Transcription

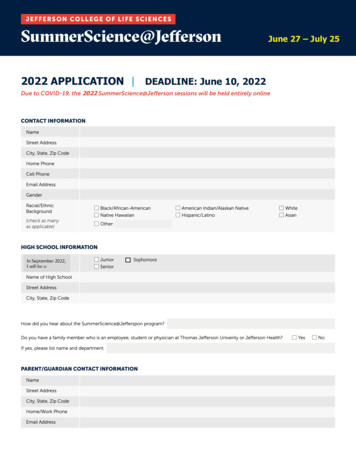

1 MESALC NEWSLETTERVolume 7, Issue 1 Spring 2018Jefferson: Education as the Antidoteto “Failed Revolutions” . 1J-Term in Kerala: India in GlobalHistory . 3Jefferson:Education as the Antidote to“Failed Revolutions”Welcome to MESALC: New HindiInstructor . 4New Fall 2018 Courses . 5New Faculty Publications . 6Sajedeh Hosseini: Serving as a TA atMr. Jefferson’s School Brightenedmy Days . 8Mehr Farooqi: A Night of Ghazalsand Sufi Kalam . 9Janaezjah Ryder: From Pune toUVA . 10Hanadi Al-Samman: The Aestheticsof Trauma . 11Aenon Moose’s Speech at 2017MESALC Graduation Ceremony . 12Thomas Jefferson Makes his Debuton Arabic TV . 13Envisioning 21st Century MiddleEast & South Asian Studies . 14“The Arab Spring” now seems to many but a distantmemory, a chimera, a false hope, one too painful to remember,revisit, or even study seriously. Mr. Jefferson would beg todiffer.Jefferson’s words on revolution did not stop with hiscrafting of America’s Declaration of Independence. During thehalf century that followed, Jefferson avidly followed andcommented upon revolutionary developments around the world.While Ambassador to France, Jefferson warmly supported theemerging French Revolution, counseling moderation andadvising the Marquis de Lafayette on France’s Declaration of theRights of Man.As France’s revolution struggled, Jefferson as USSecretary of State offered encouragement to French friends andintellectuals. To the Duchess d’Auville, on April 2, 1790,Jefferson wrote, “You have had some checks, some horrors sinceI left you; but the way to heaven, you know, has always beensaid to be strewed with thorns.” On the same day, he reasoned toLafayette that, "We are not to expect to be translated fromdespotism to liberty in a feather-bed."

