Transcription

Rethinking Strategic PlanningPart I:Pitfalls and FallaciesHenry Min tz bergSo CALLED ‘STRATEGIC PLANNING’ ARRIVED on thescene in the mid 1960s with a vengence, boosted bythe popularityof Igor Ansoff’sbook CorporateStrategy,’publishedin 1965. Now, three decadeslater, if the conceptis not exactly dead, it hascertainly fallen from its exalted pedestal. Yet, in myopinion, the reasons for this are still hardly understood, which means that similar costly misadventures are likely to take place, under other labels.In the first of two articles on the rise and fall ofstrategic planning,based on a book by that title, Iconsider what went wrong and what we can learnfrom that experience,both about our managementprocessesand about ourselves.The second articlethen considers the lessons of this for planning, forplans, and for planners.An expert has been defined as someonewhoavoids all the many pitfalls on his or her way to thegrand fallacy. Plannersare experts of a sort, andsome of them have written extensivelyabout the‘pitfalls’ that undermine the practice of planning. Ibelievewe have somethingto learn from thesepitfalls, but not as they have been depicted in thisliterature.My intention,instead, is to turn themaround, to show that planning may be the very causeof the problem its proponents have tended to blameon everyone else. That will free the way to addressa set of fundamentalfallaciesthat I believe e to that one grand fallacy.Planning’sPresumedPitfallsA number of well publicizedstudies over the yearshave identified the ‘pitfalls’ of planning. Best known,Planners have tended ?o blame the pr&lems of socalled ‘strategic planning on a sat of ‘pitfalW-notab@the lack of tup management support and organizationalclimates not congenial ta planning. But planning maywell have discouragf?d the very support its praporMlt5claim to need, and its&f may have gener&ed climatesuncongenial to effective stratagy making. The realproblems may, therefara, lie deeper than these pitfalls,in a sat of what can be called ‘fallacies’, notably aboutthe capabilities of predicting discontinuities, aboutbeing ab#e to detach strategists from the subjects oftheir strategy making, and about being able to formalizethe strategy making process in the first @ace. Part oneof this two part article thus contzludes that ‘straiegicplanning’ is an oxymoron,perhapshas beenSteiner’ssurveyof severalhundred mostly large companies.” Here, as in otherstudies, two pitfalls stood out: the absence of topmanagementsupport for planning and a ‘climate’ inthe organizationnot congenial to planning. Table 1lists Steiner’s ten main pitfalls; arguably, six or sevenof them relate to these two (numbers, 1, 2, 4, 7, 10and perhaps 9 to the first, 6 to the second).In a way pitfalls are to planning what sins are toreligion: impedimentsto be brushed aside, cosmeticblemishes to be removed, so that the nobler work ofserving the almighty can proceed. Except that theplanning pitfalls are committedmostly by ‘them’,not ‘us’. Inattentivemanagersand dysfunctionalorganizationsare the sinners, not the planners themselvesor theirsystems.To quoteAbel1 andHammond, ‘The underlying causes of [the] problems[of making planningwork] are seldom anuingVol.CopyrightI’rintc!din Great27.0No.3, pp.12 to 21,1994ElscvierBritain.All0024 6301/941994SciencerightsLtdreserveds7.00 .00

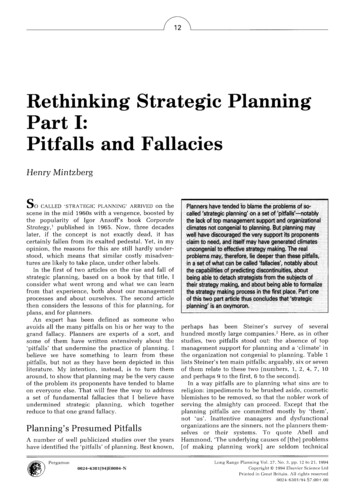

TABLE7. the pw&& of cwpcmf&3 ptmhgDescription7. Top management’sassumption that it can delegatethe planning function to a planner.2. Top managementbecomes so engrossed in currentproblems that it spends insufficient time on longrangeplanning,and the processbecomesdiscredited among other managers and staff.Failure to develop company goals suitable as a basisfor formulating long-range plans.Failure to assume the necessary involvementplanning process of major line personnel.Failing to use plans as standardsagerial performance.for measuringFailure to create a climate in the companycongenial and not resistant to planning.in theman-whichisAssuming that corporate comprehensiveplanning issomethingseparate from the entire managementprocess.8. Injecting so much formality into the system that itlacks flexibility,looseness, and simplicity, and restrains creativity.9. Failure of top managementto review with departmental and divisional heads the long-rangeplanswhich they have developed.10. Top management’sconsistently rejecting the formalplanning mechanismby making intuitive decisionswhich conflict with the formal plans.Source: G. Steinerdeficiencieswith the planningprocessor theanalytical approaches.Instead they are human andadministrativeproblems’,and ‘have as their sourcethe nature of human beings’.3 What this seems tomean is that ‘the systems would have worked fine ifit weren’t for all those darn people’. But unlessorganizationsare willing to get rid of the people forthe sake of planning, we had better find other waysto explain planning’s problems.More has been heard