Transcription

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/acceptedfor publication in the following source:Mcphail-Bell, Karen(2014)Deadly Choices: better ways of doing health promotion.Croakey: The Crikey Health Blog, 2014.[Article]This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/76238/c Consult author(s) regarding copyright mattersThis work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under aCreative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use andthat permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the document is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then referto the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe thatthis work infringes copyright please provide details by email to qut.copyright@qut.edu.auNotice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record(i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Submitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) canbe identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appearance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source.http:// blogs.crikey.com.au/ croakey/ 2014/ 09/ otion/

Croakey Blog – 14 September 2014Deadly Choices: Better ways of doing health h-promotion/Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the author and do notnecessarily reflect the views and opinions of the Institute for Urban Indigenous Health or itsstaff and member services. The author is a PhD candidate and not employed by IUIH.Health promotion has failed Indigenous Australians1. Australia is a world leader in healthpromotion, ranking highly for life expectancy and health expenditure per person. However,Indigenous Australians continue to suffer grossly disproportionate rates of disadvantageagainst all measures of socio-economic status, including health (ABS, 2013; AIHW, 2011a,2011b)2,3.The concern here is not the concept of health promotion; nor is this an attack on the manypractitioners who work hard to achieve health for all. Rather, issue is taken with theinstitution of health promotion and its application, which has often fallen short of effectingchange for Indigenous Australians.Mainstream health promotion has been unable to effectively engage with the social, culturaland political context of Indigenous Australians. We often see instead a preoccupation withindividual risk factors, such as the holy trinity of substance use, nutrition and physicalactivity, and their associated behavioural and lifestyle interventions (Baum & Fisher, 2014;Porter, 2006; Raphael, 2006)4,5,6.1I use the term Indigenous Australians to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Iacknowledge that the term Indigenous has been co-opted politically by descendants of settlers and that growingdebate surrounds the term (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2009). However, this research has furtherreaching implications than Australia, and draws on knowledge beyond Australia. Therefore I use the term“Indigenous” – carefully, aware of its limitations and hopeful that I have achieved a respectful use of ournals.org/content/22/1/72.full1

Shaped by this fixation, a mainstream health narrative exists, promoting how to live better,healthier lives. Critiques of the foundations of health promotion practice have challenged this(Bond, 2007; McPhail-Bell, Fredericks, & Brough, 2013)7,8, with concern that Indigenouspeople who ‘fail’ to uptake and practice the healthy lifestyle message are further stigmatised(Bond, Brough, Spurling, & Hayman, 2012; Sherwood & Edwards, 2006)9,10. Moreover,debatably, little political will exists for learning from Indigenous people and communities(Cox, 2014; NACCHO, 2014a)11,12.New strengths-based ways of practicing health promotion exist, which centre Indigenousknowledge, perspectives and practices. Mainstream health promotion practitioners couldlearn from those who operate at this interface. However, little research exists regarding thispractice, particularly within an urban context13.The Institute for Urban Indigenous Health’s (IUIH)14 Deadly Choices15 initiative provides anexample of a strengths-based approach to health promotion (McPhail-Bell, 2014)16. IUIHrepresents a partnership between local Aboriginal Medical Services and is part of thecommunity controlled health sector – a sector which has reduced unintentional racism,barriers to access to health care, and is progressively improving individual health outcomesfor Aboriginal people (Holland, 2014; NACCHO, 2014b; Panaretto, Wenitong, Button, &Ring, 2014)17,18,19. IUIH’s Deadly Choices initiative is an umbrella for its health e-largest-employer-of-aboriginal-people/13I acknowledge the diversity within and between rural, remote and urban communities. I draw particularattention to the diversity within and between urban communities, which is the context of focus for this study andIUIH’s core ices-leading-wayprimary-care102

