Transcription

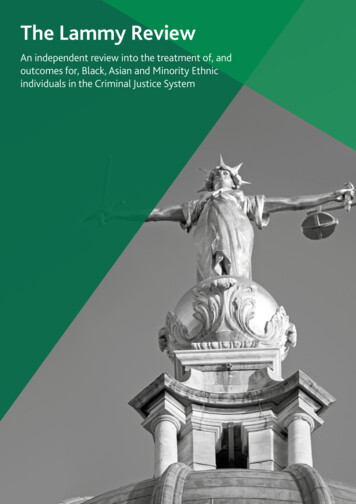

The Lammy ReviewAn independent review into the treatment of, andoutcomes for, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnicindividuals in the Criminal Justice System

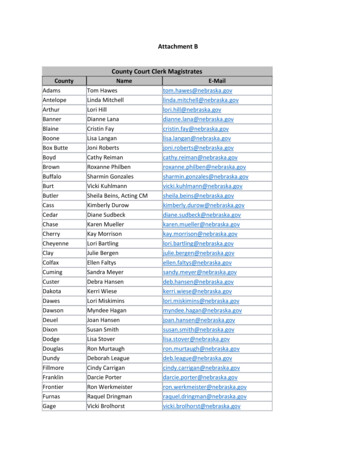

Lammy ReviewContentsIntroduction2Chapter 1: Understanding BAME disproportionality10Chapter 2: Crown Prosecution Service16Chapter 3: Plea Decisions24Chapter 4: Courts30Chapter 5: Prisons44Chapter 6: Rehabilitation56Conclusion68Annex A – Terms of reference72Annex B – Call for Evidence74Annex C – Glossary of Terms76Annex D – Lammy Review Expert Advisory Panel78Annex E – Fact Finding Visits80Annex F – Acknowledgments82Endnotes881

Introduction2

Introduction / Lammy ReviewAcross England and Wales, people from minority ethnicbackgrounds are breaking through barriers. More studentsfrom Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) backgroundsare achieving in school and going to university.1 There is agrowing BAME middle class.2 Powerful, high-profileinstitutions, like the House of Commons, are slowlybecoming more diverse.3 Yet our justice system bucks thetrend. Those who are charged, tried and punished are stilldisproportionately likely to come from minority communities.Despite making up just 14% of the population, BAME menand women make up 25% of prisoners,4 while over 40%of young people in custody are from BAME backgrounds.If our prison population reflected the make-up of Englandand Wales, we would have over 9,000 fewer people inprison5 – the equivalent of 12 average-sized prisons.6 Thereis greater disproportionality in the number of Black peoplein prisons here than in the United States.7These disproportionate numbers represent wasted lives, asource of anger and mistrust and a significant cost to thetaxpayer. The economic cost of BAME overrepresentationin our courts, prisons and Probation Service is estimated tobe 309 million a year.8This report is the product of an independent review,commissioned by two Prime Ministers.9 The review wasestablished to ‘make recommendations for improvementwith the ultimate aim of reducing the proportion of BAMEoffenders in the criminal justice system’.10 It reflects agrowing sense of urgency, across party-political lines, tofind solutions to this inequity.The ReviewThis review has two distinctive features, the first of whichis its breadth. The terms of reference span adults andchildren; women and men. It covers the role of the CrownProsecution Service (CPS), the courts system, our prisonsand young offender institutions, the Parole Board, theProbation Service and Youth Offending Teams (YOTS). Acomprehensive look at both the adult and youth justicesystems was overdue.Secondly, whilst independent of the government, thereview has had access to resources, data and informationheld by the criminal justice system (CJS) itself. In the past,too much of this information has not been made availableto outsiders for scrutiny and analysis. As a result, thisreview has generated analysis that breaks new ground onrace and criminal justice in this country.11The focus of the review is on BAME people, but I recognisethe complexity of that term. Some groups are heavily overrepresented in prison – for example Black people make uparound 3% of the general population but accounted for12% of adult prisoners in 2015/16; and more than 20%of children in custody.12,13,14 Other groups, such as Mixedethnic adult prisoners, are also overrepresented, althoughto a lesser degree.15 The proportion of prisoners who areAsian is lower than the general population but, withincategories such as ‘Asian’ or ‘Black’ there is considerablediversity, with some groups thriving while others struggle.This complexity mirrors the story in other areas of publiclife. In schools, for example, BAME achievement hasrisen but not in a uniform way. Chinese and Indian pupilsoutperform almost every other group, while Pakistanichildren are more likely to struggle. Black African childrenachieve better GCSE exam results, on average, than BlackCaribbean children.16 Wherever possible this report seeksto draw out similar nuances in the justice system.The review also addresses the position of other minoritieswho are overlooked too often. For example, Gypsies, Romaand Travellers (GRT) are often missing from publishedstatistics about children in the CJS, but according tounofficial estimates, are substantially over-represented inyouth custody, for example, making up 12% of childrenin Secure Training Centres (STC).17 Muslims, meanwhile,do not fall within one ethnic category, but the numberof Muslim prisoners has increased from around 8,900 to13,200 over the last decade.18 Both groups are consideredwithin scope for this review.I hope and expect that many of my recommendations willbenefit White working class men, women, boys and girlstoo. BAME communities face specific challenges, includingdiscrimination in many walks of life. But some of the mostmarginalised BAME communities have much in commonwith the White working-class. A justice system that worksbetter for those who are BAME and poor will work betterfor those who are White British and poor too.3

