Transcription

Shiroma et al. Translational Psychiatry 97-0ARTICLETranslational PsychiatryOpen AccessA randomized, double-blind, activeplacebo-controlled study of efficacy, safety,and durability of repeated vs single subanestheticketamine for treatment-resistant ():,;1234567890():,;Paulo R. Shiroma1,2, Paul Thuras3, Joseph Wels4, C. Sophia Albott5, Christopher Erbes6, Susannah Tye7 andKelvin O. Lim8AbstractThe strategy of repeated ketamine in open-label and saline-control studies of treatment-resistant depressionsuggested greater antidepressant response beyond a single ketamine. However, consensus guideline stated the lack ofevidence to support frequent ketamine administration. We compared the efficacy and safety of single vs. six repeatedketamine using midazolam as active placebo. Subjects received either six ketamine or five midazolam followed by asingle ketamine during 12 days followed by up to 6-month post-treatment period. The primary end point was thechange from baseline in the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score at 24 h after the lastinfusion. Fifty-four subjects completed all six infusions. For the primary outcome measure, there was no significantdifference in change of MADRS scores between six ketamine group and single ketamine group at 24 h post-lastinfusion. Repeated ketamine showed greater antidepressant efficacy compared to midazolam after five infusionsbefore receiving single ketamine infusion. Remission and response favored the six ketamine after infusion 4 and 5,respectively, compared to midazolam before receiving single ketamine infusion. For those who responded, themedian time-to-relapse was nominally but not statistically different (2 and 6 weeks for the single and six ketaminegroup, respectively). Repeated infusions were relatively well-tolerated. Repeated ketamine showed greaterantidepressant efficacy to midazolam after five infusions but fell short of significance when compared to add-on singleketamine to midazolam at the end of 2 weeks. Increasing knowledge on the mechanism of ketamine should drivefuture studies on the optimal balance of dosing ketamine for maximum antidepressant efficacy with minimumexposure.IntroductionKetamine, a glutamate receptor–blocking drugapproved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration foranesthetic use, has become a target of research for itsCorrespondence: Paulo R. Shiroma (paulo.shiroma@va.gov)1Geriatric Psychiatrist, Minneapolis VA Health Care System, Mental HealthService Line, Minneapolis, MN, USA2Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota,Minneapolis, MN, USAFull list of author information is available at the end of the articlePrevious presentation: Presented in part at the Society of Biological Psychiatry74th Annual Meeting, Chicago, Illinois, 16–18 May 2019.antidepressant effects, and possible anti-suicidal effects.Single ketamine at subanesthetic dose of 0.5 mg/kg for40 min has demonstrated improvement in mood within afew hours in some patients with treatment-resistantdepression (TRD)1,2. The peak antidepressant effectoccurs at 24-h post-infusion with gradual loss of therapeutic benefit between 5 and 8 days1,3. The strategy ofrepeated ketamine4–7 suggested that several infusionsbeyond a single ketamine increase antidepressantresponse and prolong its durability; however, open-labelstudy designs or the use of saline as placebo limited moreThis is a U.S. government work and not under copyright protection in the U.S.; foreign copyright protection may apply 2020Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproductionin any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate ifchanges were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. Ifmaterial is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtainpermission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Shiroma et al. Translational Psychiatry (2020)10:206definite conclusions. We aimed to overcome these limitations by conducting a two-arm, randomized, activeplacebo-controlled trial. Through a total of six infusionsin 12 days, we compared the efficacy and safety of six IVketamine versus a single IV ketamine among patients withTRD. To balance the number of infusions, subjects in thesingle ketamine