Transcription

CommonNative Treesof VirginiaVI RGI NIATree Identification Guide2010 EditionVirginia Department of Forestr ywww.dof.virginia.gov

Educating Our Youth AboutVirginia’s ForestsEach summer, Holiday Lake Forestry Camp introduces teens to ourstate’s forest resources and their management. The camp is sponsoredby the Virginia Department of Forestry, in cooperation with other agencies,organizations and businesses. Sponsorships enable all campers to participateat a minimal personal cost.Forestry Camp is designed for students with an interest in natural resourceconservation who may want to explore forestry and other natural resourcecareers. Educators may also participate in camp, earning recertificationpoints and receiving Project Learning Tree training.Forestry Camp is a hands-on, field-oriented experience. It takes place atHoliday Lake 4-H Educational Center, located in the 20,000-acre AppomattoxBuckingham State Forest. Theworking forest provides a vastoutdoor classroom for interactivelearning, with instruction fromprofessional foresters, biologists,and other resource specialists.Subjects include forest ecology andmanagement; timber harvesting andreforestation; tree identification andmeasurement; wildlife managementand habitat improvement, andenvironmental protection.Additional activities include fieldtrips, demonstrations, exploratorysessions and competitions.Nominations for ForestryCamp are accepted each yearbeginning in January. For moreinformation, visit the VirginiaDepartment of Forestry’s Web site:www.dof.virginia.gov

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideForewordWelcome to the most up-to-date and accurate edition of the Common Native Treesof Virginia (a.k.a. the Tree ID book) ever published. Through the hard work of severaldedicated employees of the Virginia Department of Forestry and the importantcontributions of others outside the Agency, this book – first published in 1922 – hasbeen revised to make it more useful for students and others interested in correctlyidentifying the most common trees growing in the Commonwealth of Virginia.Because of their efforts, you now have the best tool for proper, basic identification.To enhance your experience with this book, we have included a key that will enableyou to quickly identify the tree species and reduce the amount of time spent searchingthe guide. You’ll also find a range map for each of the species. And we’ve includedinformation on Virginia’s State Forests, where you can walk or hike the trails to seemany of the species highlighted in the book.Throughout the development of this edition of the Tree ID book, our focus was alwayson you – the end user. We hope you will agree that the resulting Common NativeTrees of Virginia book more than meets your needs, and that it serves to furtherinspire your interest in and love of Virginia’s forests.Carl E. Garrison IIIState ForesterRed Mulberry1

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideAcknowledgementsWriting:Ellen Powell – Virginia Department of ForestryLayout and Design:Janet Muncy – Virginia Department of ForestrySpecies Illustrations:Juliette Watts – USDA Forest Service, Northeastern AreaRange Maps:Todd Edgerton – Virginia Department of ForestryKey to Common Native Trees of Virginia:Joe Rossetti – Virginia Department of ForestryEditing:Janet Muncy and John Campbell – Virginia Department of ForestryContent Review:Joe Lehnen, Dennis Gaston,Gerald Crowell, Dennis Anderson,Patti Nylander, James Clark,Barbara White, Joe Rossettiand Karen Snape – VirginiaDepartment of ForestrySugar MapleThe Department of Forestrythanks Dr. John Seiler and JohnPeterson of Virginia Tech’sCollege of Natural Resources,for permission to use some textfrom their dendrology Web site. 2009 Virginia Department of Forestry2

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification ��s Forest Resources.7The Future Depends On You.8How to Use This Book.9Identification of Trees.10Parts, Types and Positions of Leaves. 11Types of Leaf Margins.12Leaf Placement.12Landscaping With Firewise Tree Species .13Key to Common Native Trees of Virginia.14Eastern White Pine.22Shortleaf Pine.23Loblolly Pine.24Longleaf Pine.25Pitch Pine.26Virginia Pine.27Pond Pine.28Table Mountain Pine.29Red Spruce.30Eastern Hemlock.31Baldcypress.32Atlantic White-cedar.33Northern White-cedar.34Eastern Redcedar.35Black Willow.36Eastern Cottonwood.37Bigtooth Aspen.38Black Walnut.39Butternut.40Bitternut Hickory.41Shagbark Hickory.42Mockernut Hickory.43Pignut Hickory.443