Lammy Review / IntroductionIn general, the areas of the CJS addressed in my report coverboth England and Wales. The laws on prisons and offendermanagement are reserved to Westminster, as is the singlelegal jurisdiction which covers courts, judges and criminalprocedure, including sentencing. However, in the contextof prisons and offender management there are someexceptions which are devolved to the Welsh Government.These include the legal provisions for health care in prisons;social care and education; training and libraries in prisons;and local authority accommodation for the detention ofchildren and young people.As far as possible I have sought to recommend actions thatI believe would benefit the CJS as a whole. I have not beenspecific about jurisdiction or the levers for implementation,other than in which part or agency of the justice systemthey should, or could, be owned and taken forward. Thework to implement my recommendations will need to bemindful of the differences in how the CJS is administeredin Wales.International contextThe problem is not unique to England and Wales. Over thecourse of this review I visited six countries and 12 citiesaround the world. In each jurisdiction, I found governmentsand civil society organisations grappling with how best toreduce racial disparities within their own criminal justicesystems. In France, Muslims make up an estimated 8%of the population and between a quarter and a half ofthe prison population.19 In America, one in 35 AfricanAmerican men are incarcerated, compared with one in 214White men.20 In Canada, indigenous adults make up 3%of the population but 25% of the prison population.21 InAustralia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisonersmake up 2% of the population, but 27% of prisoners.22 InNew Zealand, Maoris make up 15% of the population, butmore than 50% of the prisoners.23This report draws together the most promising ideas fromthose other jurisdictions; from efforts to diversify judiciariesto new ways of involving communities in rehabilitatingoffenders. In the chapters that follow I explore how theycan be applied in our own context. I also draw on ideasfrom closer to home, gathered through public consultationevents, an open call for evidence with over 300 responsesfrom a mix of organisations, experts, and private individuals;round-table seminars; and an intensive programme ofvisits to courts, prisons, probation services and communityinitiatives across England and Wales. I have spoken withthose who work in the system, from prison officers toprison governors, court clerks to our most senior judges.I have heard from victims and offenders, from faith groupsand charitable organisations, campaigners and academicexperts. Each of those perspectives has influenced theconclusions I have reached.4I present my findings and recommendations with onemajor qualification: many of the causes of BAME overrepresentation lie outside the CJS, as do the answersto it. People from a black background are more thantwice as likely to live in poverty than those from a whitebackground.24 Black children are more than twice as likelyto grow up in a lone parent family.25 Black and Mixed ethnicboys are more likely than White boys to be permanentlyexcluded from school and to be arrested as a teenager.26,27These issues start long before a young man or womanever enters a plea decision, goes before a magistrate orserves a prison sentence. Although these problems must beaddressed, this cannot be done by the justice system alone.Prisons may be walled off from society, but they remain aproduct of it.Nevertheless, our justice system is powerful and farreaching. It makes millions of decisions each year thatinfluence the fate of victims, suspects, defendants andoffenders. 1.6 million cases were received by our courtslast year, while billions are spent on supervising andrehabilitating offenders.28,29 More can be done to achievethe core goals of this review: to reduce the proportion ofBAME individuals in the CJS and ensure that all defendantsand offenders are treated equally, whatever their ethnicity.FindingsMy biggest concern is with the youth justice system. Thisis regarded as one of the success stories of the CJS, withpublished figures showing that, compared with a decadeago, far fewer young people are offending, reoffending andgoing into custody.30 YOTs were established by the 1998Crime and Disorder Act, with a view to reducing youthoffending and reoffending and have been largely successfulin fulfilling that remit. Yet despite this fall in the overallnumbers, the BAME proportion on each of those measureshas been rising significantly.31 Over the last ten years: The BAME proportion of young people offending for thefirst time rose from 11% year ending March 2006 to 19%year ending March 2016.32 The BAME proportion of young people reoffending rosefrom 11% year ending March 2006 to 19% year endingMarch 2016.33 The BAME proportion of youth prisoners has risen from25% to 41% in the decade 2006-2016.34 (see figure 1next page indicating the makeup of the youth custodialpopulation).35

