Transcription

3.0 ANCCContact HoursDiane Angelini, EdD, CNM, NEA-BC, FACNM, FAAN andElisabeth Howard, PhD, CNM, FACNMObstetricTRIAGE:A Systematic Review ofthe Past Fifteen Years:1998-2013AbstractBackground: Triage concepts have shifted the focus of obstetric care toinclude obstetric triage units. The purpose of this systematic review is toexamine the literature on use of triage concepts in obstetrics during a15-year time frame.Methods: A systematic review was completed of the obstetric triageliterature from 1998 to 2013 using the electronic online databases fromPubMed, CINHAL, Ovid, and Cochrane Library Reviews within the Englishlanguage. Reference lists of articles were reviewed to identify other pertinent publications. Both peer-reviewed and non–peer-reviewed documentswere used. Inclusion criteria: articles specifically related to obstetric triageor obstetric emergency practices in the hospital setting. Exclusion criteriaincluded: manuscripts that focused on general, nonobstetric emergencyand triage units, telephone triage, out-of-hospital practices, other clinicalconditions, and references outside the time frame of 1998–2013.Results: Key categories were identified: legal issues and impact ofEmergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA); liabilitypitfalls; risk stratification (acuity tools); clinical decision aids; utilization, patientflow, and patient satisfaction; impact on interprofessional education andadvanced nursing practice; and management of selected clinical conditions.Components of a best practice model for obstetric triage are introduced.Conclusion: Seven key triage categories from the literature were identifiedand best practices were developed for obstetric triage units from thissystematic review. Both can be used to guide future practice and researchwithin obstetric triage.Key words: Interprofessional education; Obstetric emergency services;Obstetrics, Triage.284volume 39 number 5September/October 2014Copyright 2014 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

bstetric triage has now become part ofthe fabric of obstetrics. As a specialtywithin perinatal care, it came of age inthe 1980s–1990s in the United States andinternationally, and flourished during theearly part of the 21st century. The past15 years have demonstrated significant changes in how triage concepts have been applied to obstetric care. We undertook this review because development of new triage facilitiesand role changes among providers in the obstetric triage setting have now altered how obstetric care is both assessed andprovided. We felt the timing was right to review the changesin obstetric triage care as a composite. The purpose of thissystematic review of the obstetric triage literature from 1998to 2013 is to delineate key categories of content, which haveinfluenced obstetric triage during this time frame.utilization of obstetric bed capacity, provide less turnoverof patients in the labor/delivery setting, allow for moreimmediate rapid response to obstetric emergencies,prevent unnecessary labor admissions, decrease waitingtimes, and provide heightened assessment of fetal andmaternal well-being (Angelini, 2013).Location of obstetric triage units varies across institutions. Most units are within close proximity to labor anddelivery, yet there is discrepancy as to where such unitsare best located, whether close to or remote from thelabor unit (Angelini, 1999a; Angelini & LaFontaine,2013). In some settings, obstetric triage services maycome under the role of the laborist, hospitalist, or midwife. A recent draft of core competencies for the Societyof OB/GYN Hospitalists, part of the American College ofObstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG), lists obstetric triageBackgroundservices coming under the role of hospitalist/laborist(Jancin, 2011).Pregnant women presenting to an emergency roomsetting are often at a gestational age less than viability(23–24 weeks). Many of these women are evaluated ina general emergency department. However, mostwomen with pregnancy complaints at 20–24 weeks gestation or greater are evaluated in an obstetric triageunit (Angelini, 1999a). In larger birthing facilities, aseparate obstetric triage unit often exists to evaluate allobstetric complaints regardless of gestational