Transcription

Euclidean Geometry inMathematical OlympiadsWith 248 Illustrations

c 2016 by The Mathematical Association of America (Incorporated)Library of Congress Control Number: 2016933605Print ISBN: 978-0-88385-839-4Electronic ISBN: 978-1-61444-411-4Printed in the United States of AmericaCurrent Printing (last digit):10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Euclidean Geometry inMathematical OlympiadsWith 248 IllustrationsEvan ChenPublished and Distributed byThe Mathematical Association of America

Council on Publications and CommunicationsJennifer J. Quinn, ChairCommittee on BooksJennifer J. Quinn, ChairMAA Problem Books Editorial BoardGail S Nelson, EditorClaudi AlsinaScott AnninAdam H. BerlinerJennifer Roche BowenDouglas B. MeadeJohn H. RickertZsuzsanna SzaniszloEric R. WestlundMAA PROBLEM BOOKS SERIESProblem Books is a series of the Mathematical Association of America consisting ofcollections of problems and solutions from annual mathematical competitions; compilationsof problems (including unsolved problems) specific to particular branches of mathematics;books on the art and practice of problem solving, etc.Aha! Solutions, Martin EricksonThe Alberta High School Math Competitions 1957–2006: A Canadian Problem Book,compiled and edited by Andy LiuThe Contest Problem Book VII: American Mathematics Competitions, 1995–2000 Contests,compiled and augmented by Harold B. ReiterThe Contest Problem Book VIII: American Mathematics Competitions (AMC 10), 2000–2007, compiled and edited by J. Douglas Faires & David WellsThe Contest Problem Book IX: American Mathematics Competitions (AMC 12), 2000–2007,compiled and edited by David Wells & J. Douglas FairesEuclidean Geometry in Mathematical Olympiads, by Evan ChenFirst Steps for Math Olympians: Using the American Mathematics Competitions, by J.Douglas FairesA Friendly Mathematics Competition: 35 Years of Teamwork in Indiana, edited by RickGillmanA Gentle Introduction to the American Invitational Mathematics Exam, by Scott A. AnninHungarian Problem Book IV, translated and edited by Robert Barrington Leigh and AndyLiu

The Inquisitive Problem Solver, Paul Vaderlind, Richard K. Guy, and Loren C. LarsonInternational Mathematical Olympiads 1986–1999, Marcin E. KuczmaMathematical Olympiads 1998–1999: Problems and Solutions From Around the World,edited by Titu Andreescu and Zuming FengMathematical Olympiads 1999–2000: Problems and Solutions From Around the World,edited by Titu Andreescu and Zuming FengMathematical Olympiads 2000–2001: Problems and Solutions From Around the World,edited by Titu Andreescu, Zuming Feng, and George Lee, Jr.A Mathematical Orchard: Problems and Solutions, by Mark I. Krusemeyer, George T.Gilbert, and Loren C. LarsonProblems from Murray Klamkin: The Canadian Collection, edited by Andy Liu and BruceShawyerTrigonometry: A Clever Study Guide, by James TantonThe William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition Problems and Solutions: 1938–1964, A. M. Gleason, R. E. Greenwood, L. M. KellyThe William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition Problems and Solutions: 1965–1984, Gerald L. Alexanderson, Leonard F. Klosinski, and Loren C. LarsonThe William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition 1985–2000: Problems, Solutions,and Commentary, Kiran S. Kedlaya, Bjorn Poonen, Ravi VakilUSA and International Mathematical Olympiads 2000, edited by Titu Andreescu andZuming FengUSA and International Mathematical Olympiads 2001, edited by Titu Andreescu andZuming FengUSA and International Mathematical Olympiads 2002, edited by Titu Andreescu andZuming FengUSA and International Mathematical Olympiads 2003, edited by Titu Andreescu andZuming FengUSA and International Mathematical Olympiads 2004, edited by Titu Andreescu, ZumingFeng, and Po-Shen LohMAA Service CenterP.O. Box 91112Washington, DC 20090-11121-800-331-1MAAFAX: 1-240-396-5647

