Transcription

Clinical PracticeGuideline Summary:Bell’s PalsyReginald Baugh, MD; Gregory Basura,MD, PhD; Lisa Ishii, MD, MHS; SethR. Schwartz, MD, MPH; Caitlin MurrayDrumheller; Rebecca Burkholder,JD; Nathan A. Deckard, MD; CindyDawson, MSN, RN, CORLN; ColinDriscoll, MD; M. Boyd Gillespie,MD, MSc; Richard K. Gurgel, MD;John Halperin, MD, FAAN; AyeshaN. Khalid, MD; Kaparaboyna AshokKumar, MD, FRCS, FAAFP; AlanMicco, MD; Debra Munsell, DHSc,PA-C, DFAAPA; Steven Rosenbaum,MD, FAAEM; William VaughanThis month, the American Academyof Otolaryngology—Head andNeck Surgery Foundation (AAOHNSF) published its latest clinical practiceguideline, Bell’s Palsy, as a supplement toOtolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.Recommendations developed encourage accurate and efficient diagnosis andtreatment and, when applicable, facilitatingpatient follow-up to address the management of long-term sequelae, or evaluation of new or worsening symptoms notindicative of Bell’s palsy. The guideline34AAO-HNS Bulletin NOVEMBER 2013was developed using the a priori protocoloutlined in the AAO-HNS Clinical PracticeGuideline Development Manual.1 Thecomplete guideline is available at http://oto.sagepub.com.To assist in implementing the guidelinerecommendations, this article summarizesthe rationale, purpose, and key action statements. Recommendations in a guidelinecan be implemented only if they are clearand identifiable. This goal is best achievedby structuring the guideline around aseries of key action statements, which aresupported by amplifying text and actionstatement profiles. For ease of reference only the statements and profiles areincluded in this brief summary. Please referto the complete guideline for the importantinformation in the amplifying text thatfurther explains the supporting evidenceand details of implementation for each keyaction statement.For more information about the AAOHNSF’s other quality knowledge products(clinical practice guidelines and clinicalconsensus statements), our guideline development methodology, or to submit a topicfor future guideline development, pleasevisit ��s palsy, named after the Scottishanatomist, Sir Charles Bell, is the mostcommon acute mononeuropathy, ordisorder affecting a single nerve, and is themost common diagnosis associated withfacial nerve weakness/paralysis.1 Bell’spalsy is a rapid unilateral facial nerveparesis (weakness) or paralysis (completeloss of movement) of unknown cause. Thecondition leads to the partial or completeinability to voluntarily move facial muscleson the affected side of the face. Althoughtypically self-limited, the facial paresis/paralysis that occurs in Bell’s palsy maycause significant temporary oral incompetence and an inability to close the eyelid,leading to potential eye injury. Additionallong-term poor outcomes do occur and canbe devastating to the patient. Treatmentsare generally designed to improve facialfunction and facilitate recovery.The myriad treatment options for Bell’spalsy include medical therapy (steroids andantivirals, alone and in combination),2-4 surgical decompression,5-8 and complementaryand alternative therapies such as acupuncture. Some controversy exists regarding

Doctor,Please ExplainBell’s PalsyWhat else can you do?our condition does not improve over time, theree some procedures that can help reduce the effectsBell’s palsy. For instance, you can get specializedp with closing the eye. It is also very importantat you watch your mental health and that you seekunseling or support if you feel overwhelmed by they your face has changed. You should follow up withur doctor, should your symptoms not get betterhin three months or if symptoms worsen. Yourctor can review your past treatment and explorether options with you to help you treat yourmptoms. Your doctor may refer you to a specialisthelp with managing your symptoms.This plain language summary was developed from the2013 AAO-HNSF Clinical Practice Guideline: Bell’spalsy. The multidisciplinary guideline developmentgroup represented the fields of otolaryngology–headand neck surgery, neurology, facial plastic andreconstructive surgery, neurotology, emergencymedicine, primary care, otology, nursing, physicianassistants, and consumer