Transcription

Building Alliances Series:EMERGENCIES

June 2009This publication was produced by the United States Agency forInternational Development. It was prepared by DAI and formatted byMW Studio.The GDA wishes to offer our profound appreciation to all the individualswho contributed their time and ideas towards its development, and specialthanks to Cecilia Brady, Laurie Pierce, Dan O’Brien and Ben Kauffeld fortheir efforts in research, design and drafting the guide.Photo Credits:Cover: OFDA, USAIDPage 0: USAIDPage 5: USAIDPage 7: World LearningPage 8: Sue McIntyre, USAIDPage 9: Jonathan Metzger, USAIDPage 11: USAIDPage 12: William Billingsley, Shelter for Life InternationalPage 14: USAID/ArmeniaPage 15: CAREPage 16: Alda Kauffeld, USAIDPage 17: Sue McIntyre, USAIDPage 18: Red CrossPage 19: USAIDPage 20-21: USAIDPage 22: Intel CorporationPage 23: USAIDPage 25: Mary Jordan, USAIDPage 27: Gennadiy Ratushenko, WorldbankPage 28: USAIDPage 29: USAIDPage 30: USAID/AfghanistanPage 31: USAID/OFDAPage 33: Thomas Hartwell, USAIDPage 34: USAIDPage 36: USAIDPage 38: USAIDInside back: USAID

CONTENTSGDA Sector Guide:Natural Disastersand ComplexEmergencies 1USAID’s response todisasters 2Alliance models innatural disastersand complexemergencies 4What private sectorindustries maycollaborate? 20Finding a goodpartner 22Other resources tohelp identify privatesector partners 24What partners canoffer 26Issues to watch/Lessonslearned 28Eight things to dobefore disasterstrikes 32Five things to do duringan emergency 36Other resources 37Natural disaster casestudy 39Complex emergencycase study 40

GDA SECTOR GUIDE:NATURAL DISASTERS ANDCOMPLEX EMERGENCIESWelcome USAID Alliance Builders!Public-private partnerships done right are a powerful tool for development,providing enduring solutions to some of our greatest challenges. To helpfamiliarize you with the art of alliance building, the Global DevelopmentAlliance (GDA) office has created a series of practical guides that highlightproven practices in partnerships, demonstrate lessons learned, andprovide insight on the identification and design of strategic partnershipsthat meet your sector-focused development objectives.*The purpose of this guide is to show you how to build public-privatepartnerships in Natural Disasters and Complex Emergencies. This guideis specifically designed for US Government technical officers (includingofficers of the Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistancebureaus and Mission Disaster Response Officers) responsible for crisis**preparedness and response and overall emergency management. Whetheryou are new to using alliances in this sector or a seasoned expert, inthe following pages you will find tips, resources, and information that aredesigned to assist you in building alliances to meet the challenges you arefacing.While this guide is meant to promote your partnership efforts for NaturalDisaster and Complex Emergencies, additional resources and guidanceare available to you on the GDA website: http://usaid.gov/GDA or IF YOU ARE IN A LOCATIONTHAT HAS JUST EXPERIENCEDA CRISIS OR DISASTER,PLEASE START ON PAGE 36* The terms “alliance” and “partnership” areused interchangeably in this guide, but bothterms refer to the type of collaborationthat can be designated as a GDA.** The term “crisis” encompasses bothnatural disasters and man-made complexemergencies. 1

USAID’S RESPONSE TODISASTERSUSAID responds to a range of emergencysituations that generally fall within the areasof natural disasters and complex emergencies.Natural Disasters are the consequences of anatural hazard and its effects on a populationand include events such as floods, earthquakes,tsunamis, storms, volcanic eruptions, anddroughts. Some disasters, however, are directlyor indirectly caused by humans such as chemicalspills, wild fires, crashes, and pandemics.Complex Emergencies, on the other hand, arelong-term man-made disasters that threaten thelives and livelihoods of populations, such as civilstrife, civil war, acts of terrorism, internationalwars, and industrial accidents.Office ofAssistanceU.S.ForeignDisasterUSAID responds to disasters through the Officeof U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA). Inthe event of a large-scale and urgent emergency,OFDA will deploy a Disaster AssistanceResponse Team (DART) to assist the U.S. Chiefof Mission and the USAID Mission. DARTs arecomprised of disaster specialists in the areas ofsearch and rescue, water and sanitation, food andnutrition, health, shelter, infrastructure, logistics,communications, and media. OFDA provideshumanitarian assistance for all types of naturaldisasters and complex emergencies. The rangeof disaster relief that OFDA can provide includesrelief commodities, services, transportationsupport, grants to relief organizations, and 2

