Transcription

PROPERTYRIGHTS:A PRIMERBUL 834 (Revised)

Support for this project was generously providedby the following organizations:Western Rural Development CenterFarm FoundationMore information on the Western Rural Development Center can be found athttp://extension.usu.edu/WRDC/The purpose of the Western Rural Development Center (WRDC) is to strengthen ruralfamilies, communities, and businesses by facilitating rural development research and extension(outreach) projects cooperatively with universities and communities throughout the West.More information on the Farm Foundation can be found athttp://www.farmfoundation.org/The Farm Foundation focuses its programming on six priority areas: globalization, environmental and natural resource issues, consumer issues, role of agricultural institutions, rural community viability, and new technologies.Technical Editor: Kathleen Painter

Property Rights: A PrimerEdited by Neil MeyerTable of Contents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .PageIntroduction to Property Rights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4Neil Meyer, University of IdahoProperty and Property Rights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6Alan Schroeder, The University of WyomingWhy Property Rights? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7Larry Libby, The Ohio State UniversityWhy Property Rights Matter! . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9George McDowell, Virginia Institute of TechnologyProperty Rights In Historical Perspective . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11Jerry L. Anderson, Drake University Law SchoolCommon Property and Natural Resource ManagementRobert Gorman, University of Alaska, Fairbanks. . . .13Economics of Property Rights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17Steve Medema, University of ColoradoState Property: Wildlife, Lands, AndOpen Spaces In Colorado . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20Andrew Seidl, Colorado State UniversityProperty Rights: A Philosophical Perspective . . . . . . . . . . . . .22Paul B. Thompson, Purdue University

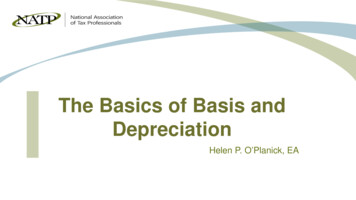

Introduction to PropertyRightsby Neil MeyerDepartment of Agricultural Economics & Rural Sociology, University of IdahoWe all have opinions about propertyrights. Many of us are surprised when wemeet someone with a different point ofview about property rights. Certainlythere is not one, universal view of property rights today.Property actually refers to the rightto a stream of benefits from a given setof resources. In the U.S., access to thosebenefits is controlled in four basic ways:private ownership plus three forms ofpublic ownership—open access, closedaccess, and state.Where do property rights come from?Property rights come from cultureand community. A person living totallyapart from others, on a remote island,for instance, or in the American Westof the early nineteenth century, doesnot need to worry about property rights.When people come together, however,the need for specific arrangements aboutproperty ownership becomes apparent.This group or community then definesand enforces rules of access to the benefits that come from owning land orother property.Who really owns my property?“This land is mine, mine to use andenjoy, mine to treat as I wish,” is a common sentiment among many ownersconcerning their rights to land. This iscalled the “human territorial imperative.” Landowners obviously possessmany rights in the properties they hold,but do they really have all the rightsthey claim? Various actions by governments and courts in recent years suggestthat private owners’ property rights areshared with the public, and that theserights are limited and can change overtime. We are all part of a society thatdefines our rights and has the power toredefine them over time.What are property rights? Property rights establish relationshipsamong participants in any social andeconomic system. “Property” is actually the stream of benefits from a particular resource. The “right” to thatstream of benefits is an expression ofthe relative power of the bearer.Ownership of a property right com-4Property Rights: A Primermands certain responses from otherpeople that are enforced by the government and culture.Producers who own a hundred acresof cropland are entitled to the returnsfrom their property, managementskills, and good sense. They are protected from trespass by their neighborsand by agents of the state. The production from their land, or stream ofbenefits, is theirs to sell or give awayas they see fit. Property rights are a function of whatothers are willing to acknowledge. Aproperty owner’s actions are limitedby the expectations and rights ofother people, as formally sanctionedand sustained in law.The boundary between an obligationand a right varies. Patterns of rightsand obligations reflect prevailingjudgments about fairness, based onpeople’s values. Government has theoverall responsibility to protect publichealth and safety, and to promotegeneral welfare