Transcription

NURTURING CAREFOR EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENTA F RAME WORK FOR HE LP ING CHILDR EN SU RVI VE A NDTH RIVE TO TRAN SFORM HEA LTH A ND HUM A N P OTENTIA LIN SUPPORT OF

NURTURING CAREFOR EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENTA F RAME WORK FOR HE LP ING CHILDR EN SU RVI VE A NDTH RIVE TO TRAN SFORM HEA LTH A ND HUM A N P OTENTIA LIN SUPPORT OF

Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transformhealth and human potentialISBN 978-92-4-151406-4 World Health Organization 2018Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; igo).Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes,provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestionthat WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If youadapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If youcreate a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “Thistranslation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content oraccuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”.Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediationrules of the World Intellectual Property Organization.Suggested citation. World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, World Bank Group. Nurturing carefor early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and humanpotential. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris.Sales, rights and licensing. To purchase WHO publications, see http://apps.who.int/bookorders. To submit requestsfor commercial use and queries on rights and licensing, see http://www.who.int/about/licensing.Third-party materials. If you wish to reuse material from this work that is attributed to a third party, such as tables,figures or images, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that reuse and to obtainpermission from the copyright holder. The risk of claims resulting from infringement of any third-party-ownedcomponent in the work rests solely with the user.General disclaimers. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not implythe expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory,city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lineson maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsedor recommended by WHO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissionsexcepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.All reasonable precautions have been taken by WHO to verify the information contained in this publication.However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. Theresponsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall WHO be liable fordamages arising from its use.Design and layout: Blossom; Sara Naicker.Printed in Switzerland

Table of contents1Foreword01Introduction2A framework for nurturing care4Why this Framework now?4What contribution can this Framework make?4The audience04Five strategic actions28Strategic action 1Lead and invest29Strategic action 2Focus on families andtheir communities30Strategic action 3Strengthen services31Strategic action 4Monitor progress32Strategic action 5Use data and innovate05Making nurturing care happen36Roles and responsibilities37The health and nutrition sector02A case for nurturing care5We know why early childhood development is important9We know what threatens early childhood development38The education sector10We know that very large numbers of children are at riskof poor development40The social- and child-protection sectors42Committing to action and milestones12We know that young children need nurturing care todevelop to their full potential44Additional resources17We know how to support families and caregivers inproviding nurturing care22Reaching all caregivers and children to meet their needs03The time to act is now24Vision25Targets26Guiding principlesAnnexes47Annex 1. Glossary48Annex 2. Proposed indicators50References54Acknowledgementsiii

ivREPORT 2018

ForewordWhat is one of the best ways a country can boostshared prosperity, promote inclusive economicgrowth, expand equitable opportunity, and endextreme poverty? The answer is simple: Invest inearly childhood development.Investing in early childhood development isgood for everyone – governments, businesses,communities, parents and caregivers, and mostof all, babies and young children. It is also theright thing to do, helping every child realizethe right to survive and thrive. And investingin ECD is cost effective: For every 1 spent onearly childhood development interventions, thereturn on investment can be as high as 13. Earlychildhood development is also key to upholdingthe right of every child to survive and thrive.We now understand that the period frompregnancy to age 3 is the most critical, when thebrain grows faster than at any other time; 80% ofa baby’s brain is formed by this age. For healthybrain development in these years, children needa safe, secure and loving environment, with theright nutrition and stimulation from their parents orcaregivers. This is a window of opportunity to lay afoundation of health and wellbeing whose benefitslast a lifetime – and carry into the next generation.middle-income countries – or more than fourin every ten – risk missing critical developmentmilestones due to poverty or stunting.The new Nurturing Care Framework drawson state-of-the-art evidence on how earlychildhood development unfolds to set out themost effective policies and services that willhelp parents and caregivers provide nurturingcare for babies. It is designed to serve asa roadmap for action, helping mobilise acoalition of parents and caregivers, nationalgovernments, civil society groups, academics,the United Nations, the private sector,educational institutions and service providers toensure that every baby gets the best start in life.The Framework builds on the foundation ofuniversal health coverage, with primary care at itscore, as essential for all sustainable growth anddevelopment. It articulates the important role thatall sectors, including the health sector, must playto support the healthy development of all childrento develop optimally and reap maximum benefitfrom pre-school and formal education.Meanwhile, the cost of inaction is high. Childrenwho do not have the benefit of nurturing care intheir earliest years are more likely to encounterlearning difficulties in school, in turn reducingtheir future earnings and impacting the wellbeingand prosperity of their families and societies.Current estimates are that nearly 250 millionchildren aged under five years in low- andAs we work together to realize the vision ofthe 2030 Goals to leave no one behind, wemust act urgently now to make investing inearly childhood development a priority in everycountry, every community and every family. Onbehalf of our organizations, we commit to bepart of the movement to create an inclusive andsustainable world, starting with investment inthe earliest years – to realize the right of eachand every child to survive and thrive, to build amore sustainable future for all.Henrietta H. ForeExecutive DirectorUNICEFTedros Adhanom GhebreyesusDirector-GeneralWorld Health OrganizationAnnette DixonVice President, Human DevelopmentWorld Bank GroupMichelle BacheletChairPartnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health1

