Transcription

2017-2022 Texas State Health PlanSHCCStatewideHealthCoordinatingCouncilA Proposal for Ensuring High-QualityHealth Care for All Texans

SHCCStatewideHealthCoordinatingCouncilStatewide Health Coordinating CouncilP.O. Box 149347 Austin, Texas 78714-9347Phone: (512) 776-7261Fax: (512) 776-7344SHCC@dshs.state.tx.usNovember 1, 2016The Honorable Greg AbbottOffice of the GovernorP.O. Box 12428Austin, Texas 78711-2428Dear Governor Abbott,The Texas Statewide Health Coordinating Council is pleased to submit to you the 2017-2022 TexasState Health Plan. The Council has chosen to focus this update on primary care and mental healthcare which it feels are very important to our state today and will continue to be important in the nearfuture.Despite recent gains, opportunities for improving Texas’ health care system persist. As such, theCouncil recommends the following strategies for ensuring that Texas’ health care system serves allcitizens in an effective and economical manner:Individual: Improve access by reducing cost-related barriers to care for the most disadvantaged Texans,promote patient health literacy, and advocate cost-effective population health programs.Education system: Ensure adequate educational opportunities exist for aspiring health care providers,especially clinical training sites for physicians, nurses, physician assistants, and others.Health care providers: Incentivize health care professionals to select specialties, employment settings, andgeographic locales that reflect population needs.Health system: Improve quality of health care by encouraging the adoption of delivery and payment systeminnovations, including coordinated and integrated care, health information technologies, and modelsrewarding quality care, such as ACOs.State agencies: Enable increased and improved data collection and analysis that inform the bestimplementation of the above.The Council hopes these are useful to you and other policymakers as you continue to work to improvethe state’s health care system.Sincerely,Ayeez Lalji, D.D.S.Chair, Statewide Health Coordinating CouncilEnclosure

The Texas Statewide Health Coordinating CouncilGubernatorial Appointees RoleAyeez Lalji, D.D.S., ChairHealth care professionalElizabeth J. Protas, P.T., Ph.D., Vice-chairPublic memberCarol Boswell, Ed.D., R.N., C.N.E., A.N.E.F., F.A.A.N.University representativeAndrew D. Crim University representativeLourdes M. Cuellar, M.S., R.Ph.Hospital representativeSalil Deshpande, M.D. HMO representativeElva Concha LeBlanc, Ph.D.Community college representativeMelinda Rodriguez, P.T., D.P.THealth care professionalLarry Safir Public memberCourtney Sherman, D.N.P., R.N., W.H.N.P.-B.C.Nurse representativeD. Bailey Wynne, R.Ph., M.H.A.Public memberShaukat Zakaria Public memberYasser Zeid, M.D.Health care professionalState Agency Members RepresentingLisa Glenn, M.D.Department of Aging and Disability ServicesMike MaplesDepartment of State Health ServicesJimmy Blanton, M.P.Aff.Health and Human Services CommissionStacey Silverman, Ph.D.Texas Higher Education Coordinating Boardiii

For further information concerning this report, please contact:The Texas Statewide Health Coordinating CouncilCenter for Health Statistics – MC 1898Texas Department of State Health ServicesP.O. Box 149347Austin, TX te.tx.us/chs/shcc/This publication is issued by the Texas Department of State Health Services for the Statewide HealthCoordinating Council (SHCC) under the authority of the Texas Health and Safety Code, Chapter 104.Publication #: 25-14865