through selectiveexercise of discretion that sustainsquality of life (Libby, 1994, p. 1000). Property rights can be likened to abundle of sticks, with each stick representing a right, or a stream of benefits(Fig. 1). The bundle expands as sticksare added and it contracts as they aretaken away. Important sticks, forexample, may be the right to sell, tomortgage, to subdivide, to lease, andto grant easements.The culture or community thatgrants the rights also reserves a numberof sticks for its own use. The most common rights reserved by the communityas a whole are the right to tax, the rightto claim property for public use, theright to control the type of private use,and the right to dispose of the propertyin case of death. More recently, issuessuch as water quality protection, speciespreservation, and even the preservationof visual landscape have also been withdrawn from the individual owner’s property rights bundle.Governments, acting for the publicand for society as a whole, have longexercised the power to tax private properties. They also have the time-honoredright to take property for public useunder eminent domain, with just compensation. Police powers can be used inmaking and enforcing regulations thataffect owners and their use of land(Barlowe, R., 1990, Southern RuralDevelopment Center).In addition to the formal rights ofgovernment, communities can use otherpowers to influence private propertyowners. These other powers includepublic spending, public ownershippower, and public opinion.History shows that concepts of property that were accepted in the pastchange with new conditions and thepassing of time. Early communitiestreated land and other natural resourcesas a communal resource held in jointownership. Under feudalism, every person’s status in society was directly related to the rights that person held inland. The distribution of those rightsdiffered greatly from the ones we havetoday, but they are important becausethey provide the basis for our presentconcept of property rights.How are property rights defined?Five legal terms come down to usfrom the feudal era. These terms—property, fee, estate, interest, and right—have similar meanings and can generallybe used as substitutes for each other.“Fee simple” ownership signifies thatthe owner enjoys all the rights one canhold in property.Many citizens still cherish the individualistic views that were popular onthe American Frontier. However, reviewof the many programs adopted by local,state, and federal governments in recentdecades indicates that, as a society, wehave moved towards acceptance of alarger role for government. The reasonsfor this change over the past 200 yearsinclude increasing population, risingincomes and standards of living, morecompetition for available resources, rising literacy rates, wider suffrage (womenand minorities have the right to vote),and conservation and environmentalconcerns.From a historical point of view, itappears that the rights we hold in property spring from society. Individuals maybelieve that their rights are God-givenor endowed by natural law, but in practice, the nature of one’s rights dependsupon the interpretations accepted bythe society in which we live. Rights arereal only when the sovereign power orgovernment, which acts as the agent ofsociety, recognizes them and is willing todefend and enforce them.Subtractions from fee simple owner-

ship do not necessarily mean that property has less value, or that it providesfewer satisfactions to its owners.Residential easements that deliver powerand water while putting utility underground usually enhance property values.The same can be said for covenants andzoning rules that protect landscapeviews, control noise levels, or affectarchitecture. More recently, the right topollute air and water has been takenaway from individual owners.Why are property rights important?Because property rights are culturallydefined and enforced and because different groups gain and lose power, no onecan be certain how far the currentmovement will go to broaden publicpowers over private property. The interests of different groups vary greatly.Those seeing private ownership as anopportunity for making money andacquiring wealth have obvious reasonsfor trying to stop or reverse the trendtoward more public power. Others, whoview land as a scarce and fragileresource, the use of which is closelyintertwined with community concerns,argue for even more public supervision.Most Americans’ attitudes lie betweenthese two points.With the prospect of strongerdemands and pressures for public programs to direct land use, individualowners may very well fear that attitudechanges will strip them of certain rights.A growing sentiment for wideracceptance of a public trust view ofrights calls for recognition that therights enjoyed by owners of privateproperty are balanced by their responsibilities. It is to society’s advantage thatowners use land for productive purposes.Owners have the responsibility to useland, or other streams of benefits, inways that do not cause