Transcription

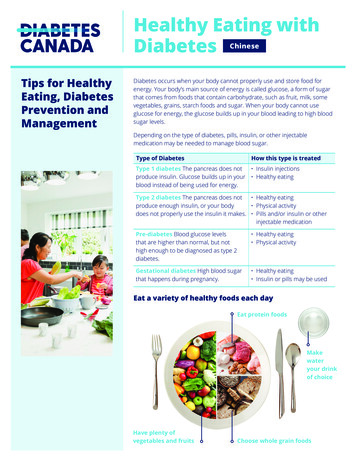

Volume 38 Number 3September/October 2019Practical Approaches to Diabetes and Related DiseasesClinical PerspectiveEATING PATTERNS: MYTHS AND FACTS2 LOW-CARBAmy Campbell, MS, RDN, LDN, CDEAre your patients asking about low-carb eating patterns? There issome merit to cutting carbs, especially because going lower-carbcan help improve glycemic control and perhaps make it easier toget and keep A1C and blood glucose levels within target range.Transition of CarePEDIATRIC TO ADULT DIABETES CARE:5 FROMSTRATEGIES FOR SUCCESSBrittany Bruggeman, MD, FAAP and Anastasia Albanese-O’Neill,PhD, APRN, CDETransition from pediatric to adult diabetes care should bestructured and purposeful. Utilization of available resources canreduce risks that the emerging adult will experience such as gapsin care and increase the probability of a positive and successfultransition.TO COLLEGE WITH DIABETES8 OFFKerry Milaszewski, BS, RN, CDE and Joyce Keady, MSN, CPNPTransition to successfully managing diabetes in college can befull of challenges, and being well prepared is essential. Supportand education provided by the diabetes care team plays a vitalrole in ensuring a healthy and successful transition.Columns11 COMMENTARYThe Link Between Obstructive Sleep Apneaand Type 2 Diabetes MellitusThis commentary by Dr. Ali Ershadi, Dr. Ian Weir and Dr. Nancy Rennertprovides awareness regarding the high incidence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)in those with type 2 diabetes as well as an understanding of the diagnosis andtreatment of OSA in these individuals.14 JOURNAL WATCHThis column highlights clinical trial data and landmark trials. Information forobtaining trial data and the references to the published articles are provided tofacilitate discussion with your patients and colleagues. The trial is identified bythe acronym and the ClinicalTrials.gov registry number (National Clinical Trials[NCT] Identifier). Outcome results are summarized.CORNER16 EDUCATOR’SDiabetes and Worksite WellnessAn individual with or at risk for developing diabetes likely spends at leastone-third of their day on the job. In many cases, the worksite may present specialchallenges. Dealing with worksite issues, providing resources and forging newhealth-care partnerships are essential components to promote a healthy andproductive workforce.Professional Supplement to

NEW!33G 110% thinner than 32Geas er.The only pen needlea built-in remover.It’s no ordinary pen needle.Discover the pen needle with a built-in removalchamber, designed to make pen needle removaleasier, safer and more convenient2 Proven to increase patient compliance by 61%2,3Patient preferred versus standard pen needles2,4Universal fit with all major brand injection pens5Covered under most third party insurance plans6NEW Unifine Pentips Plus 33G is our thinnest needle ever!Recommended for use by pediatric and highly compliant patients.1. Comparison of 33G to 32G max outer needle diameter in accordance with ISO 9626:2016 standards. 2. HRW (2014) Impact of Unifine Pentips Plus on pen needle changing behaviour amongst people withdiabetes medicating with injectable formats. 3. Compliance is defined as the changing of pen needle after every injection. 4. Unifine Pentips Plus was preferred by 61% of patients to their standard pen needle.4. Complete compatibility information available on owenmumford.com 6. Independent and chain pharmacy co-pay adjudication (April 2016). Actual coverage and co-pay may vary from setting to setting, andinsurer to insurer. Data on file. 7. Available for healthcare professionals while supplies last. Please allow up to 10 weeks for samples to ship. PD2019ADVA/OMI/1018/1/USTO REQUEST FREE SAMPLES7visit unifinepentipsplus.com or call 1-800-421-6936