01 IntroductionIf we change the beginning of the story,we change the whole story.1The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’sand Adolescents’ Health (2016-2030)2 is at theheart of the Sustainable Development Goals.3Its vision is a world in which every woman,child and adolescent realizes their rights tohealth and well-being – both physical andmental. That is a world in which they have socialand economic opportunities, and are able toparticipate fully in shaping prosperous andsustainable societies. And an essential part ofthis vision is that young children’s human rightsguarantee them the conditions they need tosurvive and thrive.4We know why this is important. The period frompregnancy to age 3 is when children are mostsusceptible to environmental influences.5 Thatperiod lays the foundation for health, well-being,learning and productivity throughout a person’swhole life, and has an impact on the health andwell-being of the next generation.6,7We know what threatens early childhooddevelopment. The biggest threats areextreme poverty, insecurity, gender inequities,violence, environmental toxins, and poormental health.6 All of these things affectcaregivers – by which we mean parents,families and other people who look afterchildren. The threats reduce these caregivers’capacity to protect, support and promoteyoung children’s development.We know what children need to developto their full potential. They need nurturingcare – the conditions that promote health,nutrition, security, safety, responsivecaregiving and opportunities for earlylearning. Nurturing care is about children,their families and other caregivers, and theplaces where they interact.We know what strengthens families andcaregivers’ capacity to support youngchildren’s development. An enablingenvironment is needed: policies, programmesand services that give families, parents andcaregivers the knowledge and resources toprovide nurturing care for young children.Community participation is a key part of thisenvironment, which also needs to considerthe diversity of children and families.A framework fornurturing careThe Nurturing Care Framework provides aroadmap for action. It builds on state-of-the-artevidence about how early childhood developmentunfolds and how it can be improved by policiesand interventions.8 It outlines: why efforts to improve health, well-beingand human capital must begin in the earliestyears, from pregnancy to age 3; the major threats to early childhooddevelopment;Nurturing care refers to conditions created by public policies, programmes and services. Theseconditions enable communities and caregivers to ensure children’s good health and nutrition, and protectthem from threats. Nurturing care also means giving young children opportunities for early learning,through interactions that are responsive and emotionally supportive.2REPORT 2018

how nurturing care protects youngchildren from the worst effects of adversityand promotes development – physical,emotional, social and cognitive; and what caregivers need in order to providenurturing care for young children.The Framework describes how a whole-ofgovernment and a whole-of-society approachcan promote nurturing care for young children.It outlines guiding principles, strategic actions,and ways of monitoring progress.Early experiences have a profound impacton children’s development. They affectlearning, health, behaviour and – ultimately– adult social relationships, well-being andearnings.9,10 The period from pregnancy toage 3 is when children are most susceptibleto environmental influences. Investing inthis period is one of the most efficient andeffective ways to help eliminate extremepoverty and inequality, boost sharedprosperity, and create the human capitalneeded for economies to diversify andgrow.11 The world is increasingly digital, whichmeans there is an ever-greater premiumon the abilities to reason, continually learn,effectively communicate and collaboratewith others – all of which originate in earlychildhood.12 We know that millions of youngchildren are not reaching their full potentialbecause of poor health, inadequate nutrition,exposure to stress, a lack of love and earlystimulation, and limited opportunities for earlylearning. The good news is that the situationis changing, thanks to current scientific andimplementation knowledge, and increasingglobal and country commitments.Early childhood development covers children aged 0–8 years (see Annex 1). This Frameworkfocuses on the period from pregnancy to age 3 because it is scientifically proven that this is a verysensitive period for brain development. Yet, in many settings, this period is not usually addressed inprogramming for early childhood development. In these earliest years, the health sector is uniquelypositioned to provide support for nurturing care. From age 3, children move into more formal preschoolsettings where the education sector plays a pivotal role. The Nurturing Care Framework is mindful thatoptimal development results from interventions in many stages of life. It focuses on the period frompregnancy to age 3 in order to draw attention to the health sector’s extensive reach, and to make use of it.3

