Transcription

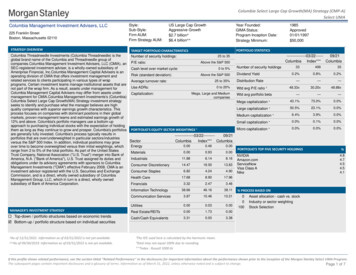

Graham & DoddsvilleAn investment newsletter from the students of Columbia Business SchoolIssue XVIInside this issue:Joel GreenblattP. 1LoewsCorporationP. 1Royce &AssociatesP. 1Omaha DinnerP. 3Fall 2012Joel Greenblatt— “ThoughtProcess andClarity are Key”LoewsCorporation—“Patience ispart of ourDNA”Joe Rosenberg and Jim TischEditorsJay Hedstrom, CFAMBA 2013Jake LubelMBA 2013Sachee TrivediMBA 2013Richard HuntMBA 2014Stephen LieuMBA 2014Visit us ents/organizations/cima/Joel GreenblattJoel Greenblatt is theManaging Partner ofGotham Capital, an investment firm he foundedin 1985, and a ManagingPrincipal of Gotham Asset Management. Mr.Greenblatt is the authorof four investing-relatedbooks, including the NewYork Times bestseller TheLittle Book that Beats theMarket and You Can Be aStock Market Genius. Mr.Greenblatt is the formerChairman of Alliant Techsystems, a Fortune 500company and the currentChairman of SuccessCharter Network, a network of charter schools inNew York City. He is anAdjunct Professor in Finance at Columbia Business School and a graduate of the Wharton MBAprogram.(Continued on page 4)Loews Corporation is one of the largest diversified holding companies in the United States. Since its foundingin 1959, Loews has been rooted in the principles of valueinvesting as a means of generating wealth for its shareholders. CEO Jim Tisch (one of three members of thecompany’s Office of the President along with his brotherAndrew and cousin Jonathan) and Chief InvestmentStrategist Joe Rosenberg shared their thoughts and experiences with G&D.(Continued on page 14)Royce & Associates —Legendary Small Cap InvestorsCharlie Dreifus, Chuck Royce, Buzz Zaino, Whitney GeorgeRoyce & Associates, investment advisor to The RoyceFunds, is one of the industry’s most experienced andhighly respected small-cap investment managers. Founded in 1972, Royce & Associates has producedoutstanding returns over its 40 year history by maintaining its value-oriented discipline regardless of marketmovements and trends. G&D sat down for a group interview with portfolio managers Chuck Royce, CharlieDreifus, Whitney George, and Buzz Zaino.(Continued on page 23)

Page 2Welcome to Graham & DoddsvillePictured: Bruce Greenwald atthe Columbia Student Investment Management Conferencein February 2012.The Heilbrunn Center sponsorsthe Applied Value Investing program, a rigorous academic curriculum for particularly committed students that is taught bysome of the industry’s best practitioners.Pictured: Heilbrunn CenterDirector Louisa Serene Schneider at the CSIMA conference inFebruary 2012.Louisa skillfully leads the Heilbrunn Center, cultivating strongrelationships with some of theworld’s most experienced valueinvestors and creating numerouslearning opportunities for students interested in value investing. The classes sponsored bythe Heilbrunn Center are amongthe most heavily demanded andhighly rated classes at ColumbiaBusiness School.WelcomeWeare pleasedback totoanotherpresent yearyouwithofGrahamIssue XV& Doddsville.of Graham &WeDoddsville,aredelightedColumbiato bringBusinessto youSchool’sthe16th editionstudent-ledof Columbiainvestment newsletter,BusinessSchool’s co-sponsoredstudent-ledby the Heilbrunninvestmentnewsletter,CentercoforGraham & Doddsponsoredby theInvestingHeilbrunnandthe ColumbiaCenterfor GrahamStudent& DoddInvestment ManagementInvestingand the ColumbiaAssociation.Student Investment ManagementTOO Association.ADDNowits freeseventhyear, GraPleaseinfeelto contactus ifham& Doddsvilleis stillgoingyou havecommentsor ideasstrong.Wewould like Weto offerabout thenewsletter.ahopespecialto Jaspan,& Doddsville asandmuchwelastyear’seditors,for showingenjoyputtingit together!us the ropes and ensuring thattheproductpresentedto you- Editors,Graham& Doddsvillelast year, in three spectacularissues, was of the highest quality. We would also like torecognize Graham &Doddsville’s founders, JosephEsposito, Abigail Corcoran, andDavid Kessler. What you arereading today is a product oftheir initiative and inspiration.Now on to our distinguishedand diverse lineup of successfulvalue investors as well as someof the interesting topics youwill see them address in thefollowing pages. Joel Greenblatt, now in his 17th year asan adjunct member of the