Transcription

THE ADLERIAN AND JUNGIAN SCHOOLSA. Individual PsychologyHeinz L. Ansbacher

e-Book 2015 International Psychotherapy InstituteFrom American Handbook of Psychiatry: Volume 1 edited by Silvano AriettiCopyright 1974 by Basic BooksAll Rights ReservedCreated in the United States of America

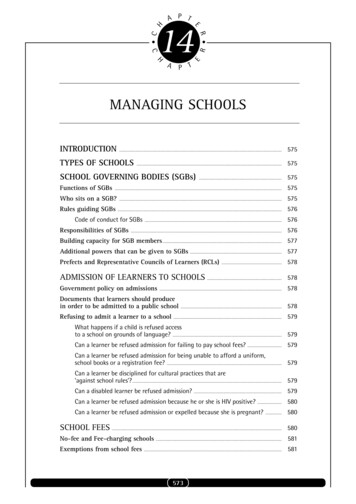

Table of ContentsA. Individual PsychologyAlfred Adler: Development and Systematic PositionPersonality TheoryTheory of PsychopathologyProcess of PsychotherapyIllustrations of the Adlerian ApproachGroup Process and Group ApproachesAdlerian .org4

THE ADLERIAN AND JUNGIAN SCHOOLSA. Individual PsychologyHeinz L. AnsbacherThe most important question of the healthy and the diseased mental life isnot whence? hut, whither? . . . In this whither? the cause is contained.Alfred AdlerThe Adlerian school of psychiatry, represents a unique theory ofpersonality, psychopathology, and psychotherapy and correspondingpractices, which Adler named Individual Psychology.1. It is consistently humanistic, rejecting analogies from physics,chemistry, or animals (except anthropomorphized animalsfrom fables), while stressing man’s striving to overcomedifficulties as an aspect of the general evolutionary principle.2. It is consistently holistic, regarding man as an individual in thesense of being indivisible and unique as well as inextricablyembedded in larger systems of his fellow men.3. It focuses on what is specific to man, his cognitive ability forabstract behavior, for creating fictions, and for anticipatingfuture events.American Handbook of Psychiatry5

4. It regards human creativity with its freedom of choice as decisive,and heredity and environmental factors as subordinated toit. Animals in their natural habitat, instinctually determined,are not subject to mental disorders.5. Man requires values as criteria for choice. While the choice isinvariably in the direction of a goal of success, whatconstitutes success is individually determined.6. Functional mental disorders are based on mistaken schemata ofapperception and mistaken ways of living guided byunsuitable goals of success—mistaken life styles. These arenot in the patient’s awareness but can be inferred from hisactions and their consequences. In psychotherapy thepatient’s cognitive misconceptions and mistaken goals arepointed out to him together with alternatives, thusconfronting him with new choice situations.7. Individual Psychology is pragmatic rather than positivistic,accepting such alternative concepts and assumptions as aretherapeutically valuable and rejecting those associated withpathogenicity. This does not mean that Adler was blind to allthe existing pathologies, only that he preferred to regardthem as avoidable mistakes rather than as something innate.He was deliberately an optimist from the realization thatpessimism is virtually a negation of the work ofpsychotherapy.Adler’s contribution is to have accepted many time-honored and newerphilosophical and scientific humanistic conceptions and to have forged thesewww.freepsychotherapybooks.org6

into an original theory of psychopathology and system of psychotherapy.Alfred Adler: Development and Systematic PositionAlfred Adler was born in 1870, in a suburb of Vienna, received hismedical degree at the University of Vienna in 1895, and subsequentlypracticed medicine there. From 1902 to 1911 he was associated with Freud inthe initial group that became the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. He thendeveloped his own school of Individual Psychology. In the 1920’s he foundeda chain of child guidance centers in Vienna. He began traveling to the UnitedStates in 1926 and settled there in 1935. In 1937 he died on a lecture tour inAberdeen, Scotland. Four biographical accounts of Adler by associates havebeen published,- and one by a detached psychiatrist historian, HenriEllenberger, which is also the best documented.ConstancyAdler was consistently guided by the idea of social progress andmelioration. As a small child he had decided to become a physician “toovercome death” (p. 199). His first publications were on social medicine, withreferences to Rudolf Virchow, the great nineteenth- century research andpublic health physician, liberal, and champion of the poor. As a student he hadbecome interested in socialism and later read before the Freudian circle aAmerican Handbook of Psychiatry7