age; insmaller birth settings, labor and delivery may be theappropriate area to assume obstetric triage functions,specifically labor assessment (Angelini, 1999a; Angelini,2013).Blend Images / AlamyOIn the United States, obstetric triage has emerged to servemultiple functions within obstetric care. A major factor inthe development of obstetric triage was the introduction ofthe Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act(EMTALA), which took effect in 1986 (The ConsolidatedOmnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985) and instituted practice mandates in the emergency setting. Obstetrictriage is primarily a screening platform for labor evaluation. However, in many settings, it is used to manage early,mid, and late pregnancy complications as well as emergentobstetric conditions. Obstetric triage units are often the“gatekeeper” for initial assessment of obstetric complaints.Factors responsible for this movement toward useof obstetric triage units include: the need to improveSeptember/October 2014MCNCopyright 2014 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.285

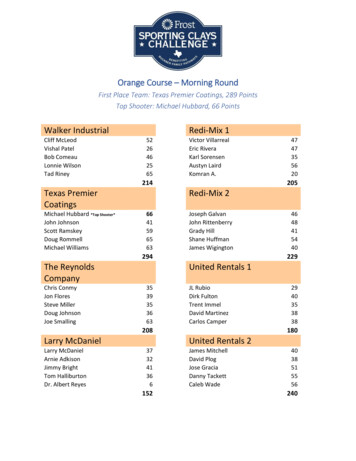

Access to multiple clinical services makes obstetrictriage a highly functional and desirable adjunct to overallobstetric services. Use of direct imaging, laboratoryservices, fetal evaluation (both fetal monitoring andultrasound usage), availability of consultants, and immediate care by an obstetric provider make obstetric triageunits valuable in providing high reliability perinatal care(Angelini, 2013; Angelini & LaFontaine, 2013).Beyond regulations from the federal government,professional associations offer recommendations for obstetric triage care. The Association of Women’s HealthObstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) recommendsthat for the initial triage process (10–20 minutes), 1 nurseto 1 patient should be the staffing ratio; however, this maychange to 1 nurse to 2–3 pregnant women as maternalfetal status is assessed and conditions determined(AWHONN, 2010). It is further recommended that fetalassessment and status be included in that initial triage assessment before the level of care is determined. This is inkeeping with ACOG and American Academy of Pediatrics(AAP) Guidelines for Perinatal Care that any woman whopresents to the labor and delivery area should be evaluatedin a timely manner. Minimally, this includes maternal vitalsigns, frequency and duration of contractions, and documentation of fetal well-being (AAP & ACOG, 2012). Ifthe woman is suspected of being in labor or has rupturedmembranes or vaginal bleeding, further assessment isrequired promptly (AAP & ACOG, 2012). The Guidelines for Perinatal Care (AAP & ACOG, 2012) outline thecomponents of a comprehensive evaluation based onmaternal–fetal status, when the responsible healthcareprovider should be notified, and what should bedocumented in the medical record.286volume 39 number 5Women with nonemergent medical conditions can alsopresent to obstetric triage or to an emergency departmentsetting when their normal source of medical care is inaccessible or unavailable. In a 2008 study of 287 womenpresenting to an ob/gyn emergency room/triage unit withnonemergent medical complaints, 36% came for carebecause they believed they had a true emergency, 42%presented secondary to physician referral, and 21% camesecondary to access barriers (e.g., lack of primary provider)(Matteson, Weitzen, LaFontaine, & Phipps, 2008). Seventypercent reported a reason for the visit that was unrelated toeither obstetrics or gynecology (Matteson et al., 2008).Obstetric triage has clearly become one of the mostcritical perinatal service innovations to emerge in the last15 years (Angelini & LaFontaine, 2013). Additionally,EMTALA has helped to reshape the care provided to activelabor patients who are evaluated in the obstetric triage setting (Angelini, 2006; Angelini & Mahlmeister, 2005;Caliendo, Millbauer, Moore, & Kitchen, 2004; Glass,Rebstock, & Handberg, 2004; Kriebs, 2013; Mahlmeister& VanMullem, 2000) and to some extent parallels thedevelopment of obstetric triage. Over the decades, roleresponsibilities within the obstetric triage setting havechanged as nurses, physicians, midwives, and other providers have become part of a more