Transcription

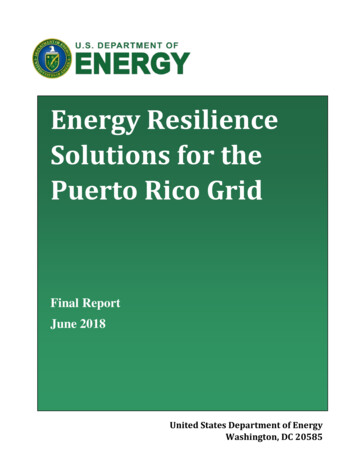

Energy ResilienceSolutions for thePuerto Rico GridFinal ReportJune 2018United States Department of EnergyWashington, DC 20585

List of AcronymsAct EMANERCNESCNISTAct for the Transformation and Energy Relief of Puerto Rico, 2014Advanced Distribution Management SystemsAutomated Information SharingAdvanced Metering InfrastructureArgonne National LaboratoryAmerican Recovery and Reinvestment ActBase Flood ElevationCustomer Average Interruption Duration IndexCombined Heat and PowerContributions in Lieu of TaxesCritical Infrastructure ProtectionCongressional Research ServiceDistributed Energy ResourcesDistributed Energy Resource Management SystemUnited States Department of Homeland SecurityUnited States Department of DefenseUnited States Department of EnergyDebt Service Coverage RatioEmergency Management Assistance CompactEmergency Support Function 12 – EnergyFederal Emergency Management AgencyFederal Energy Management ProgramFlood Insurance Rate MapFinancial Oversight and Management BoardGross Domestic ProductGrid Modernization Laboratory ConsortiumGeneral Services AdministrationIncident Command SystemInstitute for Island Energy SustainabilityIncident Management TeamIntegrated Resource PlanInformation Sharing and Analysis CenterInformation TechnologyLawrence Berkeley National LaboratoryLevelized Cost of ElectricityLong Island Power AuthorityLiquefied Natural GasMercury and Air Toxins StandardMunicipal Solid WasteNational Association of Regulatory Utility CommissionersNational Association of State Energy OfficialsNational Electrical Manufacturers AssociationNorth American Electric Reliability CorporationNational Electrical Safety CodeNational Institute of Standards and Technology2

tional Oceanic and Atmospheric AdministrationNational Renewable Energy LaboratoryNew York Power AuthorityOak Ridge National LaboratoryOperational TechnologyPower Marketing AdministrationPuerto Rico Energy CommissionPuerto Rico Electric Power AuthorityPuerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability ActPublic Utility CommissionPhotovoltaicRocky Mountain InstituteRenewable Portfolio StandardRecovery Support FunctionRural Utilities ServiceSystem Average Interruption Duration IndexSystem Average Interruption Frequency IndexSandia National LaboratoryTransmission and DistributionUniversity of Puerto RicoUnited States Army Corps of EngineersUnited States Department of AgricultureUnited States Geological SurveyUnited States Virgin IslandIrrigation & Electrical Workers UnionWaste-to-Energy3

Table of ContentsExecutive Summary . 5A. Introduction . 9A1. Purpose . 9A2. Existing Long-Term Recovery Visions and Principles. 10A3. Recommendations for Immediate Action . 10B. The Pre-Storm Condition of the Electricity System. 12B1. Portfolio Considerations . 12B2. System Performance . 12B2A. Reducing Political Influences Over Infrastructure Decisions . 13B3. Assumptions on Demand . 14B3A. Energy Efficiency and Demand Response . 14B3B. Infrastructure Interdependencies . 15C. Recommendations by Subject Matter . 18C1. Transmission and Distribution . 18C1A. Context for Transmission Recommendations . 19C1B. Context for Distribution Recommendations . 21C1C. Substations . 22C1D. Selective Segmentation . 22C2. Generation . 24C2A. Context for Generation Recommendations . 25C2B. Increases in Renewable Energy . 27C3. Microgrids . 29C3A. Context for Microgrid Recommendations. 30C4. System Operations, Management, and Planning. 33C4A. Context for Planning Improvement Recommendations . 34C4B. Human Resources and Training . 40C4C. Standards, Regulatory and Legislative Actions to Enhance Long-term Recovery . 40D. Conclusion . 42Appendix A: Scenarios . 44Appendix B: Consolidated Recommendations from Long-term Plans. 47Appendix C: DOE Recommended Actions . 54Appendix D: Microgrid Tools . 584