Dedicated to theMathematical Olympiad Summer Program

ContentsPrefacexiPreliminariesxiii0.1 The Structure of This Book . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xiii0.2 Centers of a Triangle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xiv0.3 Other Notations and Conventions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xvI Fundamentals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11 Angle Chasing1.1 Triangles and Circles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.2 Cyclic Quadrilaterals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.3 The Orthic Triangle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.4 The Incenter/Excenter Lemma . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.5 Directed Angles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.6 Tangents to Circles and Phantom Points . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.7 Solving a Problem from the IMO Shortlist . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.8 Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .33679111516182 Circles2.1 Orientations of Similar Triangles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2.2 Power of a Point . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2.3 The Radical Axis and Radical Center . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2.4 Coaxial Circles. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2.5 Revisiting Tangents: The Incenter . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2.6 The Excircles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2.7 Example Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2.8 Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2323242630313234393 Lengths and Ratios3.1 The Extended Law of Sines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3.2 Ceva’s Theorem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3.3 Directed Lengths and Menelaus’s Theorem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3.4 The Centroid and the Medial Triangle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4343444648vii

viiiContents3.53.63.7Homothety and the Nine-Point Circle. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49Example Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 564 Assorted Configurations4.1 Simson Lines Revisited . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.2 Incircles and Excircles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.3 Midpoints of Altitudes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.4 Even More Incircle and Incenter Configurations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.5 Isogonal and Isotomic Conjugates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.6 Symmedians . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.7 Circles Inscribed in Segments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.8 Mixtilinear Incircles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.9 Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .59596062636364666870II Analytic Techniques . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 735 Computational Geometry5.1 Cartesian Coordinates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.2 Areas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.3 Trigonometry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.4 Ptolemy’s Theorem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.5 Example Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.6 Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .757577798184916 Complex Numbers956.1 What is a Complex Number? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 956.2 Adding and Multiplying Complex Numbers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 966.3 Collinearity and Perpendicularity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 996.4 The Unit Circle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1006.5 Useful Formulas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1036.6 Complex Incenter and Circumcenter . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1066.7 Example Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1086.8 When (Not) to use Complex Numbers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1156.9 Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1157 Barycentric Coordinates1197.1 Definitions and First Theorems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1197.2 Centers of the Triangle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1227.3 Collinearity, Concurrence, and Points at Infinity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1237.4 Displacement Vectors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1267.5 A Demonstration from the IMO Shortlist . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1297.6 Conway’s Notations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1327.7 Displacement Vectors, Continued . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1337.8 More Examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1357.9 When (Not) to Use Barycentric Coordinates. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1427.10 Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143

ContentsixIII Farther from Kansas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1478 Inversion1498.1 Circles are Lines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1498.2 Where Do Clines Go?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1518.3 An Example from the USAMO . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1548.4 Overlays and Orthogonal Circles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1568.5 More Overlays . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1598.6 The Inversion Distance Formula . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1608.7 More Example Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1608.8 When to Invert . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1658.9 Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1659 Projective Geometry1699.1 Completing the Plane . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1699.2 Cross Ratios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1709.3 Harmonic Bundles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1739.4 Apollonian Circles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1769.5 Poles/Polars and Brocard’s Theorem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1789.6 Pascal’s Theorem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1819.7 Projective Transformations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1839.8 Examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1859.9 Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19010 Complete Quadrilaterals19510.1 Spiral Similarity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19610.2 Miquel’s Theorem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19810.3 The Gauss-Bodenmiller Theorem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19810.4 More Properties of General Miquel Points . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20010.5 Miquel Points of Cyclic Quadrilaterals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20110.6 Example Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20210.7 Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20511 Personal Favorites209IV Appendices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 213Appendix A: An Ounce of Linear Algebra215A.1 Matrices and Determinants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 215A.2 Cramer’s Rule . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 217A.3 Vectors and the Dot Product . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 217Appendix B: Hints221Appendix C: Selected Solutions241C.1 Solutions to Chapters 1–4 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 241C.2 Solutions to Chapters 5–7 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 251

xContentsC.3 Solutions to Chapters 8–10 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 272C.4 Solutions to Chapter 11 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 283Appendix D: List of Contests and AbbreviationsBibliographyIndexAbout the Author303305307311