collaborative model ofobstetric triage care (Angelini, 2006; Angelini, Stevens,MacDonald, Wiener, & Wieczorek, 2009).MethodologyA review was systematically conducted using the following electronic databases: PubMed, CINHAL, Ovid, andCochrane Library Reviews with search limits set tolocate studies related to obstetric triage published in thelast 15 years, from 1998 to2013 in the English language.Obstetric triage is defined as aspecialty area/unit within obstetrics with multifunctionalaspects (Angelini & LaFontaine, 2013). Two investigators screened titles and abstracts in both peer-reviewedand non–peer-reviewed publications, including commentaries and one book. Referencelists of each article werescanned to locate any additional or supplemental sources. The search was modifiedusing the inclusion terms: obstetric triage, obstetric emergency room, obstetric services,and obstetric emergency care.Other specific words used asinclusioncriteriawere:midwifery, advanced practicerole, and interprofessional/interdisciplinaryeducationwithin the 15-year time frame.September/October 2014Copyright 2014 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Figure 1Flow Diagram of Study Selection.Literature Search of Databases Ovid Cochrane Registry Cumulative Index to Nursing AlliedHealth Literature (CINAHL) PubMedReference List of articles retrieved were reviewedto identify additional pertinent articlesLimits: English languageYears: 1998 – 2013Search resulted Combined: 42Full Text of Articles Include: n 33Evaluative Research Policy Analysis Systems Analysis Legal Claims AnalysisReviews Descriptive Literature Review Clinical Review EditorialProspective Studies Intervention Survey Observational Scale Development Quality ImprovementSource: AuthorsSeptember/October 2014n 3n 1n 1n 5n 4n 8n 1n 1n 2n 2n 1n 4Journal articles were retrieved primarily from nursing,advanced nursing practice journals, and medical journals. Exclusion criteria were: general articles pertainingto emergency departments that do not have an integratedobstetric triage component, articles outside the 15-yeartime frame, telephone triage, out-of-hospital practices,and other more specific clinical conditions presenting toobstetric triage.A total of 33 appropriate publication sources, that metinclusion criteria, were reviewed (Figure 1). One of thesources was an editorial, and one was a book. Threeof the articles were obtained perusing additional reference lists.Articles were read in full by two independent reviewers to evaluate content relevance and to identify emerging themes covering the time period of 1998–2013. Ofthese 33 articles, 5 were comprised of evaluativeresearch methods; 17 were descriptive, clinical, or literature reviews, 10 were prospective studies; and 1 wasan editorial. The reviewers determined inclusion andexclusion criteria by appropriate content specific to obstetric triage. Seven topical categories, as listed in Table 1,were developed from the review and include the following: legal issues and impact9 records excludedof EMTALA; liability pitfalls;riskstratification(including acuity tools); clinical decision aids; utilization,patient flow, and patient Not specific to OB triagesatisfaction; the impact of Phone triageobstetric triage on interpro Generic, not R/T OB triagefessional education and advanced nursing practice; andselected clinical conditions inthe triage setting.Categories Within the ObstetricTriage LiteratureLegal Issues and Impact of EMTALAWith passage of EMTALA, as well as national standardsand guidelines for obstetric triage care, legal considerations have grown for obstetric triage providers.EMTALA encompasses a large segment of the scannedliterature during this time period. EMTALA holdshospitals and providers accountable for prompt screening and care for pregnant women who present to obstetric triage in active labor (Glass et al., 2004; Kriebs,2013). It prevents discrimination based on financialstatus and affects all hospitals that accept Medicarereimbursement.Key information regarding EMTALA that affects triage includes the following content. EMTALA mandatesthat the obstetric triage provider perform a medicalscreening examination (MSE). This provider is called aqualified medical person (QMP). This person does notneed to be a physician. This could be a certified nursemidwife (CNM), or other qualified person such as a laborMCNCopyright 2014 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.287

