Transcription

California’s High Housing CostsCauses and ConsequencesM A C T AY L O R LEGISLATIVEANALYST M A R C H 1 7, 2 0 1 5

AN LAO REPORT2Legislative Analyst’s Office www.lao.ca.gov

AN LAO REPORTEXECUTIVE SUMMARYCalifornia’s Home Prices and Rents Higher Than Just About Anywhere Else. Housing inCalifornia has long been more expensive than most of the rest of the country. Beginning in about1970, however, the gap between California’s home prices and those in the rest country started towiden. Between 1970 and 1980, California home prices went from 30 percent above U.S. levels tomore than 80 percent higher. This trend has continued. Today, an average California home costs 440,000, about two-and-a-half times the average national home price ( 180,000). Also, California’saverage monthly rent is about 1,240, 50 percent higher than the rest of the country ( 840 permonth).Building Less Housing Than People Demand Drives High Housing Costs. California is adesirable place to live. Yet not enough housing exists in the state’s major coastal communities toaccommodate all of the households that want to live there. In these areas, community resistance tohousing, environmental policies, lack of fiscal incentives for local governments to approve housing,and limited land constrains new housing construction. A shortage of housing along California’scoast means households wishing to live there compete for limited housing. This competition bidsup home prices and rents. Some people who find California’s coast unaffordable turn instead toCalifornia’s inland communities, causing prices there to rise as well. In addition to a shortage ofhousing, high land and construction costs also play some role in high housing prices.High Housing Costs Problematic for Households and the State’s Economy. Amid highhousing costs, many households make serious trade-offs to afford living here. Households withlow incomes, in particular, spend much more of their income on housing. High home prices herealso push homeownership out of reach for many. Faced with expensive housing options, workers inCalifornia’s coastal communities commute 10 percent further each day than commuters elsewhere,largely because limited housing options exist near major job centers. Californians are also four timesmore likely to live in crowded housing. And, finally, the state’s high housing costs make California aless attractive place to call home, making it more difficult for companies to hire and retain qualifiedemployees, likely preventing the state’s economy from meeting its full potential.Recognize Targeted Role of Affordable Housing Programs. In recent decades, the state hasapproached the problem of housing affordability for low-income Californians and those with unmethousing needs primarily by subsidizing the construction of affordable housing through bond funds,tax credits, and other resources. Because these programs have historically accounted for only a smallshare of all new housing built each year, they alone could not meet the housing needs we identify inthis report. For this reason, we advise the Legislature to consider how targeted programs that assistthose with limited access to market rate housing could supplement broader changes that facilitatemore private housing construction.More Private Housing Construction in Coastal Urban Areas. We advise the Legislature tochange policies to facilitate significantly more private home and apartment building in California’scoastal urban areas. Though the exact number of new housing units California needs to build iswww.lao.ca.gov Legislative Analyst’s Office3

AN LAO REPORTuncertain, the general magnitude is enormous. On top of the 100,000 to 140,000 housing unitsCalifornia is expected to build each year, the state probably would have to build as many as 100,000additional units annually—almost exclusively in its coastal communities—to seriously mitigateits problems with housing affordability. Facilitating additional housing of this magnitude willbe extremely difficult. It could place strains on the state’s infrastructure and natural resourcesand alter the prized character of California’s coastal communities. It also would require the stateto make changes to a broad range of policies that affect housing supply directly or indirectly—including policies that have been fundamental tenets of California government for many years.4Legislative Analyst’s Office www.lao.ca.gov

