Transcription

DConsidering palliative and end-oflife care for people with diabetesTheresa Smyth and Dion Smyth investigate the challenges of palliative and end-of-life care for people withdiabetes and observe the importance of communication between practice nurses and their patientsDuring the 20thcentury, thedemographic ofdisease and dyingfundamentally changed.Advances in modernmedicine, therapeutictechnologies and supportivecare meant that manypreviously acute causes ofdeath were successfullytransformed into chronicincurable illness so that deathoften comes only after a longperiod of progressive decline(Lynn, 2005).There are over 15 millionpeople in the UK living with along-term condition, such asdiabetes mellitus (Departmentof Health (DH), 2010).According to Diabetes UK(2011), the populationdiagnosed with diabetes is2.8 million.More than half a millionpeople die in the UK eachyear, most over the age ofT h e r e s a S m y t h is nune consultant indiabetes, Diabetes Centre, University HospitalBirmingham NHS Foundation Trust andD i o n S m y t h is senior lecturer in cancerand palliative care, Birmingham CityUniversitySubmitted IS August 2011; accepted forI publication following peer review 2S OctoberKey w o r d s : Diabetes, older people,cognitive decline, end-of-life care, palliativei careSeries Editor: A n n e Phillips is seniorlecturer in diabetes care, Alcuin C College.Department of Health Sciences, University ofYork57875 years (DH, 2008). Themajority of these deaths occurin people with a long-termcondition, and it is estimatedthat 6-9% of those dying willhave diabetes mellitus(Rowlesetal, 2011).About half of all patientsdo not die in their preferredplace of care (Gomes andHigginson, 2006). At present,the majority of deaths (58%)occur in institutional settingssuch as NHS hospitals, 18%occur at home, 17% in carehomes, 4% in hospices and3% elsewhere (DH, 2008).A report, which investigatedcomplaints to the HealthcareCommission about hospitalcare, found that over half(54%) were associated withaspects of end-of-life care(Commission for HealthcareAudit and Inspection, 2007).Similarly, wide disparities anddissatisfaction with access tospecialist palliative careservices are reported, withonly 5% of all referredpatients having a diagnosis ofnon-malignant disease (Payneet al, 2004).The provision of effective,equitable end-of-life care thatfacilitates choice and controlshould be available to all,regardless of medicaldiagnosis and place of care(DH, 2008). Some authorsargue that palliative care is aninternational human right(Brennan, 2007; Cwyther etal, 2009) including elementsof palliative care, such asadequate access toappropriate pain relief(Lohman et al, 2010).The challenge ofpalliative careThe management of diabetesat the end of life has beenreported to be a continuing'challenge' (Budge, 2010),'complex' (McCoubrie et al,2005), and 'inconsistent'(Quinn et al, 2006a; FordDunn et al, 2006). It is alsoacknowledged that palliativecare in patients with diabetesis perceptibly different fromthe treatment of patients whodo not have advanced illness(McPherson, 2008).Vandenhaute (2010)reviewed the relevance of theapplication of standardizeddiabetes care guidelines to anend-of-life populationsuggesting that caregivershave an inclination to'overmedicate', at a timewhen interventions are likelyto be invasive, irksome,inopportune, and ineffective.All the same, the prevailingphilosophy, patient opinion,political priorities andprofessional impetusemphasize that compassionateend-of-life care is the concernof all nurses, not only thespecialist practitioners(National Council for Hospiceand Specialist Palliative CareServices (NCHSPCS), 2002;DH, 2008; Royal College ofNursing (NRC), 2011). Theshifting emphasis of healthcare provision from hospitalto primary care across thehealth continuum means it isimperative that practicenurses are able to discuss,plan, and deliver high qualityend-of-life care to patients(Pellett, 2009).End-of-life care:palliative careThe World HealthOrganization (WHO) (2002)defines palliative care as anapproach that improves