Transcription

Research BriefJohanna Lacoe, Mathematica and Hannah Betesh, Social Policy Research AssociatesSupporting Reentry Employment andSuccess: A Summary of the Evidencefor Adults and Young AdultsEmployment is a potential source of stability andopportunity for Americans trying to better theirlives after involvement with the criminal justicesystem. The path to employment can be difficult forthis population, however, and the challenges differdepending on age. Adults often enter the justicesystem with barriers to employment and struggleto reconnect to the labor market after their releasefrom incarceration, due to such factors as limitedbasic skills and soft skills, employers’ reluctanceto hire people with criminal records, and difficultyretaining stable employment because of unstablehousing, lack of adequate transportation, or mentalhealth problems. Young adults (ages 18 to 24) aredevelopmentally different from adults; therefore,programs that improve outcomes for adults mayneed to be tailored to address the specific needsof young adults before they show similar results.Disruptions in education due to court involvementearly in the lives of young adults can derail futureemployment opportunities, without appropriateinterventions. Both populations need support inconnecting to employment after justice systeminvolvement. This issue brief maps the evidenceand remaining gaps in the knowledge base oninterventions for these groups ahead of a nationalevaluation of employment-focused reentry programsserving justice-involved adults and young adults.Key FindingsThis brief reviews research on employment,cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and casemanagement models for justice-involved adultsand young adults and finds: Most prior studies of adult employment reentryprograms do not consistently show effects dueto variation in program models, implementation quality, and study designs. Reentry programs specifically tailored to youngadults often include job training or employment support, but evidence of employmentimpacts is limited. CBT interventions reduce recidivism for justice-involved adults, but impacts on youngadults and on employment outcomes areunknown. The ongoing REO evaluation (2017-2022) hasthe potential to provide evidence on strategiesto reduce recidivism and increase employmentfor justice-involved individuals.Reentry Employment Opportunities EvaluationUnder contract from DOL, Mathematica Policy Research and Social Policy Research Associates (SPR) are conducting an evaluation of the REO grant program.The implementation and impact studies aim to build evidence about effective strategies to serve people with prior justice involvement and facilitate theirsuccessful reentry into the community.SEPTEMBER 2019 mathematica-mpr.com1

Reentry Employment Opportunities Research BriefReentry EmploymentOpportunities grantsand evaluationFor more than a decade, the U.S. Department of Labor(DOL) has invested in reentry services by committingsubstantial funding toward programs serving justice-involved young adults and adults, under a fundingumbrella currently known as the Reentry EmploymentOpportunities (REO) program in the Employment andTraining Administration. Between 2015 and 2018, DOLawarded more than 200 million in funds under threeREO grant opportunities: (1) 157.4 million in ReentryProject grants, (2) 31 million in Reentry Demonstration Project grants, and (3) 21 million in Training toWork grants. This funding targets young adults (ages18 to 24) and adults (ages 25 and over) with previousinvolvement in the criminal justice system. Programsfunded under these grant streams serve justice-involved populations using one or more approachesfor employment-focused services: registered apprenticeship, work-based learning, and career pathways.Although each of these grant programs offers different services, the overarching aim of the REO programis to improve employment outcomes and workforcereadiness for the target population through employment services, case management, and other supportive services, including legal services.REO Priority Employment StrategiesREO grantees were required to use at least one ofthe following employment strategies: registeredapprenticeship, work-based learning, and careerpathways. These strategies can be effective inhelping low-income populations improve labormarket outcomes, such as employment andearnings. Evidence includes quasi-experimentalevaluations of registered apprenticeships,experimental evaluations of career pathwaysprograms, and both experimental and quasiexperimental evaluations of sector strategies.1SEPTEMBER 2019 mathematica-mpr.comAbout this briefThis issue brief summarizes the evidence onprogram models for serving justice-involvedadults and young adults through connectionto employment, cognitive behavioral therapy,and case management services (Figure 1). Theprimary evidence of the effectiveness of thesemodels comes from a review of experimentaland quasi-experimental impact evaluations.Information about factors that may contributeto the successful implementation of the modelscomes from a review of outcome evaluations andimplementation studies. The brief closes with asummary of gaps in the knowledge base and anassessment of the potential contributions of theongoing REO evaluation to narrowing these gaps.Recognizing the opportunity to learn from the REOinitiative investments, DOL’s Chief Evaluation Officecontracted with Mathematica Policy Research andSocial Policy Research Associates to build evidenceabout what works to connect justice-involvedindividuals to employment in support of successfulreentry. The evaluation aims to identify innovativeways to provide services that will improve labormarket and criminal justice system outcomes ofREO participants.The 118 REO projects funded between 2015 and2018 consist of 78 unique grantees; 19 werefunded under more than one grant type, and 14were funded for two projects within the samegrant type. Most of these grants (88) went tocommunity-based organizations, which are organizations with single sites or multiple sites withinone state; the remaining 30 grants went to intermediary organizations, which are organizationsthat have an affiliate network or offices in at leastthree communities and across at least two states.Just over half of the grants (61) were for services2