injury or loss ofbenefits to others or work against thebasic interests of others in the community.What is common property?Common property is joint ownershipof a stream of benefits. Management ofcommon property cases is more complicated and often becomes controversialbecause groups and individuals have different values and opinions about how tomanage a given resource. Many propertyrights conflicts today concern management of commonly owned resources.with the concept of private property.Other types of property regimes includeopen access, communal, and state orgovernmental.Open access property has no governance, and everyone can use and takepart of the benefit stream. This situationof uncontrolled use often results in deterioration of the resource. Fishing on theopen seas is an example of this management regime.Communal management of propertymeans it is jointly owned but there arelimits to access and use of the benefitstream. Those who jointly own theresource exercise control over use of thebenefit stream. Many New England lobster fisheries are managed in this manner.Governmental managers make decisions and rules for access and use of benefit streams to state-owned property.Rules for use and allocation of the benefits from publicly owned property oftenbecome controversial, for example, grazing and logging on public lands in thewestern U.S. The same is true for public parks in all areas of the U.S.Final points Property is a benefit that a society anda culture agree to protect. A property right is a claim to the benefits or stream of benefits derivedfrom the property.References:Barlow, Raleigh. 1990. Who Owns YourLand? Southern Rural DevelopmentCenter, Mississippi State University,Starkville.Libby, Lawrence W. 1994. Conflict onthe Commons: Natural resourceentitlements, the public interest, andagricultural economics. AmericanJournal of Agricultural Economics,76(5):997-1009.Table 1. Characteristics of different property rightsType of propertyPrivatePublicOpen accessClosed idualAccessClosedEnforcementSociety/LawAll membersGroup membersGovernmentNo oneGroup membersGovernmentAll membersGroup membersAllNo oneGroup membersGovernmentFigure 1. Bundle of property rightsTheBundleof ofRightsin inLandTheBundleRightsLandPublic RightsLandowner RightsTaxSellLeasegeortgaTake For Public UseMSubdivideControl Use OfeDevisEscheatGrant EasementsWhat are the different types ofcommon property?Ownership and management areoften confused when the term commonproperty is used. Everyone is familiarProperty Rights: A Primer5

Property and PropertyRightsAlan Schroeder, Associate ProfessorDepartment of Agricultural Economics, The University of WyomingIntroductionStories of property rights conflicts areregularly on the front page of localnewspapers—landowners criticizing thegovernment for excessive regulations;neighbors complaining about environmental or health problems created byadjoining land uses; environmentalistand others berating both governmentand industry for losses of prime agricultural land, wilderness areas, wildlifehabitat, and scenic rivers. In the past,parties have gone to court, seeking alegal ruling that some private propertyright or important public interest wasbeing threatened. The resulting rulingsfrequently satisfied neither the disputants nor the public in general.In the western United States, theseconflicts often focus on publicly heldlands. Federal lands represent more thanforty percent of land ownership inAlaska, Arizona, California, Oregon,Idaho, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming.Mining, forestry, grazing, recreation, andenvironmental interests often clashregarding how well publicly-heldresources (e.g., waters, lands, wildlife)are faring, who should participate in themanagement decisions, and what (ifany) private or collective property rightsexist in these resources. Some politicians and social commentators suggestthat these resources might be bettermanaged if legal title was transferredinto private hands (privatization).Others have challenged these contentions.It is easy to dismiss these very publicand sometimes rancorous disputes.These disputes are often clothed inwords and phrases such as “private property rights,” “takings,” “public healthand safety,” “sustainability,” “publictrust” and “protection of future generations.” These terms are often simply dismissed as interest groups manipulatinglanguage in an attempt to capture public opinion for their own purposes. Todo so is a mistake, however, because itseems clear that principles beyond selfinterest motivate many of the disputants. Indeed the expenditures andpersonal risks made by Mr. Hedge andothers participating in the sagebrushrebellion in the West seem to only6Property Rights: A Primermake sense if we accept the premisethat they are motivated by principlesother than or in addition to self-interest, narrowly defined. The same can besaid about many agency, environmental,and industry representatives. We willexplore this point in even greater detailin subsequent papers.It is probably more accurate to