental and may be met with considerable resistance at the outset.Organizations that previously managedthese programs in their individual silo mayfeel territorial toward the developmentand administration of new initiatives, ormay be resistant to change altogether.People, not technology, often serve as thebiggest hurdle to overcome in MITAimplementation.Blending Technology and BusinessProcesses: MITA is, at its core, a businessprocess and not a specific technologysolution. It is meant to be a framework, atool-kit and a roadmap for states tofollow—each state builds its own ITsolution based on standards, models andprocesses contained within the MITAframework.21 However, it is obviously aprocess that will require a significantoverhaul of a major IT legacy system. Dueto the absolute blend between the technical and business aspects, MITAimplementation becomes an inherentlycomplicated challenge. State CIOs mustunderstand that this can be a dauntingtask and will require considerable collaboration between state agencies andvendors, and a substantial modernizationof current IT systems and also businesspractices and processes.Technical challenges arise regarding SOAand the knowledge gaps that may existwithin agencies in regards to building orpurchasing SOAs. MITA employs SOA,however, neither the technology nor thegovernance to tie different SOAs togetherare fully developed yet, making the maturityof SOA a significant challenge. Anothertechnical challenge is that since states are indifferent stages with their current Medicaidsystems, some may be ready to replace witha fully SOA-enabled system while others arenot. Therefore, part of the SOA challenge ishow to SOA-enable legacy systems untilthey can be “ripped and replaced” with afully SOA-enabled system. State CIOs mustthink about how to engage old mainframelegacy or client-service systems, so that ineven if a SOA-enabled system is notimplemented immediately, the long-termbenefits remain.The MITA Touch: State CIOs and Medicaid IT TransformationAdapting COTS packages to current andevolving business processes entailsconsiderable challenges. One of thechallenges with a COTS package is thenecessity to adopt the underlyingbusiness rules that have beenprogrammed into a purchased package.Unless the application has been built toafford the ability populate the systembusiness rules defined by the enterprisethrough a table driven approach, theenterprise will have to adapt to the systemby adopting the foundational businessrules upon which the system was built.The Long and Winding Road: MITAimplementation is not a process that willgo rapidly—nor is it intended to do so.CMS has been working on MITA forapproximately five years, and estimatesthat it will take five to ten more years toarrive at a fully implemented and interoperable system. This is an initiative thatwill outlast political administrations andwill require dedication and funding for asubstantial period of time. Incrementalprogress is the name of the game andacknowledging and anticipating that MITAwill require a “slow and steady” approachand planning its progress as such mayhelp decrease “are we there yet?” frustrations that may arise.Find Me the Money: FundingMITAMITA is, at its core, abusiness process andnot a specifictechnology solution.It is meant to be aframework, a tool-kitand a roadmap forstates to follow—each state builds itsown IT solutionbased on standards,models andprocesses containedwithin the MITAframework.States have significant concerns regardingfunding MITA—particularly in light ofrecent state budget worries across thecountry. With states responsible for theinitial outlay of money, in times of fiscalstress, states may grapple with how toprovide adequate funding up front inorder to receive matching rates. There areseveral scenarios in which CMS envisionsits role in funding MITA implementation—the sums of funding vary between modelsand depend on the type and the extent ofcollaboration between Medicaid agenciesand non-Medicaid agencies.5

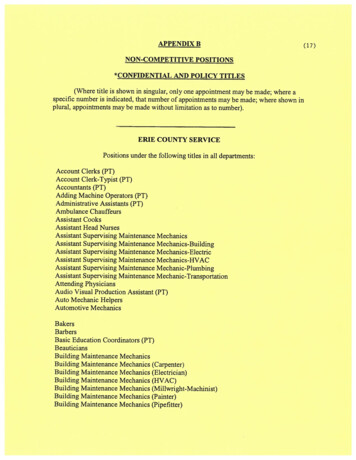

NASCIO: Representing Chief Information Officers of the StatesMATURITY LEVELSBUSINESS AREABUSINESS PROCESS1Member ManagementEnroll MemberProvider ManagementEnroll ProviderContractorManagementManage ContractInformationOperationsManagementEdit/Claim EncounterProgram ManagementMaintain Benefit/ReferenceInfoCare ManagementEstablish CaseProgram IntegrityIdentify CaseRelationshipManagementManage BusinessRelationship2345State Self-AssessmentThe State Self-Assessment: In 2007, CMSintroduced its State Self-Assessment (SS-A)to serve as a key component in obtainingFederal Financial Participation (FFP) dollarsto update or replace existing MMISsystems—all states are supposed tocomplete the SS-A in order to establish abaseline on the current state of their MMISsystems. This will serve as the basis onwhich the match rates will be set. The SSA captures a snapshot of the state’scurrent “as is” and future “to be” progressin regards to the MITA maturity levels.The maturity models range from Level 1 inwhich the agency performs the basicfunctions of enrollment and claimsprocessing to Level 5 which is an interoperable national system of the Medicaidenterprise—Level 5 is several years awayfrom actual attainment. Future enhancements to MMIS systems must be tied tothe functionality of the system, relative tothe maturity model, in order to achieveenhanced funding—the APD must clearlydemonstrate that funds will lead toadvancement in the MITA maturity modelin order to get approval from CMS. Formore details on the MITA Maturity Model,please see Appendix II.6The States and the SS-AMassachusetts: In early 2008, theCommonwealth of Massachusetts’Executive Office of Health and HumanServices (EOHHS) began addressing theSS-A in three components, each fundedthrough separate APD’s at the 90% FFPlevel. Component One is the “as-is” statusof MassHealth’s (the MassachusettsMedicaid program) business; ComponentTwo is the “as-is” and the “to-be” assessment of the Department’s of Public Health,Mental Health and Mental Retardation;Component Three is the “to-be” status ofMassHealth following implementation ofthe NewMMIS.One of the benefits that EOHHS hopes toachieve from Component One is the totalinventorying and indexing of theoperations documentation that supportsMassHealth into the MITA software Toolkit.The Toolkit and eventual documentrepository will be supplemented from theComponent Two MITA Project documents,and will also be updated duringComponent Three for MassHealth ”to-be”future requirements planning [postNewMMIS], and will be maintained indefinitely by the EOHHS Office of Compliance.The MITA Touch: State CIOs and Medicaid IT Transformation