arm had five IV midazolam, a shortacting benzodiazepine and anesthetic agent, with fastonset of action, short elimination half-life, and similartime course of dissociative and nonspecific behavioraleffects (e.g., sedation, disorientation) to ketamine8.MethodsStudy design and patientsThe study was conducted at the Minneapolis VeteransAffairs Medical Center between April 2015 and March2019. Subjects were outpatient, aged 18–75 years, metcriteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) by theStructured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV(SCID), and hadlack of response to at least two adequate antidepressanttrials of different pharmacological classes during currentmajor depressive episode (MDE) according to the Antidepressant Treatment History Form (ATHF)9. Systematicevaluation of previous antidepressants was assessed on allavailable information including VA pharmacy, andcommunity-based records. In addition, participants had ascore 32 on the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Clinician Rated (IDS-C30)10 for severity of MDE atscreening. Current antidepressant dosages includingaugmenting agents and/or frequency and duration ofpsychotherapy sessions remained stable for 6 weeksprior to consent and throughout the study.Patient were excluded if they had a lifetime DSM-IVcriteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), mild tomoderate traumatic brain injury, psychosis-related disorder, bipolar disorder, or any Axis I disorder other thanMDD as the primary presenting problem. Patients with ahistory of alcohol or substance use disorder within6 months of screening, imminent risk of suicidal/homicidal ideation and/or behavior with intent, a Mini-MentalState Examination score 27, positive urine toxicology orpregnancy test were also excluded. Medical records andlaboratory tests were reviewed for any unstable medicalillness. Study anesthesiologist were consulted on thosecases with possible medical contraindication toparticipate.Study proceduresRandomization was conducted using permutated blocksof 4 and 1:1 assignment between treatments. The patientsreceived six infusions on a Monday-Wednesday-Fridayschedule over a 12-day period. Patients received fivemidazolam infusions followed by a single ketamine or sixketamine treatments (see Fig. SF1). The fact that the lastPage 2 of 9infusion consisted of ketamine for both arms was keptundisclosed to subjects and raters of antidepressant outcomes at 24 h. Each infusion of ketamine at 0.5 mg/kg ormidazolam at 0.045 mg/kg lasted 40 min. The selection ofketamine and midazolam doses was based on previousRCTs1,11. The dose of ketamine and midazolam werecalculated by ideal body weight based on sex, age, height,and body frame in the Metropolitan Life Insurance tables.Group assignments for each participant was concealed insequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes withdrug identity by the research pharmacist; investigators,raters, and patients were masked to treatment assignment.Patients arrived at the infusion unit after fasting for atleast 8 h. An indwelling catheter was placed in peripheralvein of non-dominant arm for medication administration;monitor of pulse, blood pressure, digital pulse oximetry,and respiratory rate was recorded every 10 min for 1 hbeginning 10 min before infusion. Trained raters administered pre-infusion rating scales and repeated themagain during a 2-h post-infusion monitoring period. Astudy physician was present throughout the infusion andstudy anesthesiologist (J.W.) was reached, if necessary.Medications such as labetalol, hydralazine, ondansetron,and flumenazil as well as a crash cart were available tomanage adverse side effects. Guidelines established forclinically significant changes in vital signs and mentalstatus during the ketamine infusions were as follows:systolic blood pressure 161 or 89, diastolic BP 110 or 40; heart rate 40 or 130 beats/min; respiratory rate 10 or 30 per minute; pulse oximetry 90%; severehallucinations, confusion, delusions, irrational behavior,or agitation. Before leaving the infusion unit, subjectsdemonstrated that all clinically significant side effectswere resolved by a score 9 in the modified Aldretescoring system12. Written instructions