Executive SummaryThe eye of HurricaneMaria careened justsouth of the UnitedStates Virgin Island ofSt. Croix in the earlyhours of September 20,2017, and landed inYabucoa, Puerto Rico,shortly thereafter.Arriving with maximumwinds just below thethreshold of category 5intensity, the wind, rain,and storm surge duringMaria’s eight hours overPuerto Rico combined todisrupt nearly all water,electricity, andtelecommunicationsservices.Figure 1: Hurricane Maria Making Landfall Over Puerto RicoSeptember 20, 2017 (Credit: NOAA; CIRA)Hurricane Maria was the second strongest storm on record to hit Puerto Rico. 1 As of 8:00 PMEDT on September 20, the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) reported near 100%of total customers in Puerto Rico without power, with the exception of facilities running ongenerators. The outage threatened the health, safety, and economic wellbeing of the nearly 3.5million U.S. citizens who inhabit the territory and further stressed the regional economy. Arecent report by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)estimated that the monetary value of the total damage caused by Hurricane Maria in Puerto Ricoexceeded the next most costly hurricane to hit the Commonwealth by an order of magnitude. 211928 Okeechobee hurricane, also known as the San Felipe Segundo hurricane, was the strongest hurricane onrecord to hit Puerto Rico.2NOAA, National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Maria (Apr. 5, 2018)https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL152017 Maria.pdf. This report estimates that the total damage to theCommonwealth ranges from 65-115 billion.5

Figure 2: Sampling of Historic Hurricanes to Hit Puerto Rico (Credit: Sheila Murphy, USGS)While this scale of restoration and recovery would challenge any community, Puerto Rico hasalready faced economic and workforce issues which exacerbated the difficulty of restorationefforts and dimmed the prospects of a quick recovery. Out-migration of skilled power engineersand line workers, driven by a variety of factors, has accelerated in pace from 2010 through theclose of 2017, with more Puerto Ricans now living in the continental United States than in theCommonwealth. The loss of human capital caused by this out-migration will further challengePuerto Rico’s ability to re-start its economy.Despite such adversity, the people of Puerto Rico have shown tremendous strength and resilienceas they restore and rebuild their homes and communities. Leveraging the electricity grid to spureconomic growth in Puerto Rico’s various communities and economic sectors, including healthcare, manufacturing, tourism, and agriculture, is essential to revitalization of the island.Essential services from energy-enabled critical infrastructure including water, waste water,waste, telecommunications, and transportation must be consistently and reliably operational tosupport safety and health. Additionally, manufacturing and retail operations must be open andemployable to support economic wellbeing. A strong recovery and revitalization is importantnot only to the region, but also to the United States as a whole.Maintaining and enhancing the resilience of the electric grid at fair and reasonable costs canprovide service and value to Puerto Rican communities. Yet, no single investment in energy6