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideContents, continuedRiver Birch.45Yellow Birch.46Sweet Birch.47Eastern Hophornbeam.48American Hornbeam.49American Beech.50American Chestnut.51Alleghany Chinkapin.52White Oak.53Post Oak.54Chestnut Oak.55Swamp Chestnut Oak.56Live Oak.57Laurel Oak.58Northern Red Oak.59Southern Red Oak.60Black Oak.61Scarlet Oak.62Blackjack Oak.63Pin Oak.64Water Oak.65Willow Oak.66American Elm.67Slippery Elm.68Winged Elm.69Hackberry.70Red Mulberry.71Cucumbertree.72Sweetbay.73Fraser eetgum.78Sycamore.794

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideContents, continuedDowny Serviceberry.80Black Cherry.81Eastern Redbud.82Honeylocust.83Black Locust.84American Holly.85Boxelder.86Sugar Maple.87Red Maple.88Silver Maple.89Striped Maple.90Yellow Buckeye.91American Basswood.92Flowering Dogwood.93Sourwood.94Blackgum.95Water Tupelo.96Common Persimmon.97White Ash.98Green Ash.99Non-Native Invasive Species.100Tree-of-Heaven.101Mimosa.102Royal Paulownia.103Norway Maple.104White Poplar.105Chinaberry.106Other Trees in Virginia.107Project Learning Tree (PLT).109Virginia Master Naturalist Program.109Glossary. 110Virginia’s State Forests. 114Things to Do on State Forests. 114Virginia’s State Nurseries. 118Bibliography . 1195

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideOther Resources. 119Index.120Virginia Department of Forestry Contacts.128State Forests.128Nurseries.128Regional Offices.128Black OakChestnut Oak6

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideVirginia’s Forest ResourcesForests cover nearly two thirds of Virginia, and they are truly our “common wealth.”Forests provide us with environmental, economic and cultural benefits that improveour quality of life. Forests filter our water, clean our air, moderate our climate, providewildlife habitat, protect and enhance the soil, and offer recreational opportunities.They are scenic places for observing nature and renewing the spirit. Forestsalso provide thousands of products we use daily, such as lumber and paper, andthousands of jobs for our citizens.A forest is much more than trees. It is an ecological system made up of all theorganisms that inhabit it – from trees to mosses, and from birds to bacteria. All areinterdependent, and the interactions among the living components of the forest andthe physical environment keep a forest productive and self-sustaining for many years.Virginia has been called an “ecological crossroads,” as both southern and northernecosystems are found here. From the Cumberland Plateau to the Eastern Shore, animpressive array of plant and animal species inhabit a tremendous diversity of naturalcommunities.Forests are constantly changing. Sometimes the changes are swift, as a result of fire,ice, wind or timber harvest. At other times, the changes stretch across many years.Nearly all of the natural forests in Virginia have been extensively modified by humanactivities over hundreds of years. Most of the Piedmont and Coastal Plain forestswere cleared for agricultural use in Colonial times. The mountains were cut over forcharcoal, lumber and salvage of diseased trees through the early 1900s. Many siteswere harvested or cleared several times for farms or pasture, then later abandoned,to be reforested over several generations. Nowadays, forests are much more likelyto be managed with an eye toward the future. The Virginia Department of Forestryencourages landowners to manage their forests in a responsible and sustainablemanner.The greatest threat to our forests is the conversion of forest lands to other uses.Rapid population growth places a demand on our shrinking forest land base. Virginialoses more than 27,000 acres of forest land each year, mainly through conversionto home sites, shopping centers, roads and other developments. When forests aremanaged responsibly, harvesting of trees improves forest health or makes way fora new, young forest. In contrast, when land is developed, it will probably never beforested again. Land-use changes cause fragmentation of large parcels of land, asthey are broken into smaller blocks for houses, roads and other non-forest uses.Fragmentation limits the options for forest management because the land units aresmaller. It threatens those wildlife species that need sizable habitat free of constantdisturbance and human competition. Forest land loss and fragmentation also threatenthe scenic beauty of Virginia’s natural landscape, which delights residents and attractsmillions of tourists each year. Conserving the state’s forest land base is a major focusof the Virginia Department of Forestry.7