paper on “The Psychology of Marxism.” He introduced the name IndividualPsychology with Virchow’s definition of individual as “a unified community inwhich all parts cooperate for a common purpose” (p. iv). After World War IAdler condemned the Bolshevik terror, wrote a passionate defense againstthe notion of collective guilt, and, in a handbook on active pacifism,denounced personal power over others as a false ideal to be replaced by oneof social interest. One of his last papers was on “The Progress of Mankind”(pp. 23-28). Adler’s crowning theoretical achievement was the concept ofcommunal feeling (Gemeinschaftsgefiihl), and his outstanding contribution topractice was counseling before a group. In view of such positive orientationtoward the community of man, he had a positive regard for religion as havingalways pointed to “the necessity for brotherly love and the common weal” (p.462), and he appreciated the concept of God as “the dedication of theindividual as well as of society to a goal which rests in the future and whichenhances in the present the driving force toward greatness by strengtheningthe appropriate feelings and emotions” (p. 460).ChangeAdler’s changes were in his theoretical formulations—in the directionaway from a mechanistic-causalistic model of man and toward a humanisticfinalistic model.www.freepsychotherapybooks.org8

When Adler wrote in 1907 about organ inferiority and compensation itwas a step toward an organismic orientation, although he was still causalisticin his expression, and his concept of motivation was essentially one ofhomeostasis through emphasis on the central as against the peripheral andautonomic nervous system. When he introduced in 1908 the concept of theaggression drive he took again a step away from elementarism and towardholism in that this was the result of a confluence of several drives, althoughhe still spoke in terms of a drive psychology. When in 1910 he introduced“inferiority feeling” he brought in the concept of the self with its subjectivityand creativity since the feeling was not in a one-to-one relationship to actualconditions. When in 1910-1912 Adler introduced the “masculine protest” andthe “will to power” these were decisive steps in replacing a causalistic drivepsychology by a finalistic value psychology.When Adler first wrote about communal feeling or social interest,Gemeinschaftsgefiihl, it was almost in opposition to self-interest, a dualismquite foreign to a holistic theory. Only in the late 1920’s did he clarify that thiswas a cognitive function, “an innate potentiality which must be consciouslydeveloped” (p. 134). During this period Adler also introduced the term “lifestyle,” superseding some previous terms, a truly holistic, humanisticconception previously used by the philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey and thesociologist Max Weber.American Handbook of Psychiatry9

WritingsAdler’s psychological writings extend from 1907 until his death in 1937.It is during the second half and increasingly during the last quarter of thisspan that he achieved the sophistication and comprehensiveness on which hispresent-day relevancy is largely based, although the important foundationswere laid during the first period.Most of the books of the second period are available as paperbacks, andarticles after his last book have been collected into a volume that includesalso his essay on religion and a complete bibliography of some 300 titles. Ofhis earlier works, important excerpts are to be found in a book of selectionsfrom his writings. Another volume consists of 28 papers from professionaljournals up to 1920, mainly on psychopathology and psychotherapy.Relationship to FreudFreud formed his original circle in 1902 by inviting four younger men tomeet with him one evening a week to discuss problems of neurosis. One ofthese was Adler, 14 years Freud’s junior. This group developed into theVienna Psychoanalytic Society, and Adler eventually became its president andco-editor of one of its journals—just a year before his resignation in 1911.Freud considered Adler to have been his pupil, which Adler consistentlywww.freepsychotherapybooks.org10

denied. He would admit essentially only that “I profited by his mistakes” (p.358). This position is supported by Ellenberger who states, “Adler seems tohave used Freud largely as an antagonist who helped him . by inspiring himin opposite ways of thought” (p. 627). Ellenberger advises that in order tounderstand Adler the reader “must temporarily put aside all that he learnedabout psychoanalysis and adjust to a quite different way of thinking” (p. 571).The difference is that between a physicalistic-causalistic and a humanisticfinalistic way of thinking.Systematic PositionBecause of the physical contiguity, similarity of subject matter, andFreud’s seniority, Adler’s Individual Psychology was usually classified as avariant of psychoanalytic theory and therapy. In recent years, however, betterclassifications have been introduced. Adler has been designated as “theancestral figure of the ‘new social psychological look’” (p. 115); as amongthose advancing a “pilot” rather than a “robot,” view of man, where man islargely master of his fate (p. 597); as probably the first among the “cognitivechange theorists of psychotherapy” (p. 357), which include Albert Ellis,Adolph Meyer, Fred C. Thorne, George A. Kelly, Rollo May, Viktor Frankl, andO. Hobart Mowrer; as the first among the “third force humanisticpsychologists” (p. ix); as advancing a “fulfillment model” rather than a“conflict model” of personality (pp. 17-19); and as representing theAmerican Handbook of Psychiatry11

