Transcription

#ACcyberISSUE BRIEFA Primer on theProliferation ofOffensive CyberCapabilitiesMARCH 2021THE SCOWCROFT CENTER FORSTRATEGY AND SECURITY worksto develop sustainable, nonpartisanstrategies to address the mostimportant security challenges facingthe United States and the world.The Center honors General BrentScowcroft’s legacy of service andembodies his ethos of nonpartisancommitment to the cause of security,support for US leadership incooperation with allies and partners,and dedication to the mentorship ofthe next generation of leaders.THE CYBER STATECRAFT INITIATIVEworks at the nexus of geopolitics andcybersecurity to craft strategies tohelp shape the conduct of statecraftand to better inform and secure usersof technology. This work extendsthrough the competition of state andnon-state actors, the security of theinternet and computing systems, thesafety of operational technology andphysical systems, and the communitiesof cyberspace. The Initiative convenesa diverse network of passionate andknowledgeable contributors, bridgingthe gap among technical, policy, anduser communitiesWINNONA DESOMBRE, MICHELECAMPOBASSO, LUCA ALLODI,JAMES SHIRES, JD WORK, ROBERTMORGUS, PATRICK HOWELL O’NEILL,AND TREY HERREXECUTIVE SUMMARYOffensive cyber capabilities run the gamut from sophisticated, long-termdisruptions of physical infrastructure to malware used to target human rightsjournalists. As these capabilities continue to proliferate with increasingcomplexity and to new types of actors, the imperative to slow and counter theirspread only strengthens. But to confront this growing menace, practitioners andpolicy makers must understand the processes and incentives behind it. Theissue of cyber capability proliferation has often been presented as attemptedexport controls on intrusion software, creating a singular emphasis on malwarecomponents. This primer reframes the narrative of cyber capability proliferationto be more in line with the life cycle of cyber operations as a whole, presentingfive pillars of offensive cyber capability: vulnerability research and exploitdevelopment, malware payload generation, technical command and control,operational management, and training and support. The primer describes howgovernments, criminal groups, industry, and Access-as-a-Service (AaaS) providerswork within either self-regulated or semi-regulated markets to proliferate offensivecyber capabilities and suggests that the five pillars give policy makers a moregranular framework within which to craft technically feasible counterproliferationpolicies without harming valuable elements of the cybersecurity industry. Theserecommended policies are developed in more detail, alongside three case studiesof AaaS firms, in our companion report, Countering Cyber Proliferation: Zeroing inon Access as a Service.

#ACcyberA PRIMER ON THE PROLIFERATION OF OFFENSIVE CYBER CAPABILITIESINTRODUCTIONThe proliferation of offensive cyber capabilities (OCC)has often been compared with nuclear proliferation andstockpiling. Nuclear and cyber are two very differentthreats, especially in their regulatory maturities, but in bothof them a multitude of bilateral and multilateral treaties havebeen created and then sidestepped, acceded to, expanded,and abandoned like steps in a dance. Regulatory and policyaspects in the OCC domain are particularly difficult due tothe elusive nature of cyber capabilities, and the difficultyof measuring them, especially in the absence of a clearframework that defines and maps them to the broader pictureof international equilibria. Offensive cyber capabilitiesare not currently cataclysmic, but are instead quietly andpersistently pernicious. The barrier to entry in this domainis much more of a gradual rise than a steep cliff, and thisslope is expected to only flatten increasingly over time.1 Asstates and non-state actors gain access to more and betteroffensive cyber capabilities, and the in-domain incentives touse them,2 the instability of cyberspace grows. Furthermore,kinetic effects resulting from the employment of offensivecyber capabilities, the difficulties in the attribution processof attacks caused by an invisible militia, and the lack ofmature counterproliferation regimes bring the problem to ageopolitical scale.Creating a counterproliferation regime in cyberspace hasconfounded policy makers for over a decade. As the numberof state-sponsored cyber actors continues to rise alongsidethe severity of cyber attacks, the issue has become evenmore pressing.The renewed vigor with which the European Union (EU) hasseized upon this topic and the arrival of new occupants inthe locus of political authority in the United States presentan opportunity