Introduction / Lammy ReviewFigure 1: Under 18 secure population by ethnicity 2005/05 – 2017/18*2500WhitePopulation * 2016/17 and 2017/18 data is provisionalThe system has been far too slow to identify the problem,let alone to react to it. There are isolated examples of goodpractice, including in some YOTs36, but nothing serious orcomprehensive enough to make a lasting difference. Unlesssomething changes, this cohort will become the nextgeneration of adult offenders.In both the youth and adult systems, there is no singleexplanation for the disproportionate representation ofBAME groups. For example, analysis of 2014/15 data,shows that arrest rates were generally higher across allethnic groups, in comparison to the white group – twiceas high for Black and Mixed ethnic women, and were threetimes higher for Black men.37 Arrests are disproportionatebut this does not fully explain the make-up of our youthcustody population.Other decisions have important consequences. Forexample, analysis of the same 2014/15 data, shows thatBAME defendants were consistently more likely than Whitedefendants to plead not guilty in court.38 Admitting guiltcan result in community punishment rather than custody,or see custodial sentences reduced by up to a third.39 Pleadecisions are an important factor in the disproportionatemake-up of the prison system.In many prisons, relationships between staff and BAMEprisoners are poor. Many BAME prisoners believe they areactively discriminated against and this is contributing toa desire to rebel rather than reform. In the youth system,young BAME prisoners are less likely to be recordedas having problems, such as mental health, learningdifficulties and troubled family relationships, suggestingmany may have unmet needs. All this hinders efforts totackle the root causes of offending and reoffending amongBAME prisoners, entrenching disproportionality.41Probation services and YOTs are charged with managingoffenders in the community and helping them start newlives. However, our criminal records regime does preciselythe opposite of this. Over the last five years 22,000BAME children have had their names added to the PoliceNational Database.42 This includes for minor offences,such as a police reprimand. The result in adulthood is thattheir names could show up on criminal record checks forcareers ranging from accountancy and financial services toplumbing, window cleaning and driving a taxi.43There is evidence of differential treatment that is equallyproblematic. For example, analysis of sentencing data from2015 shows that at the Crown Court, BAME defendantswere more likely than White defendants to receive prisonsentences for drug offences, even when factors such as pastconvictions are taken into account.40 Despite some areasthat require further study, such as the role of aggravatingand mitigating factors, there is currently no evidencebased explanation for these disparities.5