infrastructure at one point in time will achieve resilience. The energy infrastructure of PuertoRico must be designed, built, managed, and maintained in such a way to withstandenvironmental and man-made disasters, ameliorate disruptions when they inevitably occur,recover quickly, and incorporate lessons learned into post-event planning and operations. This isa continual process of improvement, one involving a reassessment and adaptation of solutionsand technologies to address changing needs.In support of those goals, this report contains resilience recommendations for the Government ofPuerto Rico to consider for incorporation into its recovery plans—including the plan specified bySection 21210 of P.L. 115-123 (2018), and to provide useful insights for the disbursement of anyfederal appropriations intended to rebuild or improve the energy infrastructure in theCommonwealth of Puerto Rico. 3 Given the breadth of interdependencies across sectors,assessment of potential alignment and sequencing of funding across different agency programsthat support various sector infrastructures would be beneficial. The report also notes whereadditional analysis is needed to more precisely articulate resilience-related, investment-gradesuggestions regarding the design and specification of the electricity system in Puerto Rico.Although additional analysis is necessary to further specify some of this report’srecommendations that support resilience, recommendations that can be acted on today toimprove the performance of the system are as follows:1. The Governor and PREPA should immediately ensure that updated, effective mutual aidagreements and Incident Command System are primed to quickly provide support during thenext event.2. The Puerto Rico Energy Commission (PREC) should coordinate a joint study with the PuertoRico Telecommunications Board to determine and enforce safe loading requirements ofdistribution poles carrying both electric and telecommunications infrastructure.3. Electricity transmission towers installed specifically for temporary emergency restorationshould be considered for prioritized replacement, potentially by monopoles. Many roundmonopole structures withstood the storm effectively.4. The PREC, in coordination with PREPA, should implement microgrid regulations in linewith accepted industry standards and practices; and establish effective, efficient, andreasonable interconnection requirements and wheeling regulations. These regulations willallow customers to design their systems in a manner that support the reliability and resilienceof the broader electricity grid.5. The Puerto Rican State Office of Energy Policy or its successor, in coordination with otherappropriate Commonwealth agencies and instrumentalities, should immediately commencedrafting of an updated Energy Assurance Plan. This plan should provide for, among others,the use of the Incident Command System including the immediate establishment of astanding Incident Management Team.3For example, in early April the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development announced the largest singleamount of available Disaster Recovery Community Development Block Grant funds, including over 20 billion forPuerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands,https://www.hud.gov/press/press releases media advisories/HUD No 18 028.7

Several recommendations require further analysis to fortify the recommendations; the analysisshould be conducted, to the extent practical, with the support and engagement of PREPA and theGovernment of Puerto Rico, includes the following:1. Power flow – assesses power system operations, including generator dynamics andprotective relay coordination [used to identify power system needs, evaluate technologyoptions, and help prioritize resilience investments, e.g., transmission enhancements]2. Production cost and capacity expansion – informs economic dispatch strategies and longterm planning [used to understand how resource investments, system costs, and load areimpacted by key policy and technology sensitivities]3. Microgrids, energy storage, and system segmentation – identifies where clusters ofgeneration and load provide maximum community benefit [used to identify prepositioning ofemergency generation, local hardening of infrastructure, and adjustment of emergencyprocedures]4. Infrastructure interdependencies – characterizes reciprocal relationships within the energysector (e.g., electricity-petroleum, electricity-LNG), as well as cross-sector infrastructure liketelecommunications and/or water [used to investigate supply disruption impacts and identifymitigation approaches]A summary of the DOE’s specific recommendations can be found in Appendix C.8