to provide the debate with a more completecontext and to more precisely frame the interests of theplayers involved. This effort sits within the body of work thatframes the construction, sale, and use of OCC as a questionof proliferation.3 Policy efforts should seek to reduce the utilityof these capabilities and influence the incentives of the partiesinvolved in the process of proliferation, rather than seekingvainly to block proliferation entirely.41Adam Segal, “The Code Not Taken: China, the United States, and the Future of Cyber Espionage,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 69, no. 5 (November 27,2015), 0213501344.2Michael P. Fischerkeller and Richard J. Harknett, “Cyber Persistence, Intelligence Contests, and Strategic Competition,” In Policy Roundtable: Cyber Conflictas an Intelligence Contest, eds. Robert Chesney and Max Smeets, (Texas National Security Review, September 17, 2020), -conflict-as-an-intelligence-contest/.3Trey Herr, “Malware Counter-Proliferation and the Wassenaar Arrangement,” Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Cyber Conflict, 2016, https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2711070.4Trey Herr, “Countering the Proliferation of Malware: Targeting the Vulnerability Lifecycle,” The Cyber Security Project, Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Centerfor Science and International Affairs, June 2017, /CounteringProliferationofMalware.pdf; Robert Morgus, MaxSmeets, and Trey Herr, “Countering the Proliferation of Offensive Cyber Techniques,” GCSC Briefings from the Research Advisory Group, 2017, SC-Briefings-from-the-Research-Advisory-Group New-Delhi-2017-161-187.pdf, 161-187.2ATLANTIC COUNCIL

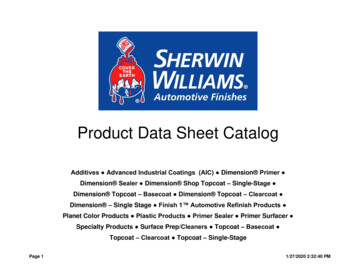

#ACcyberA PRIMER ON THE PROLIFERATION OF OFFENSIVE CYBER CAPABILITIESOFFENSIVE CYBER CAPABILITIES:SEEING THE WHOLE CHAINThe failure of OCC counterproliferation stems from a poorunderstanding of how cyber capabilities are createdand spread. The majority of contemporary policy efforts,including the Wassenaar Arrangement, are meager transplantsof Cold War–era nonproliferation strategies into cyberspace.These efforts, while part of an existing toolkit to counterproliferation efforts, frame OCC as tools and work to block theirsale through export control rules; there are myriad critiques ofthis approach.5 The Wassenaar Arrangement accounted forsome of this, controlling not the malware itself (which it hasdubbed “intrusion software”) but software that was designedfor command-and-control finalities.However, offensive cyber capabilities consist of morethan just malware and its command and control. Stuxnetwas malware attributed to Israel and the United States,6 aworm that did not rely on command-and-control networks.7The malware was designed to target specialized hardware(SCADA systems) adopted to control machinery andindustrial processes, including centrifuges for obtainingnuclear material, and to destroy them by causing controlledmalfunctions, ultimately slowing down the Iranian nuclearprogram.8 Not only was the malware incredibly tailored tothe specific hardware in Iran’s Natanz nuclear site, but themalware itself also used five 0day-exploits,9 was regularlyupdated by malware developers, and likely requiredheavy collaboration between Israeli and US intelligencecounterparts to deploy. The malware delivery mechanism,testing processes, and deployment of the Stuxnet malwarethrough Operation Olympic Games were the culminationof multiple offensive cyber capabilities much broader thanjust command and control. To accurately frame OCC, it istherefore crucial to be able to distinguish and separatedifferent offensive capabilities—to understand OCC as achain of commodities, skills, and activities, moving away froma singular emphasis on malware components and toward thelife cycle of a cyber operation.In this document, we introduce five pillars of offensive cybercapability as a means to characterize the technical andoperational foundations of OCC. The five pillars are vulnerabilityresearch and exploit development, malware payloaddevelopment, technical command and control, operationalmanagement, and training and support. Table 1 provides anoverview of these pillars.The next sections develop a more detailed picture of themarkets in which these transactions take place and describethe five pillars of this chain of OCC.5Gozde Berkil, “Cybersecurity and Export Controls,” The Fletcher School, Center for Law and International Governance, December 10, 2018, ity-and-export-controls/; Dorothy Denning, “Reflections on Cyberweapons Controls,” Computer Security Journal 16, no. 4 (2000):43-53, ections on Cyberweapons Controls.pdf; “Export