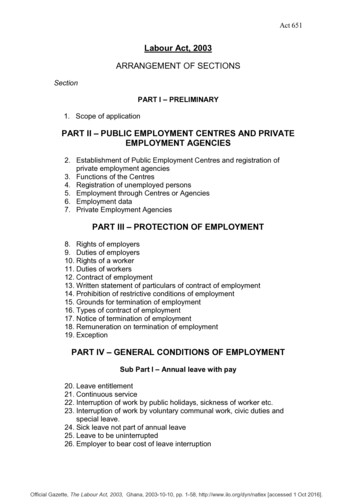

Reentry Employment Opportunities Research Briefexplicitly targeted to young adults aged 18–24.The grants predominately serve urban areas(105), with 1 grant serving a rural area only, and12 grants serving a mix of urban and rural areas.Expected enrollment ranged from 72 to 705 participants, with an average enrollment expectationof 261 participants per grant across all projects.As discussed in more detail throughout the brief,many of the REO grantees plan to combine structured employment experiences—through modelssuch as apprenticeship, work-based learning, andcareer pathways—with case management andsupportive services to facilitate the transition tounsubsidized employment.Evidence on existing programmodels for justice-involvedadultsEmployment can provide stability for peoplereentering society after incarceration, helpingprevent criminal activity and recidivism(Crutchfield and Pitchford 1997; Uggen 1999,2000; Laub and Sampson 2003). In the first yearafter release, however, just over half of peoplewith criminal records have any reported earnings(Looney and Turner, 2018). A key goal of the REOgrants is to support connection to employment forjustice-involved people through evidence-basedmodels. Most prior research on reentry employmentprograms focuses on models for adults, not youngadults. This section reviews the evidence on theeffectiveness of these employment-focused modelsfor improving labor market outcomes and reducingrecidivism among adults. It then reviews researchon cognitive-behavioral therapy and wraparoundservices (which, although not specifically designedto improve employment outcomes, are commoncomponents of employment-focused interventionsfor this population).Employment-focused programmingEmployment-focused models inthe existing literature include arange of interventions. Some ofthese approaches provide specificopportunities for employment. These approachesinclude work-release, which enables employmentduring incarceration, and transitional jobs,which provide temporary paid work experienceFigure 1: Common reentry program components for justice-involved young adults and adultsEmployment-focused programmingVocationaltrainingJob itionaljobsJustice-involvedyoung adultsCognitive behavioral therapyMoralreconationThinking fora -involvedadultsCase EPTEMBER 2019 mathematica-mpr.comCoachingTrauma-informedcare3