A. IntroductionA1. PurposeThis report contains recommendations for the Government of Puerto Rico to consider forincorporation into its recovery plans, including the plan that Congress specified in Section 21210of P.L. 115-123 (2018). 4 The recommendations reflect principles of resilience, 5 and areintended to inform investments that use federal appropriations in the energy infrastructure in theCommonwealth of Puerto Rico (hereafter “Commonwealth” or “Puerto Rico”). 6These recommendations address some near-term actions and identify where further analysis isneeded to make more technically-informed investment decisions. The recommendations shouldhighlight where coordination across agencies and sectors may improve the resilience ofinfrastructure in Puerto Rico. While each of the recommendations, if implemented, wouldimprove the resilience, a resilient energy system is not achieved through a single investment orseries of investments at a given time.Rather, resilience results from an on-going focus on identifying and undertaking soundinvestments, operating and maintenance procedures, and planning practices. Each of thedecisions in this iterative process should aim to enhance the ability of the system to withstandlikely stresses, ameliorate disruptions when they inevitably occur, recover quickly, andincorporate lessons learned into post-event planning and operations.This report is NOT a grid modernization roadmap or implementation strategy for Puerto Rico. Itrecognizes that capital investment alone will likely be insufficient to achieve Puerto Rico’s goalof an electric sector that is technically reliable, resilient, and affordable; after all, mostinvestments will have longer-term obligations associated with operations and maintenance costs.Thus, success ultimately depends on the leadership and commitment of the Government ofPuerto Rico and entities such as PREC and PREPA to carefully identify Puerto Rico’s electricityneeds, assess the options, and make their own determination of a strategy that meets long termgoals and instills confidence for existing and new industries to invest on the island.4This section reads, in relevant part: “Not later than 180 days after the date of enactment of this subdivision and incoordination with the Administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, with support and contributionsfrom the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of Energy, and other Federal agencies having responsibilitiesdefined under the National Disaster Recovery Framework, the Governor of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico shallsubmit to Congress a report describing the Commonwealth’s 12- and 24-month economic and disaster recovery plan. . .”.5See, e.g., National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2017. Enhancing the Resilience of theNation's Electricity System. Washington, DC: The National Academies ewsitem.aspx?RecordID 24836.6Given the differences between the Commonwealth and the United States Virgin Islands (USVI), the USVI are notaddressed in this report. However, DOE staff and experts at the National Labs are working with their USVIcounterparts to improve resilience and reliability of the energy system for the benefit of the American citizens there.9

A2. Existing Long-Term Recovery Visions and PrinciplesOn December 13, 2017, DOE convened experts from the community of public and privateenergy stakeholders who had expressed interest in supporting the long-term recovery of PuertoRico (hereafter “December meeting”). The event stimulated continued dialogue on forming acohesive set of recommendations, based on the expert opinion of the varied stakeholders,ensuring a strong technical rational for Puerto Rico’s energy investment decisions.By the time of the December meeting, several participants had already issued their own vision,roadmap, or recommendations for the restoration, recovery, and further modernization of thePuerto Rican electricity grid. These publications varied greatly in their depth, detail, and scope.A summary of these publications can be found in Appendix B.All plans appeared to agree that modernization would serve recovery objectives, and all agreedon the need to diversify and harden infrastructure against possible future disasters. Manyparticipants expressed the desire for a single vision for the future of Puerto Rico’s electricitysector. The Commonwealth itself must establish that vision and ensure the appropriategovernance mechanisms are available to accurately reflect the needs of customers in that vision,as well as guarantee accountability within the management of the energy sector to honor thatvision.A3. Recommendations for Immediate ActionThis report considered and integrated plans and materials from multiple resources. Many of therecommendations in this report require further analysis to refine into investment-grade decisions.However, while this analysis continues, the following recommendations can be acted upon todayto improve the performance of the electricity system:1. The Governor and PREPA should immediately ensure that updated, effective mutual aidagreements and Incident Command System are primed to quickly provide support during thenext event.2. The Puerto Rico Energy Commission (PREC) should coordinate a joint study with the PuertoRico Telecommunications Board to determine and enforce safe loading requirements ofdistribution poles carrying both electric and telecommunications infrastructure.3. Electricity transmission towers installed specifically for temporary emergency restorationshould be considered for prioritized replacement, potentially by monopoles. Many roundmonopole structures rode withstood the storm effectively.4. The PREC, in coordination with PREPA, should implement microgrid regulations in linewith accepted industry standards and practices; and establish effective, efficient, andreasonable interconnection requirements and wheeling regulations. These regulations willallow customers to design their systems in a manner that support the reliability and resilienceof the broader electricity grid.5. The Puerto Rican State Office of Energy Policy Office or its successor, in coordination withother appropriate Commonwealth agencies and instrumentalities, should immediatelycommence drafting of an updated Energy Assurance Plan. This plan should provide for,among others, the use of the Incident Command System including the immediateestablishment of a standing Incident Management Team. Besides preparing for the nexthurricane season, moving immediately will leverage the local presence of utility industry10

response professionals working with PREPA and federal staff in the Joint Field Office.Finally, the Southern States Energy Board may be able to facilitate peer-to-peer informationsharing and lessons learned from other states and utilities.Figure 3: Expectations for the Grid (Source: LBNL) 77https://emp.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/feur 9 webinar value-added services 20171106 fin.pdf.11