Columbia Business School faculty,describes his shift from specialsituations investing to a formula-based approach. He describes how the most glaringinefficiencies in the markettoday are caused by a widespread focus on very shortterm performance which isn’tlikely to abate any time soon.Mr. Greenblatt notes that despite the market’s run thisyear, he still believes it is cheapbased upon the measures thathe follows.Jim Tisch and JoeRosenberg from Loews Corporation detail some of thehistory behind a few of theirbest investments. Mr. Tischexpands on the importancepermanent capital has had onhis investment style and theinherent dangers in acquiringcompanies. Mr. Rosenberg,who recently celebrated his50th year on Wall Street, recounts how he got started inthe industry. He also shareswith us his introduction toLarry Tisch many years ago andwhat brought him to Loews,his home since 1973.We were also extremely fortu-Alex Porter and Jon Friedland of PorterOrlin with the first and second placefinishers at the Moon Lee PrizeCompetition which was held in January2012 at Columbia Business Schoolnate to be granted a group interview with Chuck Royce,Whitney George, CharlieDreifus, and Buzz Zainofrom Royce & Associates. Thisquartet of legendary small capinvestors speaks candidly aboutthe similarities and differences oftheir respective investmentstyles – from the importance ofmeeting with management tothe safety of a clean balancesheet. They also detail howthey believe small-cap investinghas changed over time, and howit has impacted where they findideas.This issue also contains picturesfrom the 2012 “From Grahamto Buffett and Beyond” Dinner,which takes place each May inOmaha, Nebraska. We thankour featured investors for sharing their time and insights withour readers. Please feel free tocontact us if you have commentsor ideas about the newsletter aswe continue to refine this publication for future editions. Wehope you enjoy reading thisissue of Graham & Doddsville asmuch as we have enjoyed putting it together.- G&Dsville EditorsPanelist of Judges at the Pershing SquareValue Investing and PhilanthropyChallenge which was held in April 2012at the Center for Jewish History

Page 32012 “From Graham to Buffett and Beyond” Dinner, OmahaPanel: Prof. Greenwald, Mario Gabelli, David Winters, Tom RussoRusso explaining NestleWinters answering a questionGabelli with Columbia students and Louisa SchneiderGreenwald making a pointRusso posing with audienceGabelli in a light moment

Page 4Joel Greenblatt(Continued from page 1)G&D: Professor Greenblatt, what was your introduction to investing andwho were some investorswho directly or indirectlyinfluenced you early in yourcareer?Joel GreenblattJG: I went to Wharton,and, as they still do today,they taught the efficientmarket theory. This didn’tresonate with me all thatwell. Then, I think when Iwas a junior, I read an article in Forbes about BenGraham. The article outlined how he had this formula to beat the market,provided an explanation ofhis thought process, anddescribed “Mr. Market” alittle bit. I read that articleand a light bulb went off – Ithought: “boy, this finallymakes some sense to me.”I started reading everythingI could by Benjamin Graham. I also read a bookcalled Psychology and theStock Market by David Dreman. He was one of thefirst people to focus on behavioral finance and wasreally ahead of his time. Istarted reading about Buffett and his letters. All thatstuff resonated very wellwith me. I would say thatI’m self-taught in that sense.I learned the basics, I understood how to tear apartbalance sheets, incomestatements, and cash flowstatements from school andfrom growing up in a business family, but my understanding of the stock marketreally came from my ownindependent reading.“ when I was ajunior, I read anarticle in Forbesabout Ben Graham.The article outlinedhow he had thisformula to beat themarket, provided anexplanation of histhought process, anddescribed “Mr.Market” a little bit. Iread that article anda light bulb went off –I thought: ‘boy, thisfinally makes somesense to me.’ ”G&D: You spent sometime with Richard Pzena,who happened to be thefirst interviewee for Graham& Doddsville, while at Wharton. Do you have any stories or anecdotes that youcould share from your timetogether at Wharton?JG: Sure. We were in thesame program and werealso the same year at Wharton. We were in an undergrad/grad program whereyou earned your MBA andundergraduate degrees infive years. We were in thatsame cohort. I becamefriendly with Rich in our lastyear as undergraduates.When we first joined thatprogram in our senior undergraduate year, I had toldhim about some of the reading I had done regardingGraham’s belief that formulas could be used to determine profitable investments.We decided to do a master’s thesis with anothergood friend of mine analyzing Graham’s approach. Atthe time, we didn’t haveaccess to a database ofstock market information.Standard and Poor’s used toput out a Stock Guide withsome balance sheet andincome statement information on about 5,000 companies monthly. The schoollibrary had about 10 years’worth of these guides.Not having access to a database, we actually went tothe library. We wanted togo back and test Graham’sformulas, so to speak. Sowe went to the library andmanually went through theS&P stock guides. Westarted with the A’s and B’s,which covered about 750companies, and analyzedeight or nine years’ worthof financial data. It was verytime intensive. Rich wasalso very good with computers. We had a DEC10computer that was about sixtimes the size of this room.Rich knew how to take thedata that we had all compiled and, with the littlepunch cards, get the datainto the computer. So wewere able to test some simple Graham formulas. Thatwork ended up actually get(Continued on page 5)

VolumeIssueXVII, Issue 2Page 5Joel Greenblatt(Continued from page 4)ting published in the Journalof Portfolio Management.G&D: How long did youspend on that?JG: That was many hours; Ireally couldn’t tell you. Iguess my time was cheaperback then!G&D: What inspired youto write You Can Be a StockMarket Genius?JG: The motivation for mewas the recognition that Ihad really learned about thebusiness from reading. Ithought it was pretty coolthat these investors hadbeen willing to share withreaders what they knew andhad learned during theircareers. I’m not a verygood listener, so I like tolearn by reading. When Iwas in school, there weretwo things that seemed likeinteresting pursuits if I everbecame successful: one wasto write and one was toteach.We ran outside capital atGotham Capital for tenyears and then returned theoutside capital in ‘94, thoughwe continued to run ourown money. We had beenquite successful during thattime and so I thought that ifI put together a group ofwar stories as examples anddescribed the principles thatI had used to make money,it would be very instructivefor people. I wanted towrite it in a friendly, accessible way so that individualinvestors could profit fromit as I had. I started writingthe book in ’95 or ‘96. Ialso started teaching at Columbia in ’96. I hadn’ttaught MBAs yet. So when Iwas writing the book, I didn’t realize that I was reallywriting it at an MBA level. Ihad assumed that because Ihad been doing it so long,individuals knew a lot morethan they actually do.So I ended up writing abook that most hedge fundmanagers have read, butone which was perhaps at alittle higher level than I hadintended. I wrote it accessibly, so I had fun writing it,but I think it was at more ofan MBA level, not just aregular investor level. Ithink that was a mistakethat I made because I waslooking to educate a muchmore needy bunch thanMBAs and hedge fund managers. That was really oneof the things that drove meto continue writing until Icould accomplish my original goal. I am very proud ofthat book, but I just thinkit’s written at such a levelthat you have to be fairlysophisticated in financialanalysis, at least, to fullyprofit from its advice.G&D: Given the proliferation of hedge funds sincethe Stock Market Genius’srelease, are the opportunities in some of those sametypes of special situationssimilarly available today?JG: I think they are. I thinkthere are always opportunities. What happens to people who become very goodat special situation investingis that they make a lot ofmoney, and then they get alittle too big to invest insome of the smaller situations that are out there. Inthe book I wrote that someof these opportunities areless liquid or smaller, so alot of people aren’t lookingat them as a result. I thinkin the book I said somethingto the effect of: “don’tworry