thequality of life of patients andtheir families facing theproblems associated with lifethreatening illness. This isacheived through theprevention and relief ofsuffering by means of earlyidentification, impeccableassessment and treatment ofpain and other problems,physical, psychosocial andspiritual. These are a few ofmany fundamental facets ofpalliative care (Table 1).Where palliative care mightonce have been seen assynonymous with, orrelegated to terminal care,Sepúlveda et al (2002) suggestthat the definition declaresnow that the principles andpractices of palliative care donot belong solely to thediscrete end-of-lifestages butshould be applied as soon asfeasible in the course of anychronic, ultimately fatalillness.Accordingly, while 'end-oflife care' may refer primarilyPractice Nursing 201 I.Vol 22. No

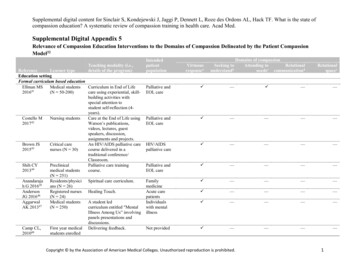

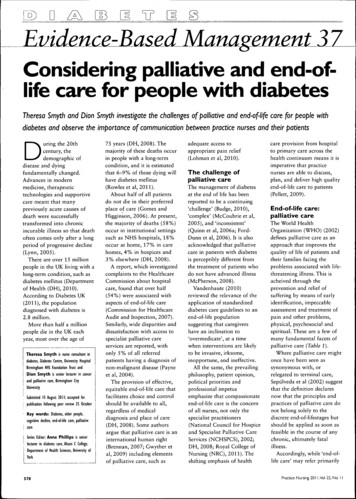

QEvidence-Based Management 3 7Table I. Principles of palliative care practiceProvides relief from pain and other distressing symptomsAffirms life and regards dying as a normal processIntends neither to hasten nor postpone deathIntegrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient careOffers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until deathOffers a support system to help family members cope during the patient'sillness and in his/her own bereavementUses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families,including bereavement counselling, if indicatedWill enhance quality of life, and may also positively influence the course ofillnessApplies to early stages of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that areintended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy andincludes those investigations needed to better understand and managedistressing clinical complicationsto the care of the dying andincorporates all elements ofthe daily life of a person inthe last part of his/her life, itis recognized that expectedlength of life is often aninexact criteria.For some conditions, suchas dementia, the use ofclinical indicator checklists,such as those within the GoldStandards Framework, wouldaid the assessment of peoplewho would profit from apalliative care approachearlier in their diseaseexperience (Alzheimer'sSociety, 2006) {Table 2).Informing people withdiabetes aboutpalliative careThe vast majority of patientswith diabetes will have longstanding type 2 diabetes andmany of these patients mayalready be known to thepractice nurse (Diabetes UK,2010). In many instances,diabetes mellitus is a commonco-morbidity of othercomplex diseases such ascancer (Smyth and Smyth,2005a; Psarakis, 2006) or canarise as a result of diabetogenic treatments, such as theuse of glucocorticosteroids580(Smyth and Smyth, 2004;Dunning et al, 2010).Whatever the aetiology, it isreasonable to expect thatmany patients with diabetesand their families have beenmanaging the diabetesindependently and well forsome time. The change inemphasis associated with endof-life care, from diseasemodification and managementto the improvement andmaintenance of quality of lifein the final months beforedeath can therefore beconfusing and distressing forpatients (Ronaldson andDevery, 2001; Randall andWearn, 2005).This is especially relevant ifpatients are not fully aware oftheir situation and involved inthe decision-making process,and lack the necessary correctinformation about whatpalliative care involves.Patients and their familiesmay perceive the cessation ofdisease-modifying treatmentand relaxation of rigorousblood glucose monitoring,control and dietary restrictionto be a lack of professionalconcern or abandonment(McCoubrie et al, 2005; Backet al, 2009).Impact of caring forpatients at end of lifeNurses should encouragepatients to shift their focus topalliative or end-of-life careduring their decline in health(Wittenberg-Lyles et al, 2011).However, it is recognized thatcare of people at the end oftheir lives, discussing aperson's impending death, andunderstanding patients'preferences for their end-oflife needs, can be a source ofsignificant stress