P R A C T I C A L A P P R O A C H E S T O D I A B E T E S A N D R E L AT E D D I S E A S E SEDITORIALEditorLaura Hieronymus, DNP, MSEd, RN,MLDE, BC-ADM, CDE, FAADEAssociate Director, Education andQuality ServicesUK HealthCare Barnstable BrownDiabetes CenterUniversity of KentuckyLexington, KYEditor, Educator’s CornerMeghan Jardine, MS, MBA, RDN,LD, CDEAssociate Director ofDiabetes Education,Physicians Committee forResponsible MedicineWashington, DCEditorLydia GoernerSenior Digital EditorDiane FennellAssociate EditorMatthew BernatAssociate EditorsSandra Drozdz Burke, PhD, APRN,FAADE, FAANAssociate Professor (retired),University of Illinois at ChicagoCollege of NursingChicago, ILRobert “Bob” Chilton, DOProfessor of Medicine, Division ofCardiologyThe University of Texas HealthScience Center at San AntonioSan Antonio, TXEditorial BoardJackie Boucher, MS, RDNPresident of Children’s HeartLink,Minneapolis, MNShana Cunningham, MSN, RN, MLDE,BC-ADM, CDEDiabetes Education ServicesCoordinator, University ofKentucky HealthCareBarnstable Brown Diabetes Center,Lexington, KYCOVER IMAGE: GEORGE DOLGIKH/SHUTTERSTOCKTammy DiMuzio, MS, RN, CDEClinical Program Manager,Diabetes Center,Cincinnati Children's Hospital,Cincinnati, OHSanjoy Dutta, PhDAssociate Vice PresidentResearch, and International Partnerships, JDRF,New York, NYSteven Edelman, MDFounder and Director, Taking Controlof Your Diabetes,San Diego, CAMarion J. Franz, MS, RDN, CDENutrition Concepts by Franz,Minneapolis, MNGeorge Grunberger, MD, FACP, FACEGrunberger Diabetes Institute,Bloomfield Hills, MIAlissa Heizler-Mendoza, MA, RDN,CDESenior Director of Advocacy, InsuletCorporation,Newtown, CTRichard Hellman, MD, FACP, FACELawrence and Memorial Hospital,Waterford, CTRobert Ratner, MDMedStar Washington HospitalCenter,Washington, DCNancy J. Rennert, MD, FACE, FACPNorwalk Community Health Center,Norwalk, CTJulio Rosenstock, MDDiabetes & Endocrine Center,Dallas, TXJane Jeffrie Seley, DNP, MPH, MSN,GNP, BC-ADM, CDE, FAADEDivision of Endocrinology,Diabetes & Metabolism,Weill Cornell Medicine,New York, NYEvan Sisson, PharmD, MSHA, BCACP,CDE, FAADEAssociate Professor, Department ofPharmacotherapy and OutcomesScience,Virginia Commonwealth University,Richmond, VASusan Weiner, MS, RDN, CDE, FAADEOwner, Susan Weiner Nutrition, PLLCLong Island, NYJoel Zonszein, MDBurke Rehabilitation Hospital andMontefiore Medical Center,Bronx, NYPUBLISHING STAFFChairman & Chief Executive OfficerJeffrey C. WolkChief Operating OfficerPeter MaddenEDITOR’S NOTE“People don’t care how much you know until theyknow how much you care.”-Theodore RooseveltData show that health care professionals whohave the best success with patient acceptance oftreatment plans are those who create a personalrapport and inspire patients’ trust in themselves and their practice. Onestudy reported that autonomy with health decision-making rankedabove a physician’s expertise with respect to patient perceptions of agood physician.I believe that as diabetes health care professionals, we all strive to learnanything and everything we can to ensure our patients have optimal,evidence-based, expert diabetes care and education. We have advancedknowledge to help our patients learn how to adapt to each day in their lifewith diabetes. After diagnosis, a chronic illness such as diabetes affectsevery single thing our patients do such as eating, sleeping, going to school,and working. And we share our knowledge with other health care professionals by writing about it. Yes, it is truly important to stay informed.But let’s not forget about the importance of our customer service skills.Our patients are, in essence, our customers. Effective customer serviceincludes being accessible, courteous, and honest and listening to whatour patients have to say. Good customer services—by all providers andstaff—can help to bring our patients back, which fosters patient-centeredcare and supports patient engagement.So let’s be sure to show our patients how much we care; then, perhaps,they will better appreciate how much we know.Senior Vice President,Sales & MarketingRobin MorseVice President,Business OperationsCourtney WhitakerAccountingAmanda Joyce, Tina McDermott,Wayne TuggleClient Services SupervisorCheyenne CorlissSenior Client Services AssociateTou Zong HerEditorLaura HieronymusDNP, MSEd, RN, MLDE, BC-ADM, CDE, FAADEPractical Diabetology is a supplement to Diabetes Self-Managementand is published quarterly by Madavor Media, LLC25 Braintree Hill Office Park, Suite 404, Braintree, MA 02184Copyright 2019 Madavor Media, LLC.Client ServicesAubrie Britto, Darren Cormier,Andrea PalliArt DirectorCarolyn V. MarsdenGraphic DesignerJaron CoteADVERTISING SALESStuart Crystal, scrystal@madavor.comStatements and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarilythose of the advertisers or publisher.Practical Diabetology is a member of Business Publications Audit of Circulations, Inc.Copy EditorToni FitzgeraldIn memory of Susan Fitzgerald,COO, 1966-2018To submit a manuscript to this journal, email PDeditor@madavor.com.If you have questions or comments on this issue, email PDeditor@madavor.com.Practical Diabetology Vol. 38, No. 3 Fall 20191