Lammy Review / IntroductionKey principlesThe response to the disproportionate representationof BAME prisoners should be based around three coreprinciples: Firstly, there must be robust systems in place to ensurefair treatment in every part of the CJS. The key lessonis that bringing decision-making out into the open andexposing it to scrutiny is the best way of delivering fairtreatment. For example, juries deliberate as a groupthrough open discussion. This both deters and exposesprejudice or unintended bias: judgments must bejustified to others. Successive studies have shown thatjuries deliver equitable results, regardless of the ethnicmake-up of the jury, or of the defendant in question.44 This emphasis on opening decision-making to scrutinycan mean different things in different parts of thesystem. For example, the CPS has a system of randomlyreviewing case files, providing one model to replicate.Other examples include publishing data in much moredetail, thereby enabling outsiders to identify andscrutinise disproportionate treatment. Secondly, trust in the CJS is essential. The reason thatso many BAME defendants plead not guilty, forgoingthe opportunity to reduce sentences by up to a third,is that they see the system in terms of ‘them and us’.Many do not trust the promises made to them by theirown solicitors, let alone the officers in a police stationwarning them to admit guilt. What begins as a ‘nocomment’ interview can quickly become a Crown Courttrial. Trust matters at other key points in the CJS too.A growing international evidence base shows that whenprisoners believe they are being treated fairly, they aremore likely to respect rules in custody and less likely toreoffend on release.45 Trust is low not just among defendants and offenders,but among the BAME population as a whole. In bespokeanalysis for this review which drew on the 2015 CrimeSurvey for England and Wales, 51% of people fromBAME backgrounds born in England and Wales whowere surveyed believe that ‘the criminal justice systemdiscriminates against particular groups and individuals’.46The answer to this is to remove one of the biggestsymbols of an ‘us and them’ culture – the lack of diversityamong those making important decisions in the CJS;from prison officers and governors, to the magistratesand the judiciary. Alongside this, much more needs to bedone to demystify the way decisions are made at everypoint in the system. Decisions must be fair, but must alsobe seen to be fair, if we are to build respect for the ruleof law. Thirdly, the CJS must have a stronger analysis aboutwhere responsibility lies beyond its own boundaries.Statutory services are essential and irreplaceable, butthey cannot do everything on their own. The systemmust do more to work with local communities tohold offenders to account and demand that they takeresponsibility for their own lives. Local police forces forexample, have spent years working through the bestways to create dialogue and partnership with localcommunities, from neighbourhood policing approachesto Safer Neighbourhood Boards in every Londonborough. They are not perfect in every respect, but theydo represent progress. It is time for other parts of the CJSto do the same. For example, the youth justice systemshould be much more rooted in local communities,with hearings taking place in local neighbourhoods,using non-traditional buildings such as libraries orcommunity centres. Addressing high reoffending ratesamong some BAME groups, can only be done throughgreater partnership with communities themselves.Responsibility has a hard edge too. Behind manyyoung offenders are adults who either neglect orexploit them. The youth justice systems appear tohave given up on parenting. Last year, 55,000 youngoffenders were found guilty in the courts,47 but just189 parenting orders were issued by the youth justicesystem. Only 60 involved BAME young people.Parents need support alongside accountability.Many feel helpless about their children being exploitedand drawn into criminality. There is a settled narrativeabout young BAME people associating in gangs, but fartoo little attention is paid to the criminals who providethem with weapons and use them to sell drugs.48A concerted approach to these issues would focus moreattention and enforcement on the powerful adults muchfurther up criminal hierarchies. New tools like the ModernSlavery legislation must be used to hold these adults toaccount for the exploitation of our young people.ChaptersI explore these findings and reform principles in more detailin the following chapters: Chapter 1 sets out how ‘disproportionality’ is monitoredin the CJS and what must change in the future. Chapter 2 examines arrest rates and CPS charging decisions. Chapter 3 looks at plea decisions. Chapter 4 focuses on the courts. Chapter 5 addresses prisons. Chapter 6 tackles rehabilitation in the community.6