technical assistance. In addition to emergencyassistance, OFDA supports disaster planning,mitigation, and local capacity building activitiesto reduce the impact of recurrent disasters.USG Response to DisastersThe United States Government (USG) hasestablished a procedure for responding tonatural disasters and complex emergencies thatincludes the steps outlined below. Differentfunding sources are available in different phases;understanding USG processes will avoid lookingto the wrong source for funding or otherresources.1. The US Ambassador declares a disasterif the scale of the disaster is beyond thecountry’s capacity to respond; the countryis willing to accept assistance and; it is in theinterest of the USG to provide assistance.2. OFDA uses the Disaster AssistanceAuthority to provide 50,000 to the USEmbassy or USAID to purchase reliefsupplies directly or through a NGO.3. OFDA may deploy staff to conductassessments, determine additional needs,and recommend relief supplies andproposals for funding.4. Depending on the scale of the disaster, theUSG may allocate funding via USAID budgetreallocation or through supplemental funding designated by the USCongress.5. USAID Missions and Bureaus develop procurement plans forreconstruction projects that are competed through Request forApplication/Proposals (RFAs/RFPs). 3

ALLIANCE MODELS INNATURAL DISASTERSAND COMPLEXEMERGENCIES: WHATWORKS?If you are designing a new partnership, a goodplace to begin is a review of what has alreadybeen successful in different phases of crisisresponse. In the following pages, several kindsof partnerships that have been used by USAIDand other organizations are highlighted.USAID typically organizes its response tonatural disasters and complex emergenciesaccording to five phases, each with distinctprimary activities.Alliances have beensuccessfully implemented in each of thesephases. Preparedness and Mitigation.Preparation involves developing plans tosave lives, minimize damage, and enhancecrisis response, while mitigation aims toreduce the probability of crises or reducetheir effects. This phase is more commonlyassociated with natural disasters, althoughnot exclusively. Acute Response. Involving immediateassistance to save lives, alleviate humansuffering, and reduce the social andeconomicimpactofhumanitarianemergencies, this phase is more commonlyassociated with natural disasters, althoughnot exclusively. 4

Recovery. In this phase, basic needs and livelihoods and theinfrastructure that supports them are restored. Recovery takes placeafter both natural disasters and man-made complex emergencies. Reconstruction. The reconstruction phase refers to efforts torebuild vital infrastructure destroyed or damaged by the disaster oremergency. Reconstruction is undertaken in the aftermath of bothnatural disasters and man-made complex emergencies. Transition. The transition phase of a crisis may fully or partiallyoverlap with the reconstruction phase. Whereas reconstructionfocuses on the rebuilding of physical assets, the transition phaseaddresses critical windows of opportunity to lay a foundation forlonger-term development, through such activities as promotingreconciliation, jumpstarting local economies, supporting nascentindependent media, and fostering peace and democracy. 5

MODEL 1: INVOLVE BUSINESS ASSOCIATIONSIN CRISIS PLANNINGIf the private sector is engaged in crisis planning before an emergencystrikes, these relationships can be crucial when needed in a responseeffort. A good way to reach multiple private sector actors is througha membership association. USAID, working with local officials, canmake the case for crisis planning, and often contributes funds, technicalassistance, guidance regarding local partner selection processes andhuman resource capacity.The Pan American Development Foundation (PADF)Disaster Management Alliance (DMA) was created to preparefor natural disasters. The DMA promotes the integration of the privatesector into disaster response, preparedness and mitigation, mainlythrough Chambers of Commerce and other associations. Activitiesinclude establishment of a disaster management and business continuitycommittee, leveraging corporate support for community disasterpreparedness training, developing emergency plans and practicingdrills, and risk reduction initiatives. Alliance members have successfullyresponded to a number of local emergencies.“Supporting evacuation drills,in coordination with disastermanagement authorities, is a primeexample of how companies can workwith the communities where theyoperate in the prevention of loss oflife and damage.”CHRISTINE HERRIDGEPAN AMERICAN DEVELOPMENTFOUNDATION 6 1