philosophy of the Enlightenment. In these various designations Adler isalways found in a group opposed to Freud. In sum they support the statementthat Adler originated a system of psychotherapy in which a mechanisticmedical model of the functional disorders was replaced, not by resortingfurther to the natural sciences, but by aligning itself with the humanities orhuman studies (Geisteswissenschaften) as described by Wilhelm Dilthey andEduard Spranger, while keeping well aware of the somatic chiswhatwehavecalledphenomenological operationalism. On the phenomenological, subjective sideAdler held: “More important than disposition, objective experience andenvironment, is the [individual’s] subjective evaluation of these. Furthermore,this evaluation stands in a certain, often strange relation to reality” (p. 93).Adler was convinced that “a person’s behavior springs from his opinion” (p.182). “Individual Psychology examines the attitudes of an individual” (p. 185).On the operational, objective side Adler’s principle was, “By their fruitsye shall know them” (pp. 64, 283), that is, by overt behavior and itsconsequences. In this respect Individual Psychology comes close tobehaviorism, although the two differ widely in their respective concepts ofhuman nature. In contrast to other subjectivistic approaches andwww.freepsychotherapybooks.org12

psychoanalysis, one will not find in Adlerian literature such terms as real self,primary processes, inner forces, latent states, inner conflict, emotions that theindividual has to “handle,” and many others, because they are like reificationsof abstractions and cannot be operationalized.From this it follows that Individual Psychology is not a depthpsychology, in the sense that something substantive can be found lurkingwithin the individual if you only dig deeply enough. Rather it is a contextpsychology, in the sense that the meaning of a specific form of behavior canbe determined by regarding it in its larger concrete context of which theindividual himself is likely not to be aware. By the same token IndividualPsychology is a concrete and idiographic science, more concerned witharriving at the lawfulness of the individual case than arriving at generalprinciples, which is the emphasis of the nomothetic approaches.Personality TheoryAiming for a humanistic, nonreductionistic, and pragmatically valuablemodel of man and personality theory, Adler borrowed from philosophy andthe other humanities. Thus his conception is in accord with the broad streamof human development found in the other social sciences, in daily life, and inhistory—aiming toward a better life for all, greater freedom, and greaterhumaneness.American Handbook of Psychiatry13

Mans Creativity—Style of LifeAdler presupposes that the human organism is a unified whole that isnot completely determined by heredity and environment, but, once broughtinto existence, develops the capability of influencing and creating events, asevidenced by the cultural products all around us, beginning with language.Adler quoted from Pestalozzi (1746-1827): “The environment molds man, butman molds the environment” (p. 28), a sentence later also used by Karl Marx.Heredity and environment merely supply the raw material that theindividual uses for his purposes. To quote Adler again: “The important thingis not what one is born with, but what use one makes of that equipment” (p.86). To understand this one must assume “still another force: the creativepower of the individual” (p. 87).Adler thus advocated, in fact, a “Third Force” psychology, stressinghuman self- determination, while psychoanalysis essentially stressedheredity, and behaviorism stressed environment. This means in practice thatthe last two look for objective causes in the past to explain behavior, whileAdlerian psychology looks for the individual’s intentions, purposes, or goals,which are of his own creation, to understand behavior.Creativity is the essential part of Adler’s model of man. Its criterion isthe capacity to formulate, consciously or most often unknowingly, a goal ofwww.freepsychotherapybooks.org14