2 MESALC NEWSLETTERE DU C AT I ON AS ANT I D OT Eco n ti n u ed fr o m p a ge 1Jefferson eventually cameto deplore the excesses ofrevolutions gone wrong, theexecutions of innocents and“Robespierre’s atrocities.” Yet lutionary intellectual FrancoisD’Ivernois, Jefferson wrote in1795 of how “unfortunate” it wasthat the “efforts of mankind torecover the freedom of which theyhave been so long deprived, willbe accompanied with violence,with errors, and even withcrimes.” Yet “while we weep overthe means, we must pray for theend."(Of ironic note to us,D’Ivernois within that samecorrespondenceofferedtoAmerica the science faculty of thethen destroyed College at Geneva.TheideafiredJefferson’simagination, thirty years beforethe opening of UVA.)Despite the brutal turns ofthe French revolution, Jeffersonstill believed that America’sexample could be emulatedelsewhere. Impressed by TenchCoxe’s accounts of the Dutch(Batavian) revolution, Jefferson onJune 1st,1795 responded that this“proves there is a god in heaven,and that he will not slumberwithout end on the iniquities oftyrants.” Even more effusively,Jefferson opined that “this ball ofliberty, I believe most piously, isnow so well in motion that it willroll round the globe, at least theenlightened part of it, for light &liberty go together.”Yet Jefferson saw enoughrevolutionary failures to promptextended reflection upon why somerevolutions succeeded and othersfailed. Variables pondered includeleadership quality, economics,social divisions, and the military.On the latter, Jefferson wrote toEdmund Rutledge in 1788 that arevolution’s outcome “will dependentirely on the disposition of thearmy whether it issue in liberty ordespotism." Were he alive today,Jefferson would recognize whatwent down in Egypt on the eve ofJuly 4th, 2013.Jefferson’s data base wasn’tjust Europe. Amid an extraordinaryexchange with the celebratedSwiss-French revolutionary womanof letters, Madame de StaëlHolstein, Jefferson assessed theprospects for “liberty” in SouthAmerica. For Jefferson, the “realdifficulties” there were not so muchkeeping external powers (theSpanish) at bay, but “how to silenceand disarm the schisms amongthemselves. [I]n all those countries,the most inveterate divisions havearisen” – among “casts” and “rivalleaders” and families.(Libyaanyone?)Even as they might attain“independence”fromEurope,Jefferson’s view of the “horizons”for liberty was low, given how the“whole Southern continent is sunkin the deepest ignorance andbigotry” which will “render themincapableofformingandmaintaining a free government.”Jeffersonparticularlydespaired at the power of variousclergies over the minds of illiteratecitizens. As much as the heartmight wish otherwise, for Jefferson,it was much as the heart might wishotherwise, for Jefferson, it waspersonally “excruciating to believethat all will end in militarydespotisms.” (To those who stillbelieve in the Arab Spring’soriginal aims, Jefferson can “feelyour pain.”)For Jefferson, the key toimproving the chances forrevolutionarystrugglesforliberty to survive was notexternal armed intervention, oreconomic aid, but education. Tothat end, that “holy cause”Jefferson turned to his last greatrevolutionary idea – publicsupported education and thefounding of the University ofVirginia. As TJ wrote in 1816,“Enlighten the people generally,and tyranny and oppressions ofbody and mind will vanish like evilspirits at the dawn of day.” ToJefferson then, the best antidote forfailed revolutions for liberty iseducation.Continue readingon page 7.

3 MESALC NEWSLETTERJ-Term in KeralaINDIA IN GLOBAL HISTORYEnj o yi n g W el co me Di n n er at Ho tel i n Ko c h i.We began this year (2018) with the first JTerm in the southern state of Kerala, India. Thecourse lead by Mehr Farooqi and Richard Cohenis designed to whet student’s interest in important,historical global networks that are generallybypassed in curricula because they are buried inhistory. The course taps into the economiccultural historical elements of the spice and cottontextile trade and its profound impact on crossIndian Ocean trade with the Middle East, EastAfrica, Europe and East Asia. The first Europeanto reach India was the Portuguese sailor, Vasco daGama (1498), landing at the coastal town ofKozhikode (Calicut). Kerala is the mostheterogeneous Indian state, having significantminority Muslim and Christian populations. Thepredominant language is Malayalam, followed byEnglish. Kerala has the highest literacy rate inIndia (94%). Its dramatic dance arts, such asKathakali, Kutiyattam and Theyyam are worldfamous. Readings in history and literaturecomplemented the site visits.The State of Kerala, India is unique notonly in its geographical design, but also in theculture of its people. The cities of Kozhikode andKochi are the two main entrepôts through whichthe spice trade was initiated and prospered overcenturies. Merchants from the Middle East, SwahiliCoast (East Africa) and Southern Europe establishedsettlements in Kerala. The Jewish connection withKerala started in 573 BCE. Herodotus noted thatgoods brought by Arabs from Kerala were sold tothe Jews at Aden. Arabs intermarried with localpeople, resulting in formation of the MuslimMappila community, becoming central to the transIndian Ocean trade networks. Student discovery ofthe history of these contacts will profoundly changetheir understanding of the origins and implicationsof ethnic, cultural and religious heterogeneity, aswell as the diachronic fluctuations of globalization.The first group of nine students drawn from acrossUVA described their experience as particularlyenriching. “The course leaders didn't stop teachingwhenever our day's class time was up. Instead, theymade sure to talk to us about each hands-onexperience we had to enrich our knowledge about it.They also were sure to tie a lot of our activities backinto course material.”Map o f t he Si l k Ro ad . T he sp ice trad e wa sma i nl y alo n g t he wa ter r o ut e s (b l u e).MEHR FAROOQI

