Transcription

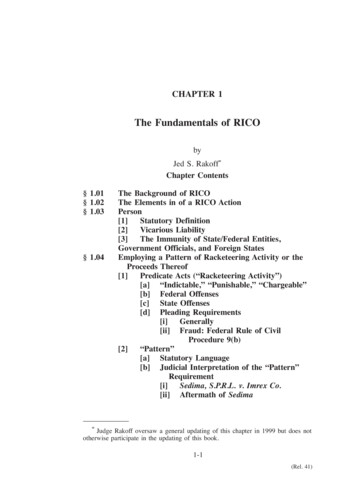

CHAPTER 1The Fundamentals of RICObyJed S. Rakoff*Chapter Contents§ 1.01§ 1.02§ 1.03§ 1.04The Background of RICOThe Elements in of a RICO ActionPerson[1]Statutory Definition[2]Vicarious Liability[3]The Immunity of State/Federal Entities,Government Officials, and Foreign StatesEmploying a Pattern of Racketeering Activity or theProceeds Thereof[1]Predicate Acts (“Racketeering Activity”)[a] “Indictable,” “Punishable,” “Chargeable”[b] Federal Offenses[c] State Offenses[d] Pleading Requirements[i]Generally[ii] Fraud: Federal Rule of CivilProcedure 9(b)[2]“Pattern”[a] Statutory Language[b] Judicial Interpretation of the “Pattern”Requirement[i]Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co.[ii] Aftermath of Sedima*Judge Rakoff oversaw a general updating of this chapter in 1999 but does nototherwise participate in the updating of this book.1-1(Rel. 41)

RICO: CIVIL AND CRIMINAL§ 1.05§ 1.06§ 1.07§ 1.081-2[iii] “Mailings” vs. “Episodes” vs.“Schemes”[iv] “Continuity” and “Relationship” vs.“Distinctiveness”[c] H.J., Inc. and Its AftermathThe “Enterprise”[1]“Associated in Fact” Enterprises[2]Test to Establish Existence of an Enterprise:Associations in Fact[3]Distinction Between Enterprise and Defendant[4]Economic Motive[5]Types of Enterprises[a] Legitimate Business Entities[b] Illegal Enterprises[c] Individuals[d] Labor Unions[e] Governmental Entities[f] Foreign Corporations[6]Effect on Interstate or Foreign Commerce[7]Avoiding the Enterprise/Person IdentityProblemsActivities Prohibited Under the Act[1]Investment of the Proceeds[2]Acquiring an Interest in or Control of anEnterprise[a] Interest[b] Control[3]Conducting the Affairs of an Enterprise[a] The “Operation or Management” Test[b] Reves v. Ernst & Young[c] The Reves Majority’s Analysis[d] Certain Implications of Reves[e] Pre-Reves Decisions[4]ConspiracyInjury[1]Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co.[2]Standing for Private Individuals Who CanShow Injury[3]Standing to Bring Conspiracy Claims[4]Injury to Business or Property[5]The Filed Rate Doctrine[6]Causation NexusSanctions and Remedies[1]Criminal Sanctions