advocacy. Literature searchesfor the guideline were conducted up through February2013. For more information on Bell’s palsy, fmtoday’s world of social media, there are a numberwebsites with patients who are sharing life storiesd pictures or videos of how they have coped—oftenh creative humor and good spirit—and how theirndition has improved over time. We do not endorsey specific Bell’s related website and some sitesve bad information. However, you may find comfortoining online support discussion forums. Theseine forums offer a place where you can learnd share with others with Bell’s, who understandat you are going through. These sites can providecouragement, useful coping tips, and hope. nWhat Is an Otolaryngologist—Head and Neck Surgeon?(Ear, Nose, and Throat Specialist)An otolaryngologist is a physician specially trainedto provide medical and surgical treatment to the ears,nose, throat, and related structures of the headand neck.The American Academy of Otolaryngology—Headand Neck Surgery represents approximately 12,000ear, nose, and throat specialists. For more informationor a list of otolaryngologists practicing in your area,please visit our website at www.entnet.org, orcontact the Academy.Bell’s PalsyGuidelineInsight into Bell’s Palsy,including:n What is Bell’s palsy?n How is it treated?n What if I don’t fully recover?A Recycled and Recyclable Paper 2013 American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery1650 Diagonal Road, Alexandria, VA 22314-2857For more information, visit our website at www.entnet.orgPLEAF4763045Empowering physicians to deliver the best patient careThe AAO-HNSF’slatest guideline isnow available atwww.otojournal.organd on www.entnet.orgEmpowering physicians to deliver the best patient carethe effectiveness of several of these optionsand there are consequent variations in care.Additionally, there are numerous diagnostictests available that are used in the evaluation of Bell’s palsy patients. Many of thesetests are of questionable benefit in Bell’spalsy, including laboratory testing,9,10diagnostic imaging studies, and electrodiagnostic tests.10-12 Furthermore, whileBell’s palsy patients enter the healthcaresystem with facial paresis/paralysis asa primary complaint, not all patientswith facial paresis/paralysis have Bell’spalsy. It is a concern that patients withalternative underlying etiologies may bemisdiagnosed or have unnecessary delayin diagnosis. All of these quality concernsprovide an important opportunity forimprovement in the diagnosis and management of patients with Bell’s palsy.When evaluating a patient with facialweakness/paralysis for Bell’s palsy, thefollowing should be considered: Bell’s palsy is rapid in onset ( 72hours). Bell’s palsy is diagnosed when no othermedical etiology is identified as a causeof the facial weakness. Bilateral Bell’s palsy is rare.13,14 Currently, no cause for Bell’s palsy hasbeen identified. Other conditions may cause facialparalysis, including stroke, brain tumors,tumors of the parotid gland or infratemporal fossa, cancer involving thefacial nerve, and systemic and infectiousdiseases including zoster, sarcoidosis,and Lyme disease.1,15-17 Bell’s palsy is typically self-limited. Bell’s palsy may occur in men, women,and children, but is more commonin those 15-45 years old; those withdiabetes, upper respiratory ailments, orcompromised immune systems; or during pregnancy.1,6,18The guideline development group(GDG) recognizes that Bell’s palsy is adiagnosis of exclusion requiring the carefulelimination of other causes of facial paresisor paralysis. Although the literature is silenton the precise definition of what constitutesacute onset in facial paralysis, the GDGaccepted the definition of “acute” or “rapidonset” to mean that the occurrence ofparesis/paralysis typically progresses to itsmaximum severity within 72 hours of onsetof the paresis/paralysis. This guidelinedoes not focus on facial paresis/paralysisdue to neoplasms, trauma, congenital orsyndromic problems, specific infectiousagents, or post-surgical facial paresis orparalysis; nor does it address recurrentfacial paresis/paralysis. For the purposesof this guideline, Bell’s palsy is definedas: Acute unilateral facial nerve paresis orparalysis with