Table 1. Characteristics of Triage Studies (1998–2013)ArticleSettingPurposeMethodologyKey Findings/HighlightsCATEGORY 1 LEGAL ISSUES AND EMTALAAngelini, D. J. &Mahlmeister, L. R.(2005)U.S.Reviews liability in the triagesetting from the perspective ofEMTALA regulations and commonly seen obstetric complications inthe triage setting.Policy AnalysisPresents challenges with EMTALAlaw and describes strategies tomodify risks in the obstetric triagesetting.Bitterman, R. A.(2004)U.S.Purpose of supplement is to explain Policy Analysisthe changes made to the EMTALAregulations in 2003 and howpractitioners are affected by suchchanges.Detailed background and informationon specifics within EMTALA law.Kriebs, J. M.(2013)U.S.Provides overview of legal actsaffecting obstetric triage: EMTALAand HIPAA.Policy AnalysisCovers the MSE, requirements fortransport, labor and birth, recordkeeping and follow-up in EMTALAand disclosure of health information electronic media, HIPPA,and care of the adolescent underHIPPA.Glass, L.,Rebstock, J.,& Handberg E.(2004)U.S.Provides a basic overview ofEMTALA and specific strategiesfor risk reduction.LiteratureReviewDetails principal mandates,enforcement and violations,clinical situations that violateEMTALA with selected cases,and case analysis with risk reductionstrategies.Caliendo, C.,Millbauer, L.,Moore, R., &Kitchen, E. (2004)U.S.Provides basic review of EMTALAas pertains to obstetric triage andexperience of one birth center.Clinical ReviewA case presentation used. Keycomponents so as to not violateEMTALA; use of EMTALA friendlyinitiatives.CATEGORY 2 LIABILITY PITFALLSSimpson, K.R. &Knox, G. E. (2003)U.S.Provides a framework for reviewing Review ofprotocols and developing up-toLiabilitydate policies that decrease riskClaims Analysisexposure; common foci of perinatalliability claims.Provides common foci of liabilityclaims in obstetrics.Angelini, D. J.(2013)U.S.Provides overview of obstetrictriage liability pitfalls.Clinical ReviewProvides functions of obstetric triageunits and categories of risk in OBtriage.Angelini, D. J.(2006)U.S.To review the state of practice inthe obstetric triage setting.EditorialFuture key areas in triage: abdominal assessment in pregnancy,increased liability in obstetric triage,effects of EMTALA, and the future ofobstetric triage.Ventolini, G. &Neiger, R. (2003)U.S.Provides scenarios on areas ofincreased risk in OB triage.LiteratureReviewDiscusses maternal symptoms thatrequire special evaluation in abdominal pain, trauma, vaginal bleeding,vaginal fluid leakage, motor vehicleaccidents, and decreased fetalmovements noting areas for potential error and appropriate strategiesto be used.Mahlmeister, L. &Van Mullem, C.(2000)U.S.Presents the overall triage processClinical and Caseand nursing competencies; obstetric Law Reviewtriage in ambulatory and emergency Legal Reviewdepartment (ED) settings.Identification of triage pitfalls inambulatory, ED, and mother infantunits; reviews nursing competenciesand role of charge nurse.(continue.)288volume 39 number 5September/October 2014Copyright 2014 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Table 1. Characteristics of Triage Studies (1998–2013) (Continued.)ArticleSettingPurposeMethodologyKey Findings/HighlightsCATEGORY 3 RISK STRATIFICATION (Including Acuity Tools)McCarthy, M.,McDonald, S., &Pollock, W. (2013)Australia To evaluate the standard ofdocumentation for triage assessment of women presenting toED with preeclampsia orantepartum hemorrhage and todetermine whether the introduction of algorithms with decisionaids and an education programimproved assessment anddocumentation.ObservationalStudyIntroduction of the triage decisionaid section of the algorithm andeducation improved quality ofdocumentation and assessment.Paisley, K. S.,Wallace, R., &DuRant, P. G.