4 MESALC NEWSLETTERWelcome to MESALC!NEW HINDI INSTRUCTORAb d ul Na sirMy journey as a student and Hindi-Urdusecond language instructor starts at Mussoorie, avery small and beautiful city at the foothills ofIndian Himalayas. At the University of Virginia, Ifind myself happier than ever before. It is almostlike a dream come true.I earned my M.A. in Hindi Literature andLinguistics from Hemwati Nandan BahugunaGarhwal University, Srinagar India in 2012. Thisoffered me the opportunity to better understandHindi prose, poetry, and drama as well as thehistory of the language itself. I completed myB.A. in Urdu Literature from Jamia Urdu Aligarh,India in 2009. I also have received a B.S. fromChaudhri Charan Singh University India in 2001.The considerable amount of time I had spent ascode writer in different computer languages,helped me feel more comfortable in understandingmodern day technologies.For more than nine years from 2007 to2016, I taught Hindi and Urdu at all levels as asecond language to native and non-native Englishspeakers from all over the word at LandourLanguage School Mussoorie, India.I also have taught Hindi and Urdu tograduate and undergraduate students at TheUniversity of North Carolina, Chapel Hill NC, forone year in 2016-17.At Landour Language School, I worked asUrdu language coordinator for more than four yearsand as an integral member of the core teaching teamfor about eight years. The interdisciplinary andintense teaching experience at Landour LanguageSchool combined with my passion to teachlanguages and cultures have made me a betterlanguage teacher, who strives to be better all thetime.As an in-process project I am working on anUrdu textbook and as a future project I am reallylooking forward to develop an online Hindi-Urdutextbook too. As a language educator I want to workon simplification of the Hindi-Urdu grammarteaching practices. My further interests lay in thetopics like – teaching Hindi and Urdu throughcultural, religious, or Bollywood related texts andteaching Indian cultural practices in Hindi and Urdu,influence of the new and reinvented or revivedvocabulary on contemporary Hindi and Urduspeaking community, Garhwali language and Hindi,and dying languages in India.I hope to find myself as better educator in thecoming future in the great academic atmosphere ofthe University of Virginia.ABDUL NASIR

5 MESALC NEWSLETTERNEW COURSES2018ARTR 3559/5559Global Masterpieces from the ClassicalIslamicate World: A Comparative ApproachInstructor: Nizar HermesThis course explores the literary masterworks of some of the most celebrated authors of theclassical Islamicate world (500-1500). It gives students the chance to intensely and comparatively engagenotable global texts from “the medieval Islamic republic of letters,” to quote M. J. al-Musawi’sgroundbreaking The Medieval Islamic Republic of Letters: Arabic Knowledge Construction (2015).Students will cultivate an appreciation for the development of the intellectual history of the “medieval”Middle East (including North Africa and al-Andalus) alongside their engagement with such masterpiecesas Aesopica, Ars Amatoria, Confessiones, The Panchatantra, Tales of Genji, Tahkemoni, The Sundiata,The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales, Lazarillo de Tormes, Othello, Don Quixote, and Robison Crusoe.Drawing on both classical Arabic-Islamic and modern Western theories, we will further form comparativeinsights into the poetics and politics of the humanist topics encountered across our literary journeys intothe rich corpus of Arabic-Islamic adab (belles-lettres).MESA 1559Gateway to the Middle East & South AsiaInstructors: Tessa Farmer, Mehr FarooqiThe earliest human civilizations developed in the Middle East (also known as the Near East andWestern Asia) and South Asia. The cultures of these regions are deep and multilayered. Around 12000BCE the Natufian culture that emerged in Palestine and southern Syria domesticated the dog and beganprocesses that led to incipient cultivation and herding. Beginning from the Indus Valley some 5000 yearsago, civilization in South Asia presented a unique linguistic and cultural diversity, much of which wasowed to owed to settlers who poured in from the rugged regions of Central Asia and beyond.This course is an overview of the cultural dynamics as evident in the literature, arts, and culturalpractices from 4000BCE to the present. Needless to say, in the course of one semester we will offer abroad sweep of the past with an endeavor to understand the complexity of Middle Eastern and SouthAsian civilizations. Drawing on a selection from literary works as well as writings on history, artisticproduction, and the history of ideas, the course will guide the students through the landmarks in thedevelopment of cultural patterns, literature and the arts within a historical-cultural backdrop.The course will follow a chronological pattern. It will, however, focus more on the pre-modernand modern trends.As an introductory level course, it presupposes no pre-knowledge of the subject. Allundergraduates are welcome!