about getting too bigfor these strategies until youget to about 250 million.When you get there, giveme a ring.” I would bumpthat number up to over 1billion today. You can’t run 10 billion and get ridiculous rates of return, mostlikely. A few people can,but they have a large staff,or they have concentratedpositions.There are still many strategies in that book that couldmake you a lot of money. Ithink that these opportunities are out there. Since Iwrote Stock Market Genius,we had an internet bubblewhere people were pricingthings stupidly, and then wehad 2008, where stockshalved and a few years laterthey doubled. So to sayassets were accuratelypriced all along, or thatthere were no opportunities, or that the marketdoesn’t get very emotionaland throw you opportunities, is kind of silly in mymind. That doesn’t make iteasy to tune out all of thenoise that’s out there, butthere are still ample opportunities that one can find.(Continued on page 6)“What happens topeople who becomevery good at specialsituation investing isthat they make alot of money, andthen they get alittle too big toinvest in some ofthe smallersituations that areout there.peoplearen’t looking atthem as a result.”

Page 6Joel Greenblatt(Continued from page 5)“I make aguarantee the firstday of class everyyear that if you’regood at valuingcompanies, themarket will agreewith you. I justdon’t guaranteewhen. It could be acouple weeks or itcould be two orthree years.My definition of value investing is figuring out whatsomething is worth and paying a lot less for it. I make aguarantee the first day ofclass every year that ifyou’re good at valuing companies, the market will agreewith you. I just don’t guarantee when. It could be acouple weeks or it could betwo or three years. Andthe corollary is simply that,in the vast majority of cases,two or three years isenough time for the marketto recognize the value thatyou see, if you’ve done goodvaluation work. When youput together a group ofcompanies, that process canoften happen a lot faster, onaverage. One argument Imake in another one of mybooks (which few haveread), called The Big Secretfor the Small Investor, is thatthe world has becomemuch more institutionalizedover the years, even morethan it was when I wroteYou Can Be a Stock MarketGenius, and that is a realadvantage for longer-terminvestors. For institutionalinvestors, you can track allmoney flows by one simplemetric – which managersdid well last year and whichdid poorly. Managers whodid well last year attract allthe money and managerswho did poorly lose themoney.If you’re an active manager,you may have a long-termhorizon but your clientsprobably don’t. So, mostmanagers feel that theyneed to make money overthe short term. Therefore,professionals systematicallyavoid companies that areperhaps not going to do aswell in the short term. Insome ways, there’s actuallymore opportunity in thoseareas now than ever beforedue to the greater institutionalization of the market.True, there are some areasthat are more followed. Forinstance, I wrote about spinoffs in Stock Market Genius.Of course a lot of peoplefollow spin-offs, yet if youlook at the studies, they stillseem to outperform themarket after they’re spunoff. Certainly a lot of thesmaller situations are thesituations where there is ahuge dichotomy in size orpopularity between the parent company and the spinoff. These opportunities arestill there, partly becausesome are too small for mostfirms to take advantage of.Other opportunities are theresult of volatile emotions inthe market. Given the institutionalization of the investor base, the fact that markets are emotional, and thefact that there are still lotsof nooks and crannies outthere that even successfulhedge funds can’t pursue,I’m not concerned aboutthe size of the existing opportunity set.G&D: Do you see anythingthat could lengthen institutional investors’ time horizons, thereby reducing the“time arbitrage” from whichmany value investors profit?JG: No, not really. Thereason is that there is anagency problem where thepeople who are allocatingthe capital are not makingthe investment decisions. Iwas talking to a gentlemanat one of the top endowments, and he said, “I wouldlike to tell you that we havea long-term horizon, because we should. But I’vebeen here 11 years, we’vehad three chief