Why this Framework now?The Sustainable Development Goals haveembraced young children’s development,seeing it as key to the transformation that theworld seeks to achieve by 2030.3 Embeddedin the SDGs on hunger, health, educationand justice are targets on malnutrition, childmortality, early learning and violence – targetsthat, together with others, outline an agendafor improving early childhood development.The UN Secretary-General’s Global Strategyfor Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’Health 2016–2030 synthesized the new visionunder the objectives of Survive, Thrive andTransform.2 Never before has the opportunityfor energizing investment in early childhooddevelopment been as good as it is now. Globalinstitutions – including UNICEF, the WorldBank Group, UNESCO and the World HealthOrganization – have prioritized early childhooddevelopment in their programmes of work.13 Itis more urgent than ever that we work togetherin a unified way towards common goals. ThisFramework will help to guide the actions wemust take to achieve results.What contribution canthis Framework make?This Framework provides strategic directionsfor supporting the holistic development ofchildren from pregnancy up to age 3. It aimsto inspire multiple sectors – including health,nutrition, education, labour, finance, water andsanitation, and social and child protection – towork in new ways to address the needs of theyoungest children. It articulates the importanceof responsive caregiving and early learning asintegral components of good-quality care foryoung children. And it illustrates how existingprogrammes can be enhanced to be morecomprehensive in addressing young children’sneeds. The Framework promotes the use of4REPORT 2018local assets, it presumes adaptation to thelocal context, and it promotes ownership atcommunity level. It describes the foundations,actions and government leadership that must bein place for all children to reach their potential.The audienceThe Framework addresses a broad rangeof stakeholders. First are policy-makers andprogramme managers in ministries of health,nutrition, education, child protection, socialprotection, and other sectors, at nationaland local level. It also addresses civil-societygroups, development partners, professionalassociations, academic institutions and fundinginitiatives, both global and national. In addition,it is intended as a source of inspiration –for parliamentarians, service providers,educational institutions, the private sectorand the media – for ways in which they canhelp ensure all children develop to their fullpotential. Last, but not least, the Frameworkspeaks – through these stakeholder channels– to caregivers who provide nurturing care fortheir young children every day.The Framework calls out to all levels ofgovernment and all sectors – especially thehealth sector, whose services have extensivereach among pregnant women, families andyoung children. It asks them to: address gaps in support for the youngestchildren, complementing the education sector’swork to improve pre-primary education; work together with social protection andchild protection, to ensure the material andsocial security of families and communities,and to protect young children from neglect,violence and abuse; and help to realize the rights of all children,especially the most vulnerable, and ensure thatno child, anywhere, is left behind.

02 A case fornurturing careWe know why earlychildhood development isimportantThe science of early childhooddevelopmentOver the last three decades, scientificfindings from a range of disciplines haveconverged. They prove that, duringpregnancy and the first three years afterbirth, we lay down critical elements of ourhealth, well-being and productivity, which willlast throughout childhood, adolescence andadulthood. A new-born baby’s brain containsalmost all the neurons it will ever have.By age 2, massive numbers of neuronalconnections have been made in responseto interactions with the environment, andespecially interactions with caregivers.14This rapid brain development is driven by agenetic pattern established over hundreds ofthousands of years, but it is steered by the youngchild’s experiences. The foetus first begins toexperience the world through touch.15 Then, laterin pregnancy, come taste, sound, smell and sight.After birth, it is these senses that enable thedeveloping child to learn from their surroundingsand to adapt, physiologically and psychologically.15This early adaptive learning is what makes theperiod from pregnancy to age 3 critical, and itmodifies the way genes are expressed.16 Theseepigenetic processes occur throughout life, butin this period they create blueprints for futureadaptations to the environment.5