AN LAO REPORTINTRODUCTIONLiving in decent, affordable, and reasonablylocated housing is one of the most importantdeterminants of well-being for every Californian.More than just basic shelter, housing affects ourlives in other important ways, determining ouraccess to work, education, recreation, and shopping.The cost and availability of housing also mattersfor the state’s economy, affecting the ability ofbusinesses and other employers to hire and retainqualified workers and influencing their decisionsabout whether to locate, expand, or remain inCalifornia.Unfortunately, housing in California isextremely expensive. Many households struggleto find housing that is affordable and meets theirneeds. Amid this challenge, many households makeserious trade-offs in order to live here. Becauseof the important role housing plays in the lives ofCalifornians, the state’s high housing costs are amajor ongoing concern for state and local policymakers.The purpose of this report is to provide theLegislature an overview of the state’s complex andexpensive housing markets, encompassing bothsingle-family homes and multi-family apartments.We pay particular attention to identifying whathas caused housing prices to increase so quicklyin recent decades, and provide information toassist the Legislature in making decisions that willaffect the future performance of the state’s housingmarkets. The report covers four main questions: How expensive is housing in California? What has caused housing prices to increaseso quickly over the past several decadesand what would it take to moderate thistrend? What are the consequences of California’shigh housing costs on the state’shouseholds and the economy generally? What steps should the Legislature take inthe near term as it considers how to addressthe state’s high housing costs?High Housing Costs Are Not California’s OnlyHousing Challenge. Though this report focuseson high housing costs, California also faces othersignificant housing challenges meriting legislativeconsideration, including: (1) facilitating housingoptions for the state’s homeless individuals andfamilies; (2) mitigating adverse health effectsrelated to living in substandard housing or housingnear sources of pollution; and (3) removingnoneconomic barriers to housing, such as race,ethnicity, gender, and disability status. Thesechallenges are beyond the scope of this report.However, addressing the state’s high housing costs,as a broad goal, could help mitigate other housingrelated problems and thus improve the lives ofmany Californians.Information Online. Additional informationon housing in California will be posted on ourCalifornia Economy and Taxes blog (www.lao.ca.gov/LAOEconTax) in the days following thisreport’s release.HOW EXPENSIVE IS HOUSING IN CALIFORNIA?Housing Is More Expensive in CaliforniaThan Just About Anywhere Else. As shown inFigure 1 (see next page), home prices in Californiaare much higher than they are in other large states.(Among all states, only Hawaii is more expensive,on average, than California.) As of early-2015, thewww.lao.ca.gov Legislative Analyst’s Office5

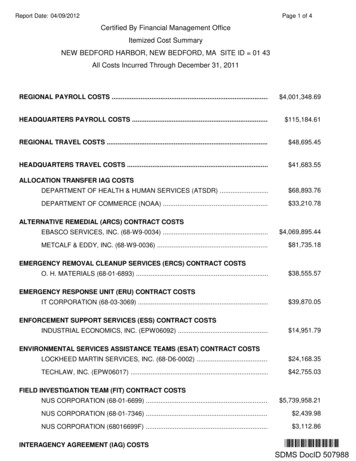

ARTWORK #140576AN LAO REPORTTemplate LAOReport large.aitFigure 1Home Prices Higher in California Than in Other Large StatesaMedian Home Value, January 2015CaliforniaMassachusettsNew JerseyWashingtonColoradoMarylandNew YorkVirginiaArizonaMinnesotaU.S. AverageFloridaIllinoisWisconsinPennsylvaniaNorth CarolinaLouisianaGeorgiaTexasSouth a100,000200,000300,000400,000 500,000a Figure shows largest 25 states according to population.typical California home cost 437,000, more thandouble the typical U.S. home ( 179,000). Californiarenters also face higher costs. In 2013, medianmonthly in California was 1,240, nearly 50 percentmore than the national average.6Legislative Analyst’s Office www.lao.ca.govHome Prices and Rents Vary Widely WithinCalifornia. In a state as large and economicallydiverse as California, some areas have much higherhome prices and rents (and other areas muchlower) than the statewide average. As shown in