1-3FUNDAMENTALS OF RICO[2][3]§ 1.01Civil Remedies[a] Equitable Relief for Private Parties[b] Punitive Damages and Contribution[c] Rule 11 Sanctions[d] ArbitrationGovernment Civil RICO§ 1.01 The Background of RICOSince its enactment in 1970, the Racketeer Influenced and CorruptOrganizations Act (“RICO”)1 has been one of the most controversialof federal statutes. Its criminal provisions are both novel and stringent, and apply to a greater range of conduct than any other criminallaw. Its private civil provisions not only expand the scope of federalcivil jurisdiction to cover most business torts but also materially alterthe balance of power between plaintiffs and defendants. And underRICO’s so-called “government civil” provisions, the state can assertcontrol over entire businesses and organizations.During the 1990s many of the fundamental questions regardingRICO’s scope and power were resolved. Nevertheless, the statuteremains difficult to apply because its terms are artificial and not easily correlated with everyday experiences. The main purpose of thischapter is to facilitate a basic understanding of RICO by describingits fundamentals.To appreciate what RICO has become, one must first understandits derivation. RICO’s origins were rather modest. RICO was simplyone title, Title IX, of the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970,2 abroad-based statute intended to combat the influence of organizedcrime in interstate and foreign commerce. Although the entire Organized Crime Control Act was controversial, most of the public debatecentered on its expanded wiretap provisions3 and its simplification ofthe granting of immunity.4 As a result, the particularized legislativehistory of many of RICO’s provisions is sparse.Generally, however, Congress enacted RICO in response to a fearof infiltration of legitimate commercial enterprises by traditional1Pub. L. No. 91-452, 84 Stat. 941 (1970) (codified at 18 U.S.C. §§ 1961-1968(1982), as amended by the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984, Pub. L. No.98-473, §§ 302, 901, 1020, 2301, 98 Stat. 1837, 2040-2044, 2136, 2143, 2192).2Pub. L. No. 91-452, 84 Stat. 922 (1970) (codified as amended in scattered sections of 18 U.S.C.).3Now largely codified at 18 U.S.C. §§ 2510-2522.4See 18 U.S.C. §§ 6001 et seq.(Rel. 45)

§ 1.01RICO: CIVIL AND CRIMINAL1-4“organized crime” associations, a concern that dates back at least tothe time of the Kefauver Committee hearings in the early 1950s.5During the early 1960s, hearings before the McClellan Committee—and especially the testimony of Joseph Valachi regarding “La CosaNostra”—increased public concern about the impact of organizedcrime on ordinary commercial activities. In 1967, the Senate responded by proposing two bills that would enhance the penalties for certain organized crime activities in commercial ventures.6 AlthoughCongress did not act on either bill, the hearings regarding the billseventually spawned the first real version of RICO,7 which the Senateconsidered in 1969: an act designed to prevent “known mobsters”from infiltrating legitimate businesses.8 To avoid any constitutionalprohibition against a crime of status, however, the proposal focusedon whether the infiltration of a legitimate enterprise was derived fromor implemented by a “pattern of racketeering activity,”9 rather than onthe status of the person infiltrating the business. To assure nonetheless that the statute covered every kind of “mob” infiltration of legitimate business, Congress defined “racketeering activity” broadly toinclude a long list of state and federal predicate crimes commonlycommitted by mobsters and other career criminals.10This approach caused some of those following the development ofthe statute to worry that it might be constitutionally defective becauseit was overbroad. Original drafts of the legislation sought to minimizesuch concerns by vesting enforcement of both the statute’s criminaland civil provisions exclusively with the government.11 When the billreached the House of Representatives, however, that chamber offereda number of amendments, including a private, civil, treble-damageprovision “similar to the private damage remedy found in the antitrustlaws.”12 The House passed the amendment with little debate, and without seriously considering whether it meshed with the rest of the bill.135See generally, Lynch, “RICO: The Crime of Being a Criminal, Parts I and II,”87 Columbia L. Rev. 661, 661-713 (1987) (discussing the origins and developmentof RICO).6S. 2048 and S. 2049, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. (1967).7S. 30, 91st Cong., 1st Sess. (1969).8S. Rep. 91-617, at 76 (1969).918 U.S.C. § 1961(5).1018 U.S.C. § 1961(1).11See Blakey and Gettings, “Racketeer and Corrupt Organizations (RICO): BasicConcepts—Criminal and Civil Remedies,” 53 Temple L. Q. 1009, 1017-1019 (1980).12Hearings on S. 30, and Related Proposals, Before Subcomm. No. 5 of theHouse Comm. on the Judiciary, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. 520 (1970) (statement of Rep.Steiger) (quoted in Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co., 473 U.S. 479, 487, 105 S.Ct. 3275,87 L.Ed.2d 346 (1985)).13See Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co., 473 U.S. 479, 487-488, 105 S.Ct. 3275, 87L.Ed.2d 346 (1985).