PrefaceGive him threepence, since he must make gain out of what he learns.Euclid of AlexandriaThis book is an outgrowth of five years of participating in mathematical olympiads, wheregeometry flourishes in great vigor. The ideas, techniques, and proofs come from countlessresources—lectures at MOP resources found online, discussions on the Art of ProblemSolving site, or even just late-night chats with friends. The problems are taken from contestsaround the world, many of which I personally solved during the contest, and even a coupleof which are my own creations.As I have learned from these olympiads, mathematical learning is not passive—the onlyway to learn mathematics is by doing. Hence this book is centered heavily around solvingproblems, making it especially suitable for students preparing for national or internationalolympiads. Each chapter contains both examples and practice problems, ranging from easyexercises to true challenges.Indeed, I was inspired to write this book because as a contestant I did not find anyresources I particularly liked. Some books were rich in theory but contained few challenging problems for me to practice on. Other resources I found consisted of hundreds ofproblems, loosely sorted in topics as broad as “collinearity and concurrence”, and lackingany exposition on how a reader should come up with the solutions in the first place. I havethus written this book keeping these issues in mind, and I hope that the structure of thebook reflects this.I am indebted to many people for the materialization of this text. First and foremost, Ithank Paul Zeitz for the careful advice he provided that led me to eventually publish thisbook. I am also deeply indebted to Chris Jeuell and Sam Korsky whose careful readings ofthe manuscript led to hundreds of revisions and caught errors. Thanks guys!I also warmly thank the many other individuals who made suggestions and commentson early drafts. In particular, I would like to thank Ray Li, Qing Huang, and Girish Venkatfor their substantial contributions, as well as Jingyi Zhao, Cindy Zhang, and Tyler Zhu,among many others. Of course any remaining errors were produced by me and I acceptsole responsibility for them. Another special thanks also to the Art of Problem Solving fora, The Mathematical Olympiad Summer Program, which is a training program for the USA team at theInternational Mathematical Olympiad.xi

xiiPrefacefrom which countless problems in this text were discovered and shared. I would also liketo acknowledge Aaron Lin, who I collaborated with on early drafts of the book.Finally, I of course need to thank everyone who makes the mathematical olympiadspossible—the students, the teachers, the problem writers, the coaches, the parents. Mathcontests not only gave me access to the best peer group in the world but also pushed meto limits that I never could have dreamed were possible. Without them, this book certainlycould not have been written.Evan ChenFremont, CA

Preliminaries0.1 The Structure of This BookLoosely, each of the chapters is divided into the following parts.r A theoretical portion, describing a set of related theorems and tools,r One or more examples demonstrating the application of these tools, andr A set of several practice problems.The theoretical portion consists of theorems and techniques, as well as particular geometric configurations. The configurations typically reappear later on, either in the proofof another statement or in the solutions to exercises. Consequently, recognizing a givenconfiguration is often key to solving a particular problem. We present the configurationsfrom the same perspective as many of the problems.The example problems demonstrate how the techniques in the chapter can be used tosolve problems. I have endeavored to not merely provide the solution, but to explain howit comes from, and how a reader would think of it. Often a long commentary precedes theactual formal solution, and almost always this commentary is longer than the solution itself.The hope is to help the reader gain intuition and motivation, which are indispensable forproblem solving.Finally, I have provided roughly a dozen practice problems at the end of each chapter.The hints are numbered and appear in random order in Appendix B, and several of thesolutions in Appendix C. I have also tried to include the sources of the problems, so that adiligent reader can find solutions online (for example on the Art of Problem Solving forums,www.aops.com). A full listing of contest acronyms appears in Appendix D.The book is organized so that earlier chapters never require material from later chapters.However, many of the later chapters approximately commute. In particular, Part III does notrely on Part II. Also, Chapters 6 and 7 can be read in either order. Readers are encouragedto not be bureaucratic in their learning and move around as they see fit, e.g., skippingcomplicated sections and returning to them later, or moving quickly through familiarmaterial.xiii