and anxietyfor many nurses (Marks,2005; Costello, 2006;Burnard et al, 2008;Thompson-Hill et al, 2009).In one study, which exploredthe experiences of GPs andcommunity nurses discussingpatients' preferred place ofdeath, the majority of theprofessionals revealed theyfound it a difficult area ofpractice (Munday et al, 2009).The delivery of effective,high quality palliative care isdependent on confident andcompetent communicationskills (Malloy et al, 2010).Equally, being suitablyprepared may mitigate thepotentially distressing effectsof dealing with death anddying.Therefore, before anypragmatic clinicalconsiderations aboutmanaging diabetes at the endof life can be addressed,practice nurses should reflecton their communication skills,knowledge of end-of-life careand continuing professionaldevelopment needs. There areresources to assist the nurse,including a compendium oflinks to assessment tools,policy documents and clinicalguidance from organizationssuch as the Liverpool CarePathway and PreferredPriorities for Care.Clinical managementof diabetes in patientsat the end of lifeBlood glucose valuesAngelo et al (2011) haveremarked that there is adearth of evidence-basedmedical literature regardingbest practice in themanagement of patients withdiabetes who are at the end oflife, and the optimal approachremains uncertain.However, there are somegeneral observations andconsensus guidelines thatsuggest that stringentglycaemic control via regularinvasive blood glucosemonitoring might be ofdubious benefit, if notburdensome, and potentiallyTable 2 Further infbrrnationGold Standards FrameworkFor a brief discourse on the various tools on predicted prospects of patientssearch 'prognostic indicators' for some helpful linksv A/vw.goldstandardsframeworkorg.ukNational End of Life Care ProgrammePreferred Priorities for CareTo aid dialogue with patients about preferences for care at the end of lifehttD://bitlv/nRI250Royal College of NursingRoute to success: the key contribution of nursing to end of Ufe coreContains a list of useful resources from a range of organizationshttD://bitlv/o3WcGFPractice Nursing 201 I.Vol 22. No I I

uEvidence-Based Management 3 7even harmful if it causessytnptomatic hypoglycaemia(Rowles et al, 2010; Angelo etal, 2011). A target range forblood glucose of5-15mmol/litre is reasonable(Smyth and Smyth, 2005b;Rowlesetal, 2011).Type I diabetesFor patients with type 1diabetes who suffer absoluteinsulin deficiency caused bythe auto-immune destructionof the pancreas beta cells,Rowlesetal (2011)emphasized that insulinwithdrawal is 'likely to leadto death'. So insulin therapyshould be continuedpreferentially with asimplified regimen suitable tothe patient, using a oncedaily long-acting analogueinsulin, a twice-dailyisophane insulin or a twicedaily fixed mixture.Rowles also advocated theinvolvement of the specialistdiabetes team for advice andguidance with individualizedcare planning, rather thanadherence to generic treatmentprocedures in patient care; thisis especially valid for patientswith type 1 diabetes.Type' 2 diabetesFor patients with type 2diabetes, the aim ofmedication should be to avoidhypoglycaemia, whichnormally means blood glucoselevels should be less than15mtTiol/litre.Infections and treatmentwith steroids may lead tomarked hyperglycaemia whichin turn could lead todehydration and may result ina hyperosmolarhyperglycaemic state, which isassociated with unpleasantsymptoms such as polyuria,polydipsia and confusion (butS82not ketosis) and can lead todeath. As palliative care isdefined by the 'impeccableassessment and managementof symptoms' and 'intendsneither to hasten norpostpone death' (WorldHealth Organization, 2011),management to correcthyperglycaemia is appropriateand justified.Individuals suffering fromadvanced cancer or otherchronic illness commonlybecome anorexic and thereforeoral hypoglycaemic medicationis discontinued due to the riskof hypoglycaemia with insulinsecreting agents such assulphonylureas and thegastrointestinal side effects ofmetformin (Angelo et al,2011).Patients treated with insulinmay be able to