Organizational Overviewprepares reports on the findingsDesignates health care delivery sites wheremid-level providers can practice limitedprescriptive authorityProvides resources for primary care providersseeking collaborative practice opportunitiesthrough a clearinghouse programThe following is a description of the organizationsthat were instrumental in the development andproduction of this report.The Texas Statewide Health Coordinating CouncilIn accordance with Chapters 104 and 105 of theTexas Health and Safety Code (HSC), the purpose ofthe Statewide Health Coordinating Council (SHCC)is to ensure health care services and facilities areavailable to all citizens through the development ofhealth planning activities. The SHCC is a 17-membercouncil, with 13 members appointed by the governorand four members representing the Departmentof Aging and Disability Services, the Departmentof State Health Services (DSHS), the Health andHuman Services Commission (HHSC), and the TexasHigher Education Coordinating Board (THECB).The SHCC meets quarterly and governs the HealthProfessions Resource Center (HPRC), the TexasCenter for Nursing Workforce Studies (TCNWS),and the Texas Center for Nursing Workforce StudiesAdvisory Committee (TCNWSAC). Informationon the SHCC is available at the following tional information on the HPRC, its data,and its reports can be found at http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/chs/hprc/.The Texas Center for Nursing Workforce StudiesThe TCNWS was established and serves as a resourcefor data and research on the nursing workforce inTexas. The TCNWS is charged to collect and analyzedata and publish reports related to educational andemployment trends of nursing professionals, thesupply and demand of nursing professionals, nursingworkforce demographics, migration of nursingprofessionals, and other issues concerning nursingprofessionals in Texas as determined necessary by theTCNWSAC and the SHCC.The TCNWS collaborates and coordinates withother organizations that gather and use nursingworkforce data to avoid duplication of efforts ingathering data, to avoid overloading employers andeducators with completing a large number of duplicatesurveys, to share resources in the development andimplementation of studies, and to establish bettersources of data and methods for providing data tolegislators, policymakers, and key stakeholders. TheTCNWS is currently working on several statewidestudies that will provide current and pertinent supplyand demand trends of the nursing workforce in Texas.For more information about the TCNWS and accessto its reports visit: http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/chs/cnws/.As part of its duties under Chapter 104 and 105 ofthe Texas HSC, the SHCC directs the developmentof the State Health Plan and its updates. Thesedocuments, published in November of evennumbered years, identify major statewide healthconcerns, the availability and use of the state’s healthresources, and future health service, informationtechnology, and facility needs of the state.The Health Professions Resource CenterThe HPRC collects and analyzes data pertainingto educational and employment trends for healthprofessions in Texas, with particular interest in healthprofessions demonstrating an acute shortage.The Texas Center for Health StatisticsIt is the mission of the HPRC to be the primarysource of health care workforce information in theState of Texas. To accomplish this mission, the HPRC:Collects, analyzes, and disseminates dataconcerning the supply trends, geographicdistribution, and demographics of healthcare professionalsStudies health care workforce issues andThe Texas Center for Health Statistics (CHS)provides managerial oversight and administrativesupport to the HPRC and the TCNWS.vThe CHS was established to provide a convenientaccess point for health-related data for Texas. TheCHS conducts much of DSHS’ collection, analysis,and dissemination of health-related information used

to evaluate and improve public health in Texas. CHSdoes so by:Evaluating existing data systems foravailability, quality, and quantity;Defining data needs and analytic approachesfor addressing these needs;Adopting standards for data collection,summarization, and dissemination;Coordinating, integrating, and providingaccess to data;Providing guidance and education on the useand application of data;Providing data analysis and interpretation;andInitiating participation of stakeholders whileensuring the privacy of the citizens of Texas.Health-related data reports and other informationproduced through the CHS are available at thefollowing website: http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/chs/.vi

Table of ContentsThe Texas Statewide Health Coordinating Council Organizational Overview Table of Contents Executive Summary Data & Sources Access to Care Defining Access Populations with Poor Access Texas Populations with Poor Access Strategies for Improving Access Improving Quality In Health Care The Case for ACOs Forming an ACO Quality Reporting Health Literacy Educational Pipeline of Health Providers Supply and Demand of Health Professionals in the State Interprofessional Collaboration in Texas Improving the Training of Health Professionals Practice Choices of Health Professionals SHCCiiivviiixxiii3344613131315162121242527A Vision for Primary Care in the State of Texas The Need for Primary Care 3133Evidence for Primary Care Supply of and Demand for the Primary Care Workforce Policy Considerations 333334Primary Care and the Patient-Centered Medical Home Role of the Patient-Centered Medical Home Policy Considerations Primary Care Physicians vii37373740