NASCIO: Representing Chief Information Officers of the StatesComing out of the MITA study should bethe basic understanding of what is neededfor an EOHHS-wide common case recordfor each member/recipient/client, theneed for a common client index, and theplan for information exchange betweenusers. Identifying common businessfunctions, and providing common systemssolutions, will assist in implementing theSOA/open solutions/shared resources thatconstitutes the target IT architecturalvision for the Commonwealth.Massachusetts anticipates the SS-Aprocess to be complete by early 2011.Advanced Planning Document (APD)Process: The SS-A is meant to be submitted with an APD to CMS’ regional offices,and is prepared by the agency that housesMedicaid—state CIO offices do notgenerally have responsibility for itspreparation, although this may change asMITA continues to evolve. While state CIOsmay not typically have a hand directly inthe funding aspect of Medicaid and MITAimplementation, they need to ensure that,in the APD process, that the requests madeby the Medicaid agency are in line withthe state enterprise architecture. Also,state CIOs or their staff may be called uponto help prepare or contribute tocomponents of the SS-A or the APD.For the most part, states are just beginningto embark on the MITA journey. However,there are numerous ways that the journeywill lead to a better destination inMedicaid delivery and beyond. For stateCIOs, the MITA implementation investmentwill have returns in its reusablecomponents across the enterprise. MITA asa business function will reach acrossMedicaid programs nationwide and beyondinto multiple program areas, such asbehavioral health, and can drive processstandardization across the enterprise. Forexample, provider registration, clientindexes and common intake are reusablecomponents that can be leveraged by otherprograms. While there will always be corefeatures to a Medicaid system, many of thefeatures of those systems can be applied atan enterprise level across various silos.The MITA Touch: State CIOs and Medicaid IT TransformationCall to Action: What State CIOsCan Do TodayWhile Medicaid reform is far from anemerging trend, state CIO involvement inhealthcare at any level is a relatively recentphenomenon. It was not long ago when astate CIO would have never imagined thattheir position would play a key role inhealthcare delivery or reform. Whileserving as a chief administrator of MITAis not always feasible for a state CIO, it isimperative that they be involved in theseefforts as their state works to developand implement this business processwhich will lead to a sweeping technicaloverhaul. MITA has been in existence foronly five years, and states are, for the mostpart, just beginning to plan for itsimplementation. By making a choice to beinvolved in MITA at the beginning phase,state CIOs will be in a better position tohelp make decisions and shape policiesthat will likely affect them eventually.22 Get Informed: Become fully informedon the MITA plan in your state andexplore its implication on your state—this must be done before anythingelse. Reach out to your state’sMedicaid agency, or the departmentthat is responsible for administeringthe current MMIS system, and find outwhere they are in MITA developmentand implementation. For a list of MITAState Contacts, please see Appendix I. Collaborate, Educate, and Facilitate:Due to their enterprise view, state CIOscan serve as a convener amongdisparate state agency CIOs, and canwork to foster relationships betweenthe agencies that could potentiallybenefit from an interoperable MITAsystem. Helping to drive thesedisparate agencies toward collaboration, and serving as an educator forthose agency CIOs or other officialsabout the MITA initiative, can increasea collaborative spirit once theenterprise-wide benefits are realized.Working to help facilitate this processis something that the state CIO isWhile state CIOsmay not typicallyhave a hand directlyin the funding aspectof Medicaid andMITA implementation, they need toensure that, in theAPD process, that therequests made by theMedicaid agency arein line with the stateenterprise architecture.7