Introduction / Lammy ReviewFirst, though, I set out my recommendations in full below:Recommendation 1: A cross-CJS approach should beagreed to record data on ethnicity. This should enablemore scrutiny in the future, whilst reducing inefficienciesthat can come from collecting the same data twice. Thismore consistent approach should see the CPS and thecourts collect data on religion so that the treatment andoutcomes of different religious groups can be examined inmore detail in the future.Recommendation 2: The government should match therigorous standards set in the US for the analysis of ethnicityand the CJS. Specifically, the analysis commissioned forthis review – learning from the US approach – must berepeated biennially, to understand more about the impactof decisions at each stage of the CJS.Recommendation 3: The default should be for theMinistry of Justice (MoJ) and CJS agencies to publish alldatasets held on ethnicity, while protecting the privacy ofindividuals. Each time the Race Disparity Audit exercise isrepeated, the CJS should aim to improve the quality andquantity of datasets made available to the public.Recommendation 4: If CJS agencies cannot providean evidence-based explanation for apparent disparitiesbetween ethnic groups then reforms should be introducedto address those disparities. This principle of ‘explain orreform’ should apply to every CJS institution.Recommendation 5: The review of the Trident Matrix bythe Mayor of London should examine the way informationis gathered, verified, stored and shared, with specificreference to BAME disproportionality. It should bring inoutside perspectives, such as voluntary and communitygroups and expertise such as the Office of the InformationCommissioner.Recommendation 6: The CPS should take the opportunity,while it reworks its guidance on Joint Enterprise, to considerits approach to gang prosecutions in general.Recommendation 7: The CPS should examine how ModernSlavery legislation can be used to its fullest, to protect thepublic and prevent the exploitation of vulnerable youngmen and women.Recommendation 8: Where practical all identifyinginformation should be redacted from case informationpassed to them by the police, allowing the CPS to makerace-blind decisions.Recommendation 9: The Home Office, the MoJ and theLegal Aid Agency should work with the Law Society andBar Council to experiment with different approaches toexplaining legal rights and options to defendants. Thesedifferent approaches could include, for example, a role forcommunity intermediaries when suspects are first receivedin custody, giving people a choice between different dutysolicitors, and earlier access to advice from barristers.Recommendation 10: The ‘deferred prosecution’ modelpioneered in Operation Turning Point should be rolledout for both adult and youth offenders across Englandand Wales. The key aspect of the model is that it providesinterventions before pleas are entered rather than after.Recommendation 11: The MoJ should take steps to addresskey data gaps in the magistrates’ court including pleas andremand decisions. This should be part of a more detailedexamination of magistrates’ verdicts, with a particularfocus on those affecting BAME women.Recommendation 12: The Open Justice initiative shouldbe extended and updated so that it is possible to viewsentences for individual offences at individual courts,broken down by demographic characteristics, includinggender and ethnicity.Recommendation 13: As part of the court modernisationprogramme, all sentencing remarks in the Crown Courtshould be published in audio and/or written form. Thiswould build trust by making justice more transparent andcomprehensible for victims, witnesses and offenders.Recommendation 14: The judiciary should work withHer Majesty’s Courts and Tribunals Service (HMCTS) toestablish a system of online feedback on how judgesconduct cases. This information, gathered from differentperspectives, including court staff, lawyers, jurors, victimsand defendants, could be used by the judiciary to supportthe professional development of judges in the future,including in performance appraisals for those judges thathave them.Recommendation 15: An organisation such as JudicialTraining College or the Judicial Appointments Commissionshould take on the role of a modern recruitment functionfor the judiciary – involving talent-spotting, pre-applicationsupport and coaching for ‘near miss’ candidates. The MoJshould also examine whether the same organisation couldtake on similar responsibilities for the magistracy. Theorganisation should be resourced appropriately to fulfillthis broader remit.7