AN LAO REPORTFigure 2 (see next page), for example, home pricesin California’s most expensive metropolitan area(or “metro”), San Francisco, are more than doublethe state average and about six times higher thanBakersfield, the state’s least expensive metro.(Throughout our report we use the U.S. censusdefinitions of metropolitan areas—or metros.Census metros are comprised of counties—or, insome cases, a single county—that share similarsocio-economic characteristics and surrounda common urban core.) Rents vary throughoutthe state as well. The average monthly rent for atwo-bedroom apartment in San Francisco ( 2,000)was two and a half times greater than the averagein Fresno or Bakersfield (both about 800).Even California’s Least Expensive HousingMarkets Are More Expensive Than Average.Single-family home prices and apartment rentsin less costly areas of the state, such as Fresnoand Bakersfield, though considered inexpensiveby California standards, are about averagecompared with the rest of the country. Each ofthe state’s other major metros are well-abovethe rest of nation, even California’s other majorinland metros, Riverside-San Bernardino andSacramento.California’s Home Prices and Rents HaveRisen Faster Than U.S. Average Since the 1940s.Figure 3 (see page 9) shows how average U.S. andCalifornia home prices have changed over time.In 1940, the average California home cost about20 percent more than the average U.S. home. Bythe end of the 1940s, the state’s home prices were30 percent higher than average. Over the next20 years—1950 through 1970—California homeprices increased about as quickly as the nationalaverage. Beginning in about 1970, however, homeprices throughout the state began to accelerate.Prices were 80 percent above U.S. levels by 1980,and by 2010, the typical California home was twiceas expensive as the typical U.S. home. As of 2015,average California home prices were two-anda-half times higher than average national homeprices.Many Households Have Difficulty AffordingHousing in California. As we describe in moredetail later in this report, California’s high housingcosts force many households to make serioustrade-offs. In most instances, these trade-offsare particularly challenging for households withlow incomes. Notable and widespread trade-offsinclude (1) spending a greater share of theirincome on housing, (2) postponing or foregoinghomeownership, (3) living in more crowdedhousing, (4) commuting further to work each day,and (5) in some cases, choosing to work and liveelsewhere.Government Housing Programs EaseHousing Costs for Some. Federal, state, and localgovernment housing programs generally work inone of two ways, by: (1) increasing the supply ofmoderately priced housing or (2) reducing housingcosts for some households. Programs That Build New Housing.Federal, state, and local governmentsprovide direct financial assistance—typically tax credits, grants, or low-costloans—to housing developers for theconstruction of new rental housing. Inexchange, developers reserve these units forlower-income households. (Until recently,local redevelopment agencies also providedthis type of financial assistance.) Datasuggests these programs together havesubsidized the new construction of about7,000 rental units annually in the state—orabout 5 percent of total public andprivate housing construction—since themid-1980s. In addition to direct subsidies,some local governments increase thesupply of affordable housing by requiringdevelopers of market-rate housing to setwww.lao.ca.gov Legislative Analyst’s Office7

SecretaryAnalystMPADeputyAN LAO REPORTFigure 2California's Housing Prices Vary, but Most Are Well Above U.S. LevelsAverage Monthly RentAverage Home PriceSan Francisco 952KSan Jose 843KSan Francisco 2,000Santa Ana-Anaheim 609KSan Jose 1,780Oakland 567KLos Angeles,San Diego & Oakland 1,390Santa Ana-Anaheim 1,490San Diego 471KCA Average Rent 1,240Los Angeles 490KCA Average Price 437KRiversideSan Bernardino 1,080U.S.Average 840Sacramento 950Bakersfield 820Sacramento 333KFresno 810RiversideSan Bernardino 284KFresno 188KBakersfield 170KNote: Rents based on 2013 American Community Survey. Prices reflect Zillow data, January, 2015.Template LAOReport fullpage.ait ARTWORK #1405768Legislative Analyst’s Office www.lao.ca.govU.S.Average 179K

AN LAO REPORTaside some of the units they are buildingfor low- and moderate-income households,a policy called “inclusionary housing.” low-income tenants for a portion of arental unit’s monthly cost. About400,000 Sign OffGraphicCalifornia households receive this type ofSecretaryhousing assistance. In other cases, localAnalystgovernments limit how much landlordsMPAcan increase rents each year forexistingDeputytenants. About 15 California cities havethese so-called rent controls, includingLos Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, andOakland.Programs That Help Households AffordHousing. In addition to constructing newhousing, governments have also taken stepsto make existing housing more affordable.In some cases, the federal governmentmakes payments to landlords—knownas housing vouchers—on behalf ofFigure 3California Home Prices Have Grown Much Faster Than U.S. PricesInflation-Adjusted Median Home Prices in 2015 Dollars 500,000450,000California400,000United ,000194019501960197019801990200020102015ARTWORK #140576Template LAOReport large.aitwww.lao.ca.gov Legislative Analyst’s Office9