NASCIO: Representing Chief Information Officers of the Statesuniquely poised to do. State CIOs canalso act as a broker between statesand the vendor community.State CIOs must lookat their currentsecurity architectureand determine howto ensure implementation of MITA willcomply with thatarchitecture. Get Engaged: The MITA State SelfAssessment is a good starting pointfrom which to assess where your stateis currently at in terms of implementing a MITA system and next steps forfuture transformation to higher levelof maturity. While 2/3 of states are inthe process of planning for orcompleting this assessment, this alsomeans that 1/3 of states are not. Findout if your state is moving forward onbeginning the self-assessment or howfar your state may be down the trackson this project. Gauging the status ofthis will help determine the overallstatus on Medicaid modernizationefforts in your state. Align Enterprise Architecture: It isimperative that state CIOs rationalizethe MITA architecture against their stateenterprise architecture. Carefulconsideration must be given to allthree architectural layers – business,information and technical architectures.Policies and standards outlined withinthe state enterprise architecture willcontribute toward proper governancefor state implementations of MITAwithin the state enterprise. Thisgovernance will include architecturalprinciples for conceptual and logicalmodeling, information exchange,records management and preservation,security, disaster recovery, and SOA.Security architecture will demand specialemphasis. State CIOs must look at theircurrent security architecture anddetermine how to ensure implementationof MITA will comply with that architecture.In this respect, state CIO involvement inthe technical and information architecture components of MITA (of the threeArchitectures outlined above), becomesmore significant. State CIOs, whenworking to connect agency silos andgauging the status of those systems, canbegin to determine if the systems areconducive to eventual collaboration onthe large scale that MITA would require.8 Look Outside At The Customer: Animportant component of MITA is theimpact on the citizen user, and stateofficials must ask themselves whatMITA adoption will mean to them.Making sure that the infrastructure isavailable, scalable and secure is acritical aspect of state CIO involvement in MITA development.Ultimately, state governmentimplementation of MITA implementation must be centered on benefitingthe citizen. The widespread collaboration that is MITA’s goal will lead tomany of the same goals of otherhealth IT initiatives—performancemanagement and accountability,coordination with public health andhealth outcomes, providing anenvironment that is adaptable andresponsive to changing business andtechnology drivers, elimination ofmedical error, increasing informationquality and availability to improvedecision making in health caremanagement and program administration, reduction of duplicative carethereby reducing costs, and a morecomplete medical history in order tohelp physicians make the mostinformed decisions possible.Ultimately, MITA encompasses andemphasizes many of the same goals thatstate IT works to carry out every day—tocollaborate across agencies, connectdisparate silos and improve citizen serviceas a result of these efforts. State CIOsunderstand these common threads thatconnect public agencies across the stateand their unique enterprise view lendsitself to involvement in MITA. As key publicofficials, state CIOs must be aware ofemerging trends that will affect their states,as well as those trends that will affect theiroffices directly. By recognizing what thegoals of the MITA initiative are, and byensuring that state enterprise architecturesystems and standards are in line withthese goals, state CIOs can help bridge thegap between agencies and work to makeMedicaid reform through MITA implementation a reality in their state.The MITA Touch: State CIOs and Medicaid IT Transformation

NASCIO: Representing Chief Information Officers of the StatesAppendix I: MITA State & Federal ContactsCMS Regional Office ICTMark Heuschkel mark.heuschkel@ct.govMETony Marple tony.marple@maine.govMAStephen Buchner stephen.buchner@state.ma.usNHDiane Delisle ddelisle@dhhs.state.nh.usRIFrank Spinelli fspinell@dhs.ri.govVTJudy Higgins judyh@ahs.state.vt.usCMS Regional Office IINJMichele Romeo Michele.Romeo@dhs.state.nj.usNYMario Tedesco mxt07@health.state.ny.usCMS Regional Office IIIDCRoderic Allsopp roderic.allsopp@dc.govDEDave Mayer dave.mayer@state.de.usMDRenee Hartsock rhartsoc@dhmh.state.md.usPASandy Patterson SAPatterson@state.pa.usVASylvia Hart sylvia.hart@dmas.virginia.govWVPat Miller patmiller@wvdhhr.orgCMS Regional Office IVALPaul Brannan paul.brannan@medicaid.alabama.govFLAlan Strowd strowda@ahca.myflorida.comGASonny Munter smunter@dch.ga.govKYJohn Hoffmann john.hoffmann@ky.govMSTeresa Karnes pptlk@medicaid.state.ms.usNCMamta Gentry mamta.gentry@ncmail.netSCRhonda Morrison morrison@scdhhs.govTNBrent Antony brent.antony@state.tn.usCMS Regional Office VILAnita Corey anita.corey@illinois.govINRandy Miller randy.miller@fssa.in.govMIJay Slaughter slaughterj@michigan.govMNKristi Grunewald kristi.grunewald@state.mn.usOHJohn Wanchick wanchj@odjfs.state.oh.usWIKen Dybevik dybevkk@dhfs.state.wi.usThe MITA Touch: State CIOs and Medicaid IT TransformationCMS Regional Office VIARMarilyn Strickland marilyn.strickland@arkansas.govLACurtis Boyd curtis.boyd@

dubbed the South Carolina Health Information Exchange, or SCIEx, was built by the state Budget and Control Board's Office of Research and Statistics. The SCIEx links hospitals, doctors, clinics and other health-care providers with the medical records and the state is hoping for a reduction in paper, printing and storage costs by eliminating .