Transcription

WoodWiseFOREST FLORAWoodland Conservation News Spring 2018QUESTIONINGANCIENTWOODLANDINDICATORSSURVEYING& RESTORINGWOODLANDFLORATIME FORA BUNCEWOODLANDRESURVEYWOODLANDFLORAFOLKLORE& REMEDIES

WTML / Georgina SmithCONTENTS3481116202224Introduction3 Introduction4 Questioning ancient woodland indicators8 Trouble for bluebells?11 The world beneath your feet16 T ime for a Bunce resurvey20 Wild plants of the Cairngorms22 Woodland flora folklore and remedies24 Tree health update25 Woodland Trust research updateEditors: Kay Haw and Karen HornigoldContributors: Julia Webb, Anne Goodenough, Deborah Kohn, AlastairHotchkiss, Simon Smart, Sian Atkinson, Robert Bunce,Claire Wood, Gwenda Diack, Kay Haw, Matt Elliot andChristine Tansey.Designer: Emma Jolly and Rebecca Allsopp25ailinge by emrg.ukSubscrib odlandtrust.ooweveration@e and nfassilconservaouur dete way ykeep yoange th t emailhcnWe willac. You– jussell them us at any time st.org.ukmtond ruhear frwoodla 3300.@sretr3suppo330 33or call 0Spring is probably the best time to appreciate woodlandground flora. The warming temperatures encourageshoots to burst from bulbs, breaking through the soilto reach the sunlight not yet blocked out by leaves thatwill soon fill the tree canopy. Their flowers bring colourto break the stark winter and inspire hope in many thatsee them.The species of flora covered in this issue are vascularplants found on the woodland floor layer. Vascular plantshave specialised tissues within their form that carrywater and nutrients around their stems, leaves and otherstructures, which allow them to grow taller than nonvascular plants.In the UK, species found on the woodland floor includebluebells, Hyacinthoides non-scripta, yellow archangel,Lamiastrum galeobdolon, and early purple orchid, Orchismascula. They rely on the early lack of leaves or opennessof the canopy to allow sunlight to reach them. They cannotprosper in dense shade and die off as tree leaves burst andexpand to capture the light.In this editionCertain vascular plants have been used as indicators toassess the ancient status of woods in the UK, to supporthistorical map data and other written records. Researchersfrom the University of Gloucestershire discuss recent workthat has called this system into question.The issue of bluebell hybridisation and complexities overthe classification of natives and non-natives is covered byscientist Deborah Kohn, whose research has informed theWoodland Trust’s own work.The Woodland Trust’s Alastair Hotchkiss focuses on therestoration of plantations on ancient woodland sites.Gradual thinning and natural regeneration of native treescan allow sunlight to reach the soil again and enable thereturn of wildflowers surviving in the seed bank.The Woodland Survey of Great Britain 1971-2001recorded a change and loss in broadleaf woodlandground flora species. The driver was thought to be areduction in the use and management of woods. Thisfinding encouraged an increase in management. Severalexperts involved look at this and the potential for a futureresurvey to analyse the current situation.Many initiatives strive to protect rare, native pinewoodspecies. Cairngorms Wild Plants Project Officer GwendaDiack shares some of the work being undertaken in theUK’s biggest national park.The Woodland Trust’s Kay Haw reflects on the folkloreand medicinal properties inspired through the centuriesby the beauty and power of woodland flora.This edition also has two new sections. The first is atree health update, as pests and pathogens are seriousand immediate threats to the UK’s trees and woods.Read about current issues and simple actions youcan take to help. There is also an update on three PhDprojects supported by the Woodland Trust’s evolvingresearch programme; covering soils, ancient trees andsocial wellbeing.Please note: external articles do not necessarily reflect theviews of the Woodland Trust.Cover photo: Deborah Kohn2Wood Wise Woodland Conservation News Spring 2018Wood Wise Woodland Conservation News Spring 2018 3