success for one’s endeavors and to develop planful procedures for attainingthe goal, that is, a life plan under which all life processes become a selfconsistent organization, the individual’s style of life.'’ Only in the feebleminded is such purposeful creative power absent.Striving to Overcome: Goal of SuccessA unitary concept of man such as Adler’s requires one overall dynamicprinciple. This Adler derived from the processes of growth and expansion thatare common to all forms of life. Having the capacity to anticipate the futureand having a range of freedom of choice, man develops values and personalideals, that is, mental constructs or fictions, that serve him as criteria ofchoice in his movement through life toward a goal of success. The movementtakes the form of a striving from relative minus to relative plus situations —from inferiority to a goal of superiority.Regarding the question whether the inferiority feeling or the goalstriving is primary, Adler does not give a clear answer. But we hold stronglythat the latter must be primary because where there is no prior conception ofwhat we should and want to be, there can be no inferiority feeling. Most of ushave no inferiority feelings about not being able to speak Chinese because inour environment this is not likely to find inclusion in our goal or image ofsuccess. But everybody’s goal of success includes wanting to be a worthyAmerican Handbook of Psychiatry15

human being. “The sense of worth of the self shall not be allowed to bediminished.” Adler called this “the supreme law” of life (p. 358).Movement from inferiority to superiority is a dialectical conception inwhich Adler was undoubtedly influenced by Nietzsche. Adler found:“Nietzsche’s ‘will to power’ . includes much of our understanding” (p. ix); heconsidered Nietzsche “one of the soaring pillars of our art” (p. 140) andcredited him with “a most penetrating vision” (p. 24). Just as will to powermeant for Nietzsche not domination over others but the dynamics towardself-mastery, self-conquest, self-perfection, so for Adler power meantovercoming difficulties, with personal power over others representing onlyone of a thousand types, the one likely to be found among patients.Social InterestAdler’s most important concept, and the one most specific to him, iscommunal feeling (Gemeinschaftsgefiihl). It is often translated as socialinterest, meaning not an interest in the other as an object for one’s ownpurposes, but “an interest in the interests” of the other. It includes also theconception of being attuned to the universe in which we live. 'Adler’s holistic emphasis saw man not only as an indivisible whole butalso as a part of larger wholes—his family, community, humanity, our planet,the cosmos. Man lives within a social context from which he meets the variouswww.freepsychotherapybooks.org16

life problems of occupation, of sex, and of society in general—all socialproblems.Social interest as a conception is based on the simple assumption thatwe have a natural aptitude for acquiring the skills and understanding to liveunder the conditions into which we are born as human beings. Human nature“includes the possibility of socially affirmative action” (p. 35), a conceptionquite different from conformity and superego, leaving room for socialinnovation, even through rebellion. If such an aptitude were not present inman, how would social living and the creation of the various cultures everhave started? This aptitude, however, needs to be consciously trained anddeveloped. A developed social interest is the criterion for mental health.When the actions belie words of social interest, as is so often the case withneurotics—the “yes-but” of the neurosis— the actions are taken to speaklouder than the words.Social interest is then direction-giving. The direction it gives to action istoward synergy of the personal striving with the striving of others. It is on thesocially useful side, in line with the interests of others. All failures in life, onthe other hand, have in common a striving for a goal of success that has onlypersonal meaning—and thus becomes in the long run unsatisfactory even tothe individual himself.American Handbook of Psychiatry17

Social Interest-Activity TypologyAdler eventually added to his basic dynamics of overcoming a seconddimension, beyond that of social interest, namely, the individual’s degree ofactivity. This led him to a fourfold typology that, however, does not quitecorrespond to the four categories created by the two dimensions. The typesare: high social interest, high activity—the ideally normal; low social interest,high activity—the ruling type, tyrants, delinquents; low social interest, lowactivity—the getting type, expecting from and leaning on others, and theavoiding type, found in neuroses and psychoses; with the category high socialinterest, low activity left unrepresented by a type (pp. 167-169).Approach to Biography and Literary Criticism“Every individual,” Adler" stated, “represents both a unity of personalityand the individual fashioning of that unity. The individual is thus both thepicture and the artist . of his own personality, but as an artist . he is rather aweak . and imperfect human being” (p. 177).This then became Adler’s approach to characters in literary works. Thegreat authors succeed in creating their characters in similar fashion ascharacters in real life “create” themselves. Adler venerated and admired thegreat writers “for their perfect understanding of human nature,” andconsidered any attempt to explain artistic creations by tracing them towww.freepsychotherapybooks.org18