discontinue thisaspect of treatment as theirendogenous insulin mayaccommodate the reduceddietary intake, weight andenergy demands. Should thepatient become symptomatic,insulin can be reinstated, e.g. aonce-daily long-acting insulinanalogue (Rowles et al, 2011).Haemoglobin A] recordingMeasuring haemoglobin A]c(HbAic), which wouldordinarily indicate whetherdiabetes was under control, islargely irrelevant in end-of-lifecare since the question orconcern of long-termcomplications is essentially ofno real therapeutic value orconsequence (Smyth andSmyth, 2005b; McPherson,2008). Even in type 1 diabetesthe frequency of blood glucosemonitoring could be reducedto daily or twice-daily.However, avoiding acutecomplications of diabetessuch as hyperglycaemia,diabetic ketoacidosis andhyperosmolar non-ketoticstates is important to theoverall goal of maintainingpatients' quality of life (Smythand Smyth, 2005b).Diabetic ketoacidosisDiabetic ketoacidosis, whichoccurs in type 1 and type 2diabetes when there is anabsolute or relatively severeinsulin insufficiency, results inbody fat being used as a fuelsource. As a result, ketones,the by-product of fatmetabolism, and acid build upin the body.Hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state, which isdistinguished by hyperglycaemia, hyperosmolarityand dehydration withoutsignificant ketoacidosis,usually presents in olderpatients with type 2 diabetesand is associated withsignificant mortality(Hemphill et al, 2011). Closecollaboration between thediabetes, palliative carespecialist practitioners andprimary care staff is vital(Quinn et al, 2006b).It is reiterated that theprofessional may be called onto communicate sensitivelythese changes to care topatients and their families in away that does not imply thesituation is hopeless or thatthere is 'nothing more that canbe done'. Instead they shouldhelp patients and their familiesto shift their focus of hope andcoping to quality of lifematters (Olsson et al, 2010).Prognostication andpalliative careEstimations of prognosis canaid self-directed decisionmaking by patients andfamilies, and afford them theopportunity to makeprovision for their future careneeds. However, a number ofresearchers have reported theintricacy and inconsistencywith end-of-lifeprognostication, includingdoctors consistentlyoverestimating the duration ofsurvival (Glare et al, 2003;Head et al, 2005).With this caveat in mind, aprognosis-based process ofprioritizing patients'treatments, grounded by theseverity of patients'circumstances and conditionhas been advocated (Angelo etal, 2011). Assorted tools to aidprognostication, such as thePalliative Performance Scale(Anderson et al, 1996) havebeen produced to provideobjective data for the predictedprospects of the patient.The 'surprise' question'would 1 be surprised if thispatient died in the next year?'is an example of astraightforward, practicable,and intuitive tool that canhelp health professionals tocontemplate the patient's careneeds and identify patientswith a poor prognosis (Mosset al, 2008; 2010; Murrayand Boyd, 2011)Angelo et al (2011) proposethree groups: Advanced disease butrelatively stable Impending death or organor system failure Actively dying.Advanced disease butrelatively stableFor patients whose conditionis stable, and they are mainlyambulant and independent,the following might beconsidered:V Continue current regimenif possible but open anhonest conversation aboutPractice Nursing 201 I,Vol 22, No I I

uEvidence-Based Management 3 7V a reduction in the intensityof glycaemic controlInstruct about preventinghypoglycaemiaCease monitoring of HbAi Reduce frequency of bloodglucose monitoringMaintain reasonableprevention ofhyperglycaemia (bloodglucose 10mmol/litre)Prescribe a relaxed'pleasure based' diet, wherethe patient eats forsatisfaction andgratification, limiting onlyhighly concentratedcarbohydrate.In addition, candidconversations with the patientshould be commenced andpeople should be offered theopportunity to discuss theirpreferred priorities of care,e.g. where they would wish todie.Impending death or organor systenn