Controls,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, accessedJanuary 19, 2021, https://www.eff.org/issues/export-controls; Sergey Bratus, DJ Capelis, Michael Locasto, and Anna Shubina, “Why Wassenaar Arrangement’sDefinitions of Intrusion Software and Controlled Items Put Security Research and Defense at Risk—and How to Fix It,” Dartmouth College, October 9, 2014,https://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/ sergey/wassenaar/wassenaar-public-comment.pdf; Sergey Bratus, “The Wassenaar Arrangement’s Intent Fallacy,” Bureauof Industry and Security, US Department of Commerce, December 8, 2015, 20-wa-intent-fallacy-bratuscomments/file; Thomas Dullien, Vincenzo Iozzo, and Mara Tam, “Surveillance, Software, Security, and Export Controls: Reflections and Recommendations forthe Wassenaar Arrangement Licensing and Enforcement Officers Meeting,” Bureau of Industry and Security, US Department of Commerce, February 10, controls-mara-tam/file; Mailyn Fidler, “Proposed U.S. ExportControls: Implications for Zero-Day Vulnerabilities and Exploits,” Lawfare, June 10, 2015, loits.6David Kushner, “The Real Story of Stuxnet: How Kaspersky Lab Tracked Down the Malware that Stymied Iran’s Nuclear-Fuel Enrichment Program, IEEESpectrum, February 26, 2013, l-story-of-stuxnet; Nate Anderson, “Confirmed: US and Israel Created Stuxnet,Lost Control of f-it/; “What Is Stuxnet?” McAfee, accessed January 28, hner, “The Real Story of Stuxnet.”8Ralph Langner, “To Kill a Centrifuge: A Technical Analysis of What Stuxnet’s Creators Tried to Achieve,” The Langner Group, November 2013, /to-kill-a-centrifuge.pdf.9A zero day (or 0day) is a vulnerability that is currently unknown to the software vendor and the organization whose system the vulnerability affects, and forwhich a patch does not exist.3ATLANTIC COUNCIL

#ACcyberAPRIMERON THEOF OFFENSIVECYBERCAPABILITIESTABLE1. THEFIVEPROLIFERATIONPILLARS OF S examplesVULNERABILITYRESEARCHAND EXPLOITDEVELOPMENTDiscoveredvulnerabilities, ordisclosure programsthat facilitate theproliferation ofdiscovered vulnerabilitiesand written exploitsChinese intelligencecommunity vulnerabilityresearch andexploitation, specificallywithin the MSS and itsassociated CNNVDExploit kits sold onunderground forumsBug O Group’s use of aWhatsApp 0dayMALWAREPAYLOADDEVELOPMENTAny malware or toolwritten or used byattackers to conductoffensive cyberoperations, or anyforum that encouragesor conducts exchangeof malwareCustom malwaredeveloped by stateteams that is reverseengineered andpublished by malwareanalystsCommercial malwaremarketRed-team toolsdeveloped and soldthrough commercialofferings andcompanies; postingmalware for researchon GitHubNSO Group’sPegasus spywareTECHNICALCOMMAND ANDCONTROLTechnologies aimed atsupporting offensivecyber operations,e.g., bulletproofhosting, domain nameregistration, server sidecommand-and-controlsoftware, VPN services,or delivery accountsinvolved with the initialcreation of an offensivecyber operationIPs and domainsattributed to stateoperations by threatintelligence reportsBulletproof hostingand other pre-bulletcommand-andcontrol infrastructureTest servers builtto send phishingtests against one’sown companies,infrastructure usedfor penetrationtesting servicesInfrastructure usedby Appin Security forOperation strategic organizationof resources andteams, initial targetingdecisions, and otherfunctions that arerequired to effectivelymanage an organizationthat conducts cyberoperationsChain of commandwithin and organizationof governmentintelligence agenciesCriminal outsourcing,ransomware affiliateprogramsDelegation of dutieswithin a red-teamexercise; escalationpolicies during anincidentGood HarborConsulting’sorganizationalmanagement ofUAE DREAD cybercapabilitiesTRAINING ANDSUPPORTTraining or educationprovided on theoffensive cyberoperation process,expanding the numberof trained professionalsand creatingconnections betweenthem that facilitate thegrowth of OCCNSA’s NationalCryptologic Schoolor other governmentsponsored cybertraining programFraud tutorials,phishing kits,customer supportprovided withinforumsKali Linux tutorialson YouTube,cyber securitycertifications,conference trainingsand talksDarkMatter trainingprovided to UAEcyber operatorsNote: Abbreviations: MSS: China’s Ministry of State Security; CNNVD: China’s National Vulnerability Database; AaaS: Access-as-a-Service; VPN: virtual privatenetwork; IP: Internet Protocol; OCC: offensive cyber capabilities; UAE: United Arab Emirates; DREAD: the UAE’s Development Research Exploitation and AnalysisDepartment; NSA: US National Security Agency.4ATLANTIC COUNCIL