1-5FUNDAMENTALS OF RICO§ 1.01After the House passed the amended bill, Congress did not send itto a conference because elections were approaching and the sessionwas almost over. Instead, the bill was returned to the Senate, whichpassed the House-amended version without further debate.14 On October 15, 1970 President Nixon signed RICO, Title IX of the OrganizedCrime Control Act, into law.Although RICO’s stated purpose was “the elimination of the infiltration of organized crime and racketeering into legitimate organizations operating in interstate commerce,”15 its language was not limited accordingly, and as a result the courts have not thus limited itsapplication but have applied RICO to a wide variety of persons16 andsituations17 that the enacting Congress did not envision. RICO’s evo-14Blakey and Gettings, N. 11 supra, Temple L. Q. at 1021.S. Rep. No. 91-617, 91st Cong., 1st Sess. 161, at 76 (1969). See, e.g., UnitedStates v. Boylan, 620 F.2d 359, 361 (2d Cir. 1980).16See, e.g.:First Circuit: Micro-Medical Industries v. Hatton, 607 F. Supp. 931, 938 (D.P.R.1985).Second Circuit: Moss v. Morgan Stanley, Inc., 719 F.2d 5, 21 (2d Cir. 1983).Third Circuit: United States v. Vignola, 464 F. Supp. 1091, 1095-1096 (E.D. Pa.1979), aff’d 605 F.2d 1199 (3d Cir. 1979).Fourth Circuit: United States v. Mandel, 415 F. Supp. 997, 1018-1019 (D. Md.1976).Fifth Circuit: Owl Construction Co. v. Ronald Admas Contractor, Inc., 727 F.2d540, 542 (5th Cir. 1984).Sixth Circuit: Austin v. Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc., 570 F. Supp.667, 669-670 (W.D. Mich. 1983).Seventh Circuit: Bunker Ramo Corp. v. United Business Forms, Inc., 713 F.2d1272, 1287 n.6 (7th Cir. 1983).Eighth Circuit: Bennett v. Berg, 685 F.2d 1053, 1063-1064 (8th Cir. 1982), aff’din part, rev’d in part, and remanded on other grounds on reh’g en banc 710 F.2d1361 (8th Cir. 1983).Ninth Circuit: United States v. Campanale, 518 F.2d 352, 363-364 (9th Cir. 1975).But see, Hokama v. E. F. Hutton & Co., 566 F. Supp. 636, 642-644 (C.D. Cal. 1983)(requiring plaintiff to allege a connection to organized crime in civil RICO cases).Eleventh Circuit: United States v. Gottesman, 724 F.2d 1517, 1521 (11th Cir.1984).17See, e.g.:Third Circuit: Perlberger v. Perlberger, 1998 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 1964 (E.D. Pa.Feb. 24, 1998) (refusing to dismiss, on policy grounds, a RICO claim arising out ofa divorce proceeding and rejecting the argument that the racketeering activitiesembraced by the statute must include crimes traditionally associated with the transgressions of racketeers).Sixth Circuit: Austin v. Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc., 570 F. Supp.667, 668-670 (W.D. Mich. 1983) (applying RICO in commercial fraud context).Seventh Circuit: Illinois Dep’t of Revenue v. Phillips, 771 F.2d 312 (7th Cir.1985) (applying RICO to mailing of fraudulent tax returns); United States v. Aleman,609 F.2d 298 (7th Cir. 1979) (applying statute to burglaries in two states by defendants not affiliated with organized crime).15(Rel. 45)