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideThe Future Depends On YouWhether or not you own forest land, you use forest products, enjoy outdoor activities,depend on clean water and fresh air, and view wildlife. Here are some things you cando to help Virginia’s forests: Learn as much as you can about natural resource issues. Shop responsibly; use resources wisely, and recycle. Support organizations that work to conserve and sustain forests and relatedresources. Encourage land-use planning and conservation easements. Promote sustainable management to maintain Virginia’s working landscapes. Teach others about the value of our forests.For more information about Virginia’s forests, visit the Virginia Department ofForestry’s Web site: www.dof.virginia.govAmerican Chestnut8

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideHow to Use This BookThis book describes the most common native tree species found in Virginia’sforests. It is intended to be a beginning tool for tree identification, rather than acomprehensive listing or technical manual. Therefore, non-technical descriptionshave been used whenever possible. The basic key provides a quick identification tool,minimizing the time spent searching for an unknown tree. The species descriptionsare good for general reference, but individual trees may vary within a species. Forexample, tree height at maturity may vary a great deal because of the growing site,tree health, genetics, competition and other factors. Some more complete resourcesfor tree identification are listed in the bibliography, and numerous other books andcomputer resources are available to enhance your study. At the back of this book, youcan also find a list of State Forests and other places to study trees.In this text, the most accepted common name is the primary heading for eachspecies, with additional common names listed below it. The scientific name, which isconsistent worldwide and most useful for true identification, is listed in the format ofthe International Code of Botanical Nomenclature: genus, species and author citation.The species’ native range is indicated by the shaded section of the map; however, it ispossible to find almost any tree growing outside its native range. For those desiring tolearn more technical terms or clarify definitions, a glossary is included.Flowering Dogwood9

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideIdentification of TreesMany characteristics can be used to identify trees. These include overall size andshape of the tree; size, shape and arrangement of leaves; texture, color and shapeof twigs and buds; color and texture of bark; and characteristics of fruit and flowers.Knowing the tree’s natural range and typical growing sites is also helpful. Most peopleuse a combination of several characteristics to identify trees.When leaves are present, they are the most commonly used feature in identification.Leaves are either deciduous (shed annually) or evergreen (remaining on the tree forone or more years). Most broadleaved trees, such as oaks, maples and hickories, aredeciduous. Most cone-bearing trees, such as pines, spruces, firs and hemlocks, andsome broadleaf trees, such as American holly and live oak, are evergreen.When a tree has shed its leaves, identification can be more difficult. You must thenrely on the bark, twigs and buds, and any fruit or flower parts remaining on the tree tomake identification. Knowing these characteristics will help you identify trees duringthe late fall, winter and early spring months.A scientific key is a useful tool for identifying trees. The key in this book isdichotomous; that is, it gives the user two choices at each step. To use the key,always start with number one. Read both statements and choose the one that bestfits your tree. Each choice you make will direct you to another numbered pair ofstatements. Continue to follow the numbers until you arrive at the name of a tree.Once you have the name, go to the page listed to see a picture and learn moreinformation. It is most helpful to use this key in the field, where you can easilysee features, such as the bark and the growing site. If you need to identify a treeand you don’t have the key with you, take good notes or make sketches so thatyou can remember important features later. Keys are not perfect, and individualtrees may vary. If you don’t get acorrect identification with the key, tryagain, as it is possible to make anincorrect choice at some stage in theprocess. If the tree simply will not“key out,” it may be a non-native orless common species not coveredin the scope of this book. You canfind a more comprehensive key inmost dendrology textbooks, or try theinteractive online key at he following illustrations show someof the characteristics you will needto observe as you use the key. Inaddition, the glossary at the back ofthis book should define any confusingor technical terms you find in the key.10Northern Red Oak

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideIdentification of Trees, continuedParts, Types and Positions of LeavesScale-like(Redcedar)Needle-like(White Pine)Palmately Lobedand Veined(Red Maple)Pinnately Lobedand Veined(White Oak)Palmately Compound(Yellow Buckeye)Pinnately Compound(Green Ash)LeafletMidribBladeRachisPetiole11