#ACcyberA PRIMER ON THE PROLIFERATION OF OFFENSIVE CYBER CAPABILITIESSEMI- AND SELF-REGULATED MARKETS FOROCC PROLIFERATIONProviders and developers of OCC can be roughly separatedinto self-regulated and semi-regulated spaces. Both spacesprovide access to technology such as malware, supportinginfrastructures, and vulnerabilities, but differ in their maturities,capacities to innovate, and quality of offerings. Self-regulatedspaces operate autonomously, typically through undergroundinternet markets that govern transactions and rules to enforcecontracts. Among the most well-known, 0day.today operates inthe clearweb and is branded as a marketplace specialized invulnerability exploits and 0days (albeit of dubious quality), whileexploit.in and dark0de operate(d) in the underground as wellregulated forums offering their members a trusted environmentto facilitate trade of different products. By contrast, operatorsin semi-regulated spaces typically act in the open, under thejurisdiction of the state where they operate; among them, thenotorious Israeli firm NSO Group states on its website that itprovides “authorized governments with technology that helpsthem combat terror and crime.”10 Both spaces contain actorsof varying capabilities, communities, and resources to developand conduct their own operations. For example, 0day.todayprovides a loosely regulated environment with little assurancethat the exploits therein are effective and undetectable; bycontrast, more strongly (self-) regulated markets like exploit.in,operating in the mainly Russian underground space, providestronger regulation mechanisms aimed at pushing upward theaverage quality of traded products. Services also vary widelyin offered capabilities. These range from supplying individualcomponents to independently developing and conductingwhole offensive cyber operations. The accompanying report,Countering Cyber Proliferation, provides a breakdown overthree case studies of AaaS players of varying capabilitiesacross the proposed five pillars.Actors present within self- and semi-regulated spaces canfurther be divided into government, criminal, and privateactors enabling Access-as-a-Service (AaaS)—i.e., hack-forhire actors effectively selling computer network intrusionservices to clients. A single cyber operation, depending on thecountry of origin and nature of attack, can consist of individualsspanning multiple categories (e.g., government and contractingbusinesses, government and criminal, business and criminal).In the self-regulated criminal space, heterogeneousunderground markets proliferate, ranging from free marketsthat can be easily and freely accessed by any (wannabe)attackers, pull-in markets that enable some mechanisms ofaccess regulation via invite from trusted members of themarket, to segregated marketplaces frequented by highlyskilled cybercriminals.11,12 This progression reflects not onlymore controlled environments, but also access to moremature and innovative attack capabilities (e.g., in the formof new vulnerabilities, malware, or command-and-controlinfrastructure).13Similarly, operators in the semi-regulated space also vary interms of offensive capabilities: from governmental agencieswith ample and mature cyber capabilities, able to develop theirown attacks and capable of autonomously conducting offensivecyber operations at all levels, to private companies offeringlegitimate versions of cyber tools with the same capabilities asthose that may be misused by criminals. Among these, AaaSorganizations also operate in the semi-regulated space, but aredifferent from all other forms of proliferation in that they offerfully fledged offensive services commercially accessible onlyby accredited actors (e.g., governmental agencies with plentifulresources but little or insufficient internal know-how). Theseactors offer and develop advanced offensive capabilities togovernments due to the prices or funding they are able toreceive for providing such services, and their frequent abilityto simultaneously conduct research and development, trainpersonnel, and scale businesses.AaaS groups are known to provide support to governments thatneed established capabilities, but are incapable of producingthem organically. NSO Group is one of the most prominentsuch vendors, providing services to operations in forty-fivecountries.14 The main differences in terms of capabilities thatdistinguish governments from private actors emerge from thepresence of a business model for the latter, which ultimately10“Home,” NSO Group, accessed January 28, 2021, https://www.nsogroup.com/; This claim is largely disputed due to the use of their products to conduct attacksagainst human rights activists and journalists in various countries: Bill Marczak, John Scott-Railton, Sarah McKune, Bahr Abdul Razzak, and Ron Deibert, “Hideand Seek: Tracking NSO Group’s Pegasus Spyware to Operations in 45 Countries,” The Citizen Lab, September 18, 2018, ountries/.11Brian Krebs, “Why Were the Russians So Set against This Hacker Being Extradited?” Krebs on Security, November 18, 2019, d/.12Luca Allodi, M. Corradin, and F. Massacci, “Then and Now: On the Maturity of the Cybercrime Markets, the Lesson that Black-Hat Marketeers Learned,” IEEETransactions on Emerging Topics in Computing, 2016.13Ibid.14Marczak et al., “Hide and Seek.”5ATLANTIC COUNCIL