6 MESALC NEWSLETTERNEW PUBLICATIONSThe Beloved in Middle Eastern Literatures: The Culture ofLove and Languishing Alireza Korangy, Hanadi Al-Samman, Michael Beard I.B. Tauris, 2017In the long literary history of the Middle East, the notion of 'the beloved' hasbeen a central trope in both the poetry and prose of the region. This book explores theconcept of the beloved in a cross-cultural and interdisciplinary manner, revealinghow shared ideas on the subject supersede geographical and temporal boundaries,and ideas of nationhood. The book considers the beloved in its classical, modern andpostmodern manifestations, taking into account the different sexual orientations andforms of desire expressed. From the pre-Islamic 'Udhri (romantic unrequited love), tothe erotic same-sex love in thirteenth century poetry and prose, the divine Sufireflections on the topic, and post-revolutionary love encounters in Iran, Egypt andSaudi Arabia, The Beloved in Middle Eastern Literatures connects the affective andcultural with the political and the obscene. In focusing on the diverse manifestationsof love and tropes of the lover/beloved binary, this book is unique in foregroundingwhat is often regarded as a 'taboo subject' in the region.The multi-faceted outlook reveals the variety of philological, philosophical,poetic and literary forms that treat this significant motif.Min Fursān al-cArabiyya f̄i al-Qarn al-Tāsic cAshar:Studies in Nineteenth Century Arabic Mohammed Sawaie 2017The nineteenth century brought the Arab countries into closecontact with the West, mainly Britain and France, through colonization aswell as through the establishment of educational institution modelled onWestern establishments, especially in Egypt. This generated interest inlanguage issues and calls for reform of Arabic to express then newlyintroduced Western sciences and material culture. Arab scholars of theperiod expressed different views regarding these matters.The book comprises five essays on three leading nineteenthcentury scholars of Arabic. Three essays discuss linguistic efforts byAhmad Fāris al-Shidyāq, author, critic, translator, editor and founder ofthe famous newspaper Al-Jawā’ib in Istanbul in 1861-1874; one essaytreats the linguistic views of Jurjī Zaidān, author of several books onlanguage issues, essayist, and founder in 1892 of the famous al-Hilāljournal, which continues to publish today. The fifth essay discusses thelinguistic views of Abdulla Al-Nadīm, author, essayist, orator, andjournalist. Such debate on linguistic matters encountered in thenineteenth century continues today.