AN LAO REPORTWHY IS HOUSING EXPENSIVE IN CALIFORNIA?A collection of factors drive California’s highcost of housing. First and foremost, far less housinghas been built in California’s coastal areas thanpeople demand. As a result, households bid up thecost of housing in coastal regions. In addition, someof the unmet demand to live in coastal areas spillsover into inland California, driving up prices theretoo. Second, land in California’s coastal areas isexpensive. Homebuilders typically respond to highland costs by building more housing units on eachplot of land they develop, effectively spreading thehigh land costs among more units. In California’scoastal metros, however, this response has beenlimited, meaning higher land costs have translatedmore directly into higher housing costs. Finally,builders’ costs—for labor, required buildingmaterials, and government fees—are higher inCalifornia than in other states. While these higherbuilding costs contribute to higher prices throughoutthe state, building costs appear to play a smaller rolein explaining high housing costs in coastal areas.This section describes how each of these factorsincrease home prices and rents in California.Building Less Housing Than PeopleDemand Drives High Housing CostsCalifornia Is Building Too Little Housing inCoastal Areas. California is a very desirable placeto live, with temperate weather, long stretchesof coastline, and highly educated and culturallydiverse economic centers. Many households wishto live in California. However, some of California’smost sought after locations—its major coastalmetros (Los Angeles, Oakland, San Diego, SanFrancisco, San Jose, and Santa Ana-Anaheim),where around two-thirds of Californians live—donot have sufficient housing to accommodate all ofthe households that want to live here. The lack ofhousing on the California coast means households10 Legislative Analyst’s Office www.lao.ca.govwishing to live there compete for limited housing.This competition bids up housing costs.Rising home prices and rents are a signal thatmore households would like to live in an area thanthere is housing to accommodate them. Housingdevelopers typically respond to this excess demandby building additional housing. This does notappear to be true, however, in California’s coastalmetros. Building activity during the recent housingboom demonstrates this. During the mid-2000s,housing prices were rising throughout the countryand, in most locations, developers responded withadditional building. As Figure 4 shows, however,new housing construction, as measured by buildingpermits issued by local officials, remained flatin California’s coastal metros. We also find thatbuilding activity in California’s coastal metroshas been significantly lower than in metrosoutside of California that have similar desirablecharacteristics—such as temperate weather, coastalproximity, and economic growth—and, therefore,likely have similar demand for housing. Forexample, Seattle—a coastal metro with economiccharacteristics and average temperatures that aresimilar to California’s Bay Area metros—addednew housing units at about twice the rate as SanFrancisco and San Jose over the last two decades.(Specifically, Seattle’s housing stock—its totalnumber of housing units—grew at an averageannual rate of 1.4 percent per year while SanFrancisco and San Jose’s housing stock grew byonly 0.7 percent per year.)Between 1980 and 2010, construction of newhousing units in California’s coastal metros was lowby national and historical standards. During this30-year period, the number of housing units in thetypical U.S. metro grew by 54 percent, comparedwith 32 percent for the state’s coastal metros. Homebuilding was even slower in Los Angeles and San

AN LAO REPORTJump in California Housing Costs OccurredGraphicas Building Slowed. A look at housingcostsSignin OffCalifornia’s coastal metros in recentdecades showsSecretarya connection between the slow rateof building andAnalysthigher housing costs. The slowdownMPAin buildingDeputyin California’s coastal metros correspondedwitha substantial rise in housing costs relative to therest of the country. In 1970, home prices in theFrancisco, where the housing stock grew by onlyaround 20 percent. As Figure 5 shows, this rateof housing growth along the state’s coast also islow by California historical standards. During anearlier 30-year period (1940 to 1970), the numberof housing units in California’s coastal metros grewby 200 percent.Figure 4Housing Construction on California Coast Was Flat During National Housing BoomAverage Number of Building Permits in Major Metros25,000California Inland20,000Rest of U.S.Graphic Sign Off15,000California 0022003200420052006Figure 5ARTWORK#140576Housing Construction Has Slowedin California'sCoastal MetrosAnnual Growth in Housing Units inTemplate LAOReport mid.aitMajor Metros6%54California InlandCalifornia Coast3Rest of U.S.211940s1950s1960s1970s1980s1990s2000sARTWORK #140576www.lao.ca.gov Legislative Analyst’s Office 11Template LAOReport mid.ait