Anne GoodenoughQuestioning ancient woodlandindicatorsJulia C. Webb & Anne E. GoodenoughAncient woodland indicatorsThe vascular plant species most commonly associatedwith ancient woods are now regarded as ancient woodlandindicators (AWIs). Within the UK, there are many differentAWI lists depending on the floristic conditions of specificregions or counties. Other countries, including many inmainland Europe and the USA, have adopted similarsystems based on their own native flora.All AWIs have a tendency to be intolerant of non-woodlandlocations, often being shade-loving. They are unable towithstand disturbance, perhaps due to a shallow root base,and are slow to colonise new areas, sometimes by virtueof limited seed dispersal distance. So the presence of suchspecies at a specific site should be indicative of that woodbeing old and undisturbed (ancient) rather than recent,disturbed or interrupted.However, surprisingly, many AWIs are much more resilientto woodland interruptions or clearance than previouslythought. Is it time to rethink the use of AWIs to classifyASNW?The current AWI systemIn England and Wales, ASNW is classed as an area thathas been continually wooded since 1600AD. It is 1750AD inScotland, due to the oldest, most reliable maps. However,some historical maps do not extend far enough back (withclarity) in most cases, so it can be difficult to prove theancientness of a woodland. This has resulted in the AWIapproach becoming so valuable and common. As it is rareto find good historical maps for multiple ASNW areas, ithas proven difficult until now to test or validate the AWIsystem itself.A novel way to assess the age of specific woods withoutusing AWIs is to use fossilised pollen from woodland soilprofiles in combination with radiocarbon dating. Analysisof fossilised pollen to reconstruct past environments is wellestablished in open habitats, such as meres and wetlands,lake sediments and ice cores.However, it has rarely been used in woodland habitats, asonly very localised vegetation tends to be represented inthe pollen incorporated in the sediments of forest hollowsor wet ditches. Soil profiles from these sheltered locationsreflect local vegetation rather than the regional pollensignal. This makes them ideal for assessing changingspecies over time in that specific, developing wood, orchanges generated through humans. Woodland age andcontinuity can be ascertained by considering the speciesrepresented and their arboreal or non-arboreal status inrelation to radiocarbon dating, which provides a methodfor establishing the age of the changes recorded in thepollen sequence.Julia WebbFor years, the presence of certain vascular plants hasbeen used to help classify woodland as ancient, but newresearch calls this method into question.The identification and recognition of certain woodlandas ‘ancient’ is vital. All woods can be valuable from abiodiversity perspective, but ancient semi-natural woodland(ASNW) is often especially important for supporting rareor declining species – such as herb Paris, Paris quadrifolia,wild daffodil, Narcissus pseudonarcissus ssp pseudonarcissus,and lesser skullcap, Scutellaria minor. Yet they are oftenhighly fragmented and vulnerable. So the classificationof woodland as ancient is an important step in informingconservation legislation, planning and land use policies.In the late 19th century, botanist Francis Buchanan Whitenoted that the oldest pine forests of Scotland supporteda range of plant species that were much less common inyounger woodland or woodland that had been disturbed.He particularly highlighted twinflower, Linnaea borealis,creeping lady’s-tresses, Goodyera repens, and one-floweredwintergreen, Moneses uniflora, as being species that seemedto be associated with older, more established, woodland.Despite this, it was not until the 1970s that GeorgePeterken created a list of species commonly found in ASNWand the UK started to define ASNW based on the presenceof particular species.Small leaved lime pollen under a microscope (0.045mm in diameter).4Wood Wise Woodland Conservation News Spring 2018Wood Wise Woodland Conservation News Autumn 2018 5Ancient oak woodland

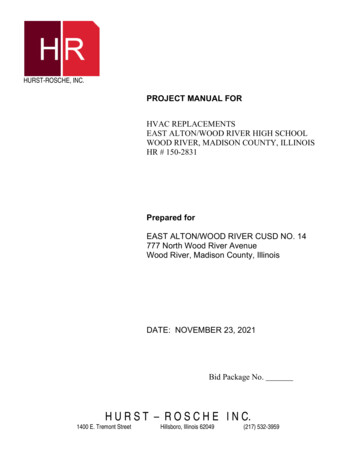

Testing the AWI systemOf the nine sites studied, analysis of pollen revealed justtwo had been continuously wooded and four of the siteshad interruptions to woodland continuity. The remainingthree were not currently wooded and the pollen recordrevealed these sites had not been recently, as had generallybeen assumed. Remarkably, all nine sites currently have 12or more AWIs present, including those that have not beenwooded for over 2,000 years.The study shows that AWIs can not only be extremelyresilient to interruptions in woodland continuity, they canalso persist for a very long time – approximately 2,800years in the case of Skomer Island. This highlights theneed to review, modify or reimagine our current system fordefining and classifying ASNW in the UK.In a recent study , nine wooded or previously wooded siteswere selected to test the AWI system. These sites haddetailed pollen profiles and associated radiocarbon datesto allow detailed and objective inferences to be madein their woodland history. The sites were also surveyedfor their current flora, particularly those woodlandunderstorey plants that feature on Peterken’s andRackham’s AWI lists.Finding a single AWI species in a woodland does notautomatically classify it as ASNW; a number of AWIs needto be present before the site is designated. The requisitenumber of species varies in different counties; sometimes itis as low as five, such as in Bedfordshire. More commonly,12-20 AWI species need to be identified before a woodobtains ASNW status.123Proven continuouswoodlandDerrycunihyWoodSouthern IrelandWistman’s2834WoodDevonWoodland interrupted in last 2000 yearsNot currently woodland(last evidence for woodland c.2,500 years ago)Garbutt WoodNorthumberlandSydlings CopseOxfordshirePiles CopseDevonJohnny Sheltand IslandsSkomer IslandPembrokeshire72751246212074Next stepsUsing pollen analysis to establish the age of woodland andits continuity may be a useful way to classify ASNW, butthis approach is not without considerable time and effort.It is unlikely that pollen analysis will become routine inassessing ancient status due to cost and time, especiallygiven that, as with many techniques that use indicators,one of the benefits of the current AWI system is the speedwith which assessments can be carried out.One possible way forward would be to develop AWI listsfurther. In the early 2000s, Rackham denoted a subset ofAWIs as being strictly or strongly associated with ASNW.A numerical system could be introduced so particularspecies, such as greater stitchwort, Stellaria holostea, andvalerian, Valeriana officinalis, which were never found oncleared sites, could have a higher weighting. AWI speciessuch as ramsons, Allium ursinum, opposite-leaved goldensaxifrage, Chrysosplenium oppositifolium, and bluebells,Hyacinthoides non-scripta, would have a lower weighting,as they can be important but can often be found in nonwoodland settings too.Consideration might also be given to defining or redefiningthe minimum number of species needed for a site to beregarded as ASNW. This could be a relative threshold, bysite size, or percentage of total number of species present,or by incorporating species into a system that are ‘reverseindicators’ of ancientness – those species very tolerant3of disturbance and often found in young woods, such asfoxglove, Digitalis purpurea.Another way to strengthen the usability of the AWI systemwould be to incorporate other organisms (taxa) into it.This may mean that lichens, fungi and beetles, whichhave previously been used in isolation as AWIs, could beincorporated into a super-system that might give thegreatest precision when classifying woodland.Fundamentally, the aim of conservationists usingwoodland indicator species is to preserve ASNW forits unique biodiversity. This new research does not aimto prevent ASNW being classified, but it does seek toencourage practitioners to adopt new classificationsystems to further promote the success of these rich anddiverse environments.Professor Anne Goodenough is Professor of Applied Ecologyat the University of Gloucestershire.Julia Webb is Senior Lecturer and Course Leader of theBiosciences programmes at University of Gloucestershire.1. Webb, J.C and Goodenough, A.E. 2018. Questioning the reliability of“ancient” woodland indicators: Resilience to interruptions and persistencefollowing deforestation. Ecological Indicators, 84 354 – 363.2. Peterken, G.F., 1974. A method of assessing woodland flora forconservation using indicator species. Biological Conservation, 6, 239-245.3. Rackham, O., 2003. Ancient woodland: Its history, vegetation and uses inEngland (revised edition). Castlepoint Press, Dumfries.Anne GoodenoughTable 1. Locations and outcomes of woodland history studies, along with the number of ancient woodland indicator speciespresent at those sites.6Wood Wise Woodland Conservation News Spring 2018Lesser celandine and wood anemone are both AWI speciesWood Wise Woodland Conservation News Spring 2018 7

D. Kohn / RBGETrouble for bluebells?Rising concernD. Kohn / RBGEThe idea that our bluebells might have a problem seems tohave started around 1973, when a brief note suggestingthat ‘Spanish’ and hybrid bluebells were under-recordedappeared in the May newsletter of the BotanicalSociety of the British Isles (BSBI). Attention to this ideaheightened in 1987 with a succinct and influential letterto the BSBI newsletter, asserting that garden bluebellsconsisted mainly of hybrids between the British andSpanish bluebell species.By 2001, people like Germaine Greer were making a standfor native bluebells in the national press, pointing out thatcommercial bulbs were more likely to be ‘Spanish’ thanEnglish despite their labelling. Articles followed trumpetingthe ‘death knell’ of the English bluebell, and alarm grewwith awareness. The general sense was that what damagethe sturdier, more vigorous ‘Spanish invader’ did not wreakdirectly on the gentle native by muscling it out of itstraditional habitats, cross-pollination would finish off.It was not difficult to see where the concern was comingfrom. Knowledgeable people were reporting new prevalenceof garden-type bluebells, including amongst natives inbroadleaf woodland, the beloved native bluebell’s mostsecure stronghold. Plantlife published the results of itsvolunteer survey and the alarming observation that onequarter of the 4,500 records amassed, which could beanything from a smattering to a vast woodland carpet,were not entirely native.It also reported that 16% of all submitted recordsassociated with broadleaf woodland habitat were Spanishor mixtures of Spanish and native bluebells. UK distributionmaps show coast-to-coast presence attributed to bothH. hispanica and the English-Spanish hybrid, known asH. x massartiana, within the 10km2 sampling unit.A non-native showing upright habit, short flowers, but curly flower tips andwhite pollen8Wood Wise Woodland Conservation News Spring 2018D. Kohn / RBGEUntil a couple of decades ago, to walk in a bluebell woodwas simply to be immersed in one of spring’s greatestdelights and enjoy one of nature’s most extraordinaryscenes. These days our appreciation might be taintedby a hint of uncertainty – are these all native bluebells?The native British or English bluebell, Hyacinthoides nonscripta, has a range that extends from the UK into northernEurope (France, Netherlands, Belgium) and south along theAtlantic coast into northwestern Spain. There it meets,and is replaced by, a sister species, H. hispanica, thatranges through the western part of the Iberian Peninsula inSpain and Portugal.These two species are closely related and in the past havebeen considered either to be subspecies of a single species,or H. hispanica a subspecies of H. non-scripta. H. hispanicawas introduced into Britain in the late 1600s as anornamental plant. The first UK hybrid between the BritishH. non-scripta and the Iberian H. hispanica was recorded inthe wild in 1963. But the presence and particular look ofa garden escape were not of great interest to recorders ofwildflowers until relatively recently.D. Kohn / RBGEDeborah KohnWhite non-nativesQuantifying the threatThe Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) and Centrefor Ecology and Hydrology (CEH) began investigating thethreat to natives posed by non-native introduced bluebellsin 2004. The Natural History Museum London was alreadyinvolved in an analysis of relationships among speciesin the genus Hyacinthoides from the UK to the westernMediterranean and North Africa.To understand what was happening with our native, wefirst needed a detailed account of how bluebells weredistributed in the UK landscape: a snapshot that wouldguide inferences about habitat preferences of the differenttypes, and perhaps suggest the processes behind theapparently rapid spread of non-natives. We needed toquantify their current prevalence in order to understandwhat the future might hold.We began to collect data on bluebells in the field, lookingfor the distinctive features of H. non-scripta and H. hispanicato identify flowers as native, non-native or hybrids. Ourfirst surprise was that instead of finding H. non-scripta andH. hispanica and an intermediate between them, we found acontinuum of flower and plant shapes from typical nativesto distinctly not native.The specific characteristics of native plants (tubularflowers, drooping flower head and white pollen) andcharacteristics supposedly diagnostic of non-natives(blue pollen and no scent) did not hold up. Pollen colourwas overwhelmingly white or cream, not blue (75% of allbluebells examined, including over 50% of non-natives) andmost flowers (59%) had some sweet scent, while 33% ofnatives and 48% of non-natives seemed to have none.White nativeOther characteristics turned out to be matters of degree.Flowers ranged from tubular to bell-shaped, with tips fromtightly curled to relaxed, and leaf widths from narrow( 1 cm) to broad (2 cm) in smooth continua. Furthermore,the distinguishing characteristics were jumbled, notclustered into distinct types. We saw native flowersarranged on all sides of upright stems or with ultra-wideleaves, and shorter, more bell-shaped flowers with creamypollen on drooping stems.In a final twist, we noticed flower characteristics changingover time, the inflorescences becoming upright and flowerswider as fruit developed. We found few examples of plantsthat could conclusively be assigned to the species H. hispanica.An upright native in WalesWood Wise Woodland Conservation News Spring 2018 9

D. Kohn / RBGED. Kohn / RBGED. Kohn / RBGEThe world beneath your feet:the role of ground flora in the restoration of ancient woodland sites.Subtly non-nativeEarly conclusionsWe did learn that natives are far more abundant than nonnatives, but at a random point on the map you are slightlymore likely to encounter non-natives than natives. Thisis because the non-natives are more evenly distributedin small groups throughout the landscape and moreabundant in built habitat defined by human activities,while natives concentrate their great numbers in a fewmore preferred habitat types. Theoretically, these smallclusters of non-natives have the ability to spread pollento natives within distances that their pollinators can fly,usually taken to be 1-3km.White and pink natives are rare and petals can be stripedwhere frost has nipped a closed bud. Natives are morecommon and dense in the warmer, wetter west of theUK (at least in Scotland) than the drier, colder eastwhere non-natives are more common. However, the widedistribution of natives across the UK attests to boththe suitability of the UK’s climate generally and to theircolonisation of all suitable habitats over the 10,000 yearssince the last glaciation. The non-native bluebells have hadcomparatively little time, just over 300 years, to adapt andfind their way around the UK.What do we make then of earlier records showingroughly equal representation of H. hispanica and theH. x massartiana hybrid across the UK? Was it H. hispanicathat jumped (or was pushed) over the garden wall andestablished itself through the landscape, hybridising withnatives as it went? That could be part of the story, andthere may be H. hispanica individuals still out there beyondour surveyed areas in south-central Scotland.We can be sure that commercially developed varieties, notH. hispanica but hybrids, were planted by bluebell-lovinggardeners. Dozens of bluebell varieties called ‘Spanish’or ‘H. hispanica’, and fewer called ‘H. non-scripta’, werecommercially available for decades. The ‘Spanish’ varietiesappealed for their range of colours, height and manyflowers, and are still in evidence. These garden types werealso discarded, composted and guerilla-introduced intowoodlands and riverbanks, often in the mistaken beliefthat they were native bluebell start-ups.This casual naming of cultivars is the source of the ideathat the non-native bluebells increasingly seen outsidegardens were H. hispanica. Common names can confuse– the name ‘bluebells’ itself refers to different speciesin different places. While ‘Spanish’ used to serve asthe common name for H. hispanica, the UK non-nativelooks very different from H. hispanica. If we do call them10Stripey native‘Spanish’, we should be careful to distinguish between thesenaturalised plants and the species that was probably one oftheir ancestors.Future workIt has proved a slow process to study bluebells, and someof our initial approaches needed swift revision. Individualplants cannot be tagged and followed over consecutiveyears, because the whole above-ground plant disappearsfrom September to February. Flowers are essential foridentification, restricting survey work to a few weeks ofthe year during the bloom. And spread of existing groups isfar from rapid – a survey of H. non-scripta transplanted 45years earlier into woodland in Belgium showed that in the41% of populations that survived, the expansion rate fromthe point of introduction was no more than 0.06 metresper year.Finding identification tricky pushed our research in newdirections. Experimental pollen transfer between plantswill tell us whether hybridisation is really as ready and bidirectional as has been assumed. Monitoring over severalyears how natives and non-natives live, grow and reproducein common gardens in a range of climate zones will give usan idea whether the non-natives really are more vigorous,and whether changing rainfall or temperatures couldinfluence competitiveness for the better or worse of thenative species.Molecular methods will refine our understanding of whatmakes a native (besides its fleeting appearance), revealwhere in the H. hispanica range the Spanish element inUK bluebells comes from, and show whether and wherenon-native DNA has infiltrated native populations. As withall good research questions, the more we learn the morequestions arise. The work goes on, as do - we hope - ournative bluebells.Dr Deborah Kohn is a research associate at Royal BotanicGarden Edinburgh and recipient of a Daphne JacksonFellowship funded by the Natural Environment ResearchCouncil 2004-2007.Alastair HotchkissAround 50% of the UK’s ancient woodland has beendamaged, having been cleared and replanted with densenon-native conifers and broadleaves. Restoration of these‘plantations on ancient woodland sites’ (PAWS) is possible,and a rich diverse woodland flora can thrive again.Whilst non-native plantations on ancient woodland siteslack the canopy of trees found in native ancient seminatural woodland, they usually still contain remnants ofancient woodland specialist plants that are clinging on inthe darkness. Time is of the essence to restore these sitesbefore these features are lost forever.Without pre-plantation survey data, it is difficult to saywith any confidence what was in existence prior to theplantation. However, clues do persist and these are referredto as remnant features. They provide an unbroken linkback to what stood before and act as the foundation forrestoration management. Woodland specialist plants(or ancient woodland indicator species) may still survivein plantations on ancient woodland sites and are easyto identify; thus they are used as part of the WoodlandTrust’s PAWS assessment process.‘Hotspots’ or concentrations of remnant ancient woodlandspecialist plants are mapped and identified as featuresin need of management to enhance them, such as whenheavily shaded by plantation trees or invasive species.They are also identified to avoid damage and destructionduring harvesting operations, being smothered in brash,track construction or impacted by compaction.Woodland specialist plantsThe ground flora of our woodland varies greatly across theUK, determined by underlying geology, soil types and landuse history among other factors. Plants help to distinguishand characterise the regional distinctiveness of our ancientwoodlands, from the oxlip, Primula elatior, woodlandsof East Anglia, to the twinflower, Linnaea borealis, ofCaledonian pinewoods, and all the assortments of differentplants which combine into locally distinctive communities.This regional and local variation is an importantconsideration in assessing PAWS. Some indicator speciescan tolerate the shady conditions in conifer plantations, forexample wood sorrel, Oxalis acetosella, is often abundantin dark Sitka spruce plantations, and may actually betaking advantage of these situations. There is greatvariation from species that tolerate deep shade to thosethat flourish in dappled sunlight or exposure to the fullsun. Not all ancient woodland would naturally have a richground flora. Some ancient beech woods have a very poorground flora, but have a richness of fungal and insect lifeassociated with the trees themselves, especially when theyare dead or decaying.Alastair HotchkissNative with some confusing characteristicsChicken, E. 1973. BSBI News, Vol 2 No 2, Letter to the Editor, page 38.Grundmann, M. et al. 2010. Phylogeny and taxonomy of the bluebell genusHyacinthoides, Asparagaceae [Hyacinthaceae]. Taxon 59, 68–82.Kohn, DD et al. 2009. Are native bluebells (Hyacinthoides non-scripta) at riskfrom alien congenerics? Evidence from distributions and co-occurrence inScotland. Biological Conservation 142, 61-74.Page, KW 1987. Hybrid Bluebells. BSBI News 46, page 9.Pilgrim, E. & Hutchinson, N. 2004. Bluebells for Britain. Plantlife.Van der Veken, S. et al. 2007. Over the (range) edge: a 45-year transplantexperiment with the perennial forest herb Hyacinthoides non-scripta. Journalof Ecology 95, 343-351.Wood Wise Woodland Conservation News Spring 2018Wood Wise Woodland Conservation News Spring 2018 11Rich ground flora of ancient woodland specialists

Paul Glendell12Wood Wise Woodland Conservation News Spring 2018Clanger Wood showing plantation and ancient woodlandWood Wise Woodland Conservation News Autumn 2018 13

Alastair HotchkissAlastair HotchkissLaura ShewringCritical Streamside with tutsan, marsh hawks beard,sanicle, scaly male fern, garlic, ash, wych elm and rowanGround flora hotspot in PAWS with bluebell and archangel where light reachesShady beech, Fagus sylvatica, woods have their ownspecialist plants such as yellow birds-nest, Monotropahypopitys, and the similar sounding birds-nest orchid,Neottia nidus-avis - a saprophyte, meaning it lives ondead or decaying organic matter, in the deep humus ofdensely shaded Fagus woods on chalky soils. The criticallyendangered ghost orchid, Epipogium aphyllum, is anothersaprophytic herb which grows in deep leaf-litter in Faguswoods on chalk, with little or no associated ground flora.However, outside the range of ancient native beech woods,the shade and leaf litter from dense beech PAWS cancreate unfavourable conditions for the remnant nativeancient woodland ground vegetation.Another contrast to the classic spring flower woodland ofthe lowlands is our more acidic woodland on poorer soilsor upland regions. For example, our oceanic oakwoodscan sometimes be a lush carpet of mosses and liverworts(bryophytes), with greater fork-moss, Dicranum majus, littleshaggy-moss, Rhytidiadelphus loreus, greater whipwort,Bazzania trilobata, and a whole host of scarce and rarespecies associated with these humid woods. Some otherancient woods can be dominated by grasses or ferns, suchas birch woods dominated by wavy hair-grass, Deschampsiaflexuosa, or bracken, Pteridium aquilinum, in some of our oakand beech woodland on more acidic brown soils.Understanding remnant features as proxiesAncient woodland ground flora supports a much widerhost of ancient woodland specialist species. For example,patches of wild garlic, Allium ursinum, can support the wildgarlic hoverfly, Portevinia maculata, whose larvae developonly in the bulbs and stem-bases of this plant. The drablooper, Minoa murinata, is one of our few day-flying mothsand depends on populations of its food plant wood-spurge,14Wood Wise Woodland Conservation News Spring 2018Wild garlic hoverfly Portevinia maculataInstead they formed a closed novel bryophyte-dominatedEuphorbia amygdaloides. These are just two examples fromcommunity, containing few of the typical oak woodlandthe thousands of plant-insect interactions. Pre-plantationvascular plantsand relic native broadleaves could retain old woodlandlichens like the barnacle lichen, Thelotrema lepadinum, andAncient woodland restorationoak stumps or pre-plantation lying oak deadwood couldAlthough it varies between species, many of our nativesupport numerous saproxylic invertebrates associatedwoodland plants need a certain level of light. The dappledwith decaying wood.sunlight that filters through a canopy of broadleaved treesThe ancient woodland soi

4 Wood Wise Woodland Conservation News Spring 2018 Wood Wise Woodland Conservation News Autumn 2018 5 Questioning ancient woodland indicators Julia C. Webb & Anne E. Goodenough For years, the presence of certain vascular plants has been used to help classify woodland as ancient, but new research calls this method into question.