MODEL 2: CAPITALIZE ONCORPORATE/INSTITUTIONALCOMPETENCIESCorporations or other institutions with certaintypes of expertise can play a pivotal role inresponding to crises. For example, technology(mobile phones, two-way radios) can be criticalafter a natural disaster, and transportation andlogistics (moving key supplies and equipment)can save lives and minimize suffering. USAIDhas many ways to facilitate collaboration,including facilitating streamlined customs andtax protocols with host governments, advisingon the national/regional context, connectingassistance providers to existing programs inaffected areas and furnishing sector expertise.The CARE International and Motorolaglobal partnership provides a good example ofhow an ICT competency may be leveraged incrisis planning and response. Motorola donatescommunications products and services tocommunities isolated by natural disasters and/or recovering from civil strife.CARE’s staff help Motorola targetthis assistance to vulnerablecommunities. Another exampleis the range of alliances that theInternational Federationof Red Cross and RedCrescent Societies (IFRC)has established with Microsoftand Ericsson.Microsoft ishelping improve IFRC’s real-timecommunication during emergency2 7

“The CARE brand name is verymuch known in the local communityin Bangladesh. Our private sectorpartner needed that trust. Ourpartner had the technology. CAREneeded that. CARE alone could notprovide communications connectionsto the local community.”JAMIL AHMEDCARE BANGLADESHoperations while Ericsson is providing IFRC with telecommunicationproducts and services in exchange for training of Ericsson staff ondisasters and disaster management.Deutsche Post (DHL) and United Nations Office for theCoordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) havealso formed a global partnership to respond to emergencies. UNOCHAtrains DHL Disaster Response Teams in various aspects of crisisresponse and humanitarian assistance, and, when needed DHL sendsthose teams to manage airport logistics in the immediate aftermathof major disasters. TNT, the Dutch mail and logistics company,has invested more than 57 million in its “Moving the World”partnership with the United Nations World Food Programme(WFP). The partnership focuses on school feeding support, privatesector fundraising, emergency response, logistics, transparency andaccountability. A significant portion of TNT’s investment is employeetime and expertise in logistics including air freight, customs, warehousing,and ground transportation, which allows WFP to re-direct an equivalentamount of its budget to aid. 8

MODEL 3: INTEGRATECORPORATE DONATIONSMany multinational corporations and large national companies donateto emergency relief efforts for humanitarian reasons, especially in highprofile disasters that affect large populations. Some become involvedat the request of high-ranking officials such as the US president orleaders of the affected country and others. Where possible, USAIDleverages these resources with its own emergency funds to makeits acute response and recovery programs more effective. In suchinstances, USAID might contribute disaster funding, technical expertise,local partner selection advice, program oversight and coordination ofservices between corporate donors, the US military and internationaland local NGO partners.After the 2004 Asian tsunami, USAID forged 18 partnerships with theprivate sector in Indonesia and Sri Lanka that leveraged more than 17 million in private sector funds for reconstruction. In Indonesia,USAID formed partnerships with Unocal, ChevronTexaco,ConocoPhillips, Microsoft, and Mars that leveraged 14 millionof private sector cash resources. USAID matched dollar for dollar theresources provided by ChevronTexaco and Mars, and provided programoversight of the cash contributions.3 9

“After the 2006 Java earthquake, ConocoPhilips wantedto donate cash but required assurance that it wouldreally reach the target community. USAID saw a way tomeet the company’s needs by incorporating communityoversight activities from an existing USAID-funded,long-term education contract. We collaborated on apartnership for the reconstruction of school buildingsbased on a community-led process. USAID was ableto leverage 1 million in short-term disaster responsebecause of an existing USAID contract for longer-termdevelopment.”ELIZABETH SUNINDYOUSAID/INDONESIAIn Sri Lanka, USAID formed an alliancewith the American Jewish JointDistribution Committee and theBush Clinton Tsunami Fund toprovide playground equipment to 87 affectedcommunities. The Mission also formed astrategic alliance with Geneva Global, aninternational philanthropic advisory servicesprovider, to create a small grants program tofund local social development organizations,and leveraged nearly 3 million in additionalcash resources. USAID contributed matchingfunds, sector expertise and on-site humanresources from existing programs that advisedduring the beneficiary selection process.In the aftermath of the 2005 earthquakein Pakistan, world leaders appealed to theprivate sector for assistance. Immediately 10