assumed underlying “causes” as being profane and desecrating. Adlerianliterary criticism is concerned with understanding the basic “mistake” in thelife style of the tragic hero, or in the case of an actual biography, perhaps of agreat man, understanding what acts of constructive overcoming of difficultiesbecame decisive. Recent studies along these lines have dealt with Hamlet, thecasket scenes from The Merchant of Venice, Oedipus Rex, Somerset Maugham,and Ben Franklin. There are also numerous earlier studies.Theory of PsychopathologyEveryone lives in a world of his own construction, in accordance withhis own “schema of apperception.” There are great individual variations in theopinion of one’s own situation and of life and the world in general, involvinginnumerable errors. While the “absolute truth” eludes us, we can discernbetween greater and lesser errors. The former are more in accordance with“private sense” (also private intelligence or private logic) and characteristic ofmental disturbance, the latter, with “common sense” (H. S. Sullivan’s“consensus”), an aspect of social interest, and characteristic of mental health(pp. 253-254).It was Kant (1724-1804), with whose writings Adler was wellacquainted, who had originally observed, “The only feature common to allmental disorders is the loss of common sense (sensus communis), and theAmerican Handbook of Psychiatry19

compensatory development of a unique, private sense (sensus privatus).”Interestingly, the Latin communis, in addition to meaning common andgeneral, also means equal and public.The Patient’s CreativityThe patient’s creative process, involving more serious errors than isordinarily the case, has brought him to the predicament in which he findshimself. His “symptoms” are further creations, his own “arrangements” (pp.284- 286) to serve as excuses for not meeting his life problems. They assurehim freedom from responsibility. In trying to convey an excuse they are formsof communication. Since the organism is a unified whole, the autonomicfunctions can become part of these arrangements, the basis forpsychosomatic medicine. In this sense Adler" spoke of organic symptoms as“organ dialect” (p. 223), actually symbolic acts rather than symptoms.In most cases the patient’s circumstances were conducive to mistakenconstructs. As Adler stated, “Every neurotic is partly right” (p. 334). But theAdlerian school does not accept these adverse circumstances as absolutelybinding. Difficulties can be overcome in one way or another. Thus the patientis “right” in that there were “traumatas” and all sorts of “frustrations” in hislife, which can easily be construed as adverse “causes.” But he is only “partlyright” in that he was not obligated to construct his life in the inexpedient waywww.freepsychotherapybooks.org20

in which he did. Others with similar experiences constructed their livesdifferently.Conflict and Emotions Seen Holistically and TeleologicallyOn the basis of its holistic orientation Adlerian theory does notrecognize any internal dualities and antitheses resulting in antitheticalunconscious impulses, or in onslaughts from an unconscious on theconscious. It does not recognize any “intrapersonal” conflicts, only“interpersonal” conflicts arising from the opposition of the patient’s privatesense to the common sense. “Individual Psychology is not the attempt todescribe man in conflict with himself. What it describes is always the sameself in its course of movement which experiences the incongruity of its lifestyle with the social demands” (p. 294).What is often described as “ambivalence” is considered the use ofseemingly antithetical means to arrive at the same end, as a trader sometimesbuys and sometimes sells, but always for the same end of making money. Therelated concepts of doubt and indecision are also arrangements of the patient,serving one unrecognized goal—to maintain the status quo.Emotions are not understood as in conflict with rationality, but in theservice of the hidden purposes of the individual. Thus anxiety supports thecreation of a distance between the person and his tasks of life in order toAmerican Handbook of Psychiatry21

safeguard the self-esteem when there is fear of defeat. “Once a person hasacquired the attitude of running away from the difficulties of life, this may begreatly strengthened . by the addition of anxiety” (p. 276). Lack of socialinterest always being involved in pathology, “the anxious person . . . also feelshimself forced by necessity to think more of himself and has little left over forhis fellow man” (p. 277). Anxiety neurosis and all kinds of phobias serve thepurpose of blocking the way and thus cover up the simple fear of personaldefeat. Actually all neurotic symptoms develop out of an effort to conceal “thehated feeling of inferiority” (p. 304). “The emotions are accentuations of thecharacter traits . . . they are not mysterious phenomena. . . . They appearalways where they serve a purpose corresponding to the life method orguiding line of the individual” (p. 227).The Pampered Life StyleThe predisposing condition for pathology is the pampered style of life.This is more likely to be developed by individuals who as children (1) haveactually been pampered, although it is often found also in those who (2) havebeen unwanted or neglected, or (3) suffered from physical handicaps (organinferiorities) —the three overburdening childhood situations. The pamperedlife style is ultimately the individual’s own creative response to which he is byno means obligated by the situation. The pampered life style is characterizedby leaning on others, always expecting from them, attempting to press themwww.freepsychotherapybooks.org22