Because of these early developmentalprocesses, experiences in pregnancy throughto age 3 significantly affect health, learningand productivity, as well as social andemotional well-being. These effects last therest of childhood, and on into adolescence andadulthood. For example, early interventionshave been shown to substantially improveThe importanceof nurturingcare fornewborn andprematurebabiesadult cardiovascular health.17 And interpersonalskills – fostered through secure affectionaterelationships with caregivers – engenderempathy and self-control that inhibit crimeand violence.18 So, abilities created in earlychildhood not only last an individual’s life, theyalso have an effect on the next generation’shuman development.Nurturing care starts before birth, when mothers and other caregivers can starttalking and singing to the foetus.19 By the end of the second trimester of pregnancy,the growing foetus can hear. And, from birth, the baby can recognize the mother’svoice.19 Early bonding is facilitated by skin-to-skin contact, breastfeeding and thepresence of a companion to support the mother. These also build the foundationsfor optimal nutrition, quality interactions and care. Soon after birth, babies respondto faces, gentle touch and holding, as well as the soothing sound of baby talk.Caregivers soon learn to appreciate how babies respond to them, which is essentialfor the optimal development of the baby’s rapidly growing brain.14,19Scientific findings from neuroscience and developmental psychology showthat these caregiver-child interactions are highly beneficial for early childhooddevelopment, and have long-lasting effects.20 Starting from the first months, qualitytime with the baby – including smiling, touching, talking, storytelling, listening tomusic, sharing and reading books, and engaging in play – builds neural connectionsthat strengthen the child’s brain.14,21Nurturing care is necessary for all babies, but premature and low-birthweightbabies (and babies with congenital conditions) need it even more. Unfortunately,they often get less of it. Caregivers need guidance in their interaction with thesevulnerable babies, because these babies’ behaviour and responses are oftenless predictable than others’. Without nurturing care, these infants are at risk ofdifficulties in their development. These difficulties can challenge caregivers who arealready stressed by the birth of a so-called small baby.22 As a result, premature andlow-birthweight babies may receive less attention and are sometimes neglected ormaltreated, which puts them at greater risk of poor development.23 Health servicesand professionals are responsible for creating a supportive environment – beforebirth, at birth, and in the first months afterwards. They need to give caregiversinformation and advice, and to support families, particularly ones with babies whoare experiencing perinatal problems.Interventions during the neonatal period – such as kangaroo care – improveneonatal outcomes in small babies and have long-term beneficial effectsthroughout life.24 However, to produce the biggest benefits, kangaroo care mustbe accompanied by specific, enhanced nurturing care at home. Similarly, mothersof premature and low-birthweight children must be given optimal support to feedtheir babies breast milk exclusively from birth – because breast milk is the best foodfor almost all new-borns.25 There would also be greater benefits for mothers andbabies if health services gave parents information about how breast milk nurturesboth the child and the parent-child relationship.6REPORT 2018

The economics of early childhooddevelopmentWe acquire basic learning and social skills at ayoung age, and our subsequent abilities build onthese foundations. Early abilities make it easier tolearn new skills, as well as build confidence andthe motivation to learn more. Early intervention iseffective and also makes later interventions morecost-effective and more likely to succeed.11,26There are many interventions – preventive andpromotive – to improve nurturing care betweenpregnancy and age 3. These achieve moreand cost less than attempts to compensate forearly deficits with remedial interventions at laterages. There have been long-term studies incountries across the socioeconomic spectrumlooking at nutritional and psychosocialprogrammes implemented from pregnancy toage 3. These studies show that the programmeshave significant long-term benefits, includingfor adult health, well-being, education, earnings,personal relationships and social life.7,8Care beforepregnancyWithout intervention, adults who experienceadversity in early childhood are estimatedto earn close to a third less than their peers’average annual income.9 This makes it harderfor them and their families to improve theirlives, which means it is less likely their childrenwill escape poverty. These individual costs addup, constraining wealth creation and nationalearnings. Estimates show that some countriesspend less on health now than they will lose infuture from the consequences of poor growthand development in early childhood.7There is now considerable evidence abouthow children benefit from home visits thatprovide nutritional counselling, any requiredsupplements, and cognitive stimulation.27,28The benefits include improved cognitivedevelopment in childhood and increasedearnings in adulthood.10 And when participantsgrew up and had children of their own, thosechildren developed better than children in thecontrol group – which demonstrates importantinter-generational benefits.10One thing is essential to protect children’s health and development, and that is thecare their parents get, to make sure they are in good health before they conceive.29,30Care before pregnancy improves men’s and women’s physical and mental health. Italso reduces the chances of their children being born prematurely, with low birthweight,birth defects or other birth-related conditions that could hinder optimal development.Studies have defined the mechanisms by which parents’ poor metabolic andmental health before pregnancy can affect their children’s development, ininfancy and beyond.31,32 Importantly, studies also show that this transgenerationaltransmission can be mitigated by interventions to improve the parents’ healthbefore conception and to support infants’ health in the post-natal period.Interventions address the behaviour – as well as the individual and environmentalrisk factors – that contribute to poor outcomes, both in the mother and the child.These risk factors include nutrition (such as micronutrient deficiencies, and beingoverweight or obese), parents’ mental health, substance use (such as alcohol andtobacco), immunization, environmental toxins, genetic conditions, infections (suchas HIV and sexually transmitted infections), infertility, child spacing, and violence(whether in the home or outside it).33Adolescence is a critical window of opportunity for promoting and supportingcare before pregnancy. The best interventions can delay pregnancy and ensurepreparedness for it. These can help mothers, by allowing them to complete school,as well as helping children, by minimizing the probability that they will have lowbirthweight or stunting.337

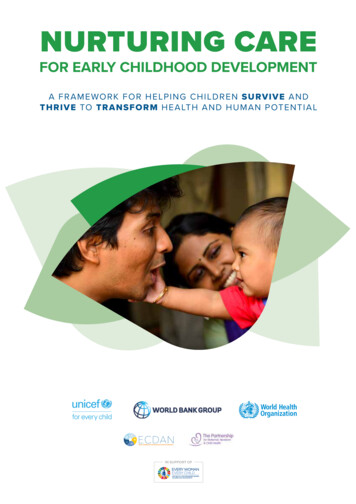

NURTURING CARE AND ITS CONTRIBUTIONS THROUGH THE LIFE COURSEInfant and toddler(up to 3 years old)Postnatal andnewbornYoung child(3-6 years old)Healthygrowth ngadolescentHealthyageingOlder child(7 to 10 yearsold)Pregnancy &childbirthPregnancy& childbirthPostnataland newbornInfant andtoddler(up to 3years old)Young child(3-6years old)Older child(7 to 10years old)Adolescence(10-19years old)Adulthood(19 10-19 years old)Adulthood(19 years)8REPORT 2018

We know what threatensearly childhood developmentHaving an optimal environment, frompregnancy to age 3, supports the baby’sphysical, emotional, social and cognitivedevelopment. And an adverse environmentharms development – both in the short termand, importantly, the longer term. Relentlessadversity – when it is severe, with no supportand no opportunity for compensation orrecovery – negatively affects young children’spsychological and neurological development.5There are threats to children’s developmentduring pregnancy and birth, as well as whenthey are new-borns, infants and toddlers.When adversity in pregnancy leads to lowbirthweight or preterm birth, this raises therisk of developmental difficulties and chronicdiseases in adulthood.6,17 Other factors thatthreaten early childhood development includeinadequate maternal nutrition, exposure toenvironmental pollutants and toxic chemicals,HIV infection, poor mental health in caregivers,sub-optimal breastfeeding, malnutrition,illnesses, injuries, limited stimulation, neglect,maltreatment, disabilities, and violence athome and in the community.6 Discriminationbetween boys and girls – and the way theyare socialized into different gender roles inchildhood – can also have negative effects onchildren’s development at this young age.34It is very difficult for families to provide carefor their young children when they are inextreme poverty or struggling for survival– amid natural disaster, displacement, waror conflict.35 This is compounded by factorsincluding young parenthood, disability,family violence, race or ethnicity-baseddiscrimination, substance abuse andmaternal depression. Threats to early childdevelopment tend to cluster together, oftenin conjunction with lack of services and socialexclusion. So being exposed to one riskusually means being exposed to many.36 Thisadversity and lack of support can underminefamilies’ capacity to provide nurturing carefor their young children. Protecting andsupporting families and caregivers – andpromoting nurturing care among them –depends on the resilience of communitiesand systems. That resilience is the result ofcoordinated action among many stakeholders– across sectors and across levels ofgovernment, both national and local.9

We know that very largenumbers of children are atrisk of poor developmentIn low- and middle-income countries,extreme poverty means an estimated 250million under-5s (43% of all under-5s inthese countries) are at risk of suboptimaldevelopment and stunted growth.6 In 7610REPORT 2018countries, an estimated 30% – or more – ofyoung children are at risk of poor learning,inadequate education and reduced adultearnings. Unprecedented numbers ofchildren live in fragile states and conditions ofviolence, war, disaster and displacement.37,38While the proportion of children at risk ishighest in countries where resources areconstrained, children all over the world areexposed to adversities that impair their optimaldevelopment. This agenda is thus truly global.

Humanitariansettings andnurturing careThe concentration of adversities amongst children living in conditions of war,disaster and displacement means they have a greater risk of impaired development,which can limit their possibilities throughout their lives. Some 250 million childrenare living in countries affected by armed conflict, while 160 million are very likely tosuffer from famine and crises of food security.39 Despite this enormous need, thereis a severe lack of early childhood development services in humanitarian settings.Approximately 2% of global humanitarian funding is spent on education, but earlychildhood development accounts for only a tiny fraction of that.39It is important to build caregivers’ capacity for nurturing care. Crisis anddisplacement threa

the right of every child to survive and thrive. We now understand that the period from pregnancy to age 3 is the most critical, when the brain grows faster than at any other time; 80% of a baby’s brain is formed by this age. For healthy brain development in these years, chil