saythat many of these disputes turn on fundamental confusion regarding threethings: 1) what principles should motivate government policy regarding natural resources; 2) what property rightsexist in disputed resources; and 3) howeffective are different private and publicproperty management systems inachieving these ends.First, even professionals disagree onthe content and meaning of specifictypes of property rights. For example,some economists refer to resources, notsubject to any ownership or control, as“common property;” others call thesame things “open access” resources anduse the term “common propertyresource” to refer to property that isjointly owned and/or managed by morethan one person or organization.Second, interest group members donot necessarily agree among themselveson the principles or solutions thatshould be applied in particular disputes.Books and articles discussing publiclands and the sagebrush rebellion pointout that some permittees and policymakers favored privatizing publicly-heldlands, claiming such a move wouldmaximize public welfare. Others favoredprivatization, not because of its socialwelfare impact but rather because itwould formally recognize what they sawas “rights” already held by the user (arights-based justification). In the end,Secretary Watts rejected privatizationand adopted a “good neighbor policy”under which title was retained by thefederal government but greater management control was transferred to permittees. Commentators suggest this policywas justified using both efficiency andrights-based principles.Third, as we indicated above, disputants often make broad generalizations—both favorable and unfavorable—regarding the effectiveness ofpublic and private management of natural resources. A better understanding ofthe effectiveness of particular propertyand management regimes might go along way in resolving some of these disputes.The objective of this series of papersis to facilitate public dialogue by identifying and clarifying the underlyingterms, principles, and positions readersmay encounter in the current naturalresource and property debate.Whenever possible, readers will be presented with research exploring the effectiveness of particular property and management regimes in dealing with specificresources. Though some claims may beshown to be unsupported by currentdata or legal reasoning, our primary purpose is not to act as judges.This series is organized in the following fashion. In this, the first paper, wewill briefly describe some the principlesand terms found in the current propertydebate. In the remaining papers thewriters will illustrate how these principles and terms can be used to understand and critically examine public policy debates in such areas as: Property rights and land use planning Property rights and environmentallaw Property rights and public lands Property rights and aboriginal landsThere are some limitations to ourapproach. We believe establishing acommon vocabulary is crucial to facilitate dialogue. Nevertheless, as we indicated above, there is no common agreement among professionals. Readersshould be aware of this fact whenreviewing the bibliography. We mustalso reiterate that we will draw no conclusions regarding which propertyregime or management system is best.Our primary purpose is to facilitateunderstanding, not act as judges.Moreover, many of our statements willbe generalizations. In a series of shortpapers it is impossible to fully summarizethe rich and varied backgrounds andprinciples underlying each interestgroup’s position. We hope the bibliography attached to each paper will allowreaders to delve more deeply into theconflicting views.Recognizing these problems, we askreaders to suspend judgment until eachargument is presented. In this way readers can better understand what motivates those with whom they might agreeor disagree. Sometimes a conclusionthat an opponent’s argument “does notmake sense” may simply mean we areusing a different measure of “sense” thanthey. We also ask readers to think

about other possible principles, arguments, and solutions we may havemissed in our brief summaries. In doingso, readers may find mutually acceptablesolutions to similar problems in theircommunity.Illustrating the language of “property”and “property rights” conflictsIn a famous early American case,Pierson v. Post, 3 Gaine 175 (N.Y.1805), the plaintiff, Post, claimed:“[B]eing in possession of certain dogsand hounds under his command, did,‘upon a certain wild, and uninhabited,unpossessed and wasteland, called thebeach, find and start one of those noxious beings called a fox,’ and whilstthere hunting, chasing and pursuing thesame with his dogs and hounds, andwhen in view thereof, Pierson, wellknowing the fox was so hunted and pursued, did in the sight of Post, to preventhis catching the same, kill and carry itoff.” Post sued Pierson, claiming a property right in the fox. How should thecourt have ruled?Definitions of “property” and“property rights”Black’s Law Dictionary defines property as: “That which is peculiar