#ACcyberA PRIMER ON THE PROLIFERATION OF OFFENSIVE CYBER CAPABILITIESneed to remain profitable to operate—a constraint notnecessarily as strong for nation states that have developedadvanced cyber capabilities. While governments may developOCC for strategic reasons, AaaS private groups must achieveeconomic sustainability to continue operations. Nonetheless,Access-as-a-Service firms offer government-level capabilitiesat private sector speeds.operations observed “in the wild.” The differences betweencriminal, government, industry, and AaaS organizationsthat proliferate these capabilities are explained in the nextsection. Table 2 provides a bird’s eye view of the landscapeacross these presented dimensions. Overall, there is aclear progression in offensive capabilities as one movesfrom the underground markets to private and governmentalplayers; on the other hand, some similarities emerge. In thefollowing pages we provide an in-depth view of the specificcapabilities developed across the defined pillars by actorsin the self-regulated and semi-regulated spaces from whichthis overview is derived.The chain of offensive cyber capabilities encompassesfive pillars of activity as laid out below. These pillars arerooted in existing literature and models on cyber operationsand capabilities, as well as in public reporting on cyberTABLE 2: AVAILABILITY OF TECHNOLOGY FOR EACH PHASE ACROSS MARKETPLACESelf-regulated space (Black markets)Semi-regulated spaceFreePrivate - AaaS Pull-inSegregated– – TechnicalCommand andControl– OperationalManagement– VulnerabilityResearchandExploitDevelopmentMalware PayloadDevelopmentTraining andSupportGovernment (*)Notes: Cells indicate the capabilities for a specific pillar for a given actor.Blank cells with a dash – indicate no capabilities for that specific dimension; indicates the actors have only basic capabilities on that dimension, e.g., obtained by operating automated frameworks; indicates actors can repurpose and modify existing technologies in that dimension, e.g., to obfuscate known malware/exploit code; indicates actors can generate novel methods or efforts in that dimension, e.g., 0day exploits.(*) Assessment for governments with mature cyber capabilities. AaaS stands for Access-as-a-Service.6ATLANTIC COUNCIL

#ACcyberA PRIMER ON THE PROLIFERATION OF OFFENSIVE CYBER CAPABILITIESTHE FIVE PILLARS OF OFFENSIVE CYBER CAPABILITY PROLIFERATIONPILLAR ONE:Vulnerability Research and Exploit DevelopmentAttackers find vulnerabilities and write exploitsto gain a foothold in or access to a targetprogram or device, usually within thecontext of a multistage operation.This pillar includes research to findthe vulnerabilities themselves, as wellas disclosure programs and researchorganizations that facilitate the proliferationof discovered vulnerabilities and written exploits.A vulnerability is a flaw in a system’s design, implementation, oroperation and management that could be exploited to violatethe system’s security policy, usually by catalyzing unexpectedbehavior.15 The specific code used to trigger the unexpectedbehavior by using the vulnerability is called an exploit.16 Anexploit is written for a specific vulnerability and the type ofsystem the vulnerability targets.Exploiting a vulnerability provides attackers with access toa target system before installing a malware payload thatcreates the intended final effect. This access becomesespecially effective when so-called zero day vulnerabilitiesare involved. A zero day (or 0day) is a vulnerability thatis currently unknown to the software vendor and theorganization whose system the vulnerability affects, andfor which a patch does not exist. Because of this, a wellengineered exploit for that vulnerability will have no defense15“Internet Security Glossary, Version 2,” IETF Trust, 2007, lity,” F-Secure, accessed January 19, 2021, ility.shtml.7ATLANTIC COUNCIL