Reentry Employment Opportunities Research Briefopportunities. Other approaches focus on preparingfor a transition to employment. These approachesinclude vocational training, which providestraining for careers in specific industries, workreadiness training, which focuses on job searchskills and appropriate behavior in the workplace,and job search assistance, which providesindividualized support with job applicationsand job placement. Prior evidence exists onthe effectiveness and implementation of theseapproaches, discussed in more detail next.Through work-release, incarcerated people maywork outside the facility during the day, whichallows them to gain employment experienceduring incarceration, with the hope of easingtheir transition back into the community.Available evidence comes from quasi-experimentalevaluations in the states where these programshave operated long enough to have stable modelsand enough participation for an impact evaluation:Florida (Bales et al. 2016; Berk 2007), Minnesota(Duwe 2014a, 2014b), and Washington (Drake 2003,2007; Turner and Petersilia 1996). These studieshave not included implementation evaluations;however, because these models are somewhatprescribed by federal law, the interventions understudy usually shared common approaches. Theseapproaches include targeting inmates close torelease and in less restrictive prison units, housingindividuals in a work release center separate fromother inmates, and requiring that all nonwork hoursbe spent in that secure facility. To date, these quasiexperimental evaluations show improvements inpost-release employment rates (when that outcomeis measured) but they do not consistently point toreductions in recidivism.2There is also a growing body of work on usingtransitional jobs as a post-release employmentstrategy (Bloom 2010; Dutta- Gupta et al. 2016),and 88 REO grantees include similar temporary,paid work experience in their program models.Implementation studies of transitional jobs reentryprograms such as the Safer Return demonstration(Rossman and Fontaine 2015), the Transitional JobsSEPTEMBER 2019 mathematica-mpr.comReentry Demonstration (Redcross et al. 2010), theCenter for Employment Opportunities TransitionalJobs Program (Broadus et al. 2016), the MathematicaJobs Study (Maxwell et al. 2014), and the Los AngelesRegional Initiative for Social Enterprise (Geckeleret al. 2018), and the Enhanced Transitional JobsDemonstration (Redcross et al. 2016) underscore theimportance of effective coordination between serviceproviders and employers, and of dedicating resourcesto reduce attrition and address supportive serviceneeds. Impact studies of transitional jobs programsfor reentry populations include both experimental(Barden et al. 2018; Redcross et al. 2012; Butler et al.2012; Jacobs 2012; Cook et al. 2015; Uggen 2000) andquasi-experimental (Rotz et al. 2015; Fontaine et al.2015) evaluations, the majority of which demonstratefairly consistent findings. In the short term, theseapproaches increase employment, earnings, andwell-being, and reduce recidivism.3 In general, inmost of these studies, the effects do not persist afterparticipants complete transitional work experiences.Most recently, however, the Enhanced TransitionalJobs Demonstration (Barden et al. 2018) foundincreases in employment and earnings, as well asreductions in certain measures of recidivism (felonyconvictions, incarceration in prison, and total days ofincarceration) during the final year of follow-up, andthese impacts were concentrated among those at thehighest risk of recidivism. Similarly, one other studyfound reductions in recidivism for participants overage 27 (Uggen 2000).Vocational training allows participants to trainfor specific occupations and can include awardingof certificates or credentials. Meta-analyses ofevaluations on these models (Davis et al. 2013; Aoset al. 2006; MacKenzie 2006) primarily focus onquasi-experimental studies of vocational trainingwhen participants are still incarcerated.4 Somepost-release models discussed in this brief (such aswork readiness training and transitional jobs) alsoinclude connection to vocational training, but thisusually is an optional component, and the impactshave not been studied separately from the othercomponents of the interventions. Findings onpre-release models indicate that participating4