about the top managementsupport pitfall than any other. Yet surely no management technique has ever had more top managementsupport than strategicplanning.At the GeneralElectricCompany,for example,the best knownstrategic planning system in America was scuttled inthe early 1980s when Jack Welch took over as chiefexecutive. Did Welch know something that Steiner,Abel1 and Hammond did not? Indeed, had strategicplanning previously had too much top managementsupport at General Electric?As for that climateuncongenialto planning,might such a climate not sometimes be congenial tooverall organizationaleffectiveness?Can a climate,for example, be congenial to important change yethostile to planning? Put differently, is a climate conducive to strategic planningnecessarilyone conducive to effective strategic thinking and acting?In pursuing these alternate themes, I shall use arather narrow definitionof planning,necessaryinmy view. I define planning as formalized procedureto produce articulatedresult, in the form of anintegrated system of decisions. In other words, planning is about formalization,whichmeansthedecompositionof a process into clearly articulatedsteps. Planningis thus associatedwith ‘rational’analysis.Of course, the word planning is often used morebroadly than this. To some people, going off to amountain retreat to talk about strategy is planning.There is no problem with this, in principle, exceptthat when planningis defined so broadly that itbecomessynonymouswith management,why isthere need for the separate word? As Wildavsky putit in the title of an article, ‘If Planning is Everthying,Maybe It’s Nothing’.4 In practice, however, there is aserious problem.Implicitly,when not explicitly,there is an underlying sense of formal rationality tothe word. Call it ‘planning’ and suddenly things getsystematized-agendasget set, processes get decomposed (‘We shall discussgoals in the morning,strengthsandweaknessesin theafternoon’),schedulesget established(‘CorporateStrategy by5 p.m.Tuesday,BusinessStrategyby noon onThursday’). Thus strategic planning does not meanstrategic thinking so much as formalizedthinkingabout strategy-rationalized,decomposed,articulated. With this in mind, let us reconsider the pitfallsof planning.The CommitmentPitfallThe issue is not simply whether management is committed to planning. It is also (a) whether planning iscommitted to management,(b) whether commitmentto planning engenders commitment to strategies andto the process of strategy making, and (c) whetherthe very nature of planning actually fosters managerial commitment to itself. I propose to answer each ofthese questions in the negative.Compare a committing style of managementwitha calculatingstyle .5 The former engagespeoplein the journey.It finds a route, and developsLong Range Planning Vol. 27June 1994

enthusiasmin travelling it. The latter fixes on thedestinationand calculates back. It is often less thanengaging, because to be objective, as someone onceremarked,all too often means to treat people asobjects. If anyone has doubts about which style planning tends to favour, considerhow Igor Ansoffdescribed it back in 1964:methodologyis a successionof differencereduction steps: a set of objecivesis identified for the firm,the current position with respect to the objectivesis diagnosed, and a differencebetween these (or what we calledthe ‘gap’) is determined.Then a search is institutedfor anoperator (strategy) which can reduce the gap. The operatoris tested for its ‘gap reducing’properties.If the propertiesare satisfactory(the gap is essentiallyclosed) the operatoris accepted; if the gap is partially closed the operator is provisionally accepted and an additional operator is sought; ifthe operator is marginal or negative in its ability to closethe gap, it is rejected and a new one is sought.‘,The underlyingWhat is sometimes not appreciated is that there is nosuch thing as an ‘optimal’ strategy, calculatedviasome formal process. Intended strategieshave novalue in and of themselves;to paraphrase the classicwords of Philip Selznick, they take on value only ascommitted people infuse them with energy.7The very purpose of strategic planning, no matterhow much lip service has been paid to the contrary,is to reduce the power of managementover strategymaking. This is the effect of formalization,and it isrevealed most clearly in the way intuition has traditionally been put down in the literature of planning.To quoteits most prolificcontributor,GeorgeSteiner: ‘If an organizationis managed by intuitivegeniuses there is no need for formal strategic planning. But how many organizationsare so blessed?And if they are, how many times are intuitivescorrect in their judgements?