#ACcyberA PRIMER ON THE PROLIFERATION OF OFFENSIVE CYBER CAPABILITIESuntil a fix is developed.17 A number of campaigns attributed tonation states employ zero days:18 Cyber operations allegedto originate from North Korea,19 China,20 Iran,21 the UnitedArab Emirates (UAE),22 South Korea,23 the United States,24and multiple other countries25 used zero days to increasetheir access to a target network, download additionalmalware, or install backdoors onto victim computers.Because zero days can provide unmatched access whenconducting offensive cyber operations, vulnerability researchor bug bounty programs are sometimes linked to governmentorganizations to funnel vulnerabilities into state-backed cyberoperations. The US Vulnerabilities Equities Process determineswhether zero day vulnerabilities are disclosed to the public orwithheld for cyber operations on a case-by-case basis.26 Asanother example, CNITSEC, an office within China’s Ministry ofState Security, has operated a Source Code Review Lab outof Beijing since 2003.27 China’s Ministry of State Security hasrepeatedly been associated with Chinese-backed advancedpersistent threats, or APTs, which have conducted cyberoperations against US targets.28Vulnerability disclosure can be similarly affected bygovernment organizations conducting offensive cyberoperations to prevent patching of targeted systems. China’sNational Vulnerability Database (CNNVD) is run by CNITSEC.By comparing publication dates of vulnerabilities within theCNNVD and its US counterpart, the National VulnerabilityDatabase (NVD), researchers found that CNNVD beat NVD topublication for 43 percent of all vulnerabilities, except wherevulnerabilities were used by Chinese APTs29 (after that reportwas released, the CNNVD retroactively altered the publicationdate of the vulnerabilities in question).30 Vulnerability researchalso has legitimate uses for defense within both governmentsand private companies: By finding vulnerabilities in one’s ownsystem prior to exploitation, an organization can update itssoftware, protecting users. Corporate and government-widebug bounty programs are designed for exactly this purpose,effectively “crowdsourcing” security testing.31States and large criminal groups will also use exploits evenafter their vulnerabilities have been patched (known as N-days).While generally less effective, these exploits make up a bulk of17A. Ozment, “The Likelihood of Vulnerability Rediscovery and the Social Utility of Vulnerability Hunting,” WEIS, June 2005.18Maddie Stone, “Reversing the Root: Identifying the Exploited Vulnerability in 0-Days Used in-the-Wild,” Black Hat USA, August 5, 2020, 8.19“North Korean Hackers Allegedly Exploit Adobe Flash Player Vulnerability (CVE-2018-4878) against South Korean Targets,” Trend Micro, February 2, ility-cve2018-4878-against-south-korean-targets.20 Catalin Cimpanu, “Two Trend Micro Zero-Days Exploited in the Wild by Hackers,” ZDNet, March 17, 2020, days-exploited-in-the-wild-by-hackers/.21Ionut Arghire, “Iranian Hackers Exploit Recent Office 0-Day in Attacks: Report,” Security Week, May 1, 2017, t-recent-office-0-day-attacks-report.22 Kathleen Metrick, Parnian Najafi, and Jared Semrau, “Zero-Day Exploitation Increasingly Demonstrates Access to Money, Rather than Skill — Intelligence forVulnerability Management, Part One,” FireEye, April 6, 2020, ey-not-skill.html.23 Eduard Kovacs, “South Korea–Linked Hackers Targeted Chinese Government via VPN Zero-Day,” Security Week, April 6, 2020, ckers-targeted-chinese-government-vpn-zero-day.24 Nicole Perloth and Scott Shane, “In Balitmore and Beyond, a Stolen N.S.A. Tool Wreaks Havoc,” New York Times, May 25, 2019, tool-baltimore.html.25 Metrick et al., “Zero-Day Exploitation Increasingly Demonstrates Access to Money.”26 White House, “Vulnerabilities Equities Policy and Process for the United States Government,” US Government, November 15, 2017, rter%20FINAL.PDF.27“China Information Technology Security Certification Center Source Code Review Lab Opened,” Microsoft News, September 26, 2003, rce-code-review-lab-opened/.28 “Two Chinese Hackers Associated with the Ministry of State Security Charged with Global Computer Intrusion Campaigns Targeting Intellectual Property andConfidential Business Information,” US Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs, December 20, 2018, computer-intrusion.29 Priscilla Moriuchi and Bill Ladd, “China’s Ministry of State Security Likely Influences National Network Vulnerability Publications,” Recorded Future, November 16,2017, bility-influence/.30 Priscilla Moriuchi

This primer reframes the narrative of cyber capability proliferation to be more in line with the life cycle of cyber operations as a whole, presenting five pillars of offensive cyber capability: vulnerability research and exploit development, malware payload generation, technical command and control, operational management, and training and .