Reentry Employment Opportunities Research Briefin such programs can lead to higher rates ofpost-release employment (Davis et al. 2013;Lichtenberger 2007; Saylor and Gaes 1997) andlower rates of recidivism (MacKenzie 2006; Aoset al. 2006; Saylor and Gaes 1997) relative tononparticipants, though to date, nearly all impactstudies of pre-release vocational training programshave been quasi-experimental.5 These pre-releaseprograms, however, require significant effort toestablish and maintain, including the need toadapt vocational programming to operate withinthe security protocols of a correctional settingand the importance of support from correctionalleadership (Harer 1995).Most of the available research on employmentfocused programming is on models that offerwork readiness training (through workshops onsuch topics as interview preparation, resume andcover letter creation, and appropriate workplacebehavior) and/or job search assistance (throughinstruction on effective job search strategiesand individualized support with job applicationsand job placement). Because many interventionsinclude both approaches, these models arediscussed together. Relevant research includesmultisite studies of federal grant streams6and smaller studies of specific local programs.7Rigorous evidence on the impacts of theseapproaches focuses on interventions deliveredafter release (to date, pre-release interventionshave only undergone implementation and outcomeevaluations).8 Implementation of these modelshas been well studied, with the studies noting theimportance of (1) appropriate targeting of thosemost likely to benefit from services, using bothbasic skills assessments and risk assessments(Maguire et al. 2013; D’Amico et al. 2013; Holl etal. 2009); and (2) strong wraparound supports toaddress barriers to employment such as lack ofhousing, unreliable transportation, and substanceuse (Holl and Kolovich 2007; D’Amico et al. 2013;Lattimore et al. 2012; Leshnick et al. 2012; Leufgenet al. 2012; Lindquist et al. 2018). To date, however,impact evaluations of these types of programshave yielded inconsistent evidence on theirSEPTEMBER 2019 mathematica-mpr.comeffectiveness in improving labor market outcomesand reducing recidivism: Four evaluations have documented interventionsthat increase employment rates and/or reducerecidivism. Quasi-experimental evaluationsof Texas’ Project RIO (Finn 1998) and theComALERT Prisoner Reentry Program (Jacobsand Western 2007) both found that theseprograms increased employment rates andreduced recidivism rates. Two other quasiexperimental evaluations, of the Auglaize CountyTransition Program (Miller and Miller 2010)and the Preventing Parolee Crime Program(Zhang et al. 2006), found that both modelsreduced recidivism rates, although neither studymeasured employment outcomes. Four evaluations have yielded inconsistentevidence on the effectiveness of such models.A random assignment evaluation of theEmployment Services for Ex-Offenders (Milkman1985) found that the model reduced recidivismbut had no impact on employment, and a laterreanalysis (Bierens and Carvalho 2011) found thateven the recidivism impacts depended on site andage.9 Similarly, an evaluation of the Serious andViolent Offender Reentry Initiative (Lattimore etal. 2012), based primarily on a quasi-experimentaldesign,10 yielded modest reductions in recidivismbut no impacts on employment for the full sample(although adult females did show increasesin employment rates). An evaluation of sevenSecond Chance Act grantees found that programgroup members had higher earnings and rates ofemployment, but more arrests and convictions,than the control group (D’Amico and Kim 2018). Four evaluations have either found no impactsor detrimental impacts. The experimentalComprehensive Employment and Training ActQualified Probationer Evaluation (Andersonand Schumacker 1986) found no impact onrecidivism and did not measure employmentoutcomes. A quasi-experimental evaluation ofProject Greenlight (Wilson and Davis 2006) foundthat the program increased recidivism rates,although the study did not measure employment5

Reentry Employment Opportunities Research Briefoutcomes. Random assignment evaluations ofthe Reintegration of Ex-Offenders program(Wiegand and Sussell 2015) and an employmentfocused reentry program in Southern California(Farabee et al. 2014) found no impacts onemployment or recidivism.Overall, then, most employment-focused approachesdo not consistently demonstrate evidence of longterm effectiveness at improving employment outcomes and/or reducing justice system involvement.The exception is vocational training, which to datehas primarily been evaluated as a pre-release intervention, and therefore can be challenging to implement, mostly because doing so can be difficult in acorrectional setting. Training for specific occupationsmay be a promising post-release intervention givenits effectiveness as a pre-release strategy. In addition,growing evidence indicates that low-income populations more generally can improve their employment and earnings through approaches designed topromote longer-term connection to stable employment in specific growth fields. These approachesinclude registered apprenticeship (Hollenbeck andHuang 2014; Reed et al. 2012), career pathways (Feinand Hamadyk 2018; Martinson et al. 2018; Peck etal. 2018), and sector strategies (Anderson et al. 2017;Betesh et al. 2017; Copson et al. 2016; Hendra et al.2016; Maguire et al. 2010; Michaelides et al. 2015;Zeidenberg et al. 2010). Many of the REO granteesoffer these types of employment services: 74 offercareer pathways, 72 offer work-based learning, and42 offer Registered Apprenticeship.Cognitive-behavioral therapyA broader evidence base existson the effectiveness of cognitivebehavioral therapy (CBT) insupporting successful reentry forjustice-involved adults. CBT programstrain participants reentering society to monitorand adapt their thinking so they can identify andcorrect destructive thinking and behavior, includingcriminal thinking (Milkman and Wanberg 2007).This approach has sometimes been implementedas a component of the employment-focusedSEPTEMBER 2019 mathematica-mpr.comprogramming discussed above. For example, onestudy (Gosse 2013) examined the specific impactof CBT on participants in the Serious and ViolentOffender Reentry Initiative detailed earlier and foundthat people who received CBT training on reducingcriminal attitudes had lower rates of rearrest.Otherwise, most of the employment-focused studiesdescribed earlier did not examine the impact of CBTspecifically—nor did they study whether the CBTmodels used were implemented with the appropriatedosage and content.11 This latter issue is importantbecause implementation studies of CBT modelsunderscore the importance of rigorous staff trainingand staff retention to ensure consistent delivery ofCBT (Barnes et al. 2017; Miller et al. 2017; Miller andMiller 2016; Duwe and Clark 2015), as well as thechallenges of delivering these interventions, giventhe importance of both structure and sequencing ofthese curricula to ensure fidelity of implementation.Impact studies on CBT approaches show more consistent findings on their effectiveness at reducingrecidivism than those for employment-focused interventions. Three meta-analyses on CBT approacheswith justice-involved populations have found thatCBT interventions reduce recidivism (Aos and Drake2013; Lipsey et al. 2007; Landenberger and Lipsey2006). Similarly, studies on specific CBT models findthat, in general, these approaches reduce recidivism: The Choosing to Think, Thinking to Choosemodel, designed to complement intensiveprobation supervision practices for offendersidentified as high risk, emphasizes angermanagement, responding to stressful situations,managing criminal justice interactions, andinterpersonal relationships. An experimentalstudy of the intervention found that it reducedrecidivism among participants, relative to thecontrol group receiving intensive probationsupervision alone (Barnes et al. 2017). Moral Reconation Therapy is designed to reducerecidivism by increasing moral reasoning. Thismodel has evidence of effectiveness, with a metaanalysis finding that receiving the treatmentreduced recidivism overall, and that impacts were6