‘sClose behind Steinerin sheer volume of publicationsis Peter Lorange. Hehas written that ‘the CEO should typically not be . . .deeply involved’ in the process, but rather be ‘thedesigner of [it] in a general sense’.g If this is how topmanagers, and especially processes critical to them,are viewed by the best known writers in the field,then how is anyone to expect planning to engenderthe commitmentof top management?Elsewhere in the corporate hierarchy, the problembecomes more severe, because planning has oftenbeen used to exercise much more blatant controlover middle and lower levels of management.EvenAnsoff has commentedon that ‘strangelynaiveprescription’that, ‘If managers [at lower levels] doRethinkingStrategicPlanningPart I: Pitfallsand Fallaciesnot plan willingly,threatenthem with the displeasureof the big boss and tell them he lovesplanning’.“’No wonderthe headof entlyto a BusinessWeek reporter after theWelch changes about ‘grabbing hold’ of his businessfrom ‘an isolated bureaucracy’of planners.”All hewantedwas personalcommitmentto his ownstrategy, for which he had to fight the planners!The Change PitfallA climate congenial to planning is considered to beone congenial to serious change in an organization.The reality, however,may well be that planningimpedes more than promote such change, therebydestroying the very climate it claims to require.The purpose of a plan is to render things inflexible, that is, to set the organization on a course ofaction. Plans may not engender human commitment,but they do commit organizations.A ‘flexible plan’,like a Progressive Conservative (or a civil engineer?],is thus an oxymoron:planningby directionhas to be inflexible.Once theplanners have made the thousandsof calculationsthat arenecessaryto fit the plan together,and have issued theirdirections,any demand that any of the figures be revised isbound to be resisted.That plan once made must beadhered to simply because you cannot alter any part of itwithout altering the whole, and altering the whole is tooelaborate a job to be done frequently.‘2Even the process of planning itself tends to evokeresistance to serious change in organizations.That isbecause of its need for decomposition,which tendsto happen in terms of the establishedcategories ofthe organization-forexample, the existing levels ofstrategy(corporate,business,functional)or theestablishedproducttypes (definedas ‘strategicbusinessunits’), overlaid on the current units ofstructure(divisions,departments,etc.). But realstrategic change generally means the rearrangementwhich must often leave planningof categories,behind, concerned only with incrementalchange.In fact, planning tends to promote change that isgenericrather than creative,simply synthesis. Put another way, it is creativity, by definition, that rearranges the established categories; planning, in contrast,by its very nature uses and sothesecategories.Thereare certainlypreserves

creative plannersaround-thatis, creative peoplewith the title planner-butthat has nothing to dowith the technology or processes of planning.As a result, a relianceon planningtends topromote strategiesthat are extrapolatedfrom thepast or copied from others. ‘In science, as in love’,on techsomeone once quipped’, a concentrationnique is likely to lead to impotence’.Search all pposedlygiveconnectedboxesYoustrategies-andnowhere will you find a single onethat explains the creative act of synthesizingideasinto a strategy. Everything can be formalized exceptthe very essence of the process itself.Moreover,despite its claims, planning tends tofavour short term change over long, simply because,as I shall discuss later, its methods of forecasting,especiallyof discontinuities,are weak. Visionariescan sometimeslook far and wide; planning techniques, in contrast, can see neither very far aheadnor easily off to either side. In addition, the very factof having to tie strategic planning to budgeting, ascalled for in the models, focuses attention on theshort term. The long term simply does not count inmost real-worldplanning,figurativelyas well asliterally.The Politics PitfallA climate of political activity messes up the orderlyworld of planning, according to a conventionalpitfall. In fact, however, planningdoes its share tobreed certain political activities, while other politicalactivitiessometimesdo their share to foster progressive change in organizations,despite planning!Planning is typically described as objective.Butthat, in fact, proves to be a biased form of objectivity.For one thing, planners are biased like the rest ofus-intheir case about planningitself and abouttheir own influence over strategy making, to be sure,but also about the goals that they implicitly favour inthe organization.A bias in favour of objectivity,forexample, means, as we have already seen, the favouring of analytic processes over intuitive ones-thosethat can be formally decomposed,articulated, and soformallyreplicatedand verified.Moreover,asalready discussed,planningintroducesa bias infavour of incrementalchange, of generic strategies,and of goals that can be quantified(so that, forexample, in one study of capital budgeting, typically,hard-to-quantifycosts and benefits were excludedfrom the financial