B. The Pre-Storm Condition of the Electricity SystemB1. Portfolio ConsiderationsAs became clear in the December meeting and subsequent discussions, four common goals recurin discussions of the electricity system in Puerto Rico: 1) a reliable electricity supply, 2) withconsistent power quality, 3) at foreseeable and manageable cost, 4) that maximizes use of localresources. These goals must be met under the constraints of underinvestment in an already aginginfrastructure, unimplemented legal requirements regarding improvements to electricity systemgovernance and investment decisions, and declining load.B2. System PerformanceThis section will rely primarily on two PREC Orders and quote from them often. The first, FinalResolution and Order PREPA Rate Review, was issued on January 10, 2017 in Docket CEPRAR-2015-0001 (“Rate Review Order”). 8 While this document contains a wealth of informationon PREPA’s system and operations, other documents in this docket, such as the Expert Reportsdated Nov. 23, 2016, are also full of information on these issues and comparisons to standardpractice in the states. The PREC summarized its findings of fact, conclusions of law, andCommission Directives over pages 162-184. There are 120 Commission Directives regardingimprovements of PREPA’s system, operations, and legal compliance.The second document, the Final Resolution and Order on the First Integrated Resource Plan forPREPA (“IRP Order”) in docket CEPR-AR-2015-0002 is dated Sept. 26, 2016, shortly after thepassage of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA).In subject matter, it is less wide-ranging than the Rate Review Order, with its findings of fact andconclusions of law on pages 93-101. It details the changes that will be made to PREPA’s system,with a schedule and competitive bidding requirements for many items. “PREPA’s officials and consultants describe an inefficient bureaucracy with highabsenteeism, overly staffed with non-value-added administrative personnel. Procedures forbudgeting and spending do not provide sufficient information on individual project plans andcompletion. On major capital projects, PREPA was often unable to provide basicexplanations, work-plans, or other due diligence documentation.” Rate Review Order, p. 3“PREPA’s own witnesses describe PREPA’s physical situation to be an ‘ailing grid,’‘degraded infrastructure,’ and a ‘deteriorated’ transmission system.” Rate Review Order, p.16On another metric, PREPA’s forced outage factor of plants averaged 6.87% over 2010-15, butended that period at nearly 27%. Some units were completely out of service for extended periodsof time, while the best performing plant was fired by natural gas supplied by Gas Natural Fenosa,majority owner of EcoEléctrica, achieving an availability rate of 97% and average capacity8http://energia.pr.gov/numero orden/cepr-ap-2015-0001/.12