(2012)U.S.A process improvement intervenQualitytion is described within a multicam- Improvementpus hospital system, producing an Projectobstetric triage acuity tool.Assigning acuity to patients in theform of an obstetric triage acuitytool improved the processes for alldata points; however, still notoptimal.Smithson, D. S.,Twohey, R., Rice,T.,Watts, N., Fernandes, C. M., &Gratton, R. J. (2013)CanadaPresents a 5-category obstetrictriage acuity scale (OTAS)developed with a comprehensiveset of obstetrical determinants.ScaleDevelopmentBy standardizing assessment, theOTAS improves performance andflowCATEGORY 4 CLINICAL DECISION AIDSLyons, A. (2010)UnitedTo describe the educational needsKingdom of ED staff regarding obstetricemergencies.QualityImprovementThe development of guidelines tomanage pregnancies and births inEDs requires the involvement ofmultidisciplinary care teams. Toimbed guidelines into practice,emergency drills should be initiatedfor staff.Angelini, D. J. &LaFontaine, D.(2013)U.S.Clinical ReviewExpert clinical guidance on morethan 30 clinical situations requiringobstetric triage or emergency care.Narrative of evidence-basedprotocols and guidelines for use inobstetric triage and emergencysettings.CATEGORY 5 UTILIZATION, PATIENT FLOW, AND PATIENT SATISFACTIONMolloy, C. &Mitchell, T. (2010)UnitedObtain views of women using OBKingdom triage and identify areas of bestpractices and areas in need ofimprovement.SurveyMost women were satisfied withwaiting times and time with provider;issues within environment of triagewere identified.Matteson, K. A.,Weitzen, S. H.,LaFontaine, D., &Phipps, M. G.(2008)U.S.Study designed to examine factorsassociated with women seekingtreatment for medically nonemergent conditions in a primarilyobstetric and gynecologic emergency facility.ProspectiveObservationalStudyOf the 287 women presenting withnonemergent issues: 36% of womenbelieved they had a true emergency,42% were physician referral, and21% because of access barriers.Common reasons and symptomsrevealed.Paul, J., Jordan,R., Duty, S., &Engstrom, J. L.(2013)U.S.Quality improvement projectProspectiveinitiated at a tertiary care center toInterventiondetermine whether LOS and patient Studysatisfaction in an obstetric triageunit could be improved by usingCNMs to manage and organize careon the unit.Patient satisfaction was measured. TheCNM-managed care group reportedincreased patient satisfaction with careincluding wait time, time spent withprovider, LOS, and overall carereceived. LOS shorter in CNM group(94 minutes vs. 122 minutes)(continue.)September/October 2014MCNCopyright 2014 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.289

Table 1. Characteristics of Triage Studies (1998–2013) sAnalysisKey Findings/HighlightsZocco, J., Williams, U.S.M. J., Longobucco,D. B., & Bernstein,B. (2007)Examination of variables involvedin obstetric triage with goal ofcreating more efficient system.Loper, D. & Hom,E. (2000)U.S.Quality improvement project aimed Qualityat providing seamless, single siteImprovement/care for pregnant patients.EvaluationResearchEffective patient classification systemscan help determine staffing needs,improve patient flow, and define staffmember roles and responsibilities.Preliminary analysis of the patientclassification system supports itsvalidity as a useful tool for determiningstaffing needs.Thrall, T. H. (2007)U.S.Description of how development ofan obstetric triage unit solves apatient flow issue.Development of an obstetric triageunit had a large financial impact onhospital by eliminating OB diversions. It was estimated that thehospital avoided going on OBdiversion 27 times during the unit’sfirst 7 months of operation.QualityImprovementDesignating specific space (room) fortriaging as well as standing ordersdid not decrease LOS. The triageprocess is strongly dependent on theprovider’s ability to assess, triage,and discharge patients.CATEGORY 6 INTERPROFESSIONIAL EDUCATION AND ADVANCED NURSING PRACTICEAngelini, D. J.,O’Brien, B.,Singer, J., &Coustan, D. R.(2012)U.S.Describes a 20-year successfulcollaborative academic practicebetween obstetrics and midwiferyin the education of residents andmedical students.Descriptive/HistoricalAnalysisMidwives in medical education are ina pivotal position to have an impacton the education of obstetricians andconsultants.Angelini, D. J.,Stevens, E.,MacDonald, A.,Wiener, S., &Wieczorek, B.