failureIn the transitional stages,when the disease advances,the patient's performancestatus is reduced, he/she isbecoming dependent and mayhave reduced intake, theimportance of glycaemiccontrol is less obvious andpreventing hypoglycaemia ismore important: Patients with type 1diabetes may need toreduce their insulin dose,especially if renal orhepatic failure is manifestsince insulin will not bemetabolized andgluconeogenesis will behindered Patients with type 2diabetes may also have todecrease their anti-diabetictreatment owing toreduced oral intake or584organ involvement thatcompromises drug activityand safety Blood glucose monitoringcan generally be stopped intype 2 diabetes and becomea decision-making toolonly, not routine practice,in type 1 diabetes.Actively dyingThe phase when a patient isactively dying it ischaracterized by the patient'sneed for total care with his/her activities of daily living,multiple organ failure and nocapacity for enterai intake,e.g. eating and drinking.Angelo et al (2011) suggestedthat consensus at this stage islacking and 'mostpractitioners' would withdrawall hypoglycaemic agentsincluding insulin in a personwith type 1 diabetes.This raises significant moral,ethical and legal considerationswhich are beyond the scope ofthis article but suggest thatopen communication betweenthe interprofessional team,with the patient where able,and his/her family and/orcarers, is vital.It also highlights one of thekey principles ofcontemporary end-of-life care,namely that realisticanticipatory planning andpreparation for the dyingprocess, including elicitingpreferred priorities for careand the patient's decision anddirection for care, can preventavoidable dilemmas ordistress.ConclusionsThe US senator, HubertHumphrey is reported to haveremarked that 'the moral testof government is how thatgovernment treats those whoare in the dawn of life, thechildren; those who are in thetwilight of life, the elderly;those who are in the shadowsof life; the sick, the needy, thehandicapped' EncyclopediaBritánica (2011).Successive governments haveraised morale and money andinvested in programmes andplans that aim to make theprovision of high quality endof-life care accessible andacceptable to all. Publicationssuch as the CommissioningDiabetes End of Life Services(NHS Diabetes, 2011) callattention to that political willand wherewithal. However, itwill be whether healthprofessionals, including nursesin general practice, are with allthe patients on their journeythat determines theprofessional success of anypolicy.Conflict of interest:-noneReferencesAnderson F, Downing GM, Hill J,Casorso L, Lerch N (1996)Palliative performance scale(PPS): a new tool./ Palliât Care12(1): 5-11Alzheimer's Society (2006) NationalEnd of Life Care Strategy forAdults: Alzheimer's Societyrecommendations to ProfessorMike Richards on a national endof life care strategy for adults.31 August, http://tiny.cc/uvkyo(accessed 24 October 2011 )Angelo M, Ruchalski C, Sproge BJ(2011 ) An approach to diabetesmellitus in hospice and palliativemedicine. / Palliât Med 4(1 ): 83-7Back AL, Young JP, McCown E et al(2009) Abandonment at the endof-lifefrom patient, caregiver,nurse, and physician perspectives:loss of continuity and lack ofclosure. Arch Intern Med 169(5):474-9Brennan, F (2007) Palliative care asan international human right.}Pain Symptom Manage 33(5):494-9Budge, P (2010) Management ofdiabetes in patients at the end oflife. Nurs Stand 25(6): 42-46Burnard P, Edwards D, Bennett K etal (2008) A comparative,longitudinal study of stress instudent nurses in five countries:Albania, Brunei, the CzechRepublic, Malta and Wales. NurseEduc Today 2S(2): 134-145Commission for Healthcare Auditand Inspection (2007) Spotlighton Complaints: A Report onSecond Stage Complaints aboutthe NHS in England. HealthcareComission, LondonCostello J (2006) Dying well:nurses' experiences o f good' and'bad' deaths in hospital. J AdvNurs 54(5): 594-601Department of Health (2008) Endof Life Care Strategy: PromotingHigh Quality Care for all Adultsat the End of Life. ExecutiveSummary. Department of