AN LAO REPORTstate’s coastal metros were about 50 percent moreexpensive than in the rest of the country. This gap haswidened considerably since that time. Homes in thecoastal metros are now more than three times moreexpensive than the rest of the country. Similarly, rentshave grown more expensive, with the gap betweenthe coastal metros and the rest of the countryincreasing threefold since 1970 (from 16 percent moreexpensive to around 50 percent more expensive).Link Between Development and Housing CostsExists Elsewhere Too. The same relationship betweengrowth of housing supply and housing costs existsthroughout the country, suggesting that what hasoccurred in California is not coincidental. Lookingbroadly at major metropolitan counties (countiescomprising metros with a population of 500,000 orgreater) throughout the country, places with slowerhousing growth generally have more expensivehousing. Based on U.S. Census data, the medianhome price in 2010 was just over 300,000 in the fifthof counties that grew the slowest between 1980-2010,compared with 195,000 in the fifth of counties thatgrew the fastest.Our review indicates that that the relationshipbetween growth of housing supply and increasedhousing costs is complex and affected by otherfactors—such as demographics, local economies,and weather. Nonetheless, using common statisticaltechniques to account for the influence of these otherfactors, there remains a strong relationship betweenhome building and prices. For example, our analysissuggests that—after controlling for other factors—if acounty with a home building rate in the bottom fifthof all counties during the 2000s had instead beenamong the top fifth, its median home price in 2010would have been roughly 25 percent lower. Similarly,its median rent would have been roughly 10 percentlower.Spillover of Demand to Live on the Coast AffectsHousing Costs in Inland California. In contrastto the coast, more home building has occurred in12 Legislative Analyst’s Office www.lao.ca.govCalifornia’s inland metros (Bakersfield, Fresno,Riverside-San Bernardino, and Sacramento) thantypical U.S. metros. California’s inland metros addedhousing at about twice the rate of the typical U.S.metro between 1980 and 2010. Yet housing costs inmuch of inland California are above average relativeto the rest of the country. High housing costs inthe state’s inland metros appear to result largelyfrom their proximity to California’s coast. Somehouseholds and businesses that want to locate onCalifornia’s coast but find housing too expensivethere locate in California’s inland metros instead.This displaced demand places pressure on inlandhousing markets and results in higher home pricesand rents there. Examining the relationship betweenhousing costs in neighboring counties throughoutthe country using U.S. Census data from 1980 and2010, we find that this spillover effect is substantial.Our analysis suggests that—after accounting fora variety of other factors that can affect housingcosts—a 10 percent increase in housing costs in acounty is associated with a roughly 5 percent increasein housing costs in its neighboring counties.High Land Costs and Low DensityDevelopment Make Housing ExpensiveLand Costs Are High on the California Coast.Land prices on the California coast are amongthe highest in the country. In contrast, land pricesin inland California typically are at or below thenational average. Comparing land prices acrossmetropolitan areas can be difficult, largely due todata limitations. Nonetheless, several estimates ofland values are available in the economics literatureand they find that land is considerably moreexpensive on California’s coast. One analysis of landsales between 2005 and 2010 found that land pricesin California’s metros ranged from twice as expensiveas the average U.S. metro (Oakland and San Diego)to more than four times as expensive (San Francisco).We also examined existing data to better understand

AN LAO REPORTthe value of single-family home lots in different areas.Using American Housing Survey data from 2011, wefound an even greater divergence between Californiaand the rest of the country. Residential land in anaverage U.S. metro was valued at around 20,000 peracre, compared with over 150,000 in California’scoastal metros. Land values were highest in SanFrancisco, where an acre of land was valued at nearly 400,000.High Land Costs Can Be Offset Through DenseDevelopment. Although high land costs can translateinto higher home prices and rents, it is possibleto offset the effects of high land costs throughmore dense development. (The density of housingrefers to the number of housing units per unit ofland—typically measured in units per acre. Higherdensity housing, such as an apartment building,has more housing units per acre.) Building moreunits on the same plot of land allows a developer tospread land costs across more units, lessening theimpact of land costs on the cost of each unit. This isbecause land costs are fixed and do not increase ifa developer builds additional units. For example, ifa developer builds five homes on a plot of land thatcosts 100,000, the land cost per unit is 20,000.Alternatively, if the developer builds ten homeson the same plot of land, the land cost per unit isonly 10,000. Builders faced with high land costs,therefore, generally will build more dense housing.When this occurs, the effect of high land costs onhome prices and rents is reduced.Little Increase in Housing Densities in CoastalMetros. While developers typically respond to highland costs by building more dense housing, thisresponse appears to be somewhat limited in mostof California’s coastal metros. As a result, high landcosts in these areas have translated more directly intohigher housing costs. We examined U.S. Census datato compare changes in housing densities during the2000s in California’s coastal metros to changes inmetros elsewhere in the country. Our initial reviewof California’s coastal metros found that housingdensities rose significantly faster in San Franciscothan the other California coastal metros, which isunsurprising given that San Francisco’s land pricesare higher than just about anywhere else in the U.S.Because San Francisco appeared to be exceptional,we focused the rest of our review on California’sother coastal metros. We compared changes indensity in these other California coastal metros withmetros that have land prices and existing housingdensities similar to those found on California’scoast. We selected Boston, Las Vegas, Miami, Seattle,and Washington D.C. as our comparison group ofmetros. Our review found that, during the 2000s,the housing density of a typical neighborhood inCalifornia’s coastal metros rose by 4 percent. Thisincrease in density was considerably less than the11 percent average increase in our comparison group.Furthermore, we estimate that the new housing builtin these comparison metros was about 40 percentmore dense than housing built in California’scoastal metros. New housing in the comparisonmetros had an average density of about 14 unitsper acre, compared with about ten units per acre inCalifornia’s coastal metros.Building Costs Increase Housing CostsBuilding Costs Are Higher in California.Aside from the cost of land, three factors determinedevelopers’ cost to build housing: labor, materials,and government fees. All three of these componentsare higher in California than in the rest of thecountry. Construction labor is about 20 percentmore expensive in California metros than in therest of the country. California’s building codes andstandards also are considered more comprehensiveand prescriptive, often requiring more expensivematerials and labor. For example, the state requiresbuilders to use higher quality building materials—such as windows, insulation, and heating and coolingsystems—to achieve certain energy efficiency goals.www.lao.ca.gov Legislative Analyst’s Office 13