“The Funddecided earlyon to allocateup to 5 millionto immediateearthquakerelief efforts andall remainingdonations tomid-to-long-termreconstruction.This was aconsciousdecision madepredominantlyto address thevaried needs ofthe disaster butalso to avoidany claims thatSAERF was‘holding ontomoney’.”following the quake, President Bush reachedout to five CEOs in the finance, chnology industries to help raise awarenessand funds for relief efforts. These CEOsestablished the South Asia EarthquakeRelief Fund (SAERF) and tappedthe Committee Encouraging CorporatePhilanthropy (CECP) to administer the funds.SAERF generated nearly 20 million thatwas granted to seven NGOs for immediaterelief as well as long-term reconstruction andrehabilitation. USAID technical staff playedpivotal roles in assisting CECP to assess NGOgrant proposals and make final awards.LESSONSLEARNEDSouth AsiaEarthquake ReliefFund 11

Corporate collaboration can also play a part in post-conflict recoveryand reconstruction efforts. In 2003, the Business HumanitarianForum (BHF), an association that encourages dialogue and mutualsupport between the business and humanitarian communities, and theUnited Nations Development Programme (UNDP) began apartnership to construct a pharmaceuticals factory in Afghanistan. BHFapproached the European Generic Medicines Association todonate manufacturing equipment, DHL to contribute transport andlogistics services and DEG, a German bank, for co-financing. The UNDPand BHF assessed and selected a local medical professional, who himselfinvested 35% of the funding for the project, as the local counterpart. TheSwiss Agency for Development and Cooperation providesoperational support to the alliance in Kabul.“Putting together these investmentprojects takes an enormous amountof work, but there is no other way toattract investment to post-conflictregions .We have developed a uniquemodel which builds on a philanthropicdonation by an established business,recruits interested local investors, makesuse of the credibility of an internationalorganization and the support of thelocal authorities.”JOHN J. MARESCABUSINESS HUMANITARIAN FORUM 12

MODEL 4: ENGAGEDIASPORA GROUPSWhen a crisis strikes, members of a country’sdiaspora are often among the first to mobilizea response. Diaspora groups and home townassociations send remittances to families,friends, and organizations to meet emergencyneeds. USAID works to establish partnershipswith diaspora groups in order to amplify thedevelopment impact of remittances and otherdiaspora resources.When Cyclone Sidr devastated thesouthwestern coast of Bangladesh inNovember 2007, twelve diaspora organizationsin the US, Canada and the UK came togetherto form the United Bangladesh Appealto raise funds. The group, led by Drishtipat, aUS-based diaspora non-profit organization,successfully raised over 300,000 to supportthe victims of the cyclone.4 13

“The Urban Institute (UI) asked USAID to send aconstruction expert to [Armenia]. By securing an expertin the field, UI hoped to convince other donors suchas the Lincy Foundation, an organization active inArmenian development, to join the developing project.The foundation had already committed 15 million fornew home construction, but .contributed another 30million.”EARTHQUAKE ZONE RECOVERY PROGRAMLEARNING STORY, USAID,Another example of an alliance involvingdiaspora members is the ArmenianEarthquake Zone Alliance. The alliancewas established three years after the 1988earthquake and focused on regional recoverythrough housing, market development anddemocratic reforms. A group of foundations(one of which is headed by an Armeniandiaspora member), organizations and USAIDcollaborated on a variety of activities. USAIDfacilitated the channeling of resources toproductive activities. For more information,see the case study at the end of this guide. 14

Diaspora members can also respond to man-made crises in theircountries of origin. For example, in 2006, USAID and the LebaneseAmerican Renaissance Partnership brought together successfulLebanese-American business, entrepreneurs and community leaders toassist municipalities and NGOs that needed resources to help Lebanesecitizens recover from conflict and rebuild infrastructure. A USAID staffmember currently heads LARP’s executive committee for current andfuture endeavors. 15

MODEL 5: BUILD ON LOCATION-SPECIFICCORPORATE INTERESTS5Sometimes corporations provide disasterrelief for business reasons that gobeyond philanthropy, such as repairing orreconstructing infrastructure that is criticalto their operations.In other instances,companies help communities where theiremployees reside, by repairing and rebuildinghomes, schools, health centers and othercommunity assets. Dynamic alliances thathave high impact can emerge from thesetypes of partnerships.In Sri Lanka, USAID formed partnerships withtwo key private sector actors to support the reconstruction of vocationaleducation centers destroyed in the 2004 tsunami. ChevronTexaco,whose subsidiary Caltex Lubricants Lanka had a local presence,workforce and product market, sponsored a vocational educationcenter dedicated to small engine repair. Thecompany donated 200,000 and providedtechnical training teams, its lubricant products,and jobs for graduates. The Joint ApparelAssociation Forum (JAAF) sponsoredtwo vocational education centers focused ontraining and graduating machine operators,pattern cutters, and mechanics for Sri Lanka’sgarment industry. JAAF provided coursecurriculum, industry standards, workshopdesign, training, and access to subsidizedequipment to the centers.JAAF alsoguaranteed jobs to graduates, which were inshort supply. 16