analysis’).13 Thus, the popularityof strategic planning may well have favoured socalled cost leadership strategies over ones of productleadership, simply because innovative design or highquality are more difficult to measure and formalizethen straight cost cutting.If planning is biased, it is bound to breed politicalresistance,if only from people who represent otherbeliefs-forrevolutionarychange, for example,orcreative strategies, or innovative product designs . . .or simple good old-fashionedintuition. When planners put down the informal processes of managers,when they discouragecommitmentin favour ofcalculation,when they act as watchdogsfor the‘correct’ practices of middle managers, they aggravate the classic political conflict between line andstaff. Thus can they promote the very climate theyfind so uncongenialto planning.Finally, politics itself can sometimes have a positive effect on an organization,despite planning.When planning favours something close to the statusquo, while the organizationneeds radical change,then political challengeof planning and other setprocedures may be the only way to get it. Put differently, politics, like intuition,can be a viable andeven preferablealternativeto planning for gettingthings done in organizations.These, to my mind, are the true pitfalls of strategicplanning.But its real problems lie deeper. I shalldiscuss three, in particular, as ‘fallacies’, in conclusion, reducing them to that one grand fallacy.The Fallacy of PredeterminationTo engage in planning, an organization must be ableeither to controlits environment,to predict itscourse, or simply to assume its stability. Otherwise,it makes no sense to set the inflexiblecourse ofaction that constitutes a plan.Igor Ansoff wrote in Corporate Strategy in 1965,that ‘We shall refer to the period for which the firm isable to construct forecasts with an accuracy of, say,plus or minus 20 per cent as the planning horizon ofthe firm’.14 A most extraordinary statement from oneof the most popular books on planning ever! For howin the world can any firm know the period for whichit can forecast with a given accuracy, let alone be soLong Range Planning Vol. 27June 1994

sure of doing the forecastingitself?! How, in otherwords, can predictabilitybe predicted?The evidence on forecasting is, in fact, quite to sonal) may be predictable,the forecastingof discontinuities,such as technologicalinnovationsorprice increases, is, according to Spiros Makridakis, aleading expert in the field, ‘practicallyimpossible’.In his opinion, ‘very little, or nothing’ can be done,‘other than to be prepared, in a general way, to . . .react quickly once a discontinuityhas occurred’.‘”And if such events cannot be predicted,the onlyhope for planning is to ensure that none of consequenceswill occur and so simply to forecast byextrapolation.But that hope does not amount tomuch given another conclusionof Makridakis,in areview article with Hogarth, that, ‘Long-rangeforecasting(two years or longer)is notoriouslyinaccurate’.l”Of course, informally,certain people can sometimes ‘see’ things coming. That is why we call them‘visionaries’.But they create their strategies in a verydifferentway, morepersonalized,or intuitive.Strategy here takes on the sense of a broad perspective, a general (and not too preciselyarticulated)vision of direction.The problem with planning is that it needs thatarticulationand precision-ofstrategy as well as ofthe conditionsin which it is embedded.It has tohave not only predictabilityfollowing,but alsostability during strategy making. In other words, theworld is supposed to hold still while the planningprocess proceeds.Hence those lockstopplanningschedules that have strategies appearing on, say, thefirst of June, to be approved by the board of directorson the fifteenth. One can just picture the competitorswaitingfor the sixteenth(especiallyif they areJapanese,and do not much believe in such planning!).In fact, the conceptof strategyitself impliesstability,whetherin the plans intendedor thepatterns realized. l7 Planning fits quite well with this,as it too is designed to stabilize behaviour. But thesubjecthere it not strategy so much as strategymaking, and that takes place preciselywhen theworld does not hold still, or has not held still. This,in other words, is a dynamic process, associated withchange, and usually significantand discontinuouschange at that-thevery conditions most uncomfortable for planning.Rethinking Strategic Planning Part I: Pitfalls and FallaciesStrategiesare not developedon schedule,immaculately conceived.They can appear at any timeand at any place in the organization,typicallythrough processesof informal learning more thanones of formal planning.If strategiesrepresentstability, then strategy making is interference,andno amount of protest by planners about ‘management by crisis’ will ever change this. The simple conclusion, to which we shall return, is that strategicplanningis actuallyincompatiblewith seriousstrategy making.The Fallacy of DetachmentMarianne Jelinek developed the interestingpoint ina book titled s to the executivesuite whatFrederickTaylor’s work study was to the factoryfloor-away to circumventhuman idiosyncraciesin order to systematizebehaviour.