§ 1.01RICO: CIVIL AND CRIMINAL1-6lution reflects a tension between the statute’s often-praised use as aninnovative weapon against large-scale criminal enterprises and itsoften-criticized employment as a springboard for dubious privateactions.18 Reflecting this tension, courts have usually construed theact more broadly when the government is the proponent than whenthe plaintiff is a private party. Moreover, the lower federal courts,where dockets are more directly affected, have sometimes attemptedto erect barriers to the private use of RICO, only to have these limitations removed by higher federal courts applying the plain and verybroad language of the statute.19For example, in the late 1970s and early 1980s some lower courtsreacted to the seeming overextension of civil RICO20 by fashioning anumber of judicially created standing requirements for its use, notably18See, e.g.:Second Circuit: Schmidt v. Fleet Bank, 16 F. Supp.2d 340, 346 (S.D.N.Y. 1998)(“[C]ourts must always be on the lookout for the putative RICO case that is reallynothing more than an ordinary fraud case clothed in the Emperor’s trendy garb.”)(citation omitted); Toms v. Pizzo, 4 F. Supp.2d 178, 182 (W.D.N.Y. 1998) (“[RICO]was not intended to reach ‘every act of corruption or petty crime committed in a business setting.’”) (citation omitted); Mathon v. Marine Midland Bank, 875 F. Supp.986, 1001 (E.D.N.Y. 1995) (“[T]he purposes of civil RICO liability do not includedeterrence of unlawful acts, not rising to criminal liability, for which there are stateand common law remedies.”).Third Circuit: Tabas v. Tabas, 47 F.3d 1280, 1296 (3d Cir. 1995) (en banc) (“[W]erecognize that our ruling means that RICO . . . may be applicable to many ‘gardenvariety’ fraud cases.”). (Citation omitted).Seventh Circuit: Williams v. Aztar Indiana Gaming Corp., 351 F.3d 294 (7th Cir.2003) (claim of mail fraud against casino arising from its mailings to a compulsivegambler was frivolous and classifying the plaintiff’s attempt to use the statute toprosecute his state law claim as “exactly the type of bootstrapping use of RICO thatthe federal courts abhor.”); Uniroyal Goodrich Tire Co. v. Mutual Trading Corp., 63F.3d 516, 522 (7th Cir. 1995) (“The murkiness of RICO’s parameters coupled withits alluring remedies have led many plaintiffs to take garden variety business disputesand dress them up as elaborate racketeering schemes.”).District of Columbia Circuit: Yellow Bus Lines, Inc. v. Drivers, Chauffeurs &Helpers Local Union 639, 913 F.2d 948, 954 (D.C. Cir. 1990) (RICO was not intended to reach minor business corruption and crime).19See Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co., 473 U.S. 479, 488-500, 105 S.Ct. 3275, 87L.Ed.2d 346 (1985).20See, e.g.:Second Circuit: Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co., 741 F.2d 482, 487 (2d Cir. 1984),rev’d 473 U.S. 479, 105 S.Ct. 3275, 87 L.Ed.2d 346 (1985) (private, civil RICO hasbeen put to extraordinary and outrageous uses and has led to claims against legitimate businesses rather than mobsters).Ninth Circuit: Hokama v. E. F. Hutton & Co., 566 F. Supp. 636, 642-644 (C.D.Cal. 1983) (requiring plaintiffs to allege some link to organized crime in civil RICOcases).Eleventh Circuit: Taylor v. Bear Stearns & Co., 572 F. Supp. 667, 681-683 (N.D.Ga. 1983) (discussing various judicially created limits to RICO suits).