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideIdentification of Trees, continuedTypes of Leaf yToothedIncurvedTeethBluntlyToothedLeaf PlacementTerminal (end) BudLateral (side) BudOppositeLenticels (pores)Leaf ScarAlternatePith12Lobed

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideLandscaping With FirewiseTree SpeciesIn Virginia, the expanding wildland-urban interface consists ofwww.firewisevirginia.orgmany homes adjacent to fire-prone natural areas. To be “firewise”is to be adequately prepared for the possibility of wildfire. Firewise has manycomponents including community design, escape routes and plans, constructionmaterials and landscaping around a home.The creation of defensible space is a landscape strategy for reducing the risk ofdamage from wildfires. Defensible space surrounding a home allows for easy accessby firefighting equipment and personnel, but also increases the chance of a homesurviving even if firefighters are unable to reach each home.In high-risk areas, creating defensible space generally includes vertical and horizontalseparation of plants surrounding a home. Branches of trees should be separatedfrom plants beneath them by at least 10 feet. There should also be at least a 10foot separation between branches of individual trees, and between branches andstructures. Landscape plantings should be grouped into isolated landscape islandsseparated by less flammable materials such as maintained lawn, pathways or gravel.Any landscape beds next to a home should consist of sparse, low-growing groundcover separated from the home by gravel or stones with no flammable landscapingmaterials in contact with the home. Plant arrangement is one of the most importantfactors affecting the survivability of a home during a wildfire.Although some plants are more fire-resistant than others, THERE ARE NO FIREPROOF PLANTS. UNDER EXTREME FIRE CONDITIONS, ALL PLANTS WILLBURN! A general flammability rating has been placed on the trees listed in thispublication. These ratings can help you make sound landscaping choices andsubsequently create a Firewise Landscape around your woodland home.Flammability of the SpeciesEXTREME (not firewise): These species should be avoided in landscaping within 100feet of your home.HIGH (at-risk firewise): These species could be placed in the landscape beyond(greater than 50 feet) the defensible space surrounding your home.MODERATE (moderately firewise): These species can be placed within the zone from30 to 50 feet from your home. Routine maintenance is needed to keep the plant lessflammable.LOW (firewise): These species have no known characteristics of high flammability.These species are appropriate for placement within your defensible space.For more information, visit www.firewisevirginia.org or contact your local VDOF office.13

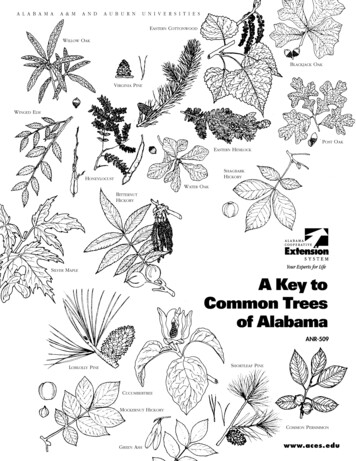

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideKey to Common Native Trees of VirginiaAlways start with number one. Read both a and b, choose the one that best describesyour tree, and go to the number where your choice directs you. Continue readingchoices and following the numbers until you reach the name of a tree. Turn to thepage indicated, and compare the picture and description to verify the tree’s identity.1a. Leaves are needle or scale-like, go to 2.b. Leaves are broad and flat, go to 14.2a. Needles at least 1 inch long, go to 3.b. Needles less than 1 inch long or scale-like, go to 10.3a. Needles in groups of 5, and 3 to 5 inches long – Eastern White Pine, pg. 22.b. Needles in groups of 2 or 3, go to 4.4a. Needles mostly in groups of 3, go to 5.b. Needles mostly in groups of 2, go to 8.5a. Needles generally longer than 6 inches, go to 6.b. Needles generally shorter than 6 inches, go to 7.6a. Needles 6 to 9 inches, cones 3 to 6 inches long – Loblolly Pine, pg. 24.b. Needles 8 to18 inches, cones 6 to10 inches long – Longleaf Pine, pg. 25.7a. Needles 3 to 5 inches, yellow-green, stiff and twisted. Found in Appalachianmountain range – Pitch Pine, pg. 26.b. Needles 4 to 8 inches, green to yellowish-green. Found in Coastal Plain –Pond Pine, pg. 28.8a. Needles 3 to 5 inches, dark yellow green, cones 1½ to 2½ inches long –Shortleaf Pine, pg. 23.b. Needles less than 3 inches, go to 9.9a. Needles 1½ to 3 inches, yellow-green and twisted, cones 1½ to 3 inches long.Scaly bark on older trees, may be orange-brown on upper trunk and largelimbs – Virginia Pine, pg. 27.b. Needles 1½ to 2½ inches, dark green, and somewhat twisted, cones 2 to 3½inches – Table Mountain Pine, pg. 29.10 a. Most needles not scale-like, and at least ⅓ inch long, go to 11.b. Most needles scale-like and less than ⅓ inch long, go to 13.11 a. Needles 4-sided, sharp, and dark yellow-green, extending from the branch inevery direction – Red Spruce, pg. 30.b. Needles flat, extending only to the sides of the branch, go to 12.12 a. Needles are deciduous, bark reddish brown, fibrous and shreddy. Found inCoastal Plain swamps or bottomlands – Baldcypress, pg. 32.b. Needles not deciduous, with 2 parallel white lines on the underside of the14