investmentofficers, and none of themleft after a period of positiveperformance.” JeremyGrantham spoke at a Graham and Dodd Breakfastseveral years ago and one ofhis lines that I thought wasfunny, and probably very,very accurate, was: “for thebest institutional investors,their time horizon is3.000000 years.” That isthe horizon for the best.For many institutional investors, it’s even shorter. So Ithink that’s about all youcan hope for as an investment manager.I think the reason for this isthat your investors – yourclients – generally just don’tknow what the investmentmanager’s logic was for eachinvestment. What they canview is performance. It’spretty clear that for mutualfunds, for instance, the performance of a given fundover the last 1, 3, 5, and 10years has very little correlation with the future performance for the next 1, 3,5, and 10 years. So institutional investors are left withpredicting who’s going to dowell in the future, whichthey attempt to do by looking at the manager’s proc(Continued on page 7)

VolumeIssueXVII, Issue 2Page 7Joel Greenblatt(Continued from page 6)ess. For most clients, themanager’s process is nottransparent and the rationale behind investment decisions is not clear. Clientstend to make decisions overmuch shorter time horizonsthan are necessary to judgeskill and judgment and otherthings of that nature. So Ithink time horizons are getting shorter, not longer.We’re not in danger of people expanding their timehorizons when they’re judging managers. I think timearbitrage will be the “lastman standing,” prettyclearly.G&D: Your career hasreally been, from an investment standpoint, composedof two parts. Earlier in yourcareer, you made moreconcentrated investments inspecial situations. Now, youinvest in a more diversifiedmanner in higher qualitycompanies. What drovethis shift?JG: I already talked aboutthe research we did on Graham’s strategies. Around2003, my partner, RobGoldstein, and I decided todo some research on ourown strategies, which hadevolved to resemble theway Buffett looks at theworld. Graham’s investment world view was to“buy it cheap.” Buffettadded a little twist thatprobably made him one ofthe richest people in theworld. He essentially said,“well if I can buy a goodbusiness cheap, that’s evenbetter.”So we tested the principlesbehind what we look atwhen we value companies.The results were very robust. My write-up of the“.those companiesthat were in the topdecile, based onquantitativemeasures indicatingthat they were bothcheap and good,performed betterthan those in thesecond decile, whichperformed betterthan those in thethird, and so on inorder. It was quitepowerful andsurprising. It juststarted us on a longpath of researchwhich tried tosystematize the waywe’d always valuedcompanies.”results of our very first testformed the basis for TheLittle Book That Beats theMarket. The upshot wasthat those companies thatwere in the top decile,based on quantitative measures indicating that theywere both cheap and good,performed better thanthose in the second decile,which performed betterthan those in the third, andso on in order. It was quitepowerful and surprising. Itjust started us on a longpath of research which triedto systematize the way we’dalways valued companies.We were able to achievevery robust long/short returns. We were able to addas much value on the shortside as we were on the longside. So we were able tocreate very diversified long/short portfolios with relatively smooth returns. Wedidn’t even know we coulddo that before seeing theresults of our research.There’s absolutely nothingwrong with what I wrote inYou Could Be a Stock MarketGenius – it’s what I did foralmost 30 years. But aboutthree or four years ago, mypartner and I decided thatconducting really in-depthresearch on a handful ofcompanies is a full-time jobif you want to do it well.Alternatively, more systematically valuing a large number of companies over timeis a huge job itself due torisk management and otherresponsibilities. Thoughthey’re a little different,both strategies are greatand they’re both full-timejobs. I had been doing onething for a long time and Iwas fascinated by our research results of the systematic valuation approach.(Continued on page 8)Pictured: Bill Miller of LeggMason Capital Managementat CSIMA Conference inFebruary 2012.