or proper to one person; that which belongsexclusively to one. In a strict legalsense, an aggregate of rights which areguaranteed and protected by government.”Similarly, Webster’s Ninth NewCollegiate Dictionary provides us with afew definitions: “property.2a: something owned or possessed, specif.: apiece of real estate; b: the exclusiveright to possess, enjoy, and dispose of athing: OWNERSHIP; c: something towhich a person has a legal title; d: one(as a performer) under contract whosework is esp. valuable.” and“property right a legal right orinterest in or against specific property.”The terms “property” and “propertyrights” under these definitions refer notto a “thing”—the fox in the aboveexample—but rather to the real relationship among people regarding thething. Thus the issue in Post is “DidPost have a right enforceable by a courtto take the fox and did Pierson have anequivalent duty to not interfere withPost’s hunting?”What does it mean when we say a person has “property rights”?Legal and economic commentatorsfrequently indicate that property consists not of a singIe right but rather—asthe definitions above suggest—an aggregation or bundle of rights.Unfortunately, the same commentatorsoften mean different things when theyrefer to this bundle of rights.The property estate: the “bundle ofrights” as a special conceptThe term “bundle of rights” is sometimes used in a special or physical sense,particularly when referring to real property. For example, different persons mayhave legal title to the mineral, air,water, and/or surface rights associatedwith land at a particular location. Thatis, a property “owner” may have a rightto build on or cultivate the land (thesurface estate) but not to remove itsrock, oil and gas, or coal without firstobtaining permission from the mineralestate “owner.”This same special concept can beemployed in other contexts. For example, the court in Post held that Postwould have a “property right” in the foxif he had physical custody of it.Similarly, some states have held that aproperty right attaches to oil and gas,water, and other movable (sometimescalled “fugitive”) resources when theyare in possession of a particular party.The ownership interestRecently some commentators havesought to separate the ownership interest into its component parts. For example, McCay divides ownership interestinto two parts: Title: Who has legal title to the property. Management: Who determines howthe property may be used.McCay is not entirely clear as towhat particular rights are contained ineach of these two categories. For example, we might further subdivide the“title interest” (our label) into the rightsto exclude others, use or receive benefitsfrom its use, and/or transfer legal title toanother.ReferencesMcCay, Bonnie. 1996. Forms of property rights and the impact of changingownership. Increasing Understanding ofPublic Problems and Policies,Proceedings, Farm FoundationNational Public Policy EducationConference, Providence, RI, p. 127.Why Property Rights?Larry Libby, C. William Swank Professor of Rural-Urban PolicyThe Ohio State UniversityProperty rights are essential to theexchange process because they definethe opportunities available to peoplewithin an economic system. People mustclearly understand what they are buyingor selling, what the product or service is,and the flow of rights and opportunitiesthat go with a tangible exchange.Property is not the tangible thingbeing bought or sold. What is exchangedis the right to use a stream of benefitsfrom that property or object in someway, and there are always limits to thoserights. You have the right, for example,to slice up a tomato and put it in a sandwich but not to throw the tomato atsomebody with whom you happen todisagree. Similarly, the owner of a pieceof real estate may own the right to dosome things on and with that land, butnot to do other things.While the notion of property rights isessential to transactions in any kind of amarket context, those rights are separateand defined, and they may differ fromone transaction to another.Rights as social agreementA right exists only if you and othersin society, collectively and reinforced bythe state, accept, acknowledge, andagree to its existence. University ofWisconsin agricultural economist DanBromley has said, “Rights are not relationships between me and an object, butbetween me and others with respect tothat object.”Rights to property, then, exist only ina publicly sanctioned context withinthe social system in which there is general acceptance of the right being exercised. Once social acceptance is accomplished, the state reinforces and ensuresthe relationship between ownership andexercise of the associated rights.Without enforcement, rights have verylittle substance and essentially cannotbe exercised.Rights are limited by what you andothers will agree is acceptable. My rightto do something is a function of whatyou’re going to let me get away with,both in a formal sense and in a less formal sense.Property rights are transferableIn order for a market to function,rights to the flow of benefits associatedwith a tangible object must be transferable from one person to another. TheyProperty Rights: A Primer7