‘It is throughadministrativesystems that planning and policy aremade possible, because the systems capture knowbyledge about the task . .’ Thus, ‘true managementexception,and true policydirectionare nowpossible,solely because managementis no longerwholly immersed in the details of the task itself’.‘”If the system does the thinking, then thought hasto be detached from action, strategy from operations(or ersfrom doers, and so strategistsfrom theobjects of their strategies. Managers must, in otherwords, manageby remote control.Thus Jelinekrefers to ‘the large-scalecoordinationof detailsplanningand policy-levelthinking,aboveandbeyond the details of the task itself’.‘”The trick, of course, is to get the relevant information up there, so that those senior managers on highcan be informed about those details without havingto enmesh themselvesin them. But that poses noproblem: strategic planning is driven by ‘hard data’that aggregates of the detailed ‘facts’ aboutthe organizationand its context, neatly packaged forimmediateuse. To return to Jelinek,‘the systemfar beyondits originalgeneralizesknowledgediscovereror discoverysituation’.‘”With all thenecessary data packaged convenientlyand deliveredregularly, senior managers need never get off thepedestal that planning puts them on, nor need plan-

ners leave the comfort of their staff offices. Togetherthey can formulate-workwith their heads-sothatall the other hands can then get on with theimplementation.I maintain that all of this is dangerously fallacious.Detached managers together with abstractedplanners do not so much make bad strategies;mostlythey do not make strategies at all. Look inside allthose companies crying for a strategic vision, amidstall their strategic planning, and you will mostly findexecutiveswho are detached from the very thingsthey are supposed to make strategy about. They aredoing exactly what planning tells them to do.The popular metaphor is that managers have tosee the forest rather than the trees. But from ahelicoptera forest looks like an artificial carpet ofgreen, not the complex living system it truly is. Eventimber company managers have to get down on theforest floor to look carefully at individual trees. Abetter metaphor,therefore,may be to find thediamond in the rough. In other words, real strategists get their hands dirty digging for ideas, whilereal strategies are built from the occasional nuggetsthat are uncoveredin this way. Put differently,effectivestrategistsare not people who abstractthemselvesfrom the daily detail but quite theopposite: they immerse themselves in it while beingable to abstract the strategic messages from it. Thetrouble with the distinctionbetween strategies andtactics is that it becomes clear only after things havehappened-justask that general who lost the battlebecause of the nail in his horse’s shoe. Again thearbitrarycategoriesof planningimpede effectivestrategy making.At the infamous World World I Battle of Passchendaele-describedas ible’-the‘great plan’ that ‘wascomplete’ before the battle began failed to accountfor the steady rains that subsequentlycame. And soa quarter of a million British troops fell. ‘No seniorofficer . . . it was claimed, ever set foot (or eyes) onthe . . . battlefield during the four months that battlewas in progress . . . Only after the battle did theArmy Chief of Staff learn that he had been directingmen to advance through a sea of mud’.z1 What is itabout planningthat so blindsus to unfoldingevents?It turns out that hard data-forexample,theformalreportsof the Passchendaelebattlefield,which were ‘first ignored,then ordered discon-tinued’-canhave a decidedly soft underbelly. Theytake time to harden, which often makes them late;they tend to lack richness, for example excluding thequalitative,which can render them ineffectiveforpurposes of diagnosing the cause of problems; andthey tend to be overly aggregated, which can causethem to miss importantnuances.22 These are thereasons why managers who rely on formalized information (such as marketing research reports, opinionpolls, and the like, as well as accounting statements),tend to be detached in more ways than one, and whyeffective managers have been shown in study afterstudy to rely on some of the softest forms of information available, including gossip, hearsay, and varioustangible scraps of information.In fact, it is planning’s very predispositionto harddata that detaches planners from strategy makingas it does those senior line managers who take itseriously. As already noted, strategy making is reallya visionary as well as a learning process. But vision isunavailable to those who cannot ‘see’ with their owneyes-whocannot observe the world