Policy Considerations 40Physician Assistants in Primary Care 44Competencies and Roles Physician Assistant Contributions to Efficacy and Efficiency Policy Considerations Military Veterans as PAs 44454647Advanced Practice Nurses in Primary Care 48Competencies and Roles APN Contributions to Efficacy and Efficiency Policy Considerations 484950Pharmacists as Providers 52Competencies and Roles Pharmacist Contributions to Efficacy and Efficiency Pharmacist Roles in Patient Care Community Health Workers 52535456Competencies and Roles CHW Contributions to Efficacy and Efficiency Policy Considerations 565758Review of Primary Care Policy Recommendations Transforming Texas’ Mental Health Care System The Mental Health Delivery System 606163Innovation in Mental Health Delivery Delivery and Payment Models Moving Forward 636566The Mental Health Workforce Shortage 70Texas’ Need for Mental Health Services Texas’ Mental Health Workforce 7171Review of Mental Health Policy Recommendations References List of Acronyms Appendix 828599A0viii

Executive Summaryshortages existing in the state, and addresses multiplepolicy options used to address these shortages. Thefourth chapter, A Vision for Primary Care in the Stateof Texas, details how a robust and accessible primarycare system contributes to improved population healthand cost efficiency. The fifth chapter, TransformingTexas’ Mental Health Care System, considers neededchanges in the organization of the system, how itengages patients, and the challenges posed by themental health workforce shortage. In summary, thesetopics are essential to the SHCC’s vision of a Texas inwhich all are able to achieve their maximum healthpotential. By outlining strategies to improve primarycare and mental health in the state, the SHCCchallenges policymakers, health care administrators,providers, and all Texans to embrace change and worktogether to improve the health of Texans.On a biennial basis, the Texas Statewide HealthCoordinating Council (SHCC) directs and approvesthe development of the Texas State Health Plan orits updates. This plan, following the legislativelydetermined purpose of the SHCC, seeks to ensurethat the State of Texas implements appropriate healthplanning activities and that health care services areprovided in a cost-effective manner throughout thestate. With drastic changes being introduced to healthcare payment and delivery systems nationwide andthroughout Texas, the 2017-2022 Texas State HealthPlan provides guidance on how these changes can beimplemented in a manner consistent with the goalof having a high quality, efficient health system thatserves the needs of all Texans. Specifically, this planidentifies challenges in ensuring that a populationas large and diverse as Texas’ has access to the healthcare system, that health care services are provided inan efficient and orderly manner, and that an amplehealth care workforce exists to provide these services.Additionally, the SHCC revisits the pressing need forrobust primary care and mental health systems in thestate, concerns first raised in its 2015-2016 Updateto the Texas State Health Plan. In response to thesechallenges, the current plan offers numerous strategiesto improve the efficiency of our health care deliverysystem, address shortcomings in our payment system,produce more health care providers in critical areasof need, and heighten patient satisfaction with thehealth care system.Improving Texans’ Access to CareThe ability of individuals to access care when theyneed it is central to the successful performance ofhealth care systems at local, state, and national levels.Generally, access is conceptualized as the abilityof the health care system to meet the population’sdemand for services or the ability of the populationto shoulder the economic costs associated with care.However, definitions of access should also considerhow social, cultural, and linguistic norms may affectpatient interaction with the health care system, howsatisfied or comfortable the patient is with their healthcare interactions, and the extent to which patients areable to navigate the health system. Using this broadformulation of access, multiple populations definedby age, race/ethnicity, and geographic location,among other factors, can be said to experienceinadequate access to care. The plan describes threebroad strategies available to address the gaps in accessto care identified above: improving rates of insurancecoverage; increasing the availability of health careprofessionals, facilities, and services; and a reductionin the social barriers to care.The 2017-2022 Texas State Health Plan isorganized into five chapters highlighting importantareas where improvement is needed. ImprovingTexans’ Access to Care, the plan’s first chapter, detailsthe populations for whom access to care is an issue inTexas and considers methods for improving providerparticipation in ensuring access and expandingthe distribution of providers throughout the state.The second chapter, Improving Quality in HealthCare, describes the potential for accountable careorganizations (ACOs) to improve quality of care, aswell as the necessity of having a population that ishealth literate and invested in health outcomes. Thethird chapter, Widening the Education Pipeline forthe Health Professions, establishes a baseline for thesize of the health care workforce, describes relativeImproving Quality in Health CareThe Institute of Medicine has defined qualityhealth care as “safe, effective, patient-centered, timely,efficient and equitable.” Likewise, the federal Agencyfor Healthcare Research and Quality described qualityix