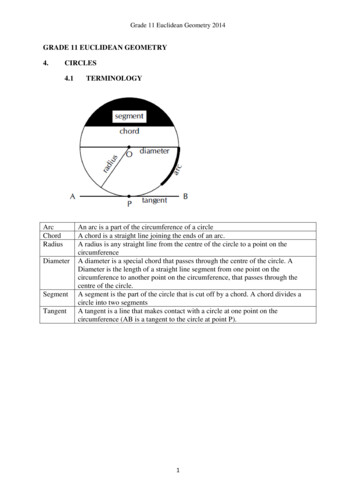

xivPreliminaries0.2 Centers of a TriangleThroughout the text we refer to several centers of a triangle. For your reference, we definethem here.It is not obvious that these centers exist based on these definitions; we prove this inChapter 3. For now, you should take their existence for granted.AAGHBCBAAOBCICBCFigure 0.2A. Meet the family! Clockwise from top left: the orthocenter H , centroid G, incenter I ,and circumcenter O.r The orthocenter of ABC, usually denoted by H , is the intersection of the perpendiculars (or altitudes) from A to BC, B to CA, and C to AB. The triangle formed by thefeet of these altitudes is called the orthic triangle.r The centroid, usually denoted by G, is the intersection the medians, which are the linesjoining each vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side. The triangle formed by themidpoints is called the medial triangle.r Next, the incenter, usually denoted by I , is the intersection of the angle bisectors of theangles of ABC. It is also the center of a circle (the incircle) tangent to all three sides.The radius of the incircle is called the inradius.r Finally, the circumcenter, usually denoted by O, is the center of the unique circle (thecircumcircle) passing through the vertices of ABC. The radius of this circumcircle iscalled the circumradius.

xv0.3. Other Notations and ConventionsThese four centers are shown in Figure 0.2A; we will encounter these remarkable pointsagain and again throughout the book.0.3 Other Notations and ConventionsConsider a triangle ABC. Throughout this text, let a BC, b CA, c AB, and abbreviate A BAC, B CBA, C ACB (for example, we may write sin 12 A forsin 12 BAC). We lets 1(a b c)2denote the semiperimeter of ABC.Next, define [P1 P2 . . . Pn ] to be the area of the polygon P1 P2 . . . Pn . In particular,[ABC] is area of ABC. Finally, given a sequence of points P1 , P2 , . . . , Pn all lying onone circle, let (P1 P2 . . . Pn ) denote this circle.We use to distinguish a directed angle from a standard angle . (Directed angles aredefined in Chapter 1.) Angles are measured in degrees.Finally, we often use the notation AB to denote either the segment AB or the line AB;the use should be clear from context. In the rare case we need to make a distinction weexplicitly write out “line AB” or “segment AB”. Beginning in Chapter 9, we also use theshorthand AB CD for the intersection of the two lines AB and CD.In long algebraic computations which have some amount of symmetry, we may usecyclic sum notation as follows: the notation f (a, b, c)cycis shorthand for the cyclic sumf (a, b, c) f (b, c, a) f (c, a, b).For example, cyca 2 b a 2 b b2 c c2 a.

Part IFundamentals1

CHAPTER1Angle ChasingThis is your last chance. After this, there is no turning back. You take the blue pill—thestory ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. Youtake the red pill—you stay in Wonderland and I show you how deep the rabbit-holegoes.Morpheus in The MatrixAngle chasing is one of the most fundamental skills in olympiad geometry. For that reason,we dedicate the entire first chapter to fully developing the technique.1.1 Triangles and CirclesConsider the following example problem, illustrated in Figure 1.1A.Example 1.1. In quadrilateral W XY Z with perpendicular diagonals (as in Figure 1.1A),we are given W ZX 30 , XW Y 40 , and W Y Z 50 .(a) Compute Z.(b) Compute X.W40 30 X50 YZFigure 1.1A. Given these angles, which other angles can you compute?You probably already know the following fact:Proposition 1.2 (Triangle Sum).The sum of the angles in a triangle is 180 .3

41. Angle ChasingAs it turns out, this is not sufficient to solve the entire problem, only the first half. Thenext section develops the tools necessary for the second half. Nevertheless, it is perhapssurprising what results we can derive from Proposition 1.2 alone. Here is one of the moresurprising theorems.Theorem 1.3 (Inscribed Angle Theorem).subtends an arc with measure 2 ACB.If ACB is inscribed in a circle, then itProof. Draw in OC. Set α ACO and β BCO, and let θ α β.CθO2θABFigure 1.1B. The inscribed angle theorem.We need some way to use the condition AO BO CO. How do we do so? Usingisosceles triangles, roughly the only way we know how to convert lengths into angles.Because AO CO, we know that OAC OCA α. How does this help? UsingProposition 1.2 gives AOC 180 ( OAC OCA) 180 2α.Now we do exactly the same thing with B. We can derive BOC 180 2β.Therefore, AOB 360 ( AOC BOC) 360 (360 2α 2β) 2θand we are done.We can also get information about the centers defined in Section 0.2. For example,recall the incenter is the intersection of the angle bisectors.Example 1.4. If I is the incenter of ABC then1 BI C 90 A.2

51.1. Triangles and CirclesProof. We have BI C 180 ( I BC I CB)1 180 (B C)21 180 (180 A)21 90 A.2AIBCFigure 1.1C. The incenter of a triangle.Problems for this SectionProblem 1.5. Solve the first part of Example 1.1. Hint: 185Problem 1.6. Let ABC be a triangle inscribed in a circle ω. Show that AC CB if andonly if AB is a diameter of ω.Problem 1.7. Let O and H denote the circumcenter and orthocenter of an acute ABC,respectively, as in Figure 1.1D. Show that BAH CAO. Hints: 540 373AHBOCFigure 1.1D. The orthocenter and circumcenter. See Section 0.2 if you are not familiar with these.