Reentry Employment Opportunities Research Briefstrongest for studies with relatively short followup periods and for those that measured recidivismas rearrest, rather than rearrest followed byconviction or reincarceration (Ferguson andWormith 2013; Miller and Miller 2014). Thinking for a Change focuses on social skills,cognitive self-change, and problem solving toreduce criminal thinking and behavior. Quasiexperimental evaluations of the model (Goldenet al. 2006; Lowenkamp et al. 2009) havedemonstrated that it is effective at loweringrecidivism rates relative to comparison groupscreated using propensity score matching. Moving On is an intervention designed for femaleoffenders, covering topics such as self-care,healthy relationships, coping with emotions andharmful self-talk, problem solving, and developingassertiveness. Quasi-experimental evaluationsof Moving On have found that individuals whoparticipated in the program had lower rates ofrecidivism than comparison groups created usingpropensity score matching (Duwe and Clark 2015;Gehring et al. 2010). The exception to this trend of effectivenessat reducing recidivism is MotivationalInterviewing, which has been tested with justiceinvolved populations but was not explicitlydesigned for them. Motivational Interviewing is acounseling approach that tries to change behaviorby helping participants explore and resolveany resistance to change. Two experimentalevaluations of the application of this model tojustice-involved populations show that, althoughit is effective in reducing substance abuse andimproving attitudes, it does not reduce recidivism(Kistenmacher 2008; Woodall et al. 2007).Case managementCase management approaches aimto reduce or eliminate barriers toemployment (such as substance use,lack of transportation, and unstablehousing) through individualized coaching and serviceplanning, as well as through connections to supportiveSEPTEMBER 2019 mathematica-mpr.comservices. As noted earlier, implementation studiesof employment-focused programs have emphasized both the need to connect participants to suchservices and the importance of strong preexistingrelationships between community organizations tohelp with such services, because most employmentprograms cannot provide all these services. A recentsynthesis of the evidence base on these wraparoundservice models shows limited effectiveness in reducing recidivism and improving employment outcomes(Doleac 2019), though this lack of impacts may be afunction of underspecified or insufficiently-intensiveprogram models (Willison 2019).An additional area of research on individual serviceplanning is the Risk-Needs-Responsivity (RNR)framework, in which programs tailor servicesbased on assessments of an individual’s levelof risk for future criminal activity (Bonta andAndrews 2007). RNR—a proposed component ofthe service models of 33 REO grantees—has beenstudied widely in criminology (e.g. Latessa andLowenkamp 2007; Lipsey and Cullen 2007). RNRhas similar characteristics to employment modelsthat aim to tailor services to individual needs andreadiness for employment, and a framework nowexists for merging RNR with employment-specificiterations of service tailoring (Duran et al. 2013).However, this combined approach has yet to beempirically tested. Although these approacheshave been included as components of earlierreferenced employment programs, only threestudies to date have isolated the impact of theseservices specifically. An experimental evaluationof the HealthLink case management programfound that participation neither reduced recidivismnor increased employment rates (Burghardt andNeedels 2004). The other two studies examinedimpacts on recidivism, but not employment. Aquasi-experimental evaluation of Oakland Unite(Gonzalez et al. 2017) found that participating in lifecoaching slightly decreased the likelihood of arrestfor violent offenses, but there were no differences inthe likelihood of arrest for other offenses. A randomassignment evaluation (Palmer et al. 2018) isolatedthe impact of wraparound services specifically,7