(2009)U.S.Common trends in structure andfunction of four distinct models ofresident education in obstetrictriage are reviewed.Descriptive/ReviewMidwifery teaching role in obstetrictriage has expanded beyond laborassessment to include a wide range ofobstetric and gynecologic conditions.Patient safety and ability to bill forservices are additional advantages.Ciranni, P. &Essex, M. (2007)U.S.Discussion of the value of nursepractitioners in a full-serviceobstetric gynecologic triage unitregardless of gestational age.LiteratureReview/CaseExamplesNurse Practitioners can be an assetboth clinically and financially in theObGyn triage setting.Angelini, D. J.(1999a)U.S.Results of a national survey onCNMs as providers of obstetrictriage services.Survey ResearchPresenting initial benchmark data onobstetric triage units and the role ofthe CNM.Angelini, D. J.(1999b)U.S.Midwifery role in 10 triage unitsacross the country is described.Descriptive/ReviewMidwifery roles in triage have expanded, are diverse, and determined by thesetting of obstetric triage.Angelini, D. J.(2000)U.S.Reviews the history of obstetrictriage, the role dimensions ofadvanced practice nurses in triage(specifically midwives), the increased clinical risks associatedwith obstetric triage, risk reductionstrategies, and obstetric triagepractice trends and liability issuesin the future.Descriptive/ReviewObstetric triage is a rapidly growingarea of obstetric care where mostpregnancy complaints are evaluatedstarting at 20–24 weeks' gestation.This renewed interest in establishingobstetric triage units and usingadvanced practice nurses as careproviders has heightened the visibilityof obstetric triage for administratorsand practitioners alike.(continue.)290volume 39 number 5September/October 2014Copyright 2014 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Table 1. Characteristics of Triage Studies (1998–2013) (Continued.)ArticleSettingPurposeMethodologyKey Findings/HighlightsCATEGORY 7 SELECTED CLINICAL CONDITIONSLutgendorf, M. A.,Thagard, A.,Rockswold, P. D.,Busch, J. M., &Magann, E. F.(2012)U.S.Determine the prevalence ofdomestic violence (DV) in apregnant military populationpresenting for emergency obstetriccare; identify factors correlatedwith DV; and acceptability of DVscreening.Survey ResearchAngelini, D. J.(1999c)Pregnant women presenting forunscheduled emergency care werescreened for DV with Abuse Assessment Screen.U.S.Review of common nonobstetricabdominal complaints in triage.Clinical ReviewAngelini, D. J.(2003)U.S.Four of the most frequently encoun- Literaturetered nonobstetric clinical condiReviewtions warranting surgical intervention are reviewed with updates onevaluation and management.Pregnancy often masks abdominalcomplaints; provides assessment andmanagement of abdominal pain inthe triage setting.Howard, E. (2013)U.S.Review of clinical labormanagement issues.Clinical ReviewReview of evaluation and management of PROM, latent labor, activelabor, and imminent delivery.Caren, C. &Edmonson, D.(2013)U.S.Review of general surgicalemergencies.Clinical ReviewReview of evaluation and management of general surgical emergencies in pregnancy with tables forassessment of presenting complaintby abdominal quadrants.LaFontaine, D.(2013)U.S.Review of intimate partner violencein pregnancy.Clinical ReviewReview of assessment and evaluationof intimate partner violence andsexual assault with key clinicalresources itemized.The prevalence of DV in this population is higher than previouslyestimated (22.6%).Anatomic and physical changes ofpregnancy can challenge the clinicalassessment of nonobstetric conditions. Key points are reviewed toassist in accurate clinical assessmentand management of these conditions.Source: Authorsand delivery nurse who is covering the triage unit. However, state rules and regulations for advanced practiceand hospital bylaws need to be clearly reviewed to ensurecompetent credentialing of all providers and roles. Thecredentialing committee in each hospital must approvethat person to take on this role. Physician consultationmay be necessary for some advanced practice providers.The main components of EMTALA, however, center onoverall clinical evaluation and transfer of care. Anyonepresenting for care must receive an MSE. For pregnantwomen, the process requires assessment of both themother and the fetus (Angelini & Mahlmeister, 2005).Any pregnant woman must be treated and/or stabilizedfor transport. EMTALA violations carry stiff penaltiesfor hospitals and/or providers (Angelini & Mahlmeister,2005; Glass et al., 2004; Kriebs, 2013). Bitterman (2004)notes that Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS), who govern EMTALA, are concerned only ifrules regarding overall care and transfer are violated.Delay in timely response from consultants and nothaving lists of consultants available who are on-callSeptember/October 2014can also be EMTALA violations. Delay in relayingurgency to the consultant, communication issues, orunclear consultation expectations all add to delays.On-call lists, patient logs (manually or electronically),and a record of all transfers must be available uponrequest.The Technical Advisory Group of the Centers forMedicaid and Medicare implemented further recommendations to the EMTALA law in October 2006(CMS, 2006). It notes that a CNM or other QMP acting within the scope of his or her practice can certifythat a pregnant woman is not in active labor. Prior tothis, the CMS stated that only a physician could certifyprodromal and latent labor versus active labor (Angelini& Mahlmeister, 2005). Common allegations over treatment failures with EMTALA, as noted in the literature,encompass: failure to comply with EMTALA rulings,failure to perform an MSE, failure to accurately assessboth maternal and fetal status, and transferring awoman in active labor who is unstable or based on theinability to pay (Simpson & Knox, 2003).MCNCopyright 2014 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.291

Liability PitfallsGiven the rapid changes sinceEMTALA was established,liability risks and pitfalls haveemerged as key considerations.The main areas of risk assessment in obstetric triage are:assessment in a timely manner,discharge from obstetric triagewithout evidence of fetalwell-being, recognizing activelabor, timely response fromconsultants, and effective use ofclinical handoffs (Angelini,2013; Angelini & Mahlmeister,2005; Ventolini & Neiger, 2003).Assessment in a timely manner affects pregnant women whoare contracting and need to beevaluated urgently. Women whopresent with contractions and inactive labor come under the active labor component of EMTALA (particularly for patients withacute conditions such as hemorrhage or seizure activity). Avoidance of treatment delays is key.Each triage unit benefits from a standing policy onfetal assessment. This policy/guideline should not be toospecific because it must be performed with every patientto effectively meet the standard of care. All guidelinesneed to be able to govern every patient each time thescenario arises. If providers cannot meet the guideline orstandard each time, that will be problematic and presentliability concerns.Discharging a pregnant woman from an obstetrictriage unit without evidence of fetal well-being presents arisk. Failure to adequately assess the fetal heart ratetracing as well as failure to respond to a category II or IIItracing are two liability pitfalls commonly seen in theobstetric triage setting and noted in the literature. Documentation of fetal well-being prior to discharge must bein keeping with any specific triage unit guidelines.Failure to recognize active labor is another liabilitypitfall. Evaluation of active labor is part of the EMTALAact and triggers an emergency medical condition thatneeds to be assessed by a qualified medical provider. Regulations clearly state that a woman who presents withcontractions is only stable when the baby and placentaare delivered, contractions have ceased, or it is certifiedthat the pregnant woman is not in active labor. One wayto document this is to note that the patient is dischargedto home in stable condition, not in active labor. Labornurses acting in this role need to ensure they are credentialed by hospital bylaws and are within their scope ofpractice as detailed in the state nurse practice act.The most critical component in liability pitfalls is clinicalhandoffs (Angelini, 2013). Much has been written on clinical

Elisabeth Howard, PhD, CNM, FACNM Abstract Background: Triage concepts have shifted the focus of obstetric care to include obstetric triage units. The purpose of this systematic review is to examine the literature on use of triage concepts in obstetrics during a 15-year time frame. Methods: A systematic review was completed of the obstetric triage