as “doing the right thing for the right patient, at theright time, in the right way to achieve the best possibleresults”. The SHCC believes that improvement inhealth care quality must be accompanied by effortsto control costs, which will require a move awayfrom traditional fee-for-service models of care andtoward value-based payment systems. Among theavailable options, the ACO offers promising resultsfor the reorganization of payment and deliverysystems in a way that reduces costs and improvesquality. Additionally, the SHCC recommends thecontinued adoption of data collection and reportingmechanisms that allow health systems to constantlymeasure and improve their quality and outcomes.Finally, the SHCC supports partnerships betweenproviders and health educators to empower Texans tobetter understand and utilize the state’s health caresystem.of health professionals and to implement programsthat embrace innovation and ensure the state’s futurehealth professionals are equipped to deliver care in thebest, most cost-effective manner possible. Specifically,the State of Texas should:Ensure the state’s physician workforce is ableto meet Texans’ needs through the continuedsupport of medical and graduate medicaleducation.Identify and implement strategies to increasethe number of clinical training sites available tonurses, physician assistants, and other health careprofessions.Incentivize health care professionals to selectspecialties, employment settings, and geographiclocales that reflect the needs of the state.Improve data collection across state agenciesand develop complex, multidisciplinary healthworkforce projections.Widening the Education Pipeline for the Health ProfessionsA Vision for Primary Care in the State of TexasOne key to ensuring that health care services andfacilities are available to all Texans in an orderly andeconomical manner is to ensure that the state has a welltrained and ample workforce of health professionals.Such a workforce should be large enough to meetthe needs of its clients, and also must be availableacross the state, in geographically disparate areas. Asthe population of the state continues to grow, so toomust the state’s investment in the training of healthprofessionals at all levels. Generally, Texas has fewerpractitioners per capita than the national average inall of the key health professions. Health professionsdata show that rural and border areas have farfewer practitioners per capita than do metropolitanand non-border areas, respectively. These data alsodemonstrate that large proportions of providers inmany professions are older and expected to retire in thenext decade or so. Finally, these data indicate that thehealth care workforce is far from being representativeof the general Texas population with respect to race/ethnicity. The state should continue to research andinvest in programs that ensure Texans have easy accessto care, regardless of the region of the state in whichthey live, that the state’s future health care workforce isof sufficient size and well-prepared to serve the needsof the state, and that Texans have access to providerswho provide linguistically and culturally competentcare. An essential component of achieving thesegoals will be for the state to invest in the educationAccess to and appropriate use of primary careproduces better quality health care, better health,greater equity, and lower cost for individuals andpopulations. Moreover, health systems orientedtowards primary care serve to lower barriers topatient access, improve care coordination betweenproviders, and encourage responsible patient choicesin care-seeking behavior. Despite these benefits, theInstitute of Medicine has stated that the U.S. has notadequately invested in a robust primary care system.Given the positive impacts associated with greaterintegration of primary care services, the SHCC hasidentified several policy options that would improveTexas’ primary care system.Increased patient utilization of care, changingdemographics, and increases in chronic disease burdenentail the need to increase the number of primarycare providers, including physicians, advancedpractice nurses, physician assistants, pharmacists, andcommunity health workers. The number of primarycare physicians should be increased through thesupport of primary care medical schools and graduatemedical education slots, improved recruitment ofstudents interested in practicing primary care, and theexpansion of incentives that aid in the recruitmentand retention of primary care physicians.The desired improvements in the cost-effectivenessx