Health,LondonDepartment of Health (2010)Improving the Health and WellBeing of People with Long TemíConditions. Department ofHealth, LondonDiabetes UK (2010) Diabetes in theUK 2070: Key Statistics onDiabetes. Diabetes UK, LondonDiabetes UK (2011) Reports andstatistics. Diabetes prevalence2010. http://bit.ly/lWeHeG(accessed 21 October 2011)Dunning T, Martin P, Savage S,Duggan N (2010) Guidelines forManaging Diabetes at the End ofLife. Nurses Board of Victoria,MelbourneEncyclopaedia Britannica (2011)Hubert H Humphrey. http://bit.ly/rHXqwX (accessed 21 October2011)Eord-Dunn S, Smith A, Quin J(2006) Management of diabetesduring the last days of life:attitudes of consultantdiabetologists and consultantpalliative care physicians in theUK. Palliât Med 20(3): 197-203Glare P, Virik K, Jones M et al(2003) A systematic review ofphysicians' survival predictions interminally ill cancer patients.BMJ 327(7408): 1-6Gomes B, Higginson I (2006)Factors influencing death at homein terminally ill patients withcancer: systematic review. i}MJ332(7548): 515-21Gwyther L, Brennan F, Harding R(2009) Advancing palliative careas a human right. ] PainSymptom Manage 38(5): 767-74Head B, Ritchie CR, Smoot TM(2005) Prognostication in hospicecare: can the palliativeperformance scale help? / PalliâtMed 8(3): 492-502Hemphill R, Nelson L, Sergot P(2011) Hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state. http://bit.ly/pOJxy4(accessed 12 October 2011)Practice Nursing 201 I.Vol 22. No I i

DEvidence-Based Management 3 7CASE STUDY IKEY POINTS - Compassionate end-of-lifecare is the concern of allnurses not only specialistpractitioners - Palliative care includesearly identification of lifethreatening illnesses,accurate assessment andtreatment of pain Moving focus frommodification andmanagement of diabetes tothe improvement andmaintenance of quality oflife is important for end-oflife care - Palliative care is dependenton confident and competentcommunication skillsbetv een nurse and patientLohman D, Schleifer R, Amon JJ(2010) Access to pain treatmentas a human right. BMC Med8(8): 1-9Lynn J (2005) Living long in fragilehealth: the new demographicsshape end-of-lifecare. HastingsCent Rep Spec No: S14-8National Council for Hospice andSpecialist Palliative Care Services(2002) Definitions of Supportiveand Palliative Care. Briefingpaper n. NCHSPCS, LondonNHS Diabetes (2011)Commissioning Diabetes End ofLife Care Services. NHSDiabetes, LeicesterMalloy P, Virani R, Kelly K et al(2010) Beyond bad news:communication skills of nurses inpalliative care. ] Hosp PalliâtNurs 12(3):175-6Marks JB (2005) Addressing end-oflife issues. Clinical Diabetes23(3): 98-9McCoubrie R, Jeffrey D, Paton C,Dawes L (2005) Managingdiabetes mellitus in patients withadvanced cancer: a case noteaudit and guidelines. Eur JCancer Care (EngI) 14(3): 244-8McPherson, ML (2008)Management of diabetes at endof life. Home Healthc Nurse26(5): 276-8586Tom is a 68-year-old retired mechanic, wholives with his wife, Alice. Tom has lived withtype 2 diabetes mellitus since the age of 42years. About 6 months ago he was diagnosedwith lung cancer with extensive métastases,which is associated with a poor prognosis.He is aware of his prognosis and wants to'live as much as possible' while he can.appetite, and this is a source of sometension between the couple.Tom had always striven to have goodglycaemic control, in order to preventcomplications of diabetes, but the practicenurse discusses how preventing the extremesof hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia maybe more appropriate now.Tom's weight has decreased over the pastfew months. He previously had a bodymass index of 31 kg/m' but this is now26kg/m . He complains of having 'noappetite' and when he feels like eating hewants 'just small amounts'.Tom's diabetes is treated with biphasichuman insulin twice a day, and he alsotakes metformin 1000 mg twice daily. Hehas had several hypoglycaemic episodesrecently, during which his wife had toadminister GlucoGel to help him recover.Alice is now anxious about ensuring thatTom has regular meals given his reducedHer advice to Tom is to stop taking themetformin as this can cause gastrointestinaldiscomfort and reduced appetite and shechanges the twice daily biphasic insulin to aonce-daily long-acting insulin analogue.She reassures both Tom and Alice thateating a 'pleasurable' diet when Tom feelslike it is fine. They agree that Tom shouldcontinue checking his blood glucose but onlyonce a day, to keep his blood glucosebetween 5-15mmol/litre. If it should beabove or below this range the practice nursegives him some simple dtration guidelinesfor him to adjust the insulin himself.Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Sharma S et al(2008) Utility of the 'surprise'question to identify dialysispatient with high mortality. ClinJ Am Soc Nephrol 3(5): 1379-84Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S et al(2010) Prognositic significance ofthe 'surprise' question in cancerpatients. J Palliât Med 13(7):837-40Munday D, Petrova M, Dale J(2009) Exploring preferences forpalee of death with terminally illpatients: qualitative study ofexperiences of generalpractitioners and communitynurses in England. BMJ 339:b2391Murray SA, Boyd K (2011) Using the'surprise question' can identifypeople with advanced heart failureand COPD who would benefitfrom a palliative care approach.Palliât Med 25(4): 382Olsson L, Östlund C, Strang P,Jeppsson Grassman E,Friedrichsen M (2010)Maintaining hope when close todeath: insight from cancerpatients in palliative home care.Int] Palliât Nurs 16(12): 607-12Payne S, Seymour J, Ingleton, C(2004) Overview. In: Payne S,SeymourJ, Ingleton C eds.Palliative Care Nursing:Principles and Evidence forPractice. Oxford University Press,BuckinghamPellett C (2009) Provision of end-oflifecare in the community. NursStand 24(12): 35-40Psarakis, HM (2006) Clinicalchallenges in caring for patientswith diabetes and cancer.Diabetes Spectrum 19(3): 157162Quinn K, Hudson P, Dunning T(2006a) Diabetes management inpalliative care. AustralianNursing journal 13(8): 29Quinn K, Hudson P, Dunning T(2006b) Diabetes management inpatients receiving palliative care.7 Pain Symptom Manage 32(3):275-86Ronldson S, Devery K (2001) Theexperience of transition topalliative care services:perspectives of patients andnurses. Int J Palliât Nurs 7(4):171-7Rowles S, Kilvert A, Sinclair A(2011) ABCD position statementon diabetes and end-of-lifecare.Practical Diabetes International28(1): 26-7Royal College of Nursing (2011)Route to Success: the KeyContribution of Nursing to Endof Life Care. Royal College ofNursing, LondonSepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshidn T,Ullrich A (2002) Palliative Care:the World Health Organization'sglobal perspective. ] PainSymptom Manage 24(2):91-6Smyth D, Smyth T (2004) Steroidinduced diabetes. Cancer NursingPractice i(W): 15-9Smyth D, Smyth T (2005a) Therelationship between diabetes andcancer. Journal of DiabetesNursing 9(7): 269-73Smyth T, Smyth D (2005b) How tomanage diabetes in advancedterminal illnesses. Nurs Times101(17): 30-2Thompson-Hill J, Hookey C, Salt E,O'Neill T (2009) The supportivecare plan: a tool to improvecommunication in end-of-lifecare. Int J l'alliât Nurs 15(5):250-5Vandenhaute V (2010) Palliativecare and type II diabetes: a needfor new guidelines? Am / HospPalliât Care 27(7): 444-5Wittenberg-Lyles E, Coldsmith J,Ragan S (2011) The shift to earlypalliative care: a typology ofillness journeys and the role ofnursing. Clin J Oncol Nurs 15(3):303-10World Health Organization (2011)WHO definition of palliativecare. http://bit.ly/9wlPS6Practice Nursing 201 I,Vol 22, No I I

Copyright of Practice Nursing is the property of Mark Allen Publishing Ltd and its content may not be copiedor emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission.However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

of diabetes in patients at the end of life Blood glucose values Angelo et al (2011) have remarked that there is a dearth of evidence-based medical literature regarding best practice in the management of patients with diabetes who are at the end of life, and the optimal approach remains un