onset in less than 72 hoursand without an identifiable cause.Literature cited throughout this guidelineoften uses the House-Brackmann facialnerve grading scale. This is a commonlyused scale designed to systematicallyquantify facial nerve functional recoveryafter surgery that puts the facial nerve atrisk, but has been used to assess recoveryafter trauma to the facial nerve, or Bell’spalsy.19 It was not designed to assess initialfacial nerve paresis or paralysis of Bell’spalsy. The House-Brackmann facial nervegrading system is described in Table 1.While a viral etiology is suspected, theexact mechanism of Bell’s palsy is currently unknown.21 Facial paresis or paralysis is thought to result from facial nerveinflammation and edema. As the facialnerve travels in a narrow canal within thetemporal bone, swelling may lead to nervecompression and result in temporary orAAO-HNS Bulletin NOVEMBER 201335

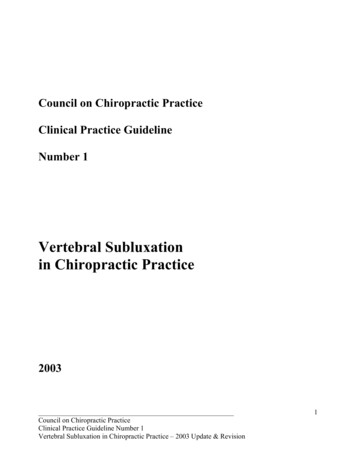

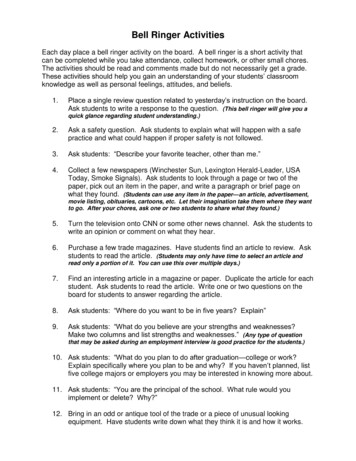

feature: Bell’s PalsyTable 1. House-Brackmann Facial Nerve Grading System20GradeDefined by1NormalNormal facial function in all areas.2Mild dysfunctionSlight weakness noticeable only on close inspection. At rest: normal symmetry of forehead, abilityto close eye with minimal effort and slight asymmetry, ability to move corners of mouth withmaximal effort and slight asymmetry. No synkinesis, contracture, or hemifacial spasm.3ModeratedysfunctionObvious, but not disfiguring difference between two sides, no functional impairment; noticeable,but not severe synkinesis, contracture, and/or hemifacial spasm. At rest: normal symmetry andtone. Motion: slight to no movement of forehead, ability to close eye with maximal effort andobvious asymmetry, ability to move corners of mouth with maximal effort and obvious asymmetry.Patients who have obvious, but no disfiguring synkinesis, contracture, and/or hemifacial spasm aregrade III regardless of degree of motor activity.4Obvious weakness and/or disfiguring asymmetry. At rest: normal symmetry and tone. Motion: noModerately severe movement of forehead; inability to close eye completely with maximal effort. Patients with synkidysfunctionnesis, mass action, and/or hemifacial spasm severe enough to interfere with function are grade IVregardless of motor activity.5SeveredysfunctionOnly barely perceptible motion. At rest: possible asymmetry with droop of corner of mouth anddecreased or absence of nasal labial fold. Motion: no movement of forehead, incomplete closureof eye and only slight movement of lid with maximal effort, slight movement of corner of mouth.Synkinesis, contracture, and hemifacial spasm usually absent.6Total paralysisLoss of tone; asymmetry; no motion; no synkinesis, contracture, or hemifacial spasm.permanent nerve damage. The facialnerve carries nerve impulses to musclesof the face, and also to the lacrimalglands, salivary glands, stapediusmuscle, taste fibers from the anteriortongue, and general sensory fibers fromthe tympanic membrane. Accordingly,patients with Bell’s palsy may experience dryness of the eye or mouth, tastedisturbance or loss, hyperacusis, andsagging of the eyelid or corner of themouth.13,18 Ipsilateral pain around the earor face is not an infrequent presentingsymptom.21,22Numerous diagnostic tests have beenused to evaluate patients with acutefacial paresis/paralysis for identifiablecauses, or aid in predicting long-termoutcomes. Many of these tests wereconsidered in the development of thisguideline, including: Imaging—Computed tomography(CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—to identify potentialinfection, tumor, fractures, or other36AAO-HNS Bulletin potential causes for facial nerveinvolvement; Electrodiagnostic testing to stimulatethe facial nerve to assess the level offacial nerve insult; Serologic studies to test for infectiouscauses; Hearing testing to determine if thecochlear nerve or inner ear has beenaffected; Vestibular testing to determine if thevestibular nerve is involved; and Schirmer’s tear testing to measure theeye’s ability to produce tears.Most patients with Bell’s palsy showsome recovery without interventionwithin two to three weeks after onsetof symptoms, and completely recoverwithin three to four