and efficiency of the health care system will necessitatechanges in the delivery and reimbursement of care. Acommon element for accountable care organizationsand other innovative delivery and payment structuresis the expansion of interdisciplinary team-basedcare, which is associated with fewer communicationproblems between providers, improved care,and greater patient satisfaction. The widespreadimplementation of patient-centered medical homes,accountable care organizations, and other innovativecare models will require ongoing evaluation of bestpractices and among which populations they may bemost successful.Transforming Texas’ Mental Health Care SystemRecent studies, national and specific to Texas,have established the need for the transformation ofthe mental health care system to better meet patientneeds. As with primary care, the SHCC has identifiedseveral strategies that address Texas’ needs.Team-based, collaborative, and coordinatedcare is an essential component of transformingthe mental health care system. Task-shifting, theadoption of disruptive innovations, the use of bestbuy interventions, and efforts aimed at modifyingindividual behavior are all potential elements inaffecting improved mental health care delivery. Thepatient-centered medical home, health homes, andaccountable care organizations may provide betterdelivery of care while addressing issues with thecurrent mental health care reimbursement system.The successful incorporation of peer support providersinto the mental health care system will require theirincorporation into billing/payment systems.In order for Texas to have a stable, productive,and efficient mental health care system, heightenedefforts at recruiting and retaining mental health careproviders are a necessity. The SHCC, in responseto House Bill 1023 (83rd Legislature), providedseveral recommendations aimed at expanding thestate’s educational capacity to produce mental healthpractitioners, increasing incentives for students andpractitioners to choose mental health fields, andimproving the distribution and diversity of mentalhealth practitioners.xi

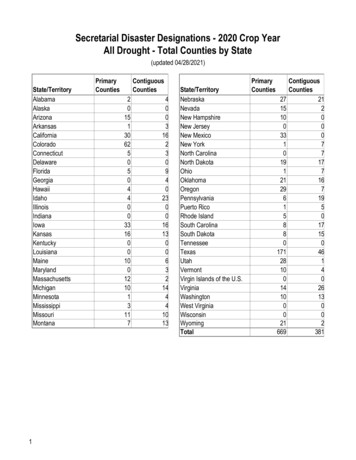

Data & SourcesThe Texas workforce data included in thisdocument is collected by various Texas licensingboards and processed by the HPRC under thedirection of the SHCC as dictated by the Texas HSCChapters 104 and 105. All reported data representthe licensed health professionals actively practicingin Texas. Inactive or retired licensed professionalswere excluded, except where noted. Texas populationdata were obtained from the Texas State Data Centerpopulation projections released in 2014.Please note that the various licensing boards differon how they collect address information. If available,the county totals for each profession are based onthe practice address from licensure data, and fromthe mailing/residence address if the practice addressis not available. Therefore, when the mailing/residence address is used, the county supply totalsmay not accurately reflect the actual number of healthprofessionals working in a county since a provider maylive in one county but practice in another. In 2007,the 80th Texas Legislature passed Senate Bill (SB) 29mandating the collection of a minimum dataset ofinformation on health professionals including morecomplete data on practice addresses. Licensure boardsvary in the extent to which they have implementedthe minimum dataset.Supply ratios are calculated by dividing the numberof providers in a given profession by the populationof the area being evaluated, and multiplying thatnumber by 100,000. This results in a ratio of providersper 100,000 population that can be used to compareareas with different population sizes and over time.The definitions of metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties were obtained from the UnitedStates (U.S.) Office of Management and Budget. The32 counties within 100 kilometers of the U.S.-Mexicoborder are designated as border counties as defined bythe “La Paz Agreement” (La Paz Agreement, 1983).xiii

Improving Texans’Health Care AccessKey Policy RecommendationsSupport programs that seek to improve the population’s access tocare, especially those that promote primary and preventive care.Address barriers that limit health care professionals ability to servepatients of all income levels.Identify and support evidence-based, prevention-orientedpopulation health approaches toward chronic disease.1