In several post-conflict situations, USAID has successfully implementedpartnerships that address livelihoods and enterprise development.Under this model, USAID may commit funding, material resources,technical expertise, training and/or advisory services. In Angola,ChevronTexaco, which had a local presence, and USAID each invested 10 million for post-conflict programs that helped ex-combatantsstart small businesses, established a private bank that lends to smalland medium sized enterprises, and provided agricultural extension andresearch services through NGOs.In Sierra Leone’s Kono Peace Diamond Alliance, USAID isworking with a range of diamond sector actors. The partnership’sfocus is to improve post-conflict working conditions and livelihoodsby bringing more diamonds to the legal market and securing a biggershare of profits for diamond diggers. At the Alliance’s launch, eachmember, including diamond giant DeBeers, committed to specificaction plans, including improving mining sector policies, establishing fairtrade diamond mining facilities, monitoring of legal and illegal diamonddealings, and public outreach and awareness. USAID provided technicalassistance and equipment to the Ministry of Natural Resources, accessto improved technology, economic and financial analysis of the diamondsector and organizational support. 17

This model can be used in complexemergencies when partners recognize thevalue of secure, stable and transparentoperating environments. One such successfulalliance is the Colombia Alliance forRestorative Justice, Coexistence,and Peace, which follows a model pioneeredin South Africa. The multiparty alliance isaimed at helping Colombia resolve its historyof domestic conflict and move towardspeace. The AlvarAlice Foundation,the Colombia Association of SugarProducers, and USAID invested nearly 3.4 million in the alliance, which works withyouth and farmers directly affected by conflict,and supports university-level coursework onhumanitarian law and restorative justice.“ Synergos organized a table discussion around theColombia Initiative for Restorative Justice and one of theinvitees was the Deputy Director of GDA.This meeting ledto the presentation of a detailed proposal to the Agencyand the procurement of a major grant to partially fundthe major components of the program .the Colombiainitiative’s director was able to use the GDA pledge tosuccessfully raise more than the match, through bothin-kind and financial contributions, from a broad array ofpartners .”DAVID WINDERSYNERGOS INSTITUTE 18

19

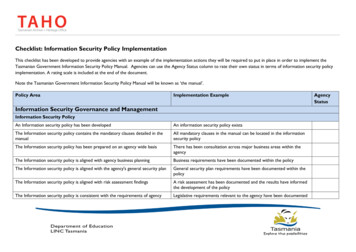

WHAT PRIVATE SECTOR INDUSTRIES MANATURAL DISASTERS AND MANType of CompanyCompany InterestInformation Technology/ TelecomMarket access, philanthropy, image,testing viability of products or marketapproaches in an emergency settingExtractivesLegitimacy/social license to operate,philanthropy, keeping employees andtheir families safe and healthyConsumer ProductsPhilanthropy, image, safety and securityof employees and families, repairingdamaged infrastructureTransportationPhilanthropy, image, employeesatisfaction, increased knowledge ofdisaster situationsHealth Care/ PharmaceuticalPhilanthropy, image, employeesatisfaction, market accessPrivate FoundationsPhilanthropy 20 NSoairdatawWLoProRpr

AY COLLABORATE IN RESPONDING TO-MADE COMPLEX EMERGENCIES?Non-Cash Resourcesoftware, computers, telephones,rtime, tracking systems, radios,a management, on-site technicalexpertiseIllustrative Partner CompaniesMicrosoft*, Cisco Systems*, Intel*, IBM, MotorolaEarthmoving equipment,warehousing, communicationsequipment, clinics and staffChevron Texaco, Unocal, Conoco Philips,Rio TintoWarehousing, products, localtransportationP&G, Unilever, Mars, Coca Colaogistics, transport, commoditytrackingUPS, DHL, FedExoducts, transportation, technicalteamsJohnson & Johnson, Pfizer, WyethResources available in existingrograms that can be channeledinto crisis responsesMellon, Gates, Ford, Prudential, JDC International 21