about potentialside effects of sedatives and several measures to improverecovery at home (e.g., proper hydration and rest; abstainfrom alcohol) were provided at discharge to patient andcompanion adult.OutcomesThe study assessments were performed at days 0, 1, 3, 5,8, 10, and 12 to assess the safety and efficacy of ketaminecompared to active placebo during infusion phase. Posttreatment assessments were measured at weekly intervalsfor the first 4 weeks, at 2-week intervals for the next8 weeks, and at 4-week intervals for the remaining12 weeks. The primary outcome was change in depressionseverity measured by the clinician-administered Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score(MADRS)13 at 24 h (T 24) after the last infusion. Raterswere trained in MADRS prior to and during study with alevel of interrater reliability of 0.92. Secondary outcomesincluded change in MADRS score over time, rates of

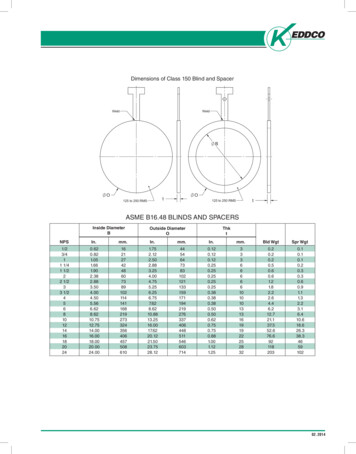

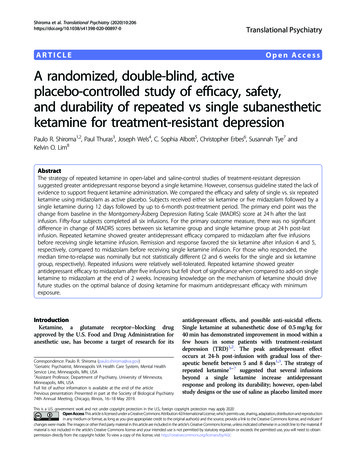

Shiroma et al. Translational Psychiatry (2020)10:206response ( 50% MADRS reduction in the baseline score),rates of remission (MADRS 10), rates of response andremission over time, and durability of response for up to6 months. Other secondary outcomes included clinicalglobal impression (CGI) severity and improvement measures14, self-reported numeric rating scale (NRS) forpain15, Beck anxiety inventory (BAI)16, and credibility andexpectancy questionnaire (CEQ)17 for clinical treatment.Cognitive performance (CogState)18, and functional neuroimaging on a sub-sample of patients will be reportedseparately.General side effects were measured by the patient ratedinventory of side effects (PRISE). Psychotogenic effectswere measured with the four-item positive symptomsubscale of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS )19consisting of suspiciousness, hallucinations, unusualthought content, and conceptual disorganization; dissociative effects and manic symptoms were measured withthe Clinician-Administered Dissociative States Scale(CADSS)20 and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)21,respectively. Additionally, The Columbia-Suicide SeverityRating Scale (C-SSRS) Screening Version–Since LastVisit22 was rated during and after infusion phase for safetypurposes.Statistical analysisThe power analysis was performed for MADRS scoreunder the following assumptions: (1) analyses of covariance with the main effects of treatment (a single versussix infusions) and time (0 and Day 13), and the treatmentby time interaction; (2) compound symmetric covariancematrix, and (3) 5% significance level. Our previous openlabel study of six repeated ketamine in TRD patients4showed a difference of 23 points in MADRS score frombaseline to 24 h after the last infusion (mean MADRSscore 29.9, SD 2.3 to mean MADRS score 7.0, SD 2.3). Based on these results, we estimated that a samplesize of 21 patients per group was powered to detect a 10point difference in change of MADRS score between thesingle versus repeated ketamine group. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to test for differences betweengroups in change from baseline to T 24 after the lastinfusion and baseline and T 24 after the fifth infusion.Multi-level models were used to compare groups onchange across all MADRS measures. All tests were twosided with significance at p 0.05.Page 3 of 9Health Care System Institutional Review Board (protocolnumber 4533-B).ResultsStudy participantsOne-hundred seventy-eight individuals were prescreened for eligibility through consultation with studyphysicians. Of these, 62 signed consent forms andunderwent formal in-person screening (see the CONSORT diagram in Fig. SF2). There were four participantswho failed screening; 58 subjects were randomized totreatment with four patients dropping prior to baselinedata collection. All 54 subjects with baseline assessment,initiated study interventions and completed primaryoutcome end point. Five midazolam plus single ketaminegroup was composed by 29 subjects; a total of 25 subjectswere in the six-ketamine group.Participants’ baseline characteristics are summarized inTable 1. There was no significant difference betweengroups for demographic and clinical characteristics. Thesample