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideKey to Common Native Trees of Virginia, continuedneedles. Found in western Piedmont and mountains – Eastern Hemlock, pg.31.13 a. Young needles prickly, up to ⅜ inch long, older needles scale-like, 1/16 inchlong, bark tan to reddish brown and shreddy. Bluish fruit ⅛ inch in diameter –Eastern Redcedar pg. 35.b. Needles scale-like, 1/16 to ¼ inch long and flattened against twig. Very fragrant– Northern White-cedar pg. 34 or Atlantic White-cedar pg. 33.14 a. Leaves opposite, go to 15.b. Leaves alternate, go to 25.15 a. Leaves compound, go to 16.b. Leaves simple, go to 19.16 a. Leaves are pinnately compound, go to 17.b. Leaves are palmately compound – Yellow Buckeye pg. 91.17 a. Leaflets with large teeth, twig covered with whitish wax, bud covered with softwhite hairs – Boxelder pg. 86.b. Leaflets with small teeth, twig not covered with wax, bud not covered withhairs, go to 18.18 a. Leaflets toothed from midway up edge to tip, and underside covered withwhitish wax – White Ash pg. 98.b. Leaflets toothed from base to tip and fuzzy underneath; often found near water– Green Ash pg. 99.19 a. Leaves not lobed, go to 20.b. Leaves lobed, go to 21.20 a. Leaves less than 6 inches long, edges not lobed or toothed, bark blocky –Flowering Dogwood pg. 93.b. Leaves more than 6 to 16 inches long, may be coarsely toothed, 3 lobed, orheart shaped – INVASIVE Royal Paulownia pg. 103.21 a. Leaf edges toothed, go to 23.b. Leaf edges not toothed but with wavy points, and leaf generally 5 lobed, go to22.22 a. Veins and petiole secrete milky white sap when broken, seed pod flat with awing – INVASIVE Norway Maple pg. 104.b. No milky white sap in petiole or veins, seed pod round with a wing – SugarMaple pg. 87.23 a. Leaves three-lobed, young stems and bark green with white stripes – StripedMaple pg. 90.b. Young stems not green with white stripes, go to 24.15

Common Native Trees of Virginia Tree Identification GuideKey to Common Native Trees of Virginia, continued24 a. Leaves three or five lobed with shallow sinuses, twigs odorless whenscratched – Red Maple pg. 88.b. Leaves five lobed with deep, rounded sinuses, green above and white orsilvery below. Twig has bad odor when scratched – Silver Maple pg. 89.25 a. Leaves compound, go to 26.b. Leaves simple, go to 36.26 a.Leaflets oval or oblong and less than 2 inches long, twigs have thorns, go to27.b. Twigs do not have thorns, go to 28.27 a. Leaves singly compound, thorns in pairs on either side of buds, leaflet edgenot toothed, deeply furrowed bark, and seed pods 2 to 5 inches long – BlackLocust pg. 84.b. Leaves singly or doubly compound, leaflet ½ to

professional foresters, biologists, and other resource specialists. Subjects include forest ecology and management; timber harvesting and reforestation; tree identification and measurement; wildlife management and habitat improvement, and environmental protection. Additional activities include field trips, demonstrations, exploratory