FINDING A GOODPARTNEROne of the first steps in identifying privatesector partners is to define the fit betweenunmet needs and opportunities, and theinterests and resources of the private sector.The following questions can help you identifythe fit between crisis resource requirementsand private sector interest, assets, andcompetencies.1What are the typical resourcerequirements in natural disastersand complex emergencies thatthe private sector can support?For each phase of a crisis, what resourcesare needed? Historically, what are theresource gaps or unmet needs? Whatresources do companies and privatefoundations have that they couldcontribute to crisis response?2What companies and privatefoundations have responded tonatural disasters and complexemergencies in the past? In whatphases of a natural disaster did theyparticipate? What resources did theyprovide and to what organizations didthey provide them? Talk to companiesthat are in sectors which are likelyto have their own well-developedemergency plans (oil, chemical, air and seatransportation, insurance). 22

3What multinational and large regional companieshave operations and/or customers in the country?Do these companies have crisis response policies and plans inplace? Do they manufacture products or have other assets orcompetencies locally that could be useful in natural disasters orcomplex emergencies? Do any of the companies and privatefoundations operating in the country have access to earmarkedcrisis response resources?4What areas of the country are prone to naturaldisasters or complex emergencies? What companies haveoperations and business interests in areas that are prone to naturaldisasters or that are near conflict zones? What companies havemanufacturing facilities, markets, or draw employees from theseareas?“One should always look for thebenefit of a collaboration and focuson things each partner can do best.USAID’s certificate program in postearthquake Armenia was unique.Using Housing Certificates hasmade this alliance successful for all.”STEVE ANLIANURBAN INSTITUTE 23

OTHER RESOURCES TO HELPIDENTIFY PRIVATE SECTORPARTNERSBelow is a list of additional resources that can help you think aboutalliances and identify private sector partners. Links are available on theGDA website. International Center for Disaster Information – CIDIis supported by USAID’s Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, andprovides guidance to international corporations (and others) onappropriate disaster donations. American Chambers of Commerce – Most Amchamchapter websites will have a list of chapter resources as well asa section containing a list of chapter members that USAID cancontact about possible partnerships. US Chamber of Commerce, Business CivicLeadership Center – The Chamber of Commerce websitecontains publications on disaster response, lessons learned andrecommendations for future interventions from a public-privateperspective. Business Humanitarian Forum – The BHF website containsarticles, speeches and other information about how to form publicprivate partnerships. Committee Encouraging Corporate Philanthropy– The CECP website is aimed at corporations that are alreadypredisposed towards giving. It contains membership lists,publications, case studies and other resources for public-privatepartnering. USAID Regional Alliance Builders – The GDA websitehas a list of USAID contacts who can help you with partnershipformulation, whether by sector (agriculture, health, humanitarianassistance, etc.) or by geographic region. 24

Department of CommerceForeign Commercial Service– The Foreign Commercial Servicehas a corporate partnership programthat seeks to expand the US exportbase through innovative public-privatepartnerships. The website contains listsof partners by product/service sector. Business Roundtable – BusinessRoundtable’s Partnership for DisasterResponse has mobilized millions ofprivate sector dollars in assistance tovictims of natural disasters aroundthe world in partnership with the USgovernment and non-governmentalagencies. The website containsinformation on this initiative as well ascontact information. Disaster Resource Network, aninitiative of the World EconomicForum – The DRN’s website containsinformation on how to develop publicprivate partnerships for humanitarianrelief. The DRN’s HumanitarianResponse Initiative, which is partneredwith the UN’s Office of Coordinationfor Humanitarian Affairs, also focuses onmatching private sector resources withhumanitarian needs in advance of crises. The National Council for Public-Private Partnerships– NCPPP defines and demonstrates how public-privatepartnerships work, offering issue papers, case studies, a speakersbureau and other resources for those interested in designingpublic-private partnerships across a range of sectors. 25

WHAT PARTNERS CAN OFFERThe private sector can add value to alliances in many ways. Considerthe following list of resource requirements, listed by disaster phase. Inaddition to cash, could private sector actors contribute any of theseitems? Preparedness/Mitigation- Warning systems- Emergency communications- Evacuation plans- Improved building codes- Retrofitting of lifeline buildings- Seismic monitoring systems- Improved community infrastructure Acute Response*- Medical services- Food- Water- Sanitation- Transportation- Temporary shelter- Settlement camps- Communications*USAID encourages cash donations because they allow aid professionals to procureth

established a procedure for responding to natural disasters and complex emergencies that includes the steps outlined below. Different funding sources are available in different phases; understanding USG processes will avoid looking to the wrong source for funding or other resources. 1.