Reentry Employment Opportunities Research Brieffinding that emergency housing assistance reducesthe likelihood of rearrest for one year afterassignment to treatment.Evidence on existing programmodels for young adultsArrest rates are highest between the ages of 18 and24, after which point they decline sharply with age(Snyder, Cooper, and Mulako-Wangota 2017), highlighting the need for programming for young adults thatis distinct from programming for adults. Advances inneuroscience have identified ways that young adultsprocess information differently from youth and olderadults, leading to differences in decision making,impulse control, and reasoning (Steinberg 2014).As a result, young adults are more susceptible thanolder adults to impulses that lead to criminal activitybecause their brains are still developing capacities forunderstanding the connections between actions andconsequences (Council of State Governments JusticeCenter 2015). Young adults are also a distinct population from youth: they are more cognitively developed,more vulnerable to peer pressure, and more likely toengage in risky behaviors, and they often seek autonomy from their families (Council of State GovernmentsJustice Center 2015). For these reasons, programsserving young adults often develop approaches thattarget this developmental stage (Stein et al. 2017).In general, young adults are more frequentlydisconnected from education or employment thanolder adults. Further, those in contact with the justicesystem face even greater obstacles to connecting toschool and jobs (Schuchat et al. 2014). When they leaveprison, young adults have spent critical developmentaltime behind bars, potentially inhibiting natural,productive transitions to adulthood (Uggen andWakefield 2005). Incarcerated young adult males areless likely than all adult males ages 18 to 24 to earn ahigh school diploma or GED, secure employment, andget married. In recognition of the many ways youngadults are distinct, many of the approaches describedfor adults—connection to employment, CBT, and casemanagement—have been adapted specifically for thejustice-involved young adult population.SEPTEMBER 2019 mathematica-mpr.comTo date, there is less rigorous evidence of theimpact of reentry interventions that target youngadults, compared to the body of research on adultprograms. This is in part because the numberof programs tailored specifically to the needs ofyoung adults is small, but growing. Among theexisting studies, some do not examine employmentoutcomes in the short term because programsplace young adults in vocational or postsecondaryeducation, and not directly into jobs. Furthermore,employment impacts may be difficult to assess foryoung adults because their employment is moresensitive to cyclical fluctuations in the economythan adult employment (Hossain and Bloom 2015).Employment-focused programmingFew employment and training programs have shown improvementsin employment for justice-involvedyoung adults specifically (see, forexample, Schochet et al. 2006; Abrazaldo et al.2009). Furthermore, there is little research onvocational training programs to engage and prepareyoung adults in the justice system for employment(Visher et al. 2005), and what does exist is primarilydescriptive (Leshnick and Thomason 2015). Many ofthe approaches used by REO grantees were implemented in the three rigorous evaluations of interventions targeting justice-involved young adults: allthree included work-based learning (one of DOL’spriority approaches), one included career pathways,and none included registered apprenticeship orpre-apprenticeship. These interventions generallyshow improvements in recidivism, but only one ofthe three studies examined whether such programming leads to gains in employment and earnings. The Sandhills Vocational Delivery System offeredboth career pathways and work-based learning toincarcerated young adults at two youth custody centers in North Carolina. A random assignment study ofthe program (Lattimore et al. 1990) found that youngadults who participated in the program were significantly less likely to be arrested after release thanthose in the control group, but the researchers didnot examine impacts on employment or earnings.8

Reentry Employment Opportunities Research Brief The Avon Park Youth Academy and STREET Smartprogram serves people ages 16 to 18 who ar

management models for justice-involved adults and young adults and finds: Most prior studies of adult employment reentry programs do not consistently show effects due to variation in program models, implementa-tion quality, and study designs. Reentry programs specifically tailored to young adults often include job training or employ-