was mostly composed by middle aged, unemployed or retired, married, white males with a history ofmood disorder among first-degree relatives. Patients hadalso a chronic history of depression that included at leastone past psychiatric hospitalization with almost half of thepatients reporting a previous suicidal attempt. Overall,patients had a current MDE with severe symptoms thatfailed to more than 02 adequate antidepressant trials andaugmenting agents.Primary outcomeThere was no significant difference between single(MADRS mean change 21.0, 95% CI 17.2–24.8) versus six ketamine treatments (MADRS mean change 17.2, 95% CI 13.2–21.2) at T 24 after the end of treatment (six infusions) (F1,52 2.41, P 0.13, ηp2 0.044)(Fig. 1). There was a significant change in MADRS scoreby groups over time when including all MADRS measures(F11,541.11 2.63, P 0.003). The mean MADRS scoreamong subjects receiving ketamine was significantly lowerby 8.07 (95% CI, 1.67–14.46) prior to infusion 5 (F1,95.7 6.28, P 0.014), by 8.29 (95% CI, 1.87–14.70) at T 24after infusion 5 (F1,96.7 6.58, P 0.012) and by 6.40 (95%CI, 0.01–12.79) prior to infusion 6 (F1,95.7 3.94, P 0.050) compared to subjects receiving midazolam.Ethics approvalSecondary outcomesResponse and remission ratesThe authors assert that all procedures contributing tothis work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on humanexperimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving humansubjects/patients were approved by Minneapolis VAThe response rates were not significantly differentbetween groups at the end of six infusions (X21df 0.73,P 0.39) (Fig. 2a). There was also no significant differencein remission rates at T 24 after the last infusion betweenrepeated midazolam plus single ketamine versus repeatedketamine (X21df 0.56, P 0.46) (Fig. 2b). Throughout the

Shiroma et al. Translational Psychiatry (2020)10:206infusions phase, there was a significant difference inremission rates at T 24 after infusion 4 (six ketamine 54.2% versus midazolam 17.9%; X21df 7.53, P 0.006)and in response rates at T 24 after infusion 5 (six ketamine 76% versus midazolam 39.3%; X21df 7.25, P 0.007).Page 4 of 9Table 1 Baseline demographic and clinical characteristicsof patients with treatment-resistant depression treatedwith five midazolam plus a single ketamine versus sixketamine infusions.CharacteristicsOther secondary outcomesThere was non-significant difference in anxiety asmeasured by BAI score change over times between groupsat the end of infusion 5 (F4,182.28 1.74, P 0.14) andinfusion 6 (F5,234.50 1.53, P 0.18). Self-rated pain alsodid not show significant difference between groups overinfusion time points (F5,238.34 1.29, P 0.27). There wasa significant improvement in CGI for subjects in bothgroups, midazolam plus single ketamine (baseline mean 5.14, 95% CI 4.75–5.53 to post-infusion mean 2.63,95% CI 2.14–3.12) (t (56) 8.01, p 0.001) and sixketamine (baseline mean 5.32, 95% CI 4.90–5.74 topost-infusion mean 2.01, 95% CI 1.55–2.48) (t (48) 10.63, p 0.001) without significant difference betweengroups (F1,54.83 3.59, P 0.06) at T 24 after the end oftreatment. There was no significant difference betweengroups in credibility (F1,52 0.19, P 0.66) and expectancy (F1,52 0.03, P 0.86) of treatment as measured byCEQ scores. There was no significant difference in themean change of MADRS score from baseline to T 24 afterthe last infusion between subjects taking benzodiazepines(N 11, mean change MADRS score 22.9, SD 9.5) ornot taking benzodiazepines (N 13, mean change inMADRS score 23.2, SD 6.5) (F1,22 0.01, P 0.94) inthe six ketamine group.Durability of responseMADRS scores at weekly for 4 weeks, biweekly for8 weeks, and monthly for 3 months were used to determine time-to-relapse (MADRS 50% from baseline)among patients who achieved response after the lastinfusion (N 20 for midazolam plus single ketamine andN 19 for six ketamine). The Kaplan–Meier estimates ofthe 6-month relapse rates after response (Fig. 3) was 75%(95% CI 54.2–95.8%) and 68.4% (95% CI 45.4–91.4%)for midazolam plus single ketamine and six ketaminegroup, respectively. The long-rank test revealed a nonstatistically significant difference between relapse ratesover time (X21df 1.61; P 