may be transferred collectively or separately. Mineral rights may not includesurface rights. Your rights to use wateradjacent to your land are limited by theimpact your actions may have on otherpeople who are also dependent on thatwater.Rights differ according to circumstanceThe property rights movement mostfamiliar to people in the United Statestoday relates to real property (land) andto the flow of services that comes fromland ownership.A landowner has certain exclusiverights that others cannot exercise.These rights are not absolute, however.Members of the general public mayhave interests that impose limits on aproperty owner’s rights. The interest ofnon-owners is reflected in the institutions and policies that evolve aroundthe flow of services, the flow of goods,and the flow of opportunities from apiece of land that are not necessarilylimited to the person who holds theland title.When a property owner’s incomefrom a piece of land is compromised bypublic actions of some kind, for example, by a new law, does the owner havea right to compensation because thegovernment has taken away a land useopportunity? Or is the governmentreclaiming rights that were granted tothe owner when demand for land services were different?Range policy in the western UnitedStates is a good example of these questions. Rights in range land were grantedat a time when it was clearly in the public interest for private individuals toinvest in and operate those resources forthe income generated by raising beef orwool. More recently, there is interest inresource services other than the commodity values associated with cattle orsheep. Government is saying, “We’regoing to take back from you the rightthat we gave you years ago.”Debates over “the public interest”frequently call for a reallocation, or arethinking of the distribution of rightsin real property. Whether a change ofproperty rights is a cost or a benefit really depends on one’s point of view andthe existing allocation of propertyrights.Two basic lines of argument exist onthis question. First is the natural rightstheory, which asserts that ownershiparises from the natural order of thingsand is not subject to the whims of government. That is, land becomes property through the effort of an individual tomake that land generate income and8Property Rights: A Primerproduce something of monetary value.According to this argument, the ownerhas an inherent right to that landbecause of the efforts that turned thebasic resource into a flow of services,with value associated to them. This is aprominent theory of property rights inmany current discussions.The second argument regards ownership and property as a social convention, something created by people toaccomplish community purposes.According to this view, property ownership is a function of human institutionsthat establish sets of land services forsociety. No set of rights is natural or permanent. All are relative to prevailingviews about natural resources and landservices that come from those resources.Common propertyRights to property are complicated insome cases by the character of theprocess that creates those rights. WhatGarret Hardin has famously called the“tragedy of the commons,” reallydescribes open access to a set ofresources. There is an important distinction between common propertyresources and open access resources.Hardin overlooks the reality that bothformal and informal rules govern the useof property that is held in common by agroup of like-minded individuals. Theserules encourage stewardship of the landor resource and discourage exploitation.The lobster fishery along the coast ofMaine is one example of common property. A set of formal rules exists aboutthe size of lobsters that can be taken,but the real governance of that lobsterfishery is the informal way that lobsterfishers themselves keep track of eachother.It would be impossible for me, assomeone from “away,” to come toWinter Harbor, Maine, put out a stringof lobster traps, and expect to get anything out of it. I could get the license,but the other lobster fishers in thattown would not take kindly to an interloper; eventually my traps would disappear. My ability to make an incomewould be compromised because I am notpart of the community that is attempting to gain a living from those resources.Within the coastal lobster fishery,people know that their fishing isrestricted to a certain part of the coastline. No one goes from one harbor tothe next. The boat numbers are known,as are the color of the traps. There is astrong, informal system gov

there is not one, universal view of prop-erty rights today. Property actually refers to the right to a stream of benefits from a given set of resources. In the U.S., access to those benefits is controlled in four basic ways: private ownership plus three forms of public ownership—open access, closed access, and state. Where do property rights .