directly, as it is,instead of having to look at it through filters. Andlearning is inductive:it happens when details areuncovered from which general conclusions can be inferred-thosetrees in the forest, that diamond in therough. The ‘big picture’, in other words, has to bepainted by little strokes, many of them initially fuzzy.Effective strategy making thus connects acting tothinking which, in turn, connects implementationtoformulation. We think in order to act, to be sure, butwe also act in order to think. We try things, andwhen something works, our experimentsgraduallyconverge into viable patterns that become strategies.This is not some quirky behaviourbut the veryessence of the process of strategic learning (that evensome more progressiveplannershave come tofavour).2”The whole thrust of the strategic planning exerciseis to separateformulationfrom implementation,thinking from doing. Senior managers aided by planners and their systems think while everyone elsedoes. Then when the strategies fail, as they so oftendo, the thinkers blame the doers. ‘If only you dumbbells understood our beautiful strategy . . . ’ But ifthe dumbbells were smart, they would reply: ‘If youare so smart, why didn’t you formulate a strategythat we dumbbellscould implement.’In otherwords, every failure of implementationis also, bydefinition, a failure of formulation.Long Range Planning Vol. 27June 1994

But I would argue that the true fallacy goesbeyond this: it is the failure of the very separationbetween formulationand implementation,thinkingand doing. It lies in the misguidedmetaphor,sopopular in the planning literature but in fact datingright back to FrederickTaylor, that organizationshave heads, or ‘tops’, by which to think, and bodiesor ‘middles’ and ‘bottoms’ by which to act.In contrast, the visionary and learning approachesto strategy making break down this dichotomybyallowingimplementationto informformulation.This can happen in two ways, one more centralized,the other more decentralized.In the former, theformulator,namely the visionary,connectshim orherself intimately to the implementation,managingmany of the details personally as they unfold, so asto adapt and elaborate the vision en route. In theother, the so-called implementersbecome formulators, by pursuing the strategic consequencesof theirspecificexperiments.Either way, the processofstrategy making becomes less artificiallydetached,more richly interactive.Thus, when we are talkingabout the process of creating viable strategy, we hadbetter drop the phrase strategic planning altogetherand talk instead about strategic thinking connectedto acting.The Fallacy of FormalizationCan the systems in fact do it? Can ‘strategic planning’, in the words of a Stanford Research Instituteeconomist,‘recreate’the processof the ‘geniustechentrepreneur ‘?24 ‘I favour a set of analyticalniquesfor developingstrategy’,MichaelPorterwrote in The Economistmore recently.2” But cananalysis provide synthesis?Note that strategicplanninghas not generallybeen presented as an aid to strategy making, or assupport for natural managerial processes (includingintuition),but as the former and in place of thelatter. It is claimed to be proper practice-toborrowFrederickTaylor’s favourite phrase, the ‘one bestway’ to create strategy.There is an interesting irony in this, because planning missed one of Taylor’s most important messages. Taylor was careful to note that work processeshave to be fully understoodbefore they can beformally programmed.His own accountsdwell onthis at great length. x But where in the planningRethinkingStrategicPlanningPart I: Pitfalls and Fallaciesliteratureis there a shred of evidencethat theauthors ever botheredto find out how it is thatmanagersreally do make strategy? Instead it wasmerely assumed that strategicplanning,strategicthinking, and strategy making were all synonymous,at least in best practice.The CEO ‘can seriouslyjeopardize or even destroy the prospects of strategicthinking by not consistentlyfollowing the disciplineof strategic planning’, wrote Lorange in 1980 with nosupport whatsoever.27The facts are, first, as already noted, that none ofthose fancy planning charts ever contained a singlebox that explainedhow strategy is actually to becreated-howthe synthesisof those genius entrepreneurs, or even ordinary competent strategists,isto be recreated. Second, a great deal of study, muchof it by researchersfavourable to the process, thatsought to prove that planning pays, never did proveanythingof the kind. 28 Indeed a great deal ofanecdotalevidencein the popular businesspresssuggests exactly the opposite conclusion.(And whoever met a middle manager enthusiasticabou

Thursday'). Thus strategic planning does not mean strategic thinking so much as formalized thinking about strategy-rationalized, decomposed, articu- lated. With this in mind, let us reconsider the pitfalls of planning. More has been heard about the top management support pitfall than any other.