0.21). The median time-torelapse was 2 weeks for the midazolam plus single ketamine group, and 6 weeks for the six-ketamine group (95%CI for the hazard ratio 0.3 to 1.4; P 0.27).Adverse eventsDuring infusion phase, the most common side effectsfor ketamine were general malaise (28.0%), decreasedenergy (28.0%), increased in blood pressure (24.0%),SixketamineFivemidazolamplus singleketamineOverall sample(N 25)(N 29)(N 54)Mean SDMean SDMeanSDAge (years)54.413.8 51.212.5 52.713.1Level of education (years)Age of first MDE (years)14.525.62.1 14.711.6 25.02.0 14.610.1 25.32.010.4Number of lifetime MDEDuration of current MDE (weeks)5.378.32.6 6.139.6 84.93.8 5.735.3 81.93.337.1Number of adequate antidepressanttrials during current MDELifetime number ofantidepressant 87.338.436.83.9MaleN22%N88.0 24%N82.8 46%85.2RaceWhite2184.0 2586.2 4685.23112.0 14.0 33.4 410.3 47.47.4MarriedUnemployed/retired171668.0 1264.0 1941.4 2965.5 3553.764.8Melancholic depression832.0 620.7 1425.9Black/African AmericanOtherComorbid conditionsAnxiety spectrum6.1417.4 520.0 916.7DysthymiaSub-syndromal PTSD6624.0 524.0 517.2 1117.2 1120.420.4Personality disorderChronic pain41016.0 240.0 96.9 631.0 1911.135.2Sleep disorderTobacco disorder142256.0 1488.0 2348.3 2879.3 5151.994.4Severe MDEHistory of AUD/SUD151060.0 1140.0 837.9 2627.6 1848.133.31976.0 1862.1 3768.63912.0 736.0 1124.1 1037.9 2018.537.0Previous suicidal attemptPrevious psychiatric hospitalization121748.0 1458.6 1848.3 2672.0 3548.164.8Past ECT treatmentConcurrent use of416.0 724.1 1120.4Augmenting agentsBenzodiazepines181272.0 2148.0 1172.4 3937.9 2372.242.6Psychotherapy936.0 1241.4 2138.9Family history ofMood disorderOther psychiatric disorderAUD/SUDheadaches (24.0%), fatigue (24.0%), nausea/vomiting(20.0%), anxiety (20.0%), and poor concentration (20.0%).Within the same period, the most common adverse eventsfor midazolam plus single ketamine were anxiety (24.1%),decreased energy (17.2%), increased in blood pressure(17.2%), fatigue (13.8%), and headaches (13.8%).

Shiroma et al. Translational Psychiatry (2020)10:206Page 5 of 9*A80352520*15*70Rate of Response (%)30¶6050403020100Infusion 11050Infusion 2Infusion 3Infusion 4Infusion 5Infusion 6Treatment*P 0.007Six KetamineMidazolam plus Single KetamineT-60 T 24hrs T-60 T 24hrs T-60 T 24hrs T-60 T 24hrs T-60 T 24hrs T-60 T 24hrsInfusion 1*P 0.01; ¶P 0.05Infusion 2Infusion 3Infusion 4Infusion 5Infusion 6B*60TreatmentMidazolam plus Single KetamineSix KetamineFig. 1 Mean Change in Severity of Depression between SixKetamine versus Midazolam plus Single Ketamine Treatmentwithin a 12-day Period. Severity of depression scores measured bythe Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) over12 days between six ketamine and five midazolam plus singleketamine (last infusion) treatment groups in a randomized controlledtrial in treatment-resistant major depression. Figure depicts meanMADRS scores in patients with treatment-resistant depression beforeand after 24 h of each ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) or single ketamine(0.5 mg/kg) preceded by five midazolam (0.045 mg/kg) infusion. *indicates significant difference in MADRS score between treatmentcondition (p 0.01) before and at 24 h after infusion 5. ¶Indicatessignificant difference in MADRS score between treatment conditions(p 0.05) before infusion 6.Vital signsThere were 25 and 17 cases of mild and moderateadverse events during infusion phase, respectively. Moderate side effects were related to transient hypertensiveepisode (systolic 161 or diastolic 110 per protocol) thatrequire at least one dose of antihypertensive medicationsuch as labetalol or hydralazine as recommended by studyanesthesiologist. Moderate adverse events also includednausea that required IV medication (e.g., ondansetron).Mild cases included increased blood pressure or nauseathat subsided without medications, and IV site bruisingbut not pain. During infusions 1–5, there was a significantly higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure atT 40m (systolic mean difference 25.6, 95% CI:16.4–34.9; diastolic mean difference 12.9, 95% CI:7.2–18.8) and diastolic blood pressure at T 100m (meandifference 12.9, 95% CI: 3.6–22.2) for the ketaminegroup compared to midazolam. There was no significantdifference in heart rate between groups at any time pointduring infusions (data not shown).Dissociative, psychomimetic, and maniaDuring infusions 1–5, there was a significantly greaterdissociation measured by CADSS score at T 40m (meandifference 12.8, 95% CI: 10.1–15.6) for the ketaminegroup (mean 15.3 95% CI: 13.3) compared toRate of remission (%)Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)Score4050403020100Infusion 1Infusion 2Infusion 3Infusion 4Infusion 5Infusion 6Treatment*P 0.006Six KetamineMidazolam plus Single KetamineFig. 