months.1 Moreover,even without treatment, facial function is completely restored in nearly70 percent of Bell’s palsy patients withcomplete paralysis within six months,and as high as 94 percent of patientswith incomplete paralysis; accordingly,as many as 30 percent of patients doNOVEMBER 2013not recover completely.23,24 Given thedramatic effect of facial paralysis onpatient appearance, quality of life, andpsychological well-being, treatment isoften initiated in an attempt to decreasethe likelihood of incomplete recovery.Corticosteroids and antiviral medications are the most commonly used medical therapies. New trials have exploredthe benefit of these medications. Thebenefit of surgical decompression ofthe facial nerve remains relativelycontroversial.23,25There are both short- and long-termsequelae of Bell’s palsy, including aninability to close the eye, drying andcorneal ulceration of the eye, and visionloss. These can be prevented with appropriate eye care. The short-term sequelae,such as inability to close the eye anddrying of the eye warrant careful management, but treatment results can befavorable. Long-term, the disfigurementof the face due to incomplete recoveryof the facial nerve can have devastatingeffects on psychological well-being and

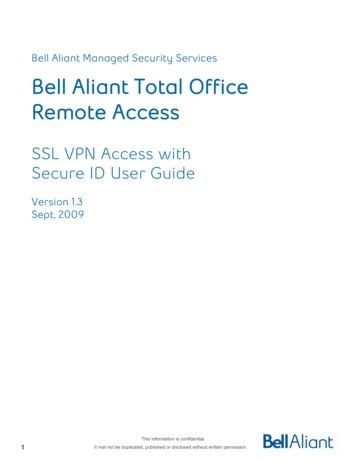

feature: Bell’s Palsyquality of life. With diminished facialmovement and marked facial asymmetry, patients with facial paralysis canhave impaired interpersonal relationships and may experience profoundsocial distress, depression, and socialalienation.26 There are a number of rehabilitative procedures to normalize facialappearance, including eyelid weightsor springs, muscle transfers and nervesubstitutions, static and dynamic facialslings, and botulinum toxin injections toeliminate facial spasm/synkinesis.27-31 Thisguideline will, however, focus more on theacute management of Bell’s palsy and willnot address these interventions in detail.Purposeto limit treatment or care provided toindividual patients. The guideline is notintended to replace clinical judgment forindividualized patient care. Our goal is tocreate a multidisciplinary guideline with aspecific set of focused recommendationsbased upon an established and transparentprocess that considers levels of evidence,harm-benefit balance, and expert consensus to resolve gaps in evidence. Thesespecific recommendations are designed toimprove quality of care and may be usedto develop performance measures.Key Action StatementsSTATEMENT 1. PATIENT HISTORYAND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION:accurate diagnosis; avoidance ofunnecessary testing and treatment;identification of patients for whomother testing or treatment is indicated;opportunity for appropriate patientcounseling Risks, harms, costs: None Benefit-Harm Assessment:Preponderance of benefit Value judgments: The GDG felt thatassessment of patients cannot be performed without a history and physicalexamination, and that it would not bepossible to find stronger evidence, asstudies excluding these steps cannotethically be performed. Other causes offacial paresis/paralysis may go unidentified; a thorough history and physicalexamination will help avoid misseddiagnoses or diagnostic delay. Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: None Exceptions: None Policy level: Strong recommendation Differences of opinion: NoneThe primary purpose of this guidelineClinicians should assess the patientis to improve the accuracy of diagnosisusing history and physical examinationfor Bell’s palsy, to improve the qualityto exclude identifiable causes of facialof care and outcomes for Bell’s palsyparesis or paralysis in patients presentpatients, and to decrease harmful variaing with acute onset unilateral facialtions in the evaluation and managementparesis or paralysis. Strong recommendaof Bell’s palsy. This guideline addressestion based on observational studies ofthese needs by encouraging accuratealternative causes of facial paralysis andand efficient diagnosis and treatmentreasoning from first principles, with aSTATEMENT 2. LABORATORYand, when applicable, facilitating patientpreponderance of benefit over harm.TESTING:follow-up to address the management ofClinicians should