1-7FUNDAMENTALS OF RICO§ 1.01proof of a “racketeering injury,”21 a “competitive injury,”22 or a “priorconviction.”23 In Sedima, S.P.R.L. v Imrex Co.,24 however, theSupreme Court, in a 5 to 4 decision, struck down these requirementson the ground that they went well beyond the plain language of thestatute.25 Although the Sedima majority invited Congress to amendRICO to conform its use to the original intent of the legislation, Congress has only taken modest steps in this direction.26 Thus, much ofthe underlying tension that caused the Supreme Court to divide 5 to4 in Sedima remains.27Nonetheless, neither RICO’s constitutionality28 nor its broad scopecurrently appears to be in serious jeopardy, and the courts have shift21See, e.g., Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co., 741 F.2d 482, 487 (2d Cir. 1984).See, e.g., North Barrington Development, Inc. v. Fanslow, 547 F. Supp. 207,210 (N.D. Ill. 1980).23See, e.g., Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co., N. 21 supra, 741 F.2d at 496-504.24Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co., 473 U.S. 479, 105 S.Ct. 3275, 87 L.Ed.2d 346(1985). Justice White’s majority opinion was joined by Chief Justice Burger and Justices Rehnquist, Stevens, and O’Connor.25Id., 473 U.S. at 488-500. Justice Marshall, in a dissent joined by Justices Brennan, Blackmun, and Powell, stressed that the standing requirements brought thestatute into closer accord with the original legislative intent. Id. at 500-523 (Marshall,J., dissenting). Justice Powell, in a separate dissent, argued that the majority’s reading of the statute was so broad as to vitiate the main limitation of the scope of RICOcontained in its actual language, i.e., its limitation to misconduct resulting from a“pattern of racketeering activity.” Id. at 523-530 (Powell, J., dissenting).26See Private Securities Litigation Reform Act, Pub. L. No. 104-67, 109 Stat. 737(1997) (codified at 15 U.S.C. § 78u-4) (eliminating conduct that would have beenactionable as fraud in the purchase or sale of securities as a predicate act under§ 1961).27Although the Supreme Court’s subsequent RICO decision in H. J., Inc. v.Northwestern Bell Telephone Co., 492 U.S. 229, 109 S.Ct. 2893, 106 L.Ed.2d 195(1989), was unanimous in reversing the lower court, the Court remained deeplydivided in its view of RICO. Four concurring justices expressed the view that RICOis unconstitutionally vague. Id. at 251 (Scalia, J., concurring). See also, Firestone v.Galbreath, 747 F. Supp. 1556, 1579-1581 (S.D. Ohio 1990), aff’d 976 F.2d 279 (6thCir. 1992) (RICO unconstitutionally vague as applied to defendants).28See, e.g.:First Circuit: United States v. Oreto, 37 F.3d 739 (1st Cir. 1994) (rejecting argument that the continuity plus relationship test for a pattern under section 1962(c) isunconstitutionally vague); United States v. Angiulo, 897 F.2d 1169, 1178-1180 (1stCir. 1990) (RICO was not unconstitutionally vague as applied to defendants).Second Circuit: Bingham v. Zolt, 66 F.3d 553, 566 (2d Cir. 1995) (pattern andenterprise requirements were not unconstitutionally vague).Third Circuit: United States v. Woods, 915 F.2d 854, 862-864 (3d Cir. 1990)(RICO was not unconstitutionally vague as applied to defendants convicted of extortion and other criminal conduct involving political corruption); United States v. Pungitore, 910 F.2d 1084, 1102-1105 (3d Cir. 1990) (statute was constitutional as appliedto activities of organized crime).Fourth Circuit: United States v. Bennett, 984 F.2d 597, 605-607 (4th Cir. 1993)(pattern requirement was not unconstitutionally vague in insurance fraud situation).22(Rel. 45)

§ 1.01RICO: CIVIL AND CRIMINAL1-8ed their attention to other ways of separating legitimate and illegitimate RICO claims.For example, in Humana Inc. v. Forsyth,29 the Supreme Courtaddressed the issue of whether RICO’s scope was limited by theMcCarran-Ferguson Act,30 which provides:“No Act of Congress shall be construed to invalidate, impair, orsupersede any law enacted by any state for the purpose of regulating the business of insurance . . . unless such Act specificallyrelates to the business of insurance.”31In the past, various circuit courts reached different conclusionsregarding whether the McCarran-Ferguson Act barred federal RICOclaims.32 In Humana, the Court initially found that “RICO is not aFifth Circuit: United States v. Krout, 66 F.3d 1420, 1432 (5th Cir. 1995) (patternrequirement was not unconstitutionally vague as applied to member of the Mexicanmafia); United States v. Aucoin, 964 F.2d 1492, 1497-1398 (5th Cir. 1992) (RICOwas not unconstitutionally vague).Sixth Circuit: Columbia Natural Resources v. Tatum, 58 F.3d 1101, 1104-1109(6th Cir. 1995) (rejecting claim that the phrase “pattern of racketeering activity” wasvoid for vagueness as applied to defendants).Seventh Circuit: United States v. Korando, 29 F.3d 1114, 1119 (7th Cir. 1994)(RICO was not unconstitutionally vague because it is a remedial statute that does notmake criminal activity that was otherwise legal); National Organization for Women,Inc. v. Scheidler, 897 F. Supp. 1047, 1089-1091 (N.D. Ill. 1995) (RICO was neithervague nor overbroad; rejected constitutional challenge).Eighth Circuit: United States v. Keltner, 147 F.3d 662, 667 (8th Cir. 1998) (pattern and enterprise requirements were not unconstitutionally vague).Ninth Circuit: United States v. Frega, 179 F.3d 793, 800-801 (9th Cir. 1999)(rejecting Commerce Clause challenge to RICO); United States v. Blinder, 10 F.3d1468, 1475 (9th Cir. 1993) (rejecting vagueness challenge to RICO); United Statesv. Freeman, 6 F.3d 586, 597-598 (9th Cir. 1993) (term “enterprise” was not unconstitutionally vague as applied to defendant).Tenth Circuit: United States v. Hayworth, 941 F. Supp. 1057, 1060 (D.N.M. 1996)(pattern and enterprise requirements were not void for vagueness as applied to defendants in drug distribution scheme); Schrag v. Dinges, 788 F. Supp. 1543, 1552-1555(D. Kan. 1992) (RICO was not unconstitutionally vague as applied to mail fraudscheme).Eleventh Circuit: Cox v. Administrator, United States Steel & Carnegie, 17 F.3d1386, 1398 (11th Cir. 1994) (RICO was not unconstitutionally vague), modified 30F.3d 1347 (11th Cir. 1994).District of Columbia Circuit: Dooley v. United Technologies Corp., 1992 U.S.Dist. LEXIS 8653 (D.D.C. June 16, 1992) (RICO not unconstitutionally vague).29Humana Inc. v. Forsyth, 525 U.S. 299, 119 S.Ct. 710, 142 L.Ed.2d 753 (1999).3015 U.S.C. §§ 1011, et seq.3115 U.S.C. § 1012(b).32The Fourth, Sixth, and Eighth Circuits adopted the “upset the balance”approach, reasoning that the McCarran-Ferguson Act barred federal RICO claimsbecause otherwise, RICO would invalidate and supersede state remedies and regulatory supervision. See, e.g.:

1-9FUNDAMENTALS OF RICO§ 1.01law that ‘specifically relates to the business of insurance,’” and wenton to address the key issue of whether applying RICO to the casebefore it would “invalidate, impair, or supercede Nevada’s laws regulating insurance.”33 The Court reached the following formulation:“When federal law does not directly conflict with state regulation, and when application of the federal law would not frustrateany declared state policy or interfere with a State’s administrativeregime, the McCarran-Ferguson Act does not preclude its application.”34The Court in this case concluded that, applying RICO to the casebefore it did not conflict with the McCarran-Ferguson Act “[b]ecauseRICO advances the State’s interest in combating insurance fraud, anddoes not frustrate any articulated Nevada policy.”35Most courts addressing the issue after Humana have found that theMcCarran-Ferguson Act did not prohibit the application of RICO tothe cases before them.36 Clearly, however, the Court’s decision doesFourth Circuit: Ambrose v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Virginia, Inc., 891 F.Supp. 1153 (E.D. Va. 1995), aff’d 95 F.3d 41 (4th Cir. 1996).Sixth Circuit: Kenty v. Bank One, Columbus, N.A., 92 F.3d 384 (6th Cir. 1996).Eighth Circuit: Doe v. Norwest Bank Minnesota, N.A., 107 F.3d 1297 (8th Cir.1997).The First, Third, Seventh, and Ninth Circuits adopted the “direct conflictapproach,” reasoning that the McCarran-Ferguson Act does not preclude the application of RICO or other federal statutes prohibiting acts that are also prohibited by stateinsurance laws. See, e.g.:First Circuit: Villafane-Neriz v. FDIC, 75 F.3d 727 (1st Cir. 1996).Third Circuit: Sabo v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., 137 F.3d 185 (3d Cir.1998).Seventh Circuit: Autry v. Northwest Premium Services, Inc., 144 F.3d 1037 (7thCir. 1998); National Ass’n for the Advancement of Colored People v. American Family Mutual Insurance Co., 978 F.2d 287 (7th Cir. 1992).Ninth Circuit: Forsyth v. Humana Inc., 114 F.3d 1467 (9th Cir. 1997).33Humana Inc. v. Forsyth, 525 U.S. 299, 119 S.Ct. 710, 142 L.Ed.2d 753 (1999).The Court defined “invalidate” as “to render ineffective, generally without providinga replacement rule or law,” and “supersede” as “to displace (and thus render ineffective) while providing a substitute rule.” The Court concluded that applying RICOto the case before it “would neither ‘invalidate’ nor ‘supersede’ Nevada law.”The Court also questioned whether applying RICO would “impair” Nevada’s law.It looked to the definition of “impair” in Black’s Law Dictionary (“[t]o weaken, tomake worse, to lessen in power, diminish, or relax, or otherwise affect in an injurious manner”).34Id., 525 U.S. at 309.35Id., 525 U.S. at 313.36See, e.g.:Third Circuit: Weiss v. First Unum Life Insurance Co., 482 F.3d 254, 269 (3d Cir.2007).Fourth Circuit: American Chiropractic Ass’n, Inc. v. Trigon Healthcare, Inc., 367F.3d 212, 222 (4th Cir. 2004).(Rel. 45)

