Transcription

SHANE MURPHYBarn Fires:A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals

Since its founding in 1951, the Animal Welfare Institute hasbeen alleviating suffering inflicted on animals by people. AWIworks to improve conditions for the billions of animals raisedand slaughtered each year for food in the United States. Majorgoals of the organization include eliminating factory farms,supporting higher-welfare family farms, and achieving humanetransport and slaughter conditions for all farm animals.

Barn Fires:A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals1EXECUTIVE SUMMARY2INTRODUCTION TO BARN FIRES IN THEU N I T E D S TAT E S2BARN FIRES BY THE NUMBERS4T H E P R O B L E M O F B A R N F I R E S ATI N D U S T R I A L O P E R AT I O N S6S TAT E - B Y - S TAT E R E P O R T S7CAUSES OF BARN FIRES8SEASONALIT Y OF BARN FIRES8FINANCIAL COSTS OF BARN FIRES9ENTITIES RESPONSIBLE FOR MONITORINGAND REPORTING BARN FIRES11 E X I S T I N G F I R E P R O T E C T I O N F O RCONFINED ANIMALS13 R E C O M M E N DAT I O N S16 A P P E N D I X20 R E F E R E N C E SJanuary 2022 (2nd edition)About the Research This report presents an analysis of data compiledfrom barn fires that occurred over a period of fouryears, from 2018 to 2021. Information on barn fireswas obtained via media reports and public recordsprovided by the Federal Emergency ManagementAgency (FEMA) through the Freedom of InformationAct (FOIA). The term “barn” includes industrialconfinement sheds typically associated withconcentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) inaddition to the more traditional barns commonly seenon family farms. Because laws and regulations varyfrom state to state, and municipalities are not generallyrequired to report barn fires and livestock losses thatoccur within their boundaries, we acknowledge thatthere are unreported fires and animal deaths that ouranalysis does not account for.This Animal Welfare Institute (AWI) report wasprepared by Allie Granger, Farm Animal ProgramPolicy Associate, with assistance from Dena Jones,Farm Animal Program Director, and AWI policy internsMarissa Boland, Samantha Maybury, and Lucía Chambi.C U R TO I C U R TOIn This Report

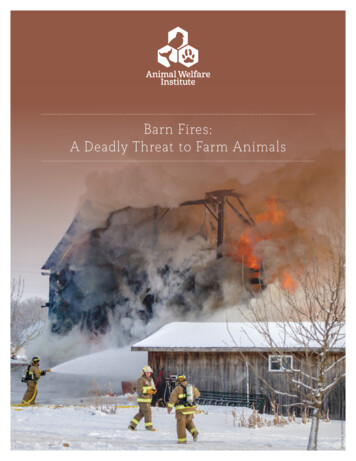

1Executive Summary This report explores the prevalence and causes offarm animal deaths due to barn fires in the UnitedStates. AWI tracked and compiled informationon barn fires over a four-year period in order todetermine why they occur, how frequently farmanimals die as a result, and how barn fires can beprevented. This is an update of a 2018 AWI report,and represents the second edition of the firstever report conducted to quantify farm animallosses from barn fires across the United States.Key findings include: From 2018 to 2021, at least 2,992,867 farmanimals died as a result of barn fires. Dueto unreported fires, it is likely that thenumber of deaths is significantly higher. Improper use of or malfunctioning heatingdevices and other electrical malfunctionswere suspected or determined to be theculprit in a large majority of barn fires. While many barn fires occurred in stateswith the most significant animal agricultureproduction, a disproportionate numberoccurred in northeastern and midwesternstates with lower levels of animal agricultureproduction. This suggests that colderweather was a greater factor in theprevalence of barn fires than the intensityof a state’s animal agriculture production. A state’s overall intensity of productionwas also not a primary factor in totalnumber of deaths, but weather was nota determining factor, either. Rather, whatdistinguished those states with the highestnumber of deaths via barn fires is that,in most, one or two catastrophic firestook the lives of hundreds of thousandsof animals at once and accounted fornearly the entire death toll in the state. The 10 largest fires that occurredbetween 2018 and 2021 (roughly 2percent of the total number of barnfires during this period) are responsiblefor the deaths of about 75 percent ofthe total number of animals killed. All10 of these fires involved chickens.M AT E U S B A N D E I R A The number of bird deaths per yearvastly outnumbered those of otherspecies. Of the nearly 3 million farmanimals killed in barn fires during thetime period studied, nearly 98 percentwere poultry, with egg-laying hensaccounting for the largest share of fatalities,followed by chickens raised for meat. There are no federal laws in the UnitedStates specifically designed to protectfarm animals from barn fires, and onlya few states have adopted NFPA 150,Fire and Life Safety in Animal HousingFacilities Code—a standard that offerssome level of protection for farm animals.Barn Fires: A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals

2Introduction to Barn Fires in theUnited States It is horrific when an animal dies in a fire.Whether it’s a calf lost in a barn fire or aracehorse who didn’t survive a stable fire, theloss of life in this manner is something no oneever wants to see. However, the sad reality isthat hundreds of thousands of animals die fromfires every year because of the lack of mandatedfire protection in barns and industrial farms.Because farm animals are raised for food, theirdeaths may not be publicized as widely as afire at a zoo or an animal shelter, but barn fireswreak havoc on animals and farm owners alike.Trapped inside burning barns and enclosures,farm animals struggle helplessly to escape asthey endure unimaginable suffering. Some diealmost immediately as the fire burns throughthe barn; others may initially survive the fire butmust be euthanized because their bodies havebeen severely burned.No farm is immune from the devastation that abarn fire can bring; these incidents range in sizefrom one animal death at small, family-ownedfarms or in backyard flocks to large-scale fireskilling hundreds of thousands of animals at anindustrial facility. While many fires could beprevented with proper inspection, maintenance,and detection systems, only a few states acrossthe country have adopted codes that specificallyrequire fire protection measures in barns.Given the limited legal protections available forfarm animals—both generally and as it relatesto fire prevention—and the lack of reportingrequirements nationwide, it is unfortunate butno surprise that farm animal fatalities have flownunder the radar and have not been prioritized.However, with comprehensive data, the politicalwill to act, and a few significant changes made byindustry groups and farm owners alike, thousandsof farm animals every year could avoid theterrible fate of perishing in barn fires.Barn Fires by the Numbers A tally of the numbers of barn fires and animaldeaths that occurred over the past five years inthe United States, based on media reports, isshown below. It is likely, however, that the actualnumber is much higher due to barn fires that gounreported in the media.The total number of animals reportedly killed peryear varied greatly; 2018 accounted for only about5 percent of the total, whereas 2020 accountedfor nearly 56 percent, despite having just over halfthe number of fires as 2018. In 2020, however,five exceptionally large fires on commercial eggoperations accounted for over 1.5 million fatalitiescombined. In 2019, one large fire killed 250,000chickens, and in 2021, the two largest firescombined to kill 366,000 chickens—substantiallyincreasing the total fatalities in those years. Incontrast, although 2018 had a significant numberof barn fires, the largest killed 50,000 animals.Between 2018 and 2021, the average numberof animals killed in barn fires a year was over748,000 animals, compared to the yearly averageof about 552,000 farm animal deaths during thelast period studied by AWI (2013–2017).D E A D LY B A R N F I R E S P E R Y E A R2018201920202021 15618288113Total: 539FA R M A N I M A L S K I L L E D P E R Y E A R2018201920202021 157,302478,5451,675,195681,825Total: 2,992,867Barn Fires: A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals

3SPECIES OF ANIMALEighteen species of animals were reported tohave died in barn fires from 2018 to 2021. Thevast majority of those animals were chickens.This is most likely because chickens raised inindustrial settings are densely packed into sheds,at much higher numbers than other farm animalspecies. Additionally, chickens account for almost96 percent of all farm animals raised for foodin the United States each year, so as tragic as itmay be, it is not surprising they are killed in theseincidents at a similar level. During the periodsurveyed, there were several instances in which100,000 to 400,000 chickens were killed in asingle fire, whereas the largest number of cowskilled in a single fire was 548 and the largestnumber of pigs was 12,000.2,758,95092%Turkeys112,9454%Other Birds(Ducks, Geese, Quail,Pheasants, GuineaHens, Peacocks)49,6842%Pigs63,2082%Cows3,912 1%Goats, Sheep2,154 1%Horses, Alpacas,Rabbits, Donkeys,Cats, Dogs786 1%Species Not Specified1,228 1%JAC K T U M M E R SAs previously mentioned, the total number offarm animals killed (shown at right) is an estimatebased on media reports that often don’t providefull data on the number or species of animalskilled. In cases where a nonspecific number ofanimals was reported (e.g., “10–20 pigs”), themost conservative number was used when tallyinganimal deaths. When the species of animals killedwere not identified, or in cases where multiplespecies were involved and an exact numericalbreakdown for the deaths was not provided (e.g.,“numerous farm animals” or “40 chickens, ducks,rabbits, and pigs”), these incidents were recordedunder the “Species Not Specified” category.ChickensBarn Fires: A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals

4The Problem of Barn Fires atIndustrial Operations The extraordinary number of animal lives lost injust a four-year period highlights the need for fireprotection at industrial animal housing facilities,particularly commercial egg and broiler operations,where one fire can—and has—killed more animalsin a day than all of the fires combined fromanother year. In order to have the biggest impacton animal welfare and reduce the number ofanimals killed in this horrific manner, this problemmust be addressed by the country’s largestpoultry and livestock farms. Until industry groupsstart taking this problem seriously by calling ontheir members to implement fire prevention andsuppression mechanisms across the sector, wewill continue to see hundreds of thousands ofanimals burned alive each year. If any one of thesesix farms highlighted at right had comprehensivefire prevention measures in place, many animalscould have been spared tremendous suffering.B A R N F I R E S AT P O U LT R Y O P E R AT I O N SConsidering how densely chickens are packedinto industrial barns, it is no surprise that thesix fires killing the most animals occurred atcommercial egg operations, with the victimsbeing egg-laying hens. During the four-yearperiod studied, we also observed what appearedto be a rise in fires at industrial-scale cage-freeegg production facilities. In fact, five of the sixlargest fires highlighted at right occurred atcage-free operations. Between 2018 and 2021,nearly 1.8 million cage-free hens were killed. Anexact cause was not determined in most of theseincidents, though it is possible that environmentalfactors associated with the nature of cage-freehousing within industrial facilities contributed tothese fires. Scientific research has documenteddust levels up to nine times higher in cage-freehousing compared to cage housing, so it seemslikely that increased dust, alone or in combinationwith litter, may give rise to the number andseverity of fires in large, crowded cage-free barns.11.February 27, 20202Michael FoodsBloomfield, Nebraska400,000 chickens2.January 3, 20203Vande Bunte EggsOstego Township, Michigan300,000 chickens3. April 23, 20204Gemperle FarmsStanislaus County, California280,000 chickens4. July 20, 20205Red Bird Egg FarmPilesgrove, New Jersey280,000 chickens5. April 30, 20196Herbruck’s Poultry RanchIonia County, Michigan250,000 chickens6. December 17, 20207Cal-Maine FoodsDade City, Florida250,000 chickensThough the number of egg-laying hens killedin fires is certainly the highest, the number ofchickens raised for meat (referred to in theindustry as “broiler chickens”), is also substantial.During the four-year period studied, morethan 326,000 broiler chickens were killed infires across the country. Fires at large broileroperations typically involved fewer animals thanthose at commercial egg farms, but the largest ofthese incidents still involved anywhere from 9,000to 64,000 animals at once.Barn Fires: A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals

JAC K T U M M E R S5The aftermath of a fire in a chicken confinement shed.B A R N F I R E S AT P I G O P E R AT I O N SSimilar to poultry, pigs raised for meat are oftenpacked into barns by the thousands, where theyspend the majority of their lives without accessto the outdoors. Such extreme confinementwithin massive buildings provides the animalsno opportunity to escape during an emergency;once a fire ignites in the barn, high mortality isinevitable. Provided below are the five worst firesthat occurred on pig confinement operationsbetween 2018 and 2021, which together resulted inthe tragic fire-related deaths of nearly 42,000 pigs.1.May 16, 20218Woodville PorkWaseca County, Minnesota12,000 pigs2.January 12, 20219Unidentified farmGila, Illinois10,000 pigs3. May 12, 202110Pillen Family FarmBoone County, Nebraska10,000 pigs4. June 19, 201811Unidentified farmFayette County, Ohio5,000 pigs5. August 7, 202012Unidentified farmPipestone County, Minnesota4,800 pigsBarn Fires: A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals

6State-By-State Reports 0–11 fires12–23 fires24–35 fires36 firesWhile weather seemed to play a primary role inthe prevalence of barn fires, this was not the casein terms of the total number of deaths reportedby state. What distinguished states with thehighest total fatalities is that, in most, one or twocatastrophic fires took the lives of hundreds ofthousands of animals at once and accounted fornearly the entire death toll. Even in Michigan—astate that ranked high in both number of barnfires and total fatalities—two of the state’s 42 firesaccounted for 96 percent of the total ead, a more prominent factor with respectto number of fires appears to be weather.Colder states experience more barn fires,regardless of whether they are top producers.As demonstrated by the graphic below, statesreporting the most barn fires were concentratedin the midwestern and northeastern areas ofthe country, while warmer southern stateswith significant animal agriculture industriesconsistently had fewer fatal barn fires.WBarn fires that killed farm animals were reportedin 46 states from 2018 to 2021. While one mightexpect that the states with the most animalagriculture would have the highest number offires, that is generally not the case. Georgia, forinstance, which has the largest broiler chickenindustry, comprising over 2,200 farms, reportedonly four barn fires during the four-year period.13Additionally, Iowa, which is both the largest eggproducing state and largest pork-producing statein the country reported fewer than 20 barn firesover the four-year span—far lower than severalother states.143942Barn Fires: A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals544762

7Causes of Barn Fires Out of 539 total barn fires that caused farmanimal fatalities, the cause or likely cause wasreported in 179 cases, or roughly 33 percent. Inmany instances, the destruction that occurredwas too severe to determine the cause. In others,the cause was still undetermined or underinvestigation at the time of press and an updatewas never provided. In cases where the causewas confirmed or suspected, nearly two-thirdsinvolved electrical heating devices and otherelectrical malfunctions.26% Electric heating device (heat lamp, space heater) suspected14% Electric heating device (heat lamp, space heater) confirmed20% Other electrical malfunction suspected5% Other electrical malfunction confirmed17% Miscellaneous machinery (skid loader, hay squeeze, tractor,compression pump, etc.)4% ArsonT W Y L A F R A N C O I S / C E T FA14% Other (weather-related/lightning, wildfire, grass fire, vehiclecrash, spilled gas, fireworks, etc.)The aftermath of amassive pig barn fire.Sows were unableto escape from theirgestation crates andperished in the fire.Barn Fires: A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals

8Seasonality of Barn Fires Given that heating devices were the mostcommon known cause of barn fires, it is notsurprising that more fires occurred during coldermonths of the year. About 59 percent of fatalbarn fires occurred from October to March, andmore than twice as many barn fires occurred inwinter (January through March) than in summer(July through September).Jan.Feb.37% · WinterMar.Apr.May26% · SpringJun.Jul.Aug.15% · SummerSep.Oct.Nov.22% · FallDec.020406080Financial Costs of Barn Fires Losing animals to barn fires can take anexcruciating financial toll on farmers. It is notonly the cost of the animals that is so staggering,but also the barn structures themselves andthe hay, machinery, and anything else that mayhave been stored in the barn. Barn fires cancause millions of dollars in damage, particularlyon industrial farms, and it can take months torebuild. Smaller farms tend to fare worse, as theydo not have the resources to rebuild as quickly,if at all. Many small farms must rely on helpfrom the community through fundraisers anddonations in the form of funds, equipment, orlabor, just to keep their farm afloat.According to the National Fire ProtectionAssociation (NFPA), between 2014 and 2018,barn fires caused an average of 48 millionin property damage annually.15 This figure issignificantly higher than an earlier estimateby the NFPA that pegged the annual cost ofdamages from barn fires at 28 million. This—inaddition to the rising death toll—demonstratesthe problem is only continuing to escalate.16Barn Fires: A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals

9Entities Responsible for Monitoringand Reporting Barn Fires Several entities are responsible for creating andenforcing fire protection laws and regulations inthe United States. While barn fires are monitoredat the local, state, and federal levels, as well as byvarious nonprofit organizations, neither farmersnor fire departments are required to report onfarm animal fatalities, so there is currently verylittle data available.fire prevention codes, which can be throughtranscription (meaning the full code is spelledout in regulation) or by reference (meaning ajurisdiction adopts a short regulation stating thata particular model code—e.g., NFPA 150, Fire andLife Safety in Animal Housing Facilities Code—islegally enforceable as the jurisdiction’s fire safetycode).17 Fire codes are also adopted at the locallevel, and local fire officials routinely conductinspections and perform fire investigations.S TAT E A N D L O C A L A U T H O R I T I E SU N I T E D S TAT E S F I R E A D M I N I S T R AT I O NThe United States Fire Administration is partof FEMA. It was created in 1974 under theFederal Fire Prevention and Control Act, andit collects data on fires nationwide throughNFIRS. Using this system, local fire departmentsreport incidents to applicable state agenciesresponsible for collecting the data, who thentransfer the reports to NFIRS. According to theUS Fire Administration, the data are used toanalyze the severity of fires across the nation,F OTO A N D R I U SFor the most part, fire protection and control isthe responsibility of state and local governments.Each state has a fire marshal or the equivalent (inColorado, the position is known as “director of theDivision of Fire Prevention and Control”; in Hawaii,it is “chair of the State Fire Council”) who isresponsible for performing investigations followinga fire, inspecting facilities for compliance withvarious regulations, and reporting to the NationalFire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS). Thestate fire marshal is also responsible for adoptingBarn Fires: A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals

10make recommendations for national codes andstandards, and support federal legislation, amongother strategic uses.Reporting barn fires to NFIRS is not mandatory.While many fire departments choose to to doso in order to receive federal grants, some ruralfire departments opt out of reporting to NFIRS,potentially due to size, lack of resources, or otherreasons. As such, barn fires still go unreported insome cases.In order to learn more about the nature ofpast barn fires, AWI submitted a public recordsrequest through FOIA for all incident reportssubmitted to NFIRS that involved barn fireson large operations—meaning those that killed1,000 or more birds, 250 or more pigs, and 100or more cows—between 2018 and 2020. AWIrequested incident reports for 48 fires; 21 wereprovided. Unfortunately, little was learned fromthese reports regarding the cause of the fires, asmuch of the information provided was extremelyvague (i.e., the cause was simply documented as“unintentional”) or, in many cases, the cause wasundetermined. Additionally, the reports failedto document any animal fatalities. This is a hugemissed opportunity for fire officials to documentand track this information to fully understand thescope of the problem, and leaves the trackingof media reports as the only option to continuegathering this information. One significantrevelation that did emerge is that a smokedetector was present in just 1 of the 21 largeoperations for which we received incident reports.N AT I O N A L F I R E P R O T E C T I O N A S S O C I AT I O NThe NFPA is a nonprofit organization thatdevelops consensus-based codes and standardsfor fire safety. Once the codes or standards areadopted by state or local governments, theybecome mandatory. As previously mentioned,the NFPA has developed NFPA 150, Fire andLife Safety in Animal Housing Facilities Code toaddress fire protection in animal housing facilities.Chapter 17 of NFPA 150 specifically coversanimals used in agriculture that are housedindoors for commercial purposes (animals livingon feedlots and pastures and those raised inresidential-type settings are excluded).NFPA 150 has evolved substantially since its initialdevelopment in 1979, which was prompted by aseries of fires in racehorse stables. It has sincebeen amended 10 times to cover a wider rangeof species housed in various settings. A specificcategorization for agricultural animals was firstadded to the 2016 edition of NFPA 150 in orderto clarify the protections required for theseanimals under certain general provisions. For the2019 edition, NFPA 150 was completely rewrittenand changed from a standard to a code; underthis version, specific provisions were added foranimal agriculture facilities that are intended toaddress the particular hazards and safety needsof such facilities. Under the newest versionof the code, the 2022 edition, two notablechanges have been made: (1) emergency forcesmust now be notified of fire alarm signals fromagricultural housing facilities, and (2) all facilitiesmust be inspected annually to identify electrical,structural, and housekeeping fire hazards.18 Bothchanges were proposed and advocated by AWIas an active member of the NFPA’s technicalcommittee that administers NFPA 150.Compliance with NFPA 150, especially amongsome of the nation’s largest producers, has thepotential to save thousands of animal lives from agruesome death. Some of the notable standardsincorporated in the code include requirements forfire alarms and detection systems in certain areasof industrial barns (something most such barnscurrently do not have), emergency managementprograms that include fire drills and extinguishertraining for employees, and a minimum distancebetween buildings to prevent the spread of a fireto multiple buildings filled with animals.Barn Fires: A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals

11Existing Fire Protection forConfined Animals Compared to other animals living in confinement,farm animals in the United States receiveconsiderably less protection (see appendix). Itis worth noting, farm animals are also excludedfrom the federal Animal Welfare Act, whichprovides minimal protections for the classes ofanimals highlighted below, including a recentlyimplemented requirement that facilities developcontingency plans to protect animals during anemergency.NFPA 150 is an encouraging start and offersreasonable fire protection standards for barns;however, the fact that it is not mandated bystatute or regulations nationwide or includedwithin industry and third-party animal welfarecertification standards weakens its potentialimpact.CAPTIVE WILD ANIMALSThe Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA),which accredits over 240 zoos and aquariumsnationwide, requires its participating facilities tohave detection systems and fire extinguishers,provide training to staff, and conduct liveaction fire and other emergency drills annually.19Participation in the AZA is not required by law,but many zoos and aquariums in the UnitedStates do participate for public relations reasonsand to receive a number of benefits.In the animal agriculture arena, this would besimilar to an industry trade association such asthe National Chicken Council or the NationalPork Producers Council including comprehensivefire protection in their guidelines. An individualfarm or facility would not be required to comply,but it would be under great pressure to do soto receive the benefits that go along with beinga member of the particular trade association.As currently written, no standards developedby any of the major animal agriculture industrygroups require fire protection measures beyonddeveloping an emergency action plan that may ormay not include planning for a fire.L A B O R AT O R Y A N I M A L SMany animals confined for use in researchare automatically protected from fire becausethey are housed in laboratories or other areaswhere humans frequently work. In addition, theAssociation for Assessment and Accreditation ofLaboratory Animal Care International (AAALACInternational) is a voluntary program that researchfacilities can participate in, similar to the AZA forcaptive wild animals. Similar to some standardsdeveloped by animal agriculture industry groups,AAALAC International’s standards don't addressfires specifically; rather, they require a disasterplan and humane euthanasia of animals whocannot recover from disaster-related injuries. Italso requires that fire officials or police officersmust be able to reach those responsible for theanimals should a disaster occur at a time whenemployees are not typically present.20C O M PA N I O N A N I M A L SAs is the case with farm animals, there are nofederal laws or regulations protecting animals inpet stores and shelters from fires. However, inthe aftermath of tragic fires, local and state lawshave sometimes been enacted to prevent suchfires from reoccurring. