Transcription

Annual Flow ReportREFUGEES AND ASYLEES: 2017MARCH 2019HomelandSecurityOffice of Immigration StatisticsOFFICE OF STRATEGY, POLICY & PLANS

Refugees and Asylees: 2017NADWA MOSSAADINTRODUCTIONThe United States provides refuge to certain persons who have been persecuted or have a well-founded fear ofpersecution through two programs: a refugee program for persons outside the United States and their eligible relatives,and an asylum program for persons in the United States and their eligible relatives. This Office of Immigration Statistics(OIS) Annual Flow Report presents information on persons admitted to the United States as refugees and those who enteredthe U.S. asylum process in 2017.1A total of 53,691 persons2 were admitted to the United Statesas refugees during 2017. The leading countries of nationalityfor refugees admitted during this period were the DemocraticRepublic of the Congo, Iraq, and Syria. An additional 26,568individuals were granted asylum during 2017,3 including16,045 individuals who were granted asylum affirmatively bythe U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS),4 and10,523 individuals who were granted asylum defensively bythe U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). The leading countries ofnationality for persons granted either affirmative or defensiveasylum were China, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Traveldocuments were issued to 3,831 individuals who wereapproved for derivative asylum, allowing their admission tothe United States. In addition to those approved overseas,3,735 individuals were approved for derivative asylum statuswhile residing in the United States.DEFINING “REFUGEE” AND “ASYLUM” STATUSTo be eligible for refugee or asylum status, a principalapplicant must meet the definition of a refugee set forth insection 101(a)(42) of the Immigration and Nationality Act(INA), which states, in part, that a refugee is a person who isunable or unwilling to return to his or her country ofnationality because of persecution or a well-founded fear ofpersecution on account of race, religion, nationality,membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.5Applicants for refugee status are outside the United States,123452In this report, years refer to fiscal years (October 1 to September 30).Refugee data in this report may differ slightly from numbers reported by the Department ofState (DOS). DOS refugee numbers include Amerasians (children born in Cambodia, Korea,Laos, Thailand, or Vietnam after December 31, 1950, and before October 22, 1982, andfathered by a U.S. citizen), whereas the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS)reports Amerasians as lawful permanent residents.These asylum grants were based upon a principal asylum beneficiary’s application, whichmay also include an accompanying spouse and unmarried children under 21 years of age.They do not include individuals who were approved for follow-to-join asylum status whileresiding in the United States or abroad.Affirmative asylum data for fiscal year 2017 were retrieved by the DHS Office of ImmigrationStatistics (OIS) in January 2018. Data in this report may differ slightly from fiscal yearend 2017 numbers retrieved and reported at different times by DHS’s U.S. Citizenship andImmigration Services (USCIS) Asylum Division.Congress expanded this definition in the Illegal Immigration Reform and ImmigrantResponsibility Act of 1996, providing that persons who have been forced to abort apregnancy or undergo involuntary sterilization or who have been persecuted for failure orrefusal to undergo such a procedure or for other resistance to a coercive population controlprogram shall be deemed to have been persecuted on account of political opinion.whereas applicants seeking asylum are either in the UnitedStates or arriving at a U.S. port of entry (POE).To meet the INA’s refugee definition, a person must be outsidetheir country of nationality, unless the person has nonationality, in which case they must be outside of the countryin which they “last habitually resided.”The INA provides the President with the authority to designatecountries whose nationals may be processed for refugee statuswithin their respective countries (referred to as “in-countryprocessing”). In-country processing is also authorized forextraordinary individual protection cases for whichresettlement consideration is requested by a U.S. Ambassadorin any location. In 2017, certain nationals of Iraq, Cuba,Eurasia, and the Baltics were re-designated for in-countryprocessing, as were qualified children from El Salvador,Guatemala, and Honduras through the Central AmericanMinors (CAM) program.6REFUGEESHistory of U.S. Refugee ResettlementThe United States has a long history of refugee resettlement.The Displaced Persons Act of 1948 was passed to address themigration crisis in Europe resulting from World War II,wherein millions of people had been forcibly displaced fromtheir home countries and could not return. By 1952, theUnited States had admitted over 400,000 displaced peopleunder the Act. The United States extended its commitments torefugee resettlement through legislation including the RefugeeRelief Act of 1953 and the Fair Share Refugee Act of 1960. TheUnited States also used the Attorney General’s parole authorityto bring large groups of persons into the country forhumanitarian reasons, including over 38,000 Hungariannationals beginning in 1956 and over a million Indochinesebeginning in 1975.6The CAM program provided parents who were lawfully present in the United States theopportunity to be considered for refugee resettlement for their unmarried children. Minorswho were determined to be ineligible for refugee status were then considered for parole intothe United States. Under some circumstances, an in-country parent could also be approvedto travel with the approved child. Under the CAM program, 1,045 children were admitted in2016 while 2,057 were admitted in 2017. The program was phased out in 2018.

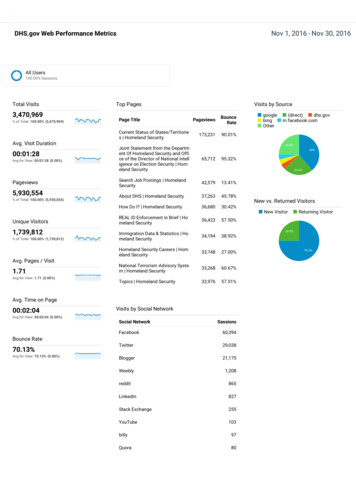

U.S. obligations under the 1967 United Nations Protocolrelating to the Status of Refugees (to which the United Statesacceded in 1968) generally prohibits the United States fromreturning a refugee to a country where his or her life orfreedom would be threatened on account of a protectedground. The Refugee Act of 1980 amended the INA to bringU.S. law into greater accord with U.S. obligations under theProtocol, which specifies a geographically and politicallyneutral refugee definition. The Act also established formalrefugee and asylum programs.foreign country. Any person who has ordered, incited, assisted,or otherwise participated in the persecution of another onaccount of race, religion, nationality, membership in aparticular social group, or political opinion is ineligible forrefugee status, including as a derivative refugee. Derivativerefugees need not meet all these eligibility requirements, butthey must be admissible to the United States and demonstratea relationship as the spouse or child of a principal refugeeapplicant or an admitted refugee.Refugee Admissions CeilingThe U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) establishesprocessing priorities that identify individuals and groups whoare of special humanitarian concern to the United States andwho are eligible for refugee resettlement consideration. Thepriority categories are Priority 1 (P-1)—individuals referredby UNHCR, a U.S. Embassy, or certain non-governmentalorganizations (NGO); Priority 2 (P-2)—groups of specialhumanitarian concern; and Priority 3 (P-3)—familyreunification cases. Once principal refugee applicants arereferred or granted access to USRAP under any of thesePriorities, they still must meet all other eligibility criteria.Upon referral, a Resettlement Support Center, working under acooperative agreement with the U.S. Department of State(DOS), conducts pre-screening interviews with the applicants.A U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) officerthen interviews applicants and accompanying derivatives todetermine eligibility for resettlement in the United States.Multiple security checks must be completed before a requestfor refugee status is approved. Additionally, applicants mustalso undergo a medical exam.Under the Refugee Act, the President consults with Congress toestablish an overall refugee admissions ceiling and regionalallocations before the beginning of each fiscal year.7 In 2017,the refugee ceiling was increased to 110,000. This was a 29percent increase from the previous year and a 57 percentincrease from the 2015 allocation. A pair of executive orderslater adjusted the 2017 admissions to 50,000.Similar to prior years, the largest regional allocations in 2017were to the Near East/South Asia and Africa regions (Table 1).These two regions host the majority of registered refugees,and together they accounted for close to 80 percent of allrefugee admissions to the United States. The largest numbers ofrefugees reside in Turkey (2.9 million, mainly Syrians andIraqis), Pakistan (1.4 million, mainly Afghans), and Lebanon(1 million, mainly Syrians).The office of the United Nations High Commissioner forRefugees (UNHCR) refers the majority of refugees who areresettled to the United States. While the numbers of refugeesUNHCR refers each year vary, the number of refugeesconsidered in need of resettlement is typically about eightpercent of the global refugee population, which has beenincreasing over the last few years, reaching 22.5 millionpeople by the end of the 2016 calendar year, the highestnumber ever recorded.8 Historically, the United States has beenthe world’s top resettlement country.Refugee Application ProcessIndividuals who successfully complete the application processare assigned to a resettlement agency (sponsor) that assistswith housing, employment, and other services upon arrival.The International Organization for Migration (IOM) makesarrangements for the refugee’s travel to the United States. Afterarrival, refugees are authorized to work and may requestdocumentation to travel outside the United States.Refugee Eligibility RequirementsTable 1.To qualify for refugee status, a principalapplicant must: (1) be of specialhumanitarian concern to the UnitedStates; (2) meet the refugee definition asset forth in section 101(a)(42) of theINA; (3) be admissible under the INA (orbe granted a waiver of inadmissibility);and (4) not be firmly resettled in anyProposed and Actual Refugee Admissions by Regions: FY 2015 to 2017178In many cases, an unallocated reserve is alsodesignated which can be used in any region if theneed arises and only after notification to Congress.This number included 17.2 million people under UnitedNations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) mandateand 5.3 million Palestinian refugees registered by the UnitedNations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in theNear East (UNRWA).2017RegionTotal. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Africa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .East Asia . . . . . . . . . . . . .Europe/Central Asia . . . . .Latin America/Caribbean . .Near East/South Asia . . . .Unallocated Reserve . . . . 69,92022,47218,4562,3632,05024,579--– Represents zero.1Ceiling and admission numbers reflect revisions made each fiscal year.Source: U.S. Department of State.3