factor of 65%. Outage information is covered extensively in the Rate Review Order, over pages65-72.Three key metrics for electric system performance are System Average Interruption DurationIndex (SAIDI), System Average Interruption Frequency Index (SAIFI), and Customer AverageInterruption Duration Index (CAIDI). For background on these metrics and why they arevaluable, see “Tracking the Reliability of the U.S. Electric Power System: An Assessment ofPublicly Available Information Reported to State Public Utility Commissions” from LawrenceBerkeley National Laboratory (LBNL). 9During the period measured, PREPA’s SAIFI was calculated at 11.61, which is an order ofmagnitude higher than the U.S. average. PREPA exceeded its SAIDI goal of 10 hours by 60%, agoal which was above the75th percentile of U.S. utilities. PREPA’s CAIDI was 180 minutes, upfrom 140 in 2013 - up nearly 30% since forbearance began. 10 The American Public PowerAssociation collects self-reported reliability data for publicly-owned utilities, “Evaluation ofData Submitted in APPA’s 2013 Distribution System Reliability & Operations Survey.” 11PREPA’s metrics exceed the averages and third quartile statistics for each of those categories.B2A. Reducing Political Influences Over Infrastructure DecisionsMost energy reform legislation in Puerto Rico has sought to reduce the political influence overPREPA’s decision-making, and the PREC addressed that topic as follows: “The quadrennial turnover of managers with each new political administration, the politicalpressures from elected officials to avoid necessary rate increases, the failure of governmentagencies to pay their electricity bills on time, the irresponsible initiation and termination ofexpensive capital projects, the high levels of electricity theft, the work rules that preventefficient use of well-paid employees, the poor recordkeeping and antiquated administrativeprocedure, the compensation schemes that prevent PREPA from recruiting and retainingqualified and experienced personnel – all this must come to a halt, to be replaced by auniversal commitment to the good of the Commonwealth.” Rate Review Order, pp. 23-24“This situation is not sustainable. Until PREPA’s financial situation improves, it cannotborrow new money. If it cannot borrow new money, 12 it cannot repair its deterioratingphysical infrastructure, prepare that infrastructure for a future of renewable energy, paysalaries sufficient to attract and keep excellent workers, and modernize its system so as toenable consumers to save money on their electric bills. The path to transforming PREPA intoa reliable, cost-effective, environmentally sound and customer-responsive company – df. See also, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, “IEEEBenchmark Year 2016 Results for 2015 Data”, hmarking-Results2015.pdf.10"Final Resolution and Order: PREPA Rate Review," Docket CEPR-AR-2015-0001, dated January 10, 2017(“Rate Review Order”), available on www.energia.pr.gov, 12PREPA entered Title III of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) inApril 2017.13

company central to Puerto Rico’s economic recovery – must begin with a plan for stabilizingPREPA’s finances.” 13B3. Assumptions on DemandBefore its economic crisis, thepopulation size of Puerto Rico wascomparable to Oregon, three times thatof Hawaii and five times that of Alaska.Currently, its GDP per capita is lowerthan any state. Similarly, while theUnited States ranks near the top in theWorld Bank’s “Doing Business”metrics, Puerto Rico sits at 64. 14Sustained economic hardship on theisland has accelerated the out migrationof citizens which had already resulted inan estimated 500,000 people departingFigure 4: Puerto Rico Economic Activity Index, from Governmentfor the mainland in the past decade.Development Bank of Puerto RicoEarly estimates suggestedapproximately 100,000 people have fled Puerto Rico since Hurricanes Irma and Maria hit. 15Puerto Rico has five times the combined populations of the territories and Freely AssociatedStates. Although median income is comparable to the other insular areas, Puerto Rico hasmaintained a manufacturing base, dependent in part on favorable treatment under the federal taxcode. As a consequence, the Puerto Rico energy system is larger than all of the others combinedby installed capacity.In its pre-storm Fiscal Plan, PREPA predicts just over 13,000,000 MWh sales in 2026, roughlyequivalent to 1500MW average load and 2250MW peak. A similar number was released in theFiscal Plan from early 2018. Given that existing installed capacity exceeds 5,000MW, and theexisting transmission system was designed to accommodate this capacity, significant declines toload in the next 10-15 years will be an important consideration for future investment plans.These portfolio considerations underscore the need to further analyze power flow, productioncost, and other scenarios, to provide reasonable amount of certainty that any investments are welltargeted and integrated into cost-reflective tariffs to support an affordable and reliable powersystem.B3A. Energy

and line workers, driven by a variety of factors, has accelerated in pace from 2010 through the close of 2017, with more Puerto Ricans now living in the continental United States than in the Commonwealth. The loss of human capital caused by this out-migration will further challenge Puerto Rico's ability to re-start its economy.