into one’s service, evading responsibility, and blaming circumstances or otherpeople for one’s shortcomings, while actually feeling incompetent andinsecure. “The pampered life style” eventually replaced Adler’s original termof “the neurotic disposition.”Also, “We must always suspect an opponent,” according to Adler, “andnote who suffers most because of the patient’s condition. . . . There is alwaysthis element of concealed accusation” (p. 81). This accusation “secures sometriumph or at least allays the fear of defeat,” not in the light of common sense,of course, but in accordance with the patient’s private logic (p. 80).There is then always a degree of self-deception to the extent that thepatient makes himself believe he is not to be blamed because he is notresponsible. This is, of course, a general tendency. But “when the individualhelps it along with his devices, then the entire content of life is permeated bythe reassuring, anesthetizing stream of the life-lie which safeguards the selfesteem” (p. 271). Later Adler most often used the term “self-deception”instead of “life-lie.” This idea was taken up many years later by Sartre in hisconcept of “bad faith,” mauvaise foi.Unity of Mental DisordersIn keeping with a unitary dynamic theory, Adler presented essentially aunitary theory of mental disorders. These are not considered as differentAmerican Handbook of Psychiatry23

illnesses, but the outcomes of mistaken ways of living by discouraged people,people with strong inferiority feelings and unrealistically high and rigidcompensatory goals of personal superiority, and people with insufficientlydeveloped social interest. “What appear as discrete disease entities are onlydifferent symptoms which indicate how one or the other individual considersthat he would dream himself into life without losing the feeling of hispersonal value” (p. 300).“Naturally, anyone, who stands for the unity and uniform structure ofthe psychoneuroses,” Adler observed as early as 1909, “will have to explaineach particular case individually” (p. 301). At the same time Adler recognizedthe commonly observed symptom categories, and in the following we shallgive his views on some of these.Compulsion NeurosisAs Freud used the hysteric as the paradigm of the neurotic, so Adler, infact, considered compulsion neurosis as the prototype of all mental disorders.One of the early Adlerians, Leonhard Seif, had noted that “one could callvirtually any neurosis a compulsion neurosis” (p. 138). The following is asummary description adapted from Adler. (1) A striving for personalsuperiority is diverted into easy channels. (2) This striving for an exclusivesuperiority is encouraged in childhood by excessive pampering. (3)www.freepsychotherapybooks.org24

Compulsion neurosis occurs in the face of actual situations where the dread ofa blow to vanity through failure leads to a hesitating attitude. (4) Thesemeans of relief, once fixed upon, provide the patient with an excuse for failing.(5) The construction of the compulsion neurosis is identical with that of theentire life style. (6) The compulsion does not reside in the compulsive actionsthemselves, but originates in the demands of social living that represent amenace to the patient’s prestige. (7) The life style of the compulsion neuroticadopts all the forms of expression that suit its purpose and rejects the rest.(8) Feelings of guilt of humility, almost always present, are efforts to kill timein order to gain time (pp. 135-137).Even the psychoses share, according to Adler, characteristics of thecompulsion neuroses. “Compulsive symptoms may border on manicdepressive insanity or schizophrenia and resolve themselves into one or theother” (p. 137). “All three groups are variants of a single condition: anextreme superiority complex and [confrontation with social] tasks which callfor more social interest than the patient has” (p. 138).The book by Leon Salzman on The Obsessive Personality fits exceedinglywell within the Adlerian framework. The author considers himself close toRado, Horney, Alexander, Sullivan, Strauss, Goldstein, and Bonime, amongothers.American Handbook of Psychiatry25

Depression, Suicide, and ManiaDepression was for Adler “a remarkable artistic creation (Kunstwerk),only that the awareness of creating is absent and that the patient has growninto this attitude since childhood.” It is actually “the endeavor throughant

Adler was convinced that "a person's behavior springs from his opinion" (p. 182). "Individual Psychology examines the attitudes of an individual" (p. 185). On the operational, objective side Adler's principle was, "By their fruits ye shall know them" (pp. 64, 283), that is, by overt behavior and its consequences.