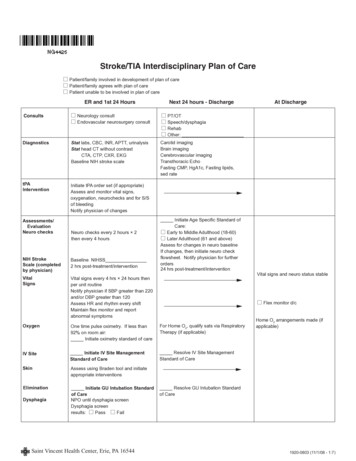

Unlike traditional health promotion typically driven by experts, Deadly Choices employs aunique model of leadership for behaviour change. In this inclusive approach, “everyone canbe a leader” by way of their choices: one leads by the example they set, rather than positionthey hold or message they preach. Leaders are distributed throughout community: as rolemodels, ambassadors, as family, as influencers of change. IUIH’s diverse preventative healthteam also endeavours to be leaders themselves.For Deadly Choices, leadership is culture and culture is relational. This form of leadership isdifferent from Western interpretations of leadership – although also strategically draws onsuch concepts. The expression of leadership shifts according to context and involves standingout, but not too much. Being a leader means making deadly choices: from a healthy lunch, tostudying for a dream job, to looking after each other – in other words, choices across thesocial determinants of health (for example, Figure 1 and Figure 2).Figure 1: One family’s deadly choices involved family time, being active outdoors: “Deadly Choices now Deadly Buraay's for the Future. Could not just choose one as so many of our choices now will affect ourkids in the future” (April 2013).2020https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid 10151522109008022&set o.225245497554520&type 1&ref nf3

Figure 2: A parent shares their son's deadly choice: to get an education (July 2013).21Deadly Choices is based on community-driven concepts of health and engagement.With the question, “What’s your deadly choice?” an ongoing conversation between the healthpractitioners and community, and within community, takes place. Community members shareand promote their deadly choices, thereby co-constructing the brand and concepts of healthunderpinning Deadly Choices.In doing so, Deadly Choices shares power between practitioners and community, contrastingtraditional health promotion approaches dominated by experts advising about healthylifestyle. This is not to say Deadly Choices does not promote a healthy lifestyle agenda butrather that such an agenda is part of a broader approach.Deadly Choices uses fun and innovative engagement strategies, emphasising inclusionand participation.Social media provides a platform for dialogue and interaction, facilitating a sophisticatedconnection point to the community Deadly Choices serves. Deadly Choices merchandise,available only by earning it, enables people to assert their connection to Deadly Choices intangible ways (Figure 3). A range of schools programs, community events, camps and other21https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid 10201522130795105&set o.225245497554520&type 1&ref nf4

programs are also in place, with developing evidence on their effectiveness (Malseed,Nelson, & Ware, 2014; Malseed, Nelson, Ware, Lacey, & Lander, 2014)22,23.Figure 3: A group of community members are awarded their Deadly Choices jerseys for participation ata community event. Jerseys and hoodies have to be earned and hold value in the community (photoprovided by IUIH 2013)Deadly Choices normalises healthy lifestyle in a package of strength, culture and identity.Deadly Choices “do(es) things differently” and draws on a strategic use of healthy lifestyle.In other words, Deadly Choices focuses on the community agenda it serves to include whilenot limited to healthy lifestyle. In doing so, the Deadly Choices leadership model shifts theagenda of health promotion more broadly.Deadly Choices is positive and frames Indigenous identity as health producing (Figure4). Existing leadership is acknowledged and showcased (Figure 5), presenting a counternarrative to the deficit focus of mainstream health promotion practice and narrative. Thenarrative is positive, inclusive and proud, and controlled by Indigenous au/view/journals/dsp journals pip abstract scholar1.cfm?nid 261&pip PY140415

Figure 4: A Deadly Choices ambassador shares the importance of being Aboriginal (November 2013.24Figure 5: Deadly Choices ambassadors (June /556101794468887/?type 089400036792/?type 3&theater6

Indigenous leadership is paving the way for health promotion practice. The lessons fromDeadly Choices consequently have relevance to all health promotion practice – not onlyIndigenous health promotion.AcknowledgementI acknowledge and thank the wisdom, sympathy and encouragement of: IUIH including IanLacey and Alison Nelson; my supervisors, Associate Professor Mark Brough, Dr ChelseaBond and Professor Bronwyn Fredericks; and the numerous participants involved in my PhDresearch. All of you inspire me and continue to influence me. Thank you.Author contact informationEmail: karenmcphailbell@gmail.comTwitter handle: solomon kazzaMore work: , Karen.html7