7 MESALC NEWSLETTERNE WP UB LI C AT I ON Sco n ti n u ed fr o m p a ge6Captive,Forugh Farrokhzad’s PoetryTranslated By: Farzaneh MilaniForugh Farrokhzad (1934-1967) was aconsummate reader of Iranian and Westernpoetry, a prolific poet, an award winningcinematographer, an artist in realms as variousas painting and sewing, acting and directing.The author of five poetry collections, a travelnarrative, six short stories, and hundreds ofletters,Farrokhzadwasthemostautobiographical of her contemporaries orperhaps all of Iranian literature. Her body ofwork reflects a complex mixture of traditionand modernity, resistance and acquiescence,protest and accommodation.Captive, translated by Farzaneh Milani,is the original edition of Asir, Farrokhzad’s firstpoetry collection. Few of these poems havebeen available in translation. Captive alsoincludes the first uncensored edition in theoriginal Persian without any of the subsequentomissions and alterations. Although the workof a youthful poet, Captive is intensely relevantto our time and to a better understanding ofIran and the role of women in that country.EDU C AT I ON AS ANT I D OT Eco n ti n u ed fr o m p a ge 2Ultimately, Jefferson never lost faiththat the “ball of liberty” will roll around theglobe. In an 1823 letter to revolutionarycompadre John Adams, Jefferson reflected that,“A first attempt to recover the right of selfgovernment may fail, so may a second, a third,etc. But as a younger and more instructed racecomes on, the sentiment becomes more andmore intuitive, and a fourth, a fifth, or somesubsequent one of the ever renewed attemptswill ultimately succeed.” Jefferson darklyanticipated “rivers of blood” and even “years ofdesolation” along the way, yet the object ofself-government was deemed worth the cost.Jefferson’s last public letter, composedto Robert Weightman ten days before his deathon July 4th, 1826, restated his global vision forthe Declaration of Independence:“May it be to the world, what I believeit will be — to some parts sooner, to otherslater, but finally to all — the Signal of arousingmen to burst the chains, under which monkishignorance and superstition had persuaded themto bind themselves and to assume the blessingsand security of self-government.”Yet what again today for our region offocus?Would Jefferson concur with theskeptics, the ones who did not see the ArabSpring coming, the same ones who nowconclude that the region was not ready, that therecent revolutionary struggles for freedom wereno more than a dream, a “false dawn?”Jefferson and John Adams both died onJuly 4th, 1826, 50 years to the day of the signingof the Declaration. Jefferson died first, yetAdams did not know that just before he utteredwhat are believed to be his last words,“Jefferson still survives.”Therein, some of us can hear aJeffersonian echo.“Tunisia still survives.”SCOTT HARROPWm. S co t t Ha r ro p i s cu r ren tly a Je ff er so nFel lo w a t th e Ro b e rt H. S mi t In t ern a tio n a lCen te r fo r Je ffe r so n S tu d ie s, a t Mo n ti cel lo . Heta u g h t va r io u s UV A co u r se s o n rec en trevo lu t io n s in th e Is la m i c wo r ld sin c e Ja n u a ry2 0 1 2 . Vi ew s exp re s sed h ere in a re h i s o wn .

8 MESALC NEWSLETTERSajedeh HosseiniSERVING AS A TA AT MR. JEFFERSON’SSCHOOL BRIGHTENED MY DAYSSaj ed e h (r i g ht ) wi t h h er cla s s.I was playing alone in the backyard andas soon as my mother heard me saying, “nazi,nazi [cutie, cutie], she ran towards me. By thetime my mother reached me, the cobra snakethat I was trying to pet, fled away. According toher, my staying alive is a miracle. Meeting acobra snake was the first major adventure of mylife. I grew up in Bangalore, India; the naturalhabitant of numerous wild animals, and I tried topet as many as I could. Both of my parents werestudents at the Bangalore University. Since then,I have been in love with animals. Growing up inthe Indian subcontinent, I displayed loads ofrespect for the Indian culture. I also continuedliving my imaginary Bollywood life when myfamily and I returned to Iran for my schooling.This was the reason why I majored in SouthAsian Studies as an undergraduate student at theUniversity of Tehran and later completed myMaster’s degree in South Asian Studies at theUniversity of Delhi.After serving in Tehran Milad Tower forfew years, I started my second Master’s in theMiddle Eastern and South Asian Languages andCultures (MESLAC) at the University ofVirginia, where I had the opportunityto teach Persian to undergraduate students. Ienjoyed every minute of teaching Persian. Thisteaching opportunity not only highlighted mygraduate school experience but it also helped me todetermine my professional aspiration. During aSufi Literature class with Professor Shankar Nair, Istarted my research about the role of animals in theMasnavī of Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī.Subsequently, my fascination towards animals andnon-humans in literature grew steadily.I am excited to report that I will start mydoctoral studies at the University of Arizona in thefall of 2018, where I will work on animals andnon-humans presented in the Sufi context. I havealso been fortunate to receive the RoshanFellowship for Iranian studies for the 2018-2019academic year that will help fund my studies. Iowe all of this to MESLAC because it provided mewith a platform to improve my knowledge aboutboth Iran and India during my academic journey.Studying at UVA had an immense influence in mypersonal life as well. I learned many life lessonsthat I will apply later on in my life.SAJEDEH HOSSEINI