61. Angle Chasing1.2 Cyclic QuadrilateralsThe heart of this section is the following proposition, which follows directly from theinscribed angle theorem.Proposition 1.8. Let ABCD be a convex cyclic quadrilateral. Then ABC CDA 180 and ABD ACD.Here a cyclic quadrilateral refers to a quadrilateral that can be inscribed in a circle.See Figure 1.2A. More generally, points are concyclic if they all lie on some circle.BBAACDCDFigure 1.2A. Cyclic quadrilaterals with angles marked.At first, this result seems not very impressive in comparison to our original theorem.However, it turns out that the converse of the above fact is true as well. Here it is moreexplicitly.Theorem 1.9 (Cyclic Quadrilaterals). Let ABCD be a convex quadrilateral. Then thefollowing are equivalent:(i) ABCD is cyclic.(ii) ABC CDA 180 .(iii) ABD ACD.This turns out to be extremely useful, and several applications appear in the subsequentsections. For now, however, let us resolve the problem we proposed at the beginning.W30 40 40 X50 YZFigure 1.2B. Finishing Example 1.1. We discover W XY Z is cyclic.

71.3. The Orthic TriangleSolution to Example 1.1, part (b). Let P be the intersection of the diagonals. Then wehave P ZY 90 P Y Z 40 . Add this to the figure to obtain Figure 1.2B.Now consider the 40 angles. They satisfy condition (iii) of Theorem 1.9. That meansthe quadrilateral W XY Z is cyclic. Then by condition (ii), we know X 180 ZYet Z 30 40 70 , so X 110 , as desired.In some ways, this solution is totally unexpected. Nowhere in the problem did theproblem mention a circle; nowhere in the solution does its center ever appear. And yet,using the notion of a cyclic quadrilateral reduced it to a mere calculation, whereas theproblem was not tractable beforehand. This is where Theorem 1.9 draws its power.We stress the importance of Theorem 1.9. It is not an exaggeration to say that morethan 50% of standard olympiad geometry problems use it as an intermediate step. We willsee countless applications of this theorem throughout the text.Problems for this SectionProblem 1.10. Show that a trapezoid is cyclic if and only if it is isosceles.Problem 1.11. Quadrilateral ABCD has ABC ADC 90 . Show that ABCD iscyclic, and that (ABCD) (that is, the circumcircle of ABCD) has diameter AC.1.3 The Orthic TriangleIn ABC, let D, E, F denote the feet of the altitudes from A, B, and C. The DEF iscalled the orthic triangle of ABC. This is illustrated in Figure 1.3A.AEFBHDCFigure 1.3A. The orthic triangle.It also turns out that lines AD, BE, and CF all pass through a common point H , whichis called the orthocenter of H . We will show the orthocenter exists in Chapter 3.

81. Angle ChasingAlthough there are no circles drawn in the figure, the diagram actually contains sixcyclic quadrilaterals.Problem 1.12. In Figure 1.3A, there are six cyclic quadrilaterals with vertices in{A, B, C, D, E, F, H }. What are they? Hint: 91To get you started, one of them is AF H E. This is because AF H AEH 90 ,and so we can apply (ii) of Theorem 1.9. Now find the other five!Once the quadrilaterals are found, we are in a position of power; we can apply anypart of Theorem 1.9 freely to these six quadrilaterals. (In fact, you can say even more—theright angles also tell you where the diameter of the circle is. See Problem 1.6.) Upon cl

Euclidean Geometry in Mathematical Olympiads,byEvanChen First Steps for Math Olympians: Using the American Mathematics Competitions,byJ. Douglas Faires . This book is an outgrowth of five years of participating in mathematical olympiads, where geometry flourishes in great vigor. The ideas, techniques, and proofs come from countless