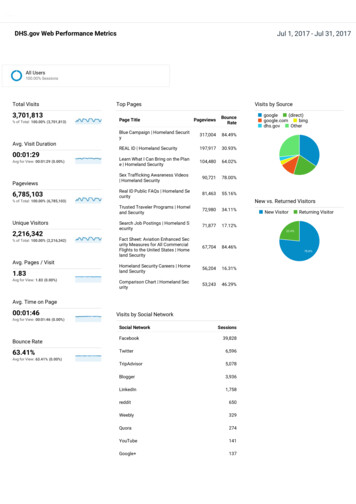

TRENDS AND CHARACTERISTICS OFREFUGEESFigure 1.Refugee Admissions and Proposed Ceilings to the United States: FY 1990 to 2017In 2017, the United States admitted 53,691refugees, a 37 percent decrease from the122,066140,000previous year, due in large part toActual AdmissionsProposed Ceilingsadditional security vetting procedures.120,000Refugee admissions under the current legal85,285framework peaked at 122,066 in 1990 and100,000then declined during the 1990s, as the80,000refugee program’s focus shifted to more53,691diverse populations across the world.60,000Admissions decreased to a low point in26,78540,0002002, due in part to security proceduresand admission requirement changes after20,000September 11, 2001. Refugee arrivalssubsequently increased and reached a post019901993199619992002200520082011201420172001 peak of 74,602 in 2009. After a briefYeardecrease from 2009 to 2011, refugeeSource: U.S. Department of State.admissions began to increase sharply againin 2012, reaching another peak of 84,989The spouse and unmarried children under the age of 21 of ain 2016, the highest in 17 years, reflecting staffing increasesprincipal refugee may obtain refugee status as an accompanyingand improvements in synchronizing security and medicalderivative.9 Accompanying derivatives may enter the Unitedchecks for refugee families (Figure 1).States with the principal refugee or within four months after theprincipal refugee’s admission.10 A spouse or child who joins theCategory of Admissionprincipal refugee more than four months after admission to theIn 2017, the majority of refugees were admitted under P-1United States is a follow-to-join derivative. Principal refugeesprocessing (62 percent)—individuals referred by the UNHCR,may petition for follow-to-join benefits for his or her qualifyinga U.S. Embassy, or certain NGOs—and P-2 processing (34derivatives up to two years after the principal was grantedpercent)—groups of special humanitarian concern (Table 2).refugee status; the principal and the derivative relative’sSimilar to 2016, P-3 processing (family reunification cases)relationship must have existed at the time of the principal’sconstituted 0.5 percent of refugees admitted due to a four-yearadmission into the United States. Principal refugees must filemoratorium. Principal refugees accounted for 21,507 (4011Form I-730, Refugee/Asylee Relative Petition, for each qualifyingpercent) of the 53,691 refugees admitted to the United Statesfollow-to-join derivative family member. These beneficiaries arein 2017. Accompanying spouses and dependent childrennot required to demonstrate an independent refugee claim.represented 14 and 46 percent, respectively, of refugeeOnce a principal’s I-730 has been approved, there are no timeadmissions. There were 1,679 follow-to-join refugeeconstraints placed upon that derivative relative’s travel to thebeneficiaries (about three percent of total refugee admissions).United States, provided that (1) the principal’s status has notbeen revoked; (2) the relationship of the derivative to theprincipal is unchanged; and (3) in the case of aTable 2.child, the child remains unmarried.DATAAll refugee data presented in this report arefrom the Worldwide Refugee AdmissionsProcessing System (WRAPS) of the Bureau ofPopulation, Refugees, and Migration of DOS.910114Children may include those age 21 or over who are covered byprovisions in the Child Status Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 107-208(Aug. 6, 2002). A derivative child must remain unmarried until thetime of admission to qualify.In practice, the vast majority of accompanying derivative refugeesenter the United States with the principal refugee.The petition is used to file for relatives of refugees and asylees. TheUSRAP program handles only refugee follow-to-join petitions, whichare counted within the annual refugee ceiling. Asylum follow-to-joinpetitions are processed by USCIS and are not counted in the annualadmission ceilings.Refugee Arrivals by Relationship to Principal Applicant and Case Priority:FY 2015 to 2017201720162015Relationship and case ATIONSHIP TOPRINCIPAL APPLICANTTotal. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Principal Applicant . . . . . . . . . .Dependents . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Spouse . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Child . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.9CASE PRIORITYTotal. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Priority 1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Priority 2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Priority 3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Follow-to-join beneficiaries . . . 55933,230962,035100.049.447.50.12.9Source: U.S. Department of State.

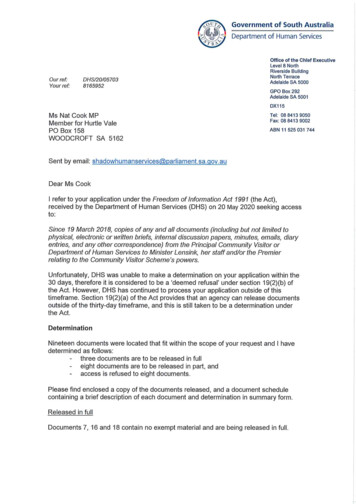

Country of NationalityIn 2017, the leading countries of nationality for individualsadmitted as refugees were the Democratic Republic of theCongo (17 percent), Iraq (13 percent), Syria (12 percent),Somalia (11 percent), and Burma (9.5 percent) (Table 3). Thesetop five countries made up close to two-thirds (63 percent) oftotal refugee admissions. Other leading countries includedUkraine, Bhutan, and Iran.Since the inception of the refugee program, the number andnationalities of refugees admitted to the United States changedas U.S. policies evolved and new conflicts around the worldarose. Since 2000 (the earliest year for which we have microdata), the United States has admitted more than a millionrefugees (1,063,078) from around the world. Sixteen percent(170,211) have been from Burma, 14 percent (147,650) fromIraq, and 11 percent (114,459) from Somalia (Figure 2).Refugees from the Near East/South Asia region accounted for athird of all refugee admissions during this time period. TheNear East/South Asia, Africa, and East Asia regions remainedthe leading regions of admissions in 2017 (33, 28, and 20percent of total admissions, respectively), despite eachexperiencing drops of at least 40 percent compared to 2016.Europe experienced a 32 percent increase in admission, whileLatin America and the Caribbean saw a 26 percent increase.Age, Sex, and Marital StatusThree quarters of refugees admitted to the United States in2017 were under 35 years of age, and three out of seven werechildren (Table 4). Refugees tend to be relatively younger thanthe native-born population, with a median age of 21 years forthose arriving in 2017, compared to a median age of 37 yearsfor the native-born population.12 Refugees admitted in 2017were slightly older than those admitted in 2016 (with amedian age of 20 years at arrival) but remain one of theyoungest cohorts since 2003. Refugee median age varieswidely by region and country of birth: Refugees from Africahad the lowest median age of 18 years, while those fromEurope had the highest median age of 24. The median ages ofCongolese, Iraqi, and Syrian refugees were 17, 25, and 16years, respectively. Roughly an equal number of male andfemale refugees were admitted in 2017, and 62 percent ofadults were married at arrival.State of Initial ResettlementTable 3.Refugee Arrivals by Country of Nationality: FY 2015 to 2017(Ranked by 2017 country of nationality)201720162015Country of Total. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Dem. Rep. Congo . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Iraq . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Syria . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Somalia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Burma . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Ukraine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Bhutan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Iran . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Eritrea . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Afghanistan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .All other countries, including 26.32.18.34.42.31.310.9In 2017, more than half of admittedrefugees (55 percent) were resettled in thetop ten resettling states (Table 5). Althoughthe most populous states—California, Texas,and New York—resettled the most refugees(10, 9.0, and 6.0 percent of admittedrefugees, respectively), Nebraska, NorthDakota, and Washington resettled the mostrefugees per capita (Figure 3). Iraqi andSomali refugees were among the topnationalities resettled in all three states,while Ukrainian refugees were the topnationality resettled in Washington State.Lawful Permanent Residence andNaturalization of RefugeesSource: U.S. Department of State.Figure 2.Refugee Arrivals by Top Country of Nationality: FY 2000 to a and HerzegovinaUkraineDem. Rep. CongoCubaIranBhutanSomaliaIraqBurmaAll Other CountriesOne year after being admitted to the UnitedStates, refugees are required by statute toapply for lawful permanent resident (LPR)status. Of those arriving between 2000 and2015, 95 percent gained LPR status by theend of 2017.13 Refugees granted LPR statusmay apply for naturalization five years aftertheir admission as refugees. Refugees havesome of the highest naturalization rates of allimmigrants: Of the adult refugees whoobtained LPR status between 2000 and 2010,60 percent naturalized within six years and12020,000 40,00060,00080,000 100,000 120,000 140,000 160,000 180,00013Source: U.S. Department of State.Calculated from the March 2017 Current Population Surveypublic use microdata file from the U.S. Census Bureau.Although the majority of refugees apply for LPR status oneyear after admission, due to operational and other factors,processing time can vary widely for those who apply.5

Table 4.Table 5.Refugee Arrivals by Age, Sex, and Marital Status:FY 2015 to 2017Refugee Arrivals by State of Residence: FY 2015 to 20172017CharacteristicNumberAGETotal. . . . . . .0 to 17 years . .18 to 24 years .25 to 34 years .35 to 44 years .45 to 54 years .55 to 64 years .65 yearsand over . . . . .(Ranked by 2017 state of 522.51,9062.21,8652.7SEXTotal. . . . . . .Female . . . . . . .Male . . . . . . . .Unknown . . . . 7.752.3–MARITALSTATUSTotal. . . . . . .Married1 . . . . . .Single2 . . . . . . .Other3 . . . . . . 52100.035.858.85.4Includes persons in common law marriage.2Includes persons who were engaged and not yet married.Per Capita Refugee Resettlement by State of Residence: FY 2017NDMNMIWYUTILOHINWVCOKSCAAZPAIANENVOKNMMOTX0 – 10 (16)VAKYNCTNSCARMSper 100,000 of StatePopulation(# of States)ALGALAFLAK26 – 42 (7)HIYear 2016Source: U.S. Department of State and U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division.73 within 10 years.14 For comparison, non-refugee immigrantswho obtained LPR status between 2000 and 2010 had 6- and10-year naturalization rates of 29 and 49 percent, respectively.146PercentTotal. . . . . . .California . . . . .Texas . . . . . . . .New York . . . . .Washington. . . .Ohio . . . . . . . . .Michigan. . . . . .Arizona . . . . . . .Pennsylvania. . .North Carolina. .Georgia . . . . . .Other . . . . . . . 146.9MESpouses and unmarried children under the ageof 2115 who are listed on the principal’s asylumRIapplication but not included in the principal’sCTNJgrant of asylum may obtain derivative asylumDEstatus. A principal asylee may petition ves up to two years after he or she wasgranted asylum, as long as the relationshipbetween principal spouse and/or child existedon the date the principal was granted asylum.16The principal asylee must file a Form I-730 foreach qualifying family member, who may belocated abroad or in the United States. Once anI-730 is approved for an individual locatedabroad, there are no time constraints placedupon the derivative relative’s travel to theUnited States, as long as (1) the principal’sstatus has not been revoked; (2) the relationship of thederivative to the principal is unchanged; and, (3) in the case ofa child, the child remains unmarried.NHNYWISDID43 – 74 (2)NumberVTWA11 – 15 (4)PercentGenerally, any foreign national present in the United States orarriving at a POE may seek asylum regardless of immigrationstatus. Those seeking asylum must apply within one year fromthe date of last arrival or establish that an exception appliesbased on changed or extraordinary circumstances. Principalapplicants obtain asylum in one of two ways: affirmativelythrough a USCIS asylum officer or defensively in removalproceedings before an immigration judge ofDOJ’s Executive Office for Immigration Review(EOIR). An individual applies for asylum byfiling Form I-589, Application for Asylum and forWithholding of Removal.Figure 3.16 – 25 (22)NumberFiling of ClaimsIncludes persons who were divorced, seperated, widowed, or of unknown marital status.Source: U.S. Department of State.OR2015PercentASYLEES3MT2016NumberSource: U.S. Department of State.– Represents zero.12017State ofresidenceThe data were restricted to immigrants who were 18 years of age and older when LPRstatus was obtained. More recent cohorts, with less time spent in LPR status, tend to havelower cumulative naturalization rates.MA1516See reference to Child Status Protection Act, n. 11, supra.In practice, the vast majority of derivative asylum status beneficiaries receive follow-to-joinbenefits.

Adjudication of ClaimsDATAThe USCIS Asylum Division adjudicates claims and may grantasylum directly through the affirmative asylum process.During interviews, asylum officers determine if the applicantmeets the definition of a refugee, is credible, is not barredfrom obtaining asylum, and warrants a grant of asylum as amatter of discretion. Individuals may be barred for previouslycommitting certain crimes, posing a national security threat,engaging in the persecution of others, or firmly resettling inanother country before coming to the United States.The affirmative asylee data presented in this report wereobtained from the Refugee, Asylum, and Parole System (RAPS)of USCIS. Defensive asylee data were obtained from EOIR.Follow-to-join asylum derivative data for people residingoutside the United States at the time of their admission wereobtained from the Case and Activity Management forInternational Operations (CAMINO) system of USCIS and theConsular Consolidated Database (CCD) of DOS. These datareflect travel documents issued, not admissions. Follow-to-joindata for people residing within the United States at the time ofthe approval of their I-730 petition were obtained from theComputer-Linked Application Information ManagementSystem (CLAIMS) of USCIS.If applicants with a valid immigration status (e.g., a foreignstudent) fail to establish eligibility for asylum, USCIS deniesthe application, and the applicant remains in his or her validstatus. If applicants are not in a valid status and are foundineligible for asylum, USCIS places these applicants in removalproceedings before an EOIR immigration judge, where theapplication is considered anew.Individuals who have not previously filed for asylum mayapply defensively after being placed in removal proceedings byimmigration enforcement officials because they are illegallypresent, are in violation of their status when apprehended, orwere apprehended while attempting to illegally enter theUnited States without proper documentation. Defensiveapplicants file for asylum directly with EOIR. During theproceedings, an immigration judge may grant asylum or denythe asylum application and issue a removal order. Applicantsmay appeal a denial to the Board of Immigration Appeals and,if unsuccessful there, may seek further review by a U.S. Courtof Appeals, and finally the Supreme Court.Asylum follow-to-join beneficiaries are not required todemonstrate a persecution claim because their status isderived from the principal asylee. Beneficiaries in the UnitedStates at the time of application are granted derivative asylumimmediately upon the approval of their I-730 petitions.Beneficiaries abroad at the time of application are grantedderivative asylum when admitted into the United States at a POE.Lawful Permanent Residence andCitizenshipOne year after being granted asylum,asylees are eligible to apply for LPRstatus along with qualifying familymembers who meet the eligibilitycriteria. Asylees may apply fornaturalization five years after their finalgrant of asylum, provided they appliedfor and were granted LPR status.1717Asylees may count a maximum of one year of theirtime in asylum status toward the required five yearsof permanent residence for naturalization eligibilitypurposes.TRENDS AND CHARACTERISTICS OF ASYLEESAsylum FilingsUSCIS received an estimated 139,801 affirmative asylumapplications18 in 2017, 21 percent more than the year beforeand close to a 150 percent increase since 2014 (Table 6a). Thisis the eighth consecutive annual increase and the highest levelsince 1995, when USCIS received close to 144,000applications. Applications from Venezuelans increased thirteenfold since 2014 to reach 27,579 in 2017.19The number of affirmative asylum applications by individualsfrom Central America’s Northern Triangle Countries (El Salvador,Guatemala, and Honduras) continues to rise. In the past fiveyears, applications rose from 3,523 in 2012 to 31,066 in 2017,an almost 800 percent increase. Unaccompanied children filedthe majority of affirmative asylum applications from theNorthern Triangle Countries, making up 66 percent of theapplications in 2015 and 56 percent in both 2016 and 2017.1819These include principal applican

(OIS) Annual Flow Report presents information on persons admitted to the United States as refugees and those who entered the U.S. asylum process in 2017.1 A total of 53,691 persons2 were admitted to the United States as refugees during 2017. The leading countries of nationality for refugees admitted during this period were the Democratic