9 MESALC NEWSLETTERMehr FarooqiA NIGHT OF GHAZALS AND SUFI KALAMP o o j a Go s wa mi P a va n ( ce nte r )Mehr Farooqi shared the stage as aninterpreter cum cultural commentator for theaudience that did not understand Urdu. Ghazals arepoems made up of two-line verses bound within ameter with an end rhyme and refrain. Thiscomplex arrangement of words makes the poemsvery musical. The theme of the ghazal is mostlylove, for a Divine Beloved or an earthly one.Ghazals tend to be metaphorical and abstract sothat a lot of thought can be packed into two lines.A distinctive feature of the program wasPooja’s rendition of the great nineteenth centuryUrdu poet Ghalib. She presented a ghazal that hasnever been sung before as it belongs to the corpusof Ghalib’s unpublished poems.Mohabbat ne zulmat se karha hai nurNa hoti mohabbat na hota zahuris qadar zabt kahan hai kabhi a bhi na sakunSitam itna to na kijeye keh utha bhi na sakun(Love has drawn light from darkness;But for love, there would be no manifestation)How can I restrain myself asks the poet?How much pain can I endure? If my house is onfire so be it. It is not the fire of love that cannot beextinguished. If you, my beloved, don’t come tome I can die. Death is not as elusive as you. If yousmile for me all past complaints are wiped away.But thoughts of you can never be erased.At the workshop with students and gueststhe following day, Pavan explained how she honedher singing. She spoke at length on how shemeditated on the verses she wanted to sing so thatshe could render the words with a deeperunderstanding of the meaning. For the studentsstudying classical Urdu poetry in the OngoingMahfil course, it was an unforgettable experience.Pooja Goswami Pavan’s mellifluous,hypnotic voice rendered verses from classicalUrdu ghazal poets and Sufi masters, to packedaudiences at the historic Old Cabell Hall onOctober 15, 2017. This was the first ever concertof ghazal poetry at the University of Virginia.Organized by Mehr Farooqi from MESALC inassociation with the Society for the Promotionof Indian Classical Music for Youth(SPICMACAY). The event drew students fromacross the university as well as musicaficionados from Richmond, Washington DC,Roanoke and other places.Pooja Goswami Pavan holds a PhD inIndian Classical Music from Delhi University.She was trained in semi-classical genres such asghazal, sufi kalam, thumri and dadra by theeminent vocalist Vidushi Shanti Hiranand.Pavan was accompanied by Pankaj Mishra onthe sarangi and Devapriya Nayak on the tabla.MEHR FAROOQI

10 M E S A L C N E W S L E T T E RJanaezjah RyderFROM PUNE TO UVAJ ana ezj a h R yd erI have always been interested in worldcultures. When I was younger, I read a lot ofnonfiction books about how people lived theirlives all around the world. However, I wasalways intrigued by the italicized words thatkept popping up throughout the books I wasreading and was frustrated that I didn’t knowthese foreign words. This led me down the pathof foreign languages, where I began to study theusual European languages offered in school andthen later tried to teach myself Hindi. Butwithout the proper resources, I knew I wouldnever really be able to learn the language.Fortunately, when I was a junior in highschool, I was granted the National SecurityLanguage Initiative Scholarship for Youth,which allowed me to spend a summer in Pune,Maharashtra, India. The program’s goal is toallow students interested in critical languagesthe opportunity to learn them in a native setting.This was the first time I had ever left the countryand the fact that I was going to be studyingHindi in a formal setting was almost as excitingas getting to be in India.I was assigned a host family and spentall day in an international school learning Hindi,cooking Indian food, acting out historicalscenes, Bollywood dancing and singingtraditional songs; while also receiving Hinditutoring from local students and teachingyounger children English. On the weekends, wewould go on excursions around the city. One ofthe most notable trips we took were to thedifferent places of worship, which were a Sikhgurudwara, a Christian church, a Hindu templeand a Jewish synagogue. This was especiallyinteresting because I had read so much aboutIndia and its diversity but had never gotten toexperience it up close. While in Pune, everyday was a new experience in which I learnedmore about the culture in India andMaharashtra. Being able to combine my interestin the Hindi language while experiencing theculture truly helped solidify my choice to studythis region formally.When I began applying to colleges, Iknew I needed to find a school that offeredHindi, and when I came to UVa, I knew Iwanted to learn more than just the language.Often I’m asked if I have had any experience orconnection with South Asia before choosing mymajor. Other than the National SecurityLanguage Initiative Scholarship for Youth andthe fact that I am from a black military family, Irespond that I had little to no interaction withSouth Asian culture. However, the supportivestaff really helped guide me on my path.Although I had come to UVa knowingthat South Asian Studies was the right major forme, one of the classes that made me feelconfident in my choice was Modern Hindi andUrdu Literature. This class essentially helpedcombine culture, history and literary traditionsthat I was beginning to become familiar with.However, for me, this class tested my culturalknowledge because I was able to use what Iknew from my experience in India coupled withthe knowledge from my previous classes toconnect with the texts we were reading. I havebeen so fortunate to have such a comprehensiveeducation and am grateful that I have been ableto study with passionate professors anddedicated students.JANAEZJAH RYDER