Page 8Joel Greenblatt(Continued from page 7)“Part of the futureis unknowable butthere are someinstances where youcan take acalculated risk/reward bet. Onething I would say isthat a commoncharacteristic ofmany of the stocksthat we buy is thateveryone hatesthem. We do that alot.”When you are very concentrated, you have the chanceto make 20, 30, 40% annualized returns. Perhaps if I’mwilling to accept somewhatlower returns, say midteens, and achieve asmoother return compounded at the same time,then that’s pretty attractivetoo. One approach is notbetter than the other.There’s an interesting tradeoff between how much volatility you’re willing to acceptand how much moneyyou’re potentially going tomake. If I were starting allover again, I’d do exactlywhat I did before. And nowthat we’re well established, Ithink the main attraction ofthe systematic approach isthat it’s something a bit newand different, although Iwould reiterate that it’sreally the same thing thatwe’ve always done with justa slightly different approach.G&D: We’ve heard otherinvestors who use theirown formulaic approach toinvesting say that, from timeto time, they get an itch tochange their model or tootherwise override it. Haveyou ever had this urge andis it difficult to resist?JG: The only way Rob and Iknow how to value companies is through variousmeasures of absolute andrelative value. Of course itwon’t work for every company, but on average itworks quite well. There aresome companies that webuy that might make youscratch your head. On theother hand, we’ve beenpretty good stock pickersover history, and we havenot been able to improveour results by picking thethings that we clearly don’twant. There’s a certainmedication on the marketthat’s made by a small pharmaceutical company. Thiscompany was considered avery attractive buy according to one of our screens.But I knew why it lookedcheap – its key medicationwas coming off of patent thenext year and the stock waspriced accordingly. My inclination could have possiblybeen to override the formulaic recommendation because I knew exactly whatwas going on. It wasn’t likeit was a big secret. I didn’toverride anything, however,and the company subsequently figured out a way toextend the patent a littlelonger which then led to adoubling of the stock priceover the next six months. Ithink that’s really been ourexperience. Part of thefuture is unknowable butthere are some instanceswhere you can take a calculated risk/reward bet. Onething I would say is that acommon characteristic ofmany of the stocks that webuy is that everyone hatesthem. We do that a lot.G&D: You mentioned taking short positions earlier.Can you be successful inthis area merely by shortingthe companies in the lowestdeciles of your screens –that is, by systematicallydoing the opposite of yourlong approach?JG: When we buy things,we like companies that invest their capital well; theygenerate large amounts ofcash flow relative to theprice we’re paying. On theshort side, we would like tobe short, in general, highpriced, cash-eating companies. So it is essentially theopposite of our long approach. You do have tobalance your risk, though.In the original edition of TheLittle Book That Beats theMarket, I grouped the“magic formula” stocks as Icalled them – or stockswhich were systematicallyconsidered good and cheap– into deciles. Decile onewas the best combination ofgood and cheap. Decile twowas the second best, andthe tenth decile was composed of companies thatearn lousy returns on tangible capital, yet neverthelesswere expensive. There wasa big performance spreadbetween decile one anddecile ten when we did thestudy, and it worked in order as I mentioned earlier.Decile one beat two, twobeat three, three beat four,all the way down throughdecile ten. Pretty muchevery student I’ve had, andhundreds of e-mails afterthe book was published,have said, “Joel, I have thisgreat idea for you. Whydon’t you buy decile oneand short decile ten? You’lltake out the market risk andyou’ll make 15% or 16% ayear.” I did that experimentin the afterword of the revised addition of The Little(Continued on page 9)