ReferencesABS. (2013). 3302.0.55.003 - Life Tables for Aboriginal and Torres Strait IslanderAustralians, 2010-2012 Canberra.AIHW. (2011a). 4704.0 - The Health and Welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres StraitIslander Peoples, Oct 2010. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and /abs@.nsf/lookup/4704.0Chapter755Oct 2010.AIHW. (2011b). Life expectancy and mortality of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanderpeople. Canberra.Australian Human Rights Commission. (2009). National Indigenous Representative Bodyworkshop: Summary report. Stamford Glenelg, Adelaide: Australian Human RightsCommission.Baum, Fran, & Fisher, Matthew. (2014). Why behavioural health promotion endures despiteits failure to reduce health inequities. Sociology of Health & Illness, 36(2), 213-225.doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12112Bond, Chelsea. (2007). "When you're black, the look at you harder" - NarratingAboriginality within Public Health. (Doctor of Philosophy), University ofQueensland, Brisbane.Bond, Chelsea, Brough, Mark, Spurling, Geoffrey, & Hayman, Noel. (2012). ‘It had to be mychoice’ Indigenous smoking cessation and negotiations of risk, resistance i:10.1080/13698575.2012.701274Cox, Eva. (2014). Forrest report ignores what works and why in Indigenous policy.Retrieved from icks, Bronwyn, & Anderson, Margaret. (2013). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islandercookbooks: Promoting Indigenous foodways or reinforcing Western traditions? Paperpresented at the Peer Reviewed Proceedings of the 4th Annual Conference, PopularCulture Association of Australia and New Zealand (PopCAANZ), Brisbane,Australia.Gomes, Tonya, Leon, Alannah, & Brown, Lee. (2013). Indigenous health leadership:Protocols, policy, and practice. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and IndigenousCommunity Health, 11(3).Holland, Christopher. (2014). Close the gap: Progress and priorities 2014. Melbourne: OxfamAustralia.Malseed, Claire, Nelson, Alison, & Ware, Robert. (2014). Evaluation of a school-basedhealth education program for urban Indigenous young people in Australia. Health, 6,587-597.Malseed, Claire, Nelson, Alison, Ware, Robert, Lacey, Ian, & Lander, Keiron. (2014).Deadly Choices community health events: A health promotion initiative for urbanAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Australian Journal of Primary Health,In production.McPhail-Bell, Karen. (2014). We have a lot to learn yet: A postcolonial lens in healthpromotion. Paper presented at the AIATSIS National Indigenous Studies Conference- Breaking Barriers in Indigenous Research and Thinking: 50 Years On, NationalConvention Centre, Canberra. http://eprints.qut.edu.au/69595/8

McPhail-Bell, Karen, Fredericks, Bronwyn, & Brough, Mark. (2013). Beyond the accolades:A postcolonial critique of the foundations of the Ottawa Charter. Global HealthPromotion, 20(2), 22-29. doi: 10.1177/1757975913490427NACCHO. (2014a). NACCHO press release - Andrew Forrest: Aboriginal communitycontrolled health sector is the single largest employer of Aboriginal people:NACCHO.NACCHO. (2014b). NACCHO press release - CTG report: Investment in Aboriginalcommunity controlled health key to closing the gap: NACCHO.Panaretto, Kathryn S, Wenitong, Mark, Button, Selwyn, & Ring, Ian T. (2014). Aboriginalcommunity controlled health services: leading the way in primary care. MedicalJournal of Australia, 200(1), 649-652. doi: 10.5694/mja13.00005Porter, Christine. (2006). Ottawa to Bangkok: Changing health promotion discourse. HealthPromotion International, 22(1), 72-79.Raphael, Dennis. (2006). The social determinants of health: What are the three key roles forhealth promotion? Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 17(3), 167-170.Sherwood, Juanita, & Edwards, Tahnia. (2006). Decolonisation: A critical step for improvingAboriginal health. Contemporary Nurse, 22(2), 178.Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. (2005). On tricky ground: Researching the native in the age ofuncertainty. In N. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of QualitativeResearch (3rd ed., pp. 85-107). Thousand Oakes: Sage Publications.9

individual risk factors, such as the holy trinity of substance use, nutrition and physical activity, and their associated behavioural and lifestyle interventions (Baum & Fisher, 2014; Porter, 2006; Raphael, 2006)4,5,6. 1 I use the term Indigenous Australians to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. I