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVELOW-CARB EATING PATTERNS:MYTHS AND FACTSAsk any of your patients who have diabetes whatthey find to be the most challenging aspect of havingdiabetes. Most of them will likely say that figuringout what to eat, following a meal plan and balancingout carbs with diabetes medicine. This history ofthe “diabetic diet” is long and convoluted. Beforeinsulin was discovered, a very low-carbohydrate,starvation approach was really the only option toprolong life. After insulin was discovered in theearly part of the 20th century, Elliott P. Joslin andother health care professionals recommended aneating plan of 40% of calories from carbohydrate,40% of calories from fat, and 20% of calories fromprotein. The composition shifted yet again towardthe latter part of the 20th century to one of approximately 50 to 55% of calories from carbohydrate,30 to 35% of calories from fat, and 15 to 20% ofcalories from protein as a result of concern over theincreased risk of cardiovascular disease in peoplewith diabetes. The culprit was believed to be anexcess of calories from fat.With the growing popularity of lower and lowcarbohydrate diets for weight reduction, many healthcare providers and people with diabetes began toquestion the sensibility of recommending and fol-2lowing, respectively, eating plans with 50% or moreof calories from carbohydrate. Not only did a highercarbohydrate eating plan require more diabetesmedication (including insulin), but also evidencesuggested that the amount and type of carbohydrate consumed could adversely affect heart health.The rise of a host of lower-carb eating plans gainedmomentum in both the medical community and thediabetes community: Dr. Atkins, The Zone Diet andThe South Beach Diet grew in popularity. Today, thetop contenders for low-carbohydrate eating includethe Paleo diet and the Ketogenic (Keto) diet.Carbohydrates (carbs for short) seem to becomemore maligned every day. And not just for peoplewho have diabetes. Feeling tired and draggy? Feeling blue? Have a stomachache? Gaining weight?Blame carbs. Websites such as lowcarbyum.com andlowcarbmaven.com and books like “Wheat Belly”and “Grain Brain” are dedicated to slashing carbsand make it appear simple to get started. These dietscan indeed be beneficial in helping people drop bodyweight and blood glucose levels at the same time.Researchers have been taking a closer look at theseeating plans as well, with more and more studies insupport of the “low-carb” movement. And whatPractical Diabetology Vol. 38, No. 3 Fall 2019YULIA 1971/SHUTTERSTOCKAmy Campbell, MS,RDN, LDN, CDEDiabetes Program Manager,Good Measures, LLCBoston, MA

about the American Diabetes Association (ADA)?Often wrongly blamed for promoting high-carb eating, the ADA nutrition recommendations, recentlyupdated in May of 20191, clearly state that there isno ideal percentage of calories from carbohydrate,protein and fat for all people with diabetes. The 2019ADA Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes2 state:“Macronutrient distribution should be based on anindividualized assessment of current eating patterns,preferences, and metabolic goals.” A variety of eatingpatterns—including lower-carb—are acceptable formanaging diabetes. Yet despite the growing acceptance of lower-carb eating plans, misconceptionsabout them still abound. Let’s take a look at somecommon low-carb questions that your patients mayask you, along with suggested answers.Evaluating low-carb claimsClaim: All carbs are bad. Period.False. Thinking that every carb food is “bad” is avery misinformed and dangerous assumption. Plus,falling into the “good food/bad food” mentalitycan make it hard to eat healthfully. The fact is,almost all foods have their high and low points.Even something as seemingly unhealthy as, say,McDonald’s Double Bacon Smokehouse Burger,with 1,130 calories, 64 grams of carb and 1,920milligrams of sodium, has some merits (protein,vitamin B12, iron).Are some carb foods not so healthy? Sure. Cookies, candy, cake and soda are a few examples. Onthe flip side, there are plenty of carb foods that arehighly nutritious, such as sweet potatoes, quinoa,black beans and raspberries. Refined carbs (e.g.,cookies, cake, soda, white bread, white pasta) arethe types of carbs to limit, whereas unrefined carbfoods, such as vegetables, fruit, whole grains andlegumes, are good bets. The goal is to help patientsfocus on including “quality” carb foods in theireating plans – these are foods that are rich in fiber,vitamins and minerals, and low in added sugars,fats and sodium.1Claim: Lose weight on a low-carb diet.True. If one is carrying extra weight and a healthgoal is to lose a few (or a lot of) pounds a low carb dietmay help. For overweight individuals, data show thatlosing between 5 and 10% of body weight can leadto a number of benefits, including a lower hemoglobin A1c (A1C), decreased insulin resistance, lowerblood pressure, lower blood lipids and improvedsleep apnea, not to mention improved quality of life.One of the misconceptions about lower-carbeating plans is that they are better for weight lossthan a higher-carb plan. In the short term, maybe.Yet research shows that over time, this may not betrue. The POUNDS LOST study3 for example,tested four diets that varied in carb, protein and fat.There were 811 participants in this study, who wereassigned one of four diets to follow. After six monthsand two years, respectively, weight loss was similar.Furthermore, all four diets showed an improvementin cardiovascular risk factors, such as cholesterol,triglycerides and blood pressure. A more recentstudy, the DIETFITS trial4, randomized 609 adultsto follow a low-carb or a low-fat diet. After one year,there was no significant difference in the amount ofweight loss between the two groups.What many healthcare professionals and patientsdon’t realize is that going low-carb isn’t the onlyway to lose weight: evidence points to other eatingpatterns, such as Mediterranean-style, vegetarian/vegan, low-fat and DASH (Dietary Approaches toStop Hypertension) eating patterns as helping topromote weight loss, if warranted, and then supporting weight maintenance once the desired weightgoal is achieved.1According to Melinda Maryniuk, a nationallyrecognized registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN)and certified diabetes educator, “The usual limitingfactor for achieving success with a low-carb diet isthat people tire of the limited food choices. If yourpatients feel like they can stay with a low-carb eatingplan over time (and have family support), try it andsee how it works.”Claim: Carb foods are off limits on a low-carb diet.False. A low-carb diet doesn’t necessarily mean ano-carb diet, nor would it be simple to cut out allcarbs from an eating plan, although it is definitelypossible. There are a number of versions of low-carbdiets out there. Some of the more popular include: Zero-Carb Diet: No fruits, vegetables orstarches — just meat, poultry, eggs and cheese.And water. Ketogenic (Keto) Diet: Less than 50 grams ofcarb per day; heavy on fats and protein foods,with limited amounts of fruit. Atkins Diet: Starts with a very-low-carb plan,and then gradually adds back carbs. South Beach Diet: Like other plans, this is alsohigher in lean protein and fat, with differentphases whereby healthy carbs are added back.Unfortunately, there is no universally accepteddefinition of a low-carb diet, which can cause con-Practical Diabetology Vol. 38, No. 3 Fall 2019Visit PracticalDiabetology.comfor more diabetes clinical news3

fusion. What may be low-carb to you can seemlike way too much carb for someone else. Healthcare providers may recommend a low-carb diet tohelp manage diabetes or weight loss goals withoutspecifying what the diet should involve. Feinmanand colleagues5 attempted to set some parametersaround the meaning of “low carb” by proposing thefollowing definitions: Very low carb/Ketogenic: 20–50 grams of carbper day (less than 10% of total calories) Low carb: Less than 130 grams of carb per day(less than 26% of total calories) Moderate carb: More than 130 grams of carbper day (26% to 45% of total calories) High carb: More than 225 grams of carb perday (more than 45% of total calories)Interestingly, research shows that, on average,people with diabetes consume approximately 45%of their calories from carbohydrate, 36 to 40% ofcalories from fat, and 16 to 18% of calories from protein which is about the same as the general public.1Claim: The American Diabetes Association supportslower-carb eating plans for people with diabetes.True. The ADA actually is supportive of manydifferent types of eating patterns, including Mediterranean, DASH (Dietary Approaches to StopHypertension), lower fat, vegetarian, use of mealreplacements and yes, lower carb. In fact, ADA’sStandards of Medical Care in Diabetes, releasedevery year in January, acknowledge (and have forseveral years now) that low-carb eating plans (lessthan 50 grams/day) are linked with improved outcomes for three to four months. More recent researchindicates that these outcomes may extend for at leasta year. It is important to note that no single mealplanning approach has been proven to be “consistently superior,” with more research needed todetermine the optimal type of eating pattern forpeople with diabetes.Is a lower-carb eating plan a good choice?REFERENCESSee page R14Help your patients avoid getting caught up in thelow-carb hype that is rampant across the internetand the office water cooler. There is certainly somemerit to cutting carbs, especially because goinglower-carb can help improve glycemic controland make it easier to get and keep A1C and bloodglucose levels within target range. In some cases,decreases in the amount of diabetes medication mayoccur as well.6 In fact, ADA’s recent nutrition recommendations clearly state that, “for select adultswith type 2 diabetes not meeting glycemic targetsor where reducing antihyperglycemic medicationsis a priority, reducing overall carbohydrate intakewith low- or very-low carbohydrate eating plansis a viable approach.1In contrast, eating patterns that are moderatecarb, such as Mediterranean style and a lowerglycemic approach (think whole grains, a lot ofvegetables, lean protein) can also help people withdiabetes achieve their glycemic goals.If your patients are feeling confused about goinglow carb, Maryniuk recommends your patients askthemselves the following:1. What foods might you have to give up (or, atleast, drastically cut back on)? Are you willingto do this? How will going lower carb impactyour spouse, partner or family?2. Is this a plan that you will stick with for the longterm? If you want to try a low-carb approach togive you a jump start, make sure you have a planto move to a healthy eating plan longer-term.3. Are there any risks of following a lower-carbplan? (Risks can include having kidney diseaseor osteoporosis.)4. Have you talked with your health care providerabout going lower carb? If you go lower carb, doyou know how to adjust your insulin or otherdiabetes medicine, if necessary?Going low carb isn’t for everyone; however,controlling carb intake is important with diabetes.Because carbohydrate requirements can vary fromperson to person, refer your patients to an RDN todiscuss carb goals. Until then, the following can behelpful to get your patient started: 45 to 60 grams of carb per meal. 15 to 30 grams of carb per snack. To lose weight, subtract 15 grams of carb fromeach meal. If very active or need to gain weight, add 15grams of carb to each meal.Expert referralAll patients with diabetes should be actively engagedin ongoing education, self-management of diabetes,and treatment planning with the diabetes care team.Collaboration with the RDN for medical nutritiontherapy (MNT) to determine a dietary plan fordiabetes is an essential part of care.1 MNT is associated with decreases in A1C of 1.0 to 1.9% in type 1diabetes and 0.3 to 2.0% in type 2 diabetes.7 Takeaction to refer patients to a RDN, ideally one whospecializes in diabetes and weight management, foran individualized dietary meal pattern and to getquestions answered. PDPractical Diabetology Vol. 38, No. 3 Fall 2019

TRANSITION OF CAREFROM PEDIATRIC TO ADULT DIABETES CARE:STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESSDespite ongoing improvement in diabetes care, whichincludes increased use of diabetes technology, themajority of young adults with type 1 diabetes (T1D)do not meet glycemic targets set forth in clinical guidelines.1 Each year, tens of thousands of young adultswith T1D transition from pediatric to adult care, andthis transition is accompanied by unique challenges.2During this vulnerable time, lack of parental involvement, financial struggles, irregular schedules, poordiet, peer pressure, drugs and alcohol, inconsistentclinic attendance and fear of hypoglycemia are allbarriers to optimal diabetes outcomes.3 These youngadults must assume responsibility for navigating thehealth-care system at a time when they are also navigating transitions to the workplace or to college andindependent living, and potentially being uprootedfrom their established diabetes support network.Gaps in diabetes care can lead to deteriorating diabetes outcomes, acute complications, development ofundetected chronic complications, and psychosocialstressors.2 Successful transition from pediatric to adultcare and to self-sufficient diabetes management is achallenging but critical objective.Emerging adulthood and young adulthoodContemporary voices in developmental psychologypropose that the post-adolescent period is dividedinto two stages: 1) emerging adulthood in the yearsimmediately after high school ( 18 to 24 years) and2) young adulthood during the time when traditionaladult roles are adopted ( 25 to 30 years).4 Thinkingabout patient care within this framework can helpthe clinician to match diabetes management recommendations appropriately to the post-adolescent’slife experiences and readiness to become fully independent in their own diabetes management.In emerging adulthood (18 to 24 years of age),individuals may be moving to new jobs, college,social interactions or living away from home forthe first time. Diabetes care may become secondary to these competing priorities. At the same time,emerging adults may not have assimilated all ofthe skills necessary to independently manage theirdiabetes. For these reasons, it may be impracticalto expect emerging adults to make major changesto their diabetes management or even to transitionto a new diabetes provider (Table 1).2In young adulthood (25-30 years of age), manyindividuals have an established identity and morestability, such as full-time work or an intimatepartnership. This phase is often accompanied bynewfound appreciation of the importance of selfcare behaviors and glycemic management to overallhealth. Since many enduring patterns of behavior areestablished during this period, it is an important window of opportunity for health-care interventions.2Diabetes care challenges in emerging and youngadulthoodOnly 17% of T1D emerging adults and 30% of youngadults meet current glycemic targets.1 Emerging andyoung adults are less likely than any other age groupto maintain a medical home and are more likely toutilize emergency departments for care.5 Competingpriorities in this life stage often interfere with consistent medical care and place young adults at highrisk for health care disengagement, including gapsin visits with the diabetes care team. Up to half ofpeople in this age group will develop chronic diabetescomplications, including retinopathy, neuropathyand hypertension.6 The relative risk of death is higherfor young adults with diabetes than for those without.7 Lapses in care due to missed appointmentsaccount for some of these adverse outcomes.8At the same time, young adults may haveincreased alcohol consumption, changes in/reducedphysical activity, less access to nutritional foods, anddecreased motivation for self-care behaviors such asself-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG), leadingto further risk for complications. Young adults withT1D have similar rates of substance use as the general population, including alcohol use (47.0%), bingedrinking (29.9%) and smoking (34.7%).9 They arealso at high risk for psychosocial challenges. Up toone-third of young adults with T1D have diabetesrelated distress, anxiety or depressive symptoms,which are associated with worse glycemic outcomesand chronic and acute diabetes complications.10-11Brittany Bruggeman,MD, FAAPFellowUniversity of Florida,Division of PediatricEndocrinologyGainesville, FloridaAnastasia AlbaneseO’Neill, PhD, APRN, CDEAssistant Clinical ProfessorDirector of DiabetesEducation and ClinicOperationsDivision of PediatricEndocrinologyDepartment of PediatricsUniversity of FloridaGainesville, FloridaTransition of careThe majority of emerging adults with T1D transfer to adult care between ages 18 to 22 years, andPractical Diabetology Vol. 38, No. 3 Fall 20195