VolumeIssueXVII, Issue 2Page 9Joel Greenblatt(Continued from page 8)Book, and the resultsshowed that you couldn’tfigure out a compoundedrate of return because youlost all of your money.Somewhere around the firstquarter of 2000, the shortswent up a lot and the longswent down such that thecombined loss was so severe you went broke.There were a couple thingsa bit unfair about that because we kept the portfoliosfor a year, and we didn’t readjust as we lost money.What I was trying to showat a high level was that if Iwrote a book that had aformula and it worked everyday and every month andevery year, everyone woulduse it and it would stopworking. So, the magic formula, like all value investing,can give you noisy returnsover the short term, butthat’s also why it continuesto work.G&D: In class, you talkedabout how you try to assesshow cheap or expensive themarket is at any point intime. Can you talk aboutyour views on the markettoday and how you look atit?JG: Sure. Well we’velooked bottoms-up at eachstock in the Russell 1000Index, the thousand largeststocks in the U.S. by marketcap. We’ve looked at thoseover history, meaning themarket-cap-weighted freecash flow yield of the Russell 1000 on each day overthe last twenty years andright now we’re in aboutthe 87th percentile towardscheap, meaning that themarket as measured by theRussell 1000 on a free cashflow basis has only beencheaper 13% of the timeover the last 23 years.When it has been thischeap, the forward returnfor the Russell has beenabout 17% and then aboutthe mid-30’s two years out.That’s not to say that themarket’s prospects are better or worse going forward– they’re probably a littlebelow average for the forward period and thereforeyou could say that perhapsyou won’t do quite as wellas would be implied by historical returns. But, even inthe 50th percentile, youwould expect to make 8%or 9% based on the historyof the last twenty-somethingyears, so I would just saythat if I had a choice between being more long ormore short, I’d be morelong. It’s a very attractivetime to invest in the market,despite the run-ups thatwe’ve seen in the last year.one I choose works out. Itdoesn’t matter that I missedout on 11 or 12. Not losingmoney is a good way toensure that your portfoliohas a good risk/reward profile. One of the things I saidin You Can Be a Stock MarketGenius is if you don’t losemoney, most of the alternatives are good. Even if youdon’t know what the upsideis – if you just know there’supside – you can createscenarios where you havean excellent risk/reward.Positions with limited downside are the types of positions that I have loaded upon in the past. Not thepositions with the biggestpayoff. I could buy a lotknowing that I wouldn’t losemuch and that there weregood possibilities that it wasworth a lot more over time.At the very least, I knewthat my downside was wellprotected and so I couldcreate an asymmetric risk/reward by saying if I don’tlose much, there are notmany alternatives other thanto make money.G&D: Harkening back tothe first part of your investing career, you talked aboutpassing on ideas. Howmany ideas did you pass onfor every idea that youended up acting upon?Something else that I’ve saidin my class is that if you aretrying to analyze an investment and there’s a lot ofuncertainty regarding acompany – whether it’s newtechnology or new competitors, or something else – orthe industry in general isuncertain such that it’s veryhard to predict what’s goingto happen in the future, justskip that one and find oneyou can analyze. If you invest in six or eight thingsthat you’ve analyzed closely,JG: It’s a tough one. Iwould say it obviously depends on how selective youare. If I looked at 40 or 50ideas, and, while perhaps 12or 13 of them would haveworked out, if I end up onlybuying one, that’s okay.That’s fine as long as the(Continued on page 10)

Page 10Joel Greenblatt(Continued from page 9)“If you’re a longterm holder andyou own a chain ofstores in theMidwest andsomething badhappens to Greece,there may be somesmall impact, butyou’re not going tosell your businessfor half of what youthink it’s worth allof a sudden. If I’ma shareowner inbusinesses, I need tohave a long-termperspective thatthings will

Little Book that Beats the Market and You Can Be a Stock Market Genius. Mr. Greenblatt is the former Chairman of Alliant Tech-systems, a Fortune 500 company and the current Chairman of Success Charter Network, a net-work of charter schools in New York City. He is an Adjunct Professor in Fi-nance at Columbia Busi-ness School and a gradu-