2 Antidepressant Response and Remission Rates betweenSix Ketamine versus Midazolam plus Single Ketamine Treatmentwithin a 12-day Period. a Response rates over 12 days between sixketamine and five midazolam plus single ketamine (last infusion)treatment groups in a randomized controlled trial among subjectswith treatment-resistant major depression. Response is defined as 50% decrease from baseline score measured by the MontgomeryÅsberg Depression Rating Scale. Figure depicts response in patientswith treatment-resistant depression measured at 24h after eachketamine (0.5 mg/kg) or single ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) preceded by fivemidazolam (0.045 mg/kg) infusion. * indicates significant difference inresponse between treatment conditions (p 0.007) at 24h afterinfusion 5 (Fig. 2b). Remission rates over 12 days between six ketamineand five midazolam plus single ketamine (last infusion) treatmentgroups in a randomized controlled trial among subjects withtreatment-resistant major depression. Remission is defined as score 10 in the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale. Figure depictsremission in patients with treatment-resistant depression measured at24 h after each ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) or single ketamine (0.5 mg/kg)preceded by five midazolam (0.04 5mg/kg) infusion. * indicatessignificant difference in remission between treatment conditions (p 0.006) at 24 h after infusion 4.midazolam (mean 2.5 95% CI: 0.6–4.4) (see Fig. SF3).All patients receiving ketamine had complete resolutionof dissociative side effects within the 2-h monitoringperiod. Participants’ dissociative side effects (change inCADSS score a T 40m) were non-significantly correlatedwith antidepressant response (change in MADRS score) atT 24h post-infusion for midazolam (Pearson’s r –0.03,p 0.89) or ketamine (Pearson’s r 0.04, p 0.86).Comparison of change in CADSS scores in the ketaminegroup at T 40m (peak of side effects) revealed non-

Shiroma et al. Translational Psychiatry (2020)10:206Page 6 of 9(X21df 9.12; P 0.002). Raters, who were different during infusions days from those rating antidepressant outcomes at 24 h., incorrectly guessed 20.8% of midazolamcases and 7.1% of repeated ketamine cases prior to the lastinfusion (X21df 1.25; P 0.26). After the last infusion,6.9 and 26% raters were incorrect about treatmentassignment among midazolam plus single ketamine andrepeated ketamine cases, respectively (X21df 3.62; P 0.06).DiscussionFig. 3 Time-to-relapse between responders to single vs sixketamine infusions in treatment-resistant depression. Figuredepicts Kaplan–Meier analysis of responders for up 6 months offollow-up. Relapse was defined as 50% improvement inMontgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score at that visitcompared with baseline.significant change in dissociative side effects with repeated infusions (F5,220.28 1.83, P 0.11). There was notsignificant change within or between groups regardingpsychotic (BPRS ) (see Fig. SF4) or elevated moodsymptoms (YMRS-item 1) at any time point throughoutinfusions.Serious adverse eventsThere were two cases deemed as a serious adverse eventthat required IRB report (see Table ST1): one patient(assigned to midazolam) complained of headaches triggered by loud noises and bright lights after post-infusionMRI as part of study protocol; another patient (assignedto ketamine) reported mild headaches during secondinfusion, which increased during follow-up phase. Headaches in both cases were considered unrelated to studydrugs and eventually subsided. Through interviews withsubjects, no suicidal attempts nor drug-seeking behaviorwere elicited