not obtain routinelong-term sequelae, or evaluation of newlaboratory testing in patients with newAction Statement Profileor worsening symptoms not indicative ofonset Bell’s palsy. Recommendation Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade CBell’s palsy. The guideline is intended for(against) based on observational studies Level of confidence in evidence: Highall clinicians in any setting who are likelyand expert opinion with a preponderance Benefit: Identification of other causesto diagnose and manage patients withof benefit over harm.of facial paresis/paralysis, enablingBell’s palsy. The targetpopulation is inclusiveof both adults andTable 2. Abbreviations and Definitions of Common Termschildren presenting withBell’s palsy.TermDefinitionThis guideline isintended to focus on aAcuteOccurring in less than 72 hourslimited number of qualBell’s palsyAcute unilateral facial nerve paresis or paralysis with onset in less thanity improvement oppor72 hours and without identifiable causetunities deemed mostimportant by the GDG,Electromyography (EMG)A test in which a needle electrode is inserted into affected muscles toand is not intended to be testingrecord both spontaneous depolarizations and the responses to voluntary muscle contractiona comprehensive guidefor diagnosing andElectroneuronography (ENoG)A test used to examine the integrity of the facial nerve, in whichmanaging Bell’s palsy.testing (neurophysiologicsurface electrodes record the electrical depolarization of facial musclesThe recommendationsstudies)following electrical stimulation of the facial nerveoutlined in this guideline are not intended toFacial paralysisComplete inability to move the facerepresent the standard ofIncomplete ability to move the facecare for patient manage- Facial paresisment, nor are the recom- IdiopathicWithout identifiable causemendations intendedAAO-HNS Bulletin NOVEMBER 201337

feature: Bell’s PalsyAction Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade C Level of confidence in evidence: High Benefit: Avoidance of unnecessarytesting and/or treatment, avoidance ofpursuing false positives, cost savings Risks, harms, costs: Potential misseddiagnosis Benefit-harm assessment:Preponderance of benefit Value judgments: While the GDG feltthat there are circumstances wherespecific testing is indicated in at-riskpatients (such as Lyme disease serologyin endemic areas) these patients canusually be identified by history. Intentional vagueness: We used theword “routine” to specify that undercertain circumstances, laboratory testingmay be indicated. Role of patient preferences: Small(there is an opportunity for patienteducation) Exceptions: None Policy level: Recommendation (against) Differences of opinion: NoneSTATEMENT 3. DIAGNOSTICIMAGING:Clinicians should not routinelyperform diagnostic imaging forpatients with new onset Bell’s palsy.Recommendation (against) based onobservational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm.Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade C Level of confidence in evidence: High Benefit: Avoidance of unnecessaryradiation exposure, avoidance of incidental findings, avoidance of contrastreactions, cost savings Risks, harms, costs: Risk of missingother cause of facial paresis/paralysis Benefit-harm assessment:Preponderance of benefit Value judgments: None Intentional vagueness: The word “routine” was used to indicate there maybe some clinical findings that wouldwarrant imaging Role of patient preferences: Small, however there is an opportunity for patienteducation/counseling Exceptions: None38AAO-HNS Bulletin Policy level: Recommendation (against) Differences of opinion: NoneSTATEMENT 4. ORAL STEROIDS:Clinicians should prescribe oral steroids within 72 hours of symptom onsetfor Bell’s palsy patients 16 years andolder. Strong recommendation based onhigh-quality randomized controlled trialswith a preponderance of benefit over harm.Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade A Level of confidence in evidence: High Benefit: Improvement in facial nervefunction, faster recovery Risks, harms, costs: Steroid side effects,cost of therapy Benefit-harm assessment:Preponderance of benefit Value judgments: None Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: Small Exceptions: Diabetes, morbid obesity,previous steroid intolerance, andpsychiatric disorders. Pregnant womenshould be treated on an individualizedbasis. Policy level: Strong recommendation Differences of opinion: NoneSTATEMENT 5A. ANTIVIRALMONOTHERAPY:Clinicians should not prescribe oralantiviral therapy alone for patientswith new onset Bell’s palsy. Strongrecommendation (against) based on highquality randomized controlled trials with apreponderance of benefit over harm.Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade A Level of confidence in evidence: High Benefit: Avoidance of medication sideeffects, cost savings Risks, harms, costs: None Benefit-harm assessment:Preponderance of benefit Value judgments: None Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: Small Exceptions: None Policy level: Strong recommendation(against) Differences of opinion: NoneNOVEMBER 2013STATEMENT 5B. COMBINATIONANTIVIRAL THERAPY:Clinicians may offer oral antiviraltherapy in addition to oral steroidswithin 72 hours of symptom onset forpatients with Bell’s palsy. Option basedon randomized controlled trials withminor limitations and observational studies with equilibrium of benefit and harm.Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade B Level of confidence in evidence:Medium, because the studies cannotexclude a small effect Benefit: Small potential improvementin facial nerve function Risks, harms, costs: Treatment sideeffects, cost of treatment Benefit-harm assessment:Equilibrium of benefit and harm Value judgments: Although the datawere weak, the risks of combinationtherapy were small Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: Large;significant role for shared decisionmaking Exceptions: Diabetes, morbid obesity, and previous steroid intolerance.Pregnant women should be treated onan individualized basis. Policy level: Option Differences of opinion: NoneSTATEMENT 6. EYE CARE:Clinicians should implement eyeprotection for Bell’s palsy patientswith impaired eye closure. Strong recommendation based on expert opinionand a strong clinical rationale with apreponderance of benefit over harm.Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade X Level of confidence in evidence:High. Eye protection has been thestandard of care, and comparativestudies with a no treatment arm areunethical. Benefit: Prevention of eyecomplications Risks, harms, costs: Cost of eye protection implementation, potential sideeffects of eye medication

feature: Bell’s Palsy Benefit-harm assessment: Preponderanceof benefit over harm Value judgments: None Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: Small Exceptions: None Policy level: Strong recommendation Differences of opinion: NoneSTATEMENT 7A.ELECTRODIAGNOSTIC TESTINGWITH INCOMPLETE PARALYSIS:Clinicians should not performelectrodiagnostic testing in Bell’s palsypatients with incomplete facial paralysis. Recommendation (against) based onobservational studies with a preponderanceof benefit over harm.Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade C Level of confidence in evidence: High Benefit: Avoidance of unnecessary testing, cost savings Risks, harms costs: None Benefit-harm assessment: Preponderanceof benefit over harm Value judgments: None Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: None Exceptions: None Policy Level: Recommendation (against) Differences of opinion: NoneSTATEMENT 7B.ELECTRODIAGNOSTIC TESTINGWITH COMPLETE PARALYSIS:Clinicians may offer electrodiagnostictesting to Bell’s palsy patients withcomplete facial paralysis. Option basedon observational trials with equilibrium ofbenefit and harm.Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade C Level of confidence in evidence:Medium due to variations in patientselection, study design, and heterogeneous results Benefit: Provide prognostic informationfor the clinician and patient, identification of potential surgical candidates Risks, harms, costs: Patient discomfort,cost of testing Benefit-harm assessment: Equilibrium ofbenefit and harm40AAO-HNS Bulletin Value judgments: None Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: Large rolefor shared decision making, as electrodiagnostic testing may provide onlyprognostic information for the patient Exceptions: None Policy level: Option Differences of opinion: NoneSTATEMENT 8. SURGICALDECOMPRESSION:No recommendation can be maderegarding surgical decompression forBell’s palsy patients. No recommendationbased on low-quality, non-randomized trials and equilibrium of benefit and harm.Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade D Level of confidence in evidence: Lowdue to insufficient number of patientsand poor quality of studies. Low confidence in the evidence led to a downgradeof the aggregate evidence quality fromC to D. Benefit: Improved facial nerve functionalrecovery Risks, harms, costs: Surgical risks andcomplications, anesthetic risks, directand indirect costs of surgery Benefit-harm assessment: Equilibrium ofbenefit and harm Value judgments: Although the data supporting surgical decompression are notstrong, there may be a significant benefitfor a small subset of patients who meeteligibility criteria and desire surgicalmanagement Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: Large. Thepsychological impact of facial paralysisis significant but varies among patients.Concern about the facial deformitymay make some patients willing topursue a major operation for a smallincrease in the chance of completerecovery while others may be morewilling to accept the chance of pooreroutcome to avoid surgery. Exceptions: None Policy level: No recommendation Differences of opinion: Major. The groupwas divided as to whether the evidencesupported no recommendation, or anoption for surgery. This difference ofNOVEMBER 2013opinion derived from controversy regarding the strength of evidence (C levelevidence vs. D level evidence.)STATEMENT 9. ACUPUNCTURE:No recommendation can be maderegarding the effect of acupuncture inBell’s palsy patients. No recommendation based on poor quality trials and anindeterminate ratio of benefit and harm.Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade B Level of confidence in evidence: Low,due to significant methodological flawsin available evidence Benefit: Acupuncture may provide apotential small improvement in facialnerve function and pain Risks, harms, costs: Cost of acupuncture therapy, time required for therapy,therapy side effects, and delay in instituting steroid therapy Benefit-harm assessment: Unknown Value judgments: Due to the poor quality of the data and the inability to determine harm to benefit ratio, the GDGcould not make a recommendation. Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: Large Exceptions: None Policy level: No recommendation Differences of opinion: Major. TheGDG was divided regarding whetherto recommend against acupuncture, orto make no recommendation.STATEMENT 10. PHYSICALTHERAPY:No recommendation can be maderegarding the effect of physicaltherapy in Bell’s palsy patients. Norecommendation based on case seriesand equilibrium of benefit and harm.Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade D Level of confidence in evidence:Low, due to significant flaws inexisting trials Benefit: Potential functional and psychological benefit Risks, harms, costs: Cost of therapy,time required for therapy Benefit-harm assessment: Equilibriumof benefit and harm

feature: Bell’s Palsy Value judgments: Patients may benefit psychologically from engaging inphysical therapy exercises Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: Large rolefor shared decision making Exceptions: None Policy level: No recommendation Differences of opinion: NoneSTATEMENT 11. PATIENTFOLLOW-UP:Clinicians should reassess or referto a facial nerve specialist those Bell’spalsy patients with (1) new or worsening neurologic findings at any point,(2) ocular symptoms developing at anypoint, or (3) incomplete facial recoverythree months after initial symptomonset. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance ofbenefit over harm.Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade C Level of confidence in evidence: High Benefit: Reevaluation for alternatediagnoses of facial paralysis, discussion of therapeutic/reconstructiveoptions, psychological support ofpatient Risks, harms, costs: Cost of visit, timededicated to visit Benefit-ha

www.entnet.org Bulletin))) -.)