11 M E S A L C N E W S L E T T E RHanadi Al-SammanTHE AESTHETICS OF TRAUMAThis spring, MESALC associate professorand college fellow, Hanadi Al-Samman taughttwo sessions of a new College Engagement courseentitled, “EGMT 1510: The Aesthetics ofTrauma.” The course sought to teach studentstrauma theory and the ways in which aspects oftraumatic recall, postmemory, intergenerationaland transnational trauma can be expressedcreatively and affectively in works of art. Thecourse took the ongoing Syrian revolution andsubsequent civil war as a case study and as aportal to connect to other local and global tragicevents such as: the Charlottesville August 2017Hate rallies, the Holocaust, the PalestinianCatastrophe (Nakba), the African-AmericanMiddle Passage (Maafa), school shootings in theUS, and the MeToo Movement.Enrollment from both sections totaledmore than 70 students, many of whom were firstyears who felt like their class had been marked bythe tragic events of August 11th, 2017, when agroup of white supremacists bearing torchesinvaded UVA grounds chanting, “you will notreplace us,” and “Jews will not replace us.” Theconflict escalated the following day when acounter-protester at an alt-right rally in downtownCharlottesville, Heather Heyer, was killed when awhite supremacist slammed his car into the crowd.The incident took place just two weeksbefore the start of the fall semester, and manyincoming students felt that their class inherited theweight of this traumatic event. Even though mosthad not moved in yet, their ties to the communityleft students feeling the impact of this senselessviolence. “We all carry the postmemory of this eventbecause many of us only witnessed this tragedy onour television screens,” said Emily Elmore, one ofHanadi’s students. “We are all affected by whathappened in August because our school has beenforever marked by this event. Together, as acommunity, we must rise up against the hate in orderto cope with what happened.”As part of their final project for the class, thestudents had to create a visual display in which theyinterpret a traumatic experience in a way that elicitaffective resonance in the audience. Submissionsranged from a suitcase filled with items that aHolocaust survivor or a Syrian refugee might havecarried to a diorama of empty desks whichrepresented the lives lost during school shootings.Collectively the projects highlight the value ofempathic art that seeks to engage the audience in aninteractive, redemptive engagement, rather than theold-fashioned commemorative art function.I was blown away by the creativity of mystudent’s collective projects, by the various ways inwhich they used individual traumas to connect tocollective ones locally and globally. From schoolshootings, to the Charlottesville hate rally, toHungarian wars, Holocaust

then destroyed College at Geneva. The idea fired Jefferson's imagination, thirty years before the opening of UVA.) Despite the brutal turns of the French revolution, Jefferson still believed that America's example could be emulated elsewhere. Impressed by Tench Coxe's accounts of the Dutch (Batavian) revolution, Jefferson on