§ 1.01RICO: CIVIL AND CRIMINAL1-10not stand for the proposition that the McCarran-Ferguson Act willnever prohibit RICO claims involving insurance.37Sixth Circuit: Brown v. Cassens Transport Co., 546 F.3d 347, 357-363 (6th Cir.2008) (a state worker’s compensation statute did not reverse preempt RICO under theMcCarran-Ferguson Act).Seventh Circuit: Shapo v. Engle, 1999 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 17966, at *33-*40 (N.D.Ill. Nov. 12, 1999).Eighth Circuit: Cunningham v. PFL Life Insurance Co., 42 F. Supp.2d 872, 881882 (N.D. Iowa 1999).Tenth Circuit: Bancoklahoma Mortgage Corp. v. Capital Title Co., Inc., 194 F.3d1089 (10th Cir. 1999).37See, e.g.: LaBarre v. Credit Acceptance Corp., 175 F.3d 640, 642-643 (8th Cir.1999) (applying Humana, the McCarran-Ferguson Act allowed plaintiff’s RICOclaims against one defendant, but prohibited RICO claims against other defendants);Doe v. Norwest Bank Minnesota, N.A., 107 F.3d 1297 (8th Cir. 1997).

1-11§ 1.02FUNDAMENTALS OF RICO§ 1.02The Elements of a RICO ActionDespite its many complexities and intricacies, RICO has at its core afairly simple design: it prohibits a person1 from utilizing a pattern of unlawful activities to infiltrate an interstate enterprise.2 This design reflectslegislative findings that mobsters were infiltrating legitimate businessesthrough racketeering activities or the proceeds derived therefrom. However, given the statute’s more general wording, it has been applied wellbeyond the historical circumstances that motivated its enactment.Although courts often speak of a RICO cause of action as requiringsix, eight, or more essential elements,3 in fact the elements can basicallybe reduced to four. Specifically, in order to state a RICO violation, acriminal indictment4 or civil complaint5 must at least allege:(1) that a “person” within the scope of the statute(2) has utilized a “pattern of racketeering activity” or the proceedsthereof(3) to infiltrate an interstate “enterprise”(4) by (a) investing the income derived from the pattern of racketeering activity in the enterprise; (b) acquiring or maintaining an interest in the enterprise through the pattern of racketeering activity; (c)conducting the affairs of the enterprise through the pattern of racketeering activity; or (d) conspiring to commit any of the above acts.6A plaintiff in a private, civil RICO action must also allege that he orshe sustained an injury to his business or property “by reason of” one ofthe foregoing.7 Each of these elements is discussed in subsequent sections.1Under RICO, a person “includes any individual or entity capable of holding a legalor a beneficial interest in property.” 18 U.S.C. § 1961(3).218 U.S.C. § 1962.3See, e.g., Moss v. Morgan Stanley, Inc., 719 F.2d 5, 17 (2d Cir. 1983).418 U.S.C. § 1963.518 U.S.C. § 1964.618 U.S.C. § 1962.718 U.S.C. § 1964(c).(Rel. 45)