as noted above, this is a high-risk time period in avulnerable population. If transition does not happen successfully, individuals are at higher risk forpoor glycemic and psychosocial outcomes as well ashospitalization.12-13 The goal of an effective transition is to provide developmentally appropriate,uninterrupted health-care services as an individualmoves from adolescence to adulthood.14 Clinicianswho care for emerging and young adults with T1Dneed to evaluate the mental health and substance usepatterns of their patients and ensure access to mentalhealth providers and appropriate education.2 Bothpediatric and adult providers should provide support and links to resources to combat these barriersto successful diabetes management.2Transition can be divided into three stages:preparation, formal transition and evaluation. Astructured transition program incorporating thesestages can promote increased clinic attendance andsatisfaction with care and decrease diabetes-relateddistress.15 If transition must occur during emergingadulthood, the process should be purposeful andstructured in a way that includes significant levelsof support and assistance.Stages of transitionPreparationThe preparation for transition can be thought of intwo realms: the individual’s transition to independently managing T1D and the physical transitionof care to an adult diabetes provider. Ideally, thetransition of responsibility for T1D management tothe emerging adult should be a gradual one, shepherded by the health-care team and the patient’sfamily and social support systems. There should bea steady and gradual transfer of responsibility fordiabetes management from parent to child across theadolescent years, beginning as early as age 11. Theseresponsibilities include not only day-to-day tasks,such as glucose monitoring and insulin delivery, butalso scheduling office visits, ensuring the availabilityof adequate supplies and navigating insurance andhealth-care systems. The health-care team shouldprovide intentional education to adolescents surrounding these topics, and the emerging adult’sdiabetes knowledge and skill competencies shouldbe objectively measured, not assumed.2The transition of care from a pediatric to an adulthealth-care provider can be intimidating and requiresTable 1Transition Challenges and Solutions (Adapted from Peters et al., 2011)Challenges in the Transition PeriodPotential SolutionsLife transitions, including changes in living situation, employmentand social relationshipsPeer support groupsGradual shift in responsibility for diabetes managementStability of diabetes team during periods of life transitionsIncreased public awareness of T1D demandsDecreased motivation for self-care behaviorsMotivational interviewingPeer support groupsPoor diet and erratic schedulesDevelopmentally appropriate dietary and exercise counselingSubstance use and risky behaviorsRoutinely include substance use questions in diabetes careTargeted education regarding diabetes and substance useRoutine monitoring of psychosocial adjustmentIncreased psychologic distressAppropriate mental health screeningReferral to mental health providers and resourcesHealth care disengagement and loss to follow upStructured transition program, including preparation, formaltransition and evaluationGaps in health insuranceIntentional education by health-care team about maintaininginsurance coverage and navigating the health-care systemFundamental differences in health care delivery between pediatricand adult providersEducation about adult health-care systemAssess readiness for transition and match transfer time withperceived readinessFacilitate referrals to adult medical careDirect communication between pediatric and adult health-careteamsRecognize continued supportive role of parents in emergingadulthood6Practical Diabetology Vol. 38, No. 3 Fall 2019

advanced preparation. Unfortunately, fewer than halfof adolescents discuss transition of care to an adultprovider with their health-care team.12 This lack ofdialogue results in

This commentary by Dr. Ali Ershadi, Dr. Ian Weir and Dr. Nancy Rennert provides awareness regarding the high incidence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in those with type 2 diabetes as well as an understanding of the diagnosis and treatment of OSA in these individuals. JOURNAL WATCH This column highlights clinical trial data and landmark trials.