Lammy Review / IntroductionRecommendation 16: The government should set a clear,national target to achieve a representative judiciary andmagistracy by 2025. It should then report to Parliamentwith progress against this target biennially.Recommendation 17: The MoJ and Department of Health(DH) should work together to develop a method to assessthe maturity of offenders entering the justice system up tothe age of 21. The results of this assessment should informthe interventions applied to any offender in this cohort,including extending the support structures of the youthjustice system for offenders over the age of 18 who arejudged to have low levels of maturity.Recommendation 18: Youth offender panels should berenamed Local Justice Panels. They should take placein community settings, have a stronger emphasis onparenting, involve selected community members and havethe power to hold other local services to account for theirrole in a child’s rehabilitation.Recommendation 19: Each year, magistrates shouldfollow an agreed number of cases in the youth justicesystem from start to finish, to deepen their understandingof how the rehabilitation process works. The MoJ shouldalso evaluate whether their continued attachment to thesecases has any observable effect on reoffending rates.Recommendation 20: Leaders of institutions in theyouth estate should review the data generated bythe Comprehensive Health Assessment Tool (CHAT)and evaluate its efficacy in all areas and ensure that itgenerates equitable access to services across ethnic groups.Disparities in the data should be investigated thoroughly atthe end of each year.Recommendation 21: The prison system, working with theDepartment of Health (DH), should learn from the youthjustice system and adopt a similar model to the CHAT forboth men and women prisoners with built in evaluation.Recommendation 22: The recent prisons white paper setsout a range of new data that will be collected and publishedin the future. The data should be collected and publishedwith a full breakdown by ethnicity.Recommendation 23: The MoJ and the Parole Board shouldreport on the proportion of prisoners released by offenceand ethnicity. This data should also cover the proportion ofeach ethnicity who also go on to reoffend.8Recommendation 24: To increase the fairness andeffectiveness of the Incentives and Earned Privileges (IEP)system, each prison governor should ensure that there isforum in their institution for both officers and prisoners toreview the fairness and effectiveness of their regime. BothBAME and White prisoners should be represented in thisforum. Governors should make the ultimate decisions inthis area.Recommendation 25: Prison governors should ensureUse of Force Committees are not ethnically homogeneousand involve at least one individual, such as a member ofthe prison’s Independent Monitoring Board (IMB), with anexplicit remit to consider the interests of prisoners. Thereshould be escalating consequences for officers found to bemisusing force on more than one occasion. This approachshould also apply in youth custodial settings.Recommendation 26: Her Majesty’s Prison and ProbationService (HMPPS) should clarify publicly that the properstandard of proof for assessing complaints is ‘the balanceof probabilities’. Prisons should take into account factorssuch as how officers have dealt with similar incidents inthe past.Recommendation 27: Prisons should adopt a ‘problemsolving’ approach to dealing with complaints. As partof this, all complainants should state what they want tohappen as a result of an investigation into their complaint.Recommendation 28: The prison system should beexpected to recruit in similar proportions to the country as awhole. Leaders of prisons with diverse prisoner populationsshould be held particularly responsible for achieving thiswhen their performance is evaluated.Recommendation 29: The prison service should set publictargets for moving a cadre of BAME staff into leadershippositions over the next five years.Recommendation 30: HMPPS should develop performanceindicators for prisons that aim for equality of treatmentand of outcomes for BAME and White prisoners.Recommendation 31: The MoJ should bring together aworking group to discuss the barriers to more effectivesub-contracting by Community Rehabilitation Companies(CRCs). The working group should involve the CRCsthemselves and a cross-section of smaller organisations,including some with a particular focus on BAME issues.

Introduction / Lammy ReviewRecommendation 32: The Ministry of Justice shouldspecify in detail the data CRCs should collect and publishcovering protected characteristics. This should be writteninto contracts and enforced with penalties for noncompliance.Recommendation 33: The Youth Justice Board (YJB)should commission and publish a full evaluation of whathas been learned from the trial of its ‘disproportionalitytoolkit’, and identify potential actions or interventions tobe taken.Recommendation 34: Our CJS should learn from thesystem for sealing criminal records employed in many USstates. Individuals should be able to have their case heardeither by a judge or a body like the Parole Board, whichwould then decide whether to seal their record. Thereshould be a presumption to look favourably on thosewho committed crimes either as children or young adultsbut can demonstrate that they have changed since theirconviction.Recommendation 35: To ensure that the publicunderstands the case for reform of the criminal recordsregime, the MoJ, HMRC and DWP should commission andpublish a study indicating the costs of unemploymentamong ex-offenders.9

Chapter 1:Understanding BAMEdisproportionality

Chapter 1: Understanding BAME disproportionality / Lammy ReviewIntroductionSince the passage of the 1991 Criminal Justice Act,successive governments have published data on ethnicityand the criminal justice system (CJS). The purpose of thelegislation is to ‘avoid discriminating against any personson the grounds of race, sex or any other improper ground’.49It reflects a key principle of this review: scrutiny is the bestroute to fair treatment.This chapter argues that the CJS can do far more in thisarea. The CJS may be meeting its statutory obligations butit should be more ambitious than that: There are important gaps in what we know about theCJS. For example, prisons record inmates’ religion butthe courts and the CPS do not. This obscures importantquestions, like why the number of Muslim prisoners hasincreased by nearly 50% in the last ten years.50 This lackof transparency undermines accountability. The CJS should be world-leading in its analysis of ethnicity.This means learning from the methods used in the US toshine a spotlight on each part of the system. Specifically,the Relative Rate Index analysis commissioned for thisreview must be repeated and published on a regularbasis, to understand more about the impact of decisionsat each stage of the CJS. Accountability should come from outside the systemas well as from within it. This requires a new defaultposition: all the datasets held centrally on ethnicityand the CJS should be published, whilst protecting theprivacy o

In Canada, indigenous adults make up 3% of the population but 25% of the prison population. 21. In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners make up 2% of the population, but 27% of prisoners. 22. In New Zealand, Maoris make up 15% of the population, but more than 50% of the prisoners. 23