§ 1.03[1]RICO: CIVIL AND CRIMINAL1-12§ 1.03 Person[1]—Statutory DefinitionSection 1961(3) of RICO defines “person” to include “any individual or entity capable of holding a legal or beneficial interest inproperty,”1 and this definition applies both to putative RICO plaintiffsand defendants. Corporations and partnerships plainly fall within thisdefinition, but courts have also found unincorporated associations,which are capable of holding a legal or beneficial interest in property, to be liable under RICO.2 Unions and public utilities are also within RICO’s definition of “person.”3 Ironically, the Second Circuit hasdetermined that an organized crime family, and specifically “La CosaNostra,” is not a RICO “person.”4 Although most state and local governments qualify as RICO “persons” because they can hold property,they are frequently immune from RICO liability on other grounds.5Courts are divided as to whether a civil RICO claim survives thedeath or dissolution of a “person” liable under RICO. The divisiondepends on whether the court views RICO’s treble-damage provisionas remedial, in which case the claim survives,6 or penal, in which118 U.S.C. § 1961(3).See Jund v. Town of Hempstead, 941 F.2d 1271, 1281-1282 (2d Cir. 1991).3See, e.g.:Second Circuit: County of Suffolk v. Long Island Lighting Co., 907 F.2d 1295,1305-1308 (2d Cir. 1990) (public utility).Third Circuit: United States v. Local 30, United Slate, Tile, and CompositionRoofers, Damp and Waterproof Workers Ass’n, 686 F. Supp. 1139, 1165 (E.D. Pa.1988) (unions and union officers).Eleventh Circuit: Taffet v. Southern Co., 930 F.2d 847, 852 (11th Cir. 1991)(RICO was applicable to utilities because they are legal entities capable of holdingproperty), reh’g en banc granted 958 F.2d 1514 (11th Cir. 1992), RICO claims dismissed on other grounds en banc 967 F.2d 1483, 1486-1494 (11th Cir. 1992).4United States v. Bonanno Organized Crime Family, 879 F.2d 20 (2d Cir. 1989).5See § 1.03[3] infra. See also, Attorney General of Canada v. R.J. ReynoldsTobacco Holdings, Inc., 103 F. Supp.2d 134, 146-150 (N.D.N.Y. 2000) aff’d on othergrounds 268 F.3d 103 (2d Cir. 2001) ( determining that Canada, the plaintiff in thelitigation, was a person within the meaning of § 1961(3)).6See, e.g.:Second Circuit: Jerry Kubecka, Inc. v. Avellino, 898 F. Supp. 963, 968 (E.D.N.Y.1995) (“RICO claims survive the death of a plaintiff”); Costello v. Cooper, 1990 U.S.Dist. LEXIS 946 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 30, 1990).Fourth Circuit: Faircloth v. Finesod, 938 F.2d 513, 518 (4th Cir. 1991).Sixth Circuit: County of Oakland v. City of Detroit, 784 F. Supp. 1275, 1284-1285(E.D. Mich. 1992).Seventh Circuit: State Farm Fire & Casualty Co. v. Estate of Caton, 540 F. Supp.673, 681-682 (N.D. Ind. 1982). But see, Ball v. Marshall Field V, 1993 U.S. Dist.LEXIS 4273 at *29 (N.D. Ill. April 2, 1993) (treble-damage provision penal; courtabated plaintiff’s claim).2

1-13FUNDAMENTALS OF RICO§ 1.03[2]case the claim abates.7 As to whether one may be liable for anotherperson’s RICO violations if one succeeds that person in interest, thecase law, though limited, appears to apply the conventional principlesof successor liability found in other tort contexts, holding a successorliable if the successor has actual or constructive knowledge of thepredecessor’s illegal acts.8[2]—Vicarious LiabilityAs a general rule of agency, a principal is liable for harm causedby the principal’s agents when the agents were acting within thescope of their employment or apparent authority.9 By and large, thecourts have applied general agency principles to RICO cases despitelanguage in the statute that could be construed as disfavoring vicarious liability.10There are, however, certain nuances regarding vicarious liabilitythat are peculiar to RICO. The most significant arises in connectionwith claims brought under Section 1962(c), which prohibits any “person” who is “employed by or associate

The Fundamentals of RICO by Jed S. Rakoff* Chapter Contents § 1.01 The Background of RICO § 1.02 The Elements in of a RICO Action § 1.03 Person [1] Statutory Definition [2] Vicarious Liability [3] The Immunity of State/Federal Entities, Government Officials, and Foreign States § 1.04 Employing a Pattern of Racketeering Activity or the .