AN LAO REPORTAdditionally, development fees—charges levied onbuilders as a condition of development—are higherin California than the rest of the country. A 2012national survey found that the average developmentfee levied by California local governments (excludingwater-related fees) was just over 22,000 per singlefamily home compared with about 6,000 persingle-family home in the rest of the country. (Thissurvey reflects school facilities fees imposed duringthis period and not the higher so-called “Level 3” feesthat school districts may impose in the future if theState Allocation Board makes certain declarationsabout the availability of school construction funds.)Altogether, the cost of building a typical single-familyhome in California’s metros likely is between 50,000and 75,000 higher than in the rest of the country.Effect of Building Costs on Prices and RentsVaries Across Regions of the State. Higherbuilding costs contribute to higher housing coststhroughout the state. The relationship betweenbuilding costs and prices and rents, however,differs across inland and coastal areas of the state.In places where housing is relatively abundant,such as much of inland California, building costsgenerally determine housing costs. This is becauselandlords and home sellers compete for tenantsand homebuyers. This competition benefits rentersand prospective homebuyers by depressing pricesand rents, keeping them close to building costs.In these types of housing markets, building costsaccount for the vast majority of home prices. In twomajor inland metros—Riverside-San Bernardinoand Sacramento—building costs account for overfourth-fifths of home prices. In contrast, in coastalCalifornia, the opposite is true. Renters and homebuyers compete for a limited number of apartmentsand homes, bidding up prices far in excess of buildingSign Offcosts. Building costs account forGraphicaround one-thirdof home prices in California’s coastalmetros. UnderSecretarythese circumstances, as Figure 6Analystshows, buildingMPAcosts explain only a small portion of growth inDeputyhousing costs. Instead, increasingcompetition forlimited housing is the primary driver of housing costgrowth in coastal California.Figure 6Home Prices on California Coast Have Risen Much Faster Than Construction CostsPrices and Building Costs of Median Homes in Major Metros, 2014 dollars 1,000,000900,000800,000700,000600,000California CoastHome Price500,000400,000California CoastBuilding Cost300,000200,000100,0001985199019952000ARTWORK #140576Template LAOReport mid.ait14 Legislative Analyst’s Office www.lao.ca.gov200520102013

AN LAO REPORTWHY DO COASTAL AREAS NOTBUILD ENOUGH HOUSING?As we discussed in the last section, California’shome prices and rents have risen because housingdevelopers in California’s coastal areas have notresponded to economic signals to increase thesupply of housing and build housing at higherdensities

(or "metro"), San Francisco, are more than double the state average and about six times higher than Bakersfield, the state's least expensive metro. (Throughout our report we use the U.S. census definitions of metropolitan areas—or metros. Census metros are comprised of counties—or, in some cases, a single county—that share similar