throughout the study.BlindingSubjects were asked prior to and at the end of the lastinfusions (T 160) about treatment allocation. Prior to thelast infusion (midazolam versus ketamine), 6.3% amongmidazolam cases and 56.3% among ketamine cases wereerroneous about what treatment they were assigned to(X21df 9.30; P 0.002). At the end of the last infusion(midazolam plus single ketamine versus six ketamine),10.7% among midazolam cases and 50.0% among ketamine cases guessed incorrectly about assigned treatmentThis single center study of Veterans with moderate-tosevere, recurrent, TRD showed that for the primary outcome measure, there was no significant difference inchange of MADRS scores between groups at 24 h postlast infusion at the end of 12 days of treatment. Repeatedketamine showed greater antidepressant efficacy compared to midazolam after five infusions before receivingsingle ketamine as the last infusion. The rate of remissionand response was greater among subjects in the sixketamine group after infusion 4 and 5, respectively. Forthose subjects who responded to either assigned treatment, six ketamine tripled the median time-to-relapseover a 6-month period as compared to those in themidazolam plus single ketamine group; however, it fellshort of statistically significant difference. Transient psychoactive and hemodynamic effects during ketamineinfusion were consistent with those in previous reports7,6and did not increase when repeated treatments were givenin a short-term fashion.The prospect of whether repeated dosing of ketamineoffer safe and superior antidepressant outcomes is a critical question as studies have shown that frequent use ofketamine could lead to cognitive impairments23, dissociation, and poor impulse control24. Medical, legal, andeven ethical concerns of using repeated ketamine to treatpsychiatric conditions have been raised25. Despite thesmall sample in this study, this is the largest randomizedstudy that compare repeated ketamine versus an activeplacebo in TRD. Previously, Singh and colleagues26showed that both twice-weekly and thrice-weeklyadministration of ketamine over 15 days of treatmenthad greater antidepressant efficacy versus saline (leastsquare mean change in MADRS score of 16.0 and 16.4points, respectively). An open-label study of thrice ketamine weekly for 2 weeks among unipolar and bipolardepressed Chinese patients7 showed an overall reductionof 15.5 and 18.7 points in MADRS score at 24 h. afterketamine infusion 5 and 6, respectively. A more recentlystudy among patients with TRD who responded and thenrelapsed after a cross-over single ketamine (versus midazolam)6 showed a reduction of 12 points in MADRSscore after completing an open-label treatment of thrice aweek for 2 weeks.

Shiroma et al. Translational Psychiatry (2020)10:206From these previous studies, our findings support theidea that repeated ketamine further reduce the severity ofdepression in TRD. However, the antidepressantimprovement through six ketamine treatments was notsignificantly different when compared to a single ketamine. Previous reports on repeated ketamine consistentlyfound that the largest improvement ( 50%) in TRDoccurred after the first infusion26,7,6,4,27,28. It is likely thenthat the relatively small sample in our study was insufficient to capture any significant difference between antidepressant gain beyond the first infusion in the repeatedketamine group versus that in the single ketamine. On theother hand, subjects in the repeated ketamine groupachieved a mean group treatment difference of 4.0against repeated midazolam plus single ketamine at 24 hafter the last infusion. A 4-point difference on theMADRS has been suggested as a stringent criterion forjudging whether an effect size is clinically relevant29 withmore recent reports suggesting a minimal clinicallyimportant difference threshold of 2 points in MADRS30.Moreover, Popova and colleagues31 on

compared to active placebo during infusion phase. Post-treatment assessments were measured at weekly intervals for the first 4 weeks, at 2-week intervals for the next 8 weeks, and at 4-week intervals for the remaining 12 weeks. The primary outcome was change in depression severity measured by the clinician-administered Mon-