Access to CareDefining AccessThroughout much of Texas, and the nation as awhole, access to care is restricted by the availabilityof providers. Areas without sufficient provideravailability may receive a federal designation as ahealth professional shortage area. This definition ofaccess relies on the idea that those who need healthcare can access the system if there is an adequate supplyof services, measured by the number of physicians,hospital beds, or some other metric (Guilford, et al.,2002). Yet these geographic designations do not fullyreflect the multifaceted concept that is access to care.Indeed, the Institute of Medicine has proposed thedefinition of access as “timely use of personal healthcare services to achieve the best possible outcomes”(Pandhi, et al., 2012). In addition to the availabilityof providers, this definition adds components oftimeliness and quality, the latter in the form ofpositive outcomes. Likewise, another proposeddefinition of access is “fair access to consistently highquality, prompt and accessible services right across thecountry” (Guilford, et al., 2002). This introduces theimportant consideration of equity. This considerationis important given estimates that 30 percent of directmedical expenditures can be attributed to healthdisparities that create a less healthy population (Shi,et al, 2013) and that disparities are associated withbarriers to accessing care.care. This may refer to directly incurred costsor those associated with insurance coverage,including premiums, deductibles, etc.Availability – the level of fit between thepatient’s health care needs and the ability ofthe system to fit these needs. For example,availability is a measure of the nearness andcapacity of clinicians and clinical facilities.Acceptability – the ability of patients tointeract with the health care system in lightof social, cultural, and linguistic norms,among others that may impede utilization.Appropriateness – the extent to whichthe services available fit the needs of theclient. On the one hand, appropriatenessmay refer to the patient’s level of comfortwith the organization of the health system,such as procedures necessary to garner anappointment, available office hours, etc. Onthe other hand, this category may also includecare meeting the patient’s expectations withrespect to elements such as timeliness, theamount of time spent developing a diagnosisand treatment plan, and the technical andinterpersonal quality of the services rendered.Approachability – the extent to which peoplewith health care needs are able to identifythe appropriate services available, are awareof how to reach them, and recognize thepotential impact on their health.Of note, four of the five categories listed above areunrelated to financial capacity of the individual to payfor health care. While financial barriers to access areimportant and associated with the presence of nonfinancial barriers, it is worthwhile to note that 66.8percent of US adults reported non-financial barriersto care, a rate higher than those reporting financialbarriers. Moreover, 71 percent of Medicaid patientsand 49 percent of Medicare patients reported nonfinancial barriers to accessing care (Levesque, Harris,and Russell, 2013).The ability of individuals to access care when theyneed it is central to the successful performance ofhealth care systems at local, state, and national levels.Simplistically, access may be considered the easewith which consumers and communities are able touse appropriate services in proportion to their needs(Levesque, Harris, and Russell, 2013). Access can thenbe considered in economic or other terms, such asthe time required to utilize health care services, traveldistance to services, familiarity with the health systemand providers, and other considerations (Guilford,et al., 2002; Pandhi, et al., 2012; Levesque, Harris,and Russell, 2013). Both Kullgren et al. (2012) andLevesque, Harris, and Russell (2013) have proposedsimilar methods for categorizing potential barriers toaccess. Synthesized, they are as follows:Affordability – the ability of the patient topay the economic costs associated with healthWith respect to availability, one of the mainbarriers that exists to access is a lack of specialists andsubspecialists present in low-income and rural areas.For example, one survey found that 91 percent ofcommunity health centers struggled to find adequateoff-site subspecialty care for their uninsured patients(Neuhausen, et al., 2012).3

A major concern regarding acceptability is the extentto which patients are able to receive informationand instructions in their preferred language. Oftenlinguistically-based barriers can result in the delay oreven denial of services, challenges with medicationmanagement, and the underutilization of preventiveservices (Au, Taylor, & Gold, 2009). Of note, theNational Committee for Quality Assurance and theJoint Commission on the Accreditation of HealthcareOrganizations are beginning to recognize the role thatlanguage services play in the production of qualityhealth care. Clinical staff may need training onwhen to request a medical interpreter, as unqualifiedinterpreters may lead to medical errors and poorpatient understanding and adherence (Au, Taylor, &Gold, 2009).one chronic disease (Kullgren, et al., 2012, AHRQ,2015). Indeed, Kenney reports that access to caredeclined in all adult populations from 2000 to 2010with the most dramatic declines present in uninsuredpopulations (2012). Thus it comes as no surprise thatuninsuredness is associated with foregoing needed carebecause of cost, not having a usual source of care, notreceiving recommended screening activities, high-riskadults not getting checkups in the past two years, andpatients with diabetes not receiving recommendeddiabetes care (Radley & Schoen, 2012).According to the Institute of Medicine, uninsuredpregnant women receive fewer prenatal care servicesthan women with insurance and are more likely tohave poor birth outcomes, including low-birth weightand prematurity. Following pregnancy, women needon

P.O. Box 149347 Austin, Texas 78714-9347. Fax: (512) 776-7344. Statewide Health Coordinating Council. . Ph.D. Community college representative Melinda Rodriguez, P.T., D.P.T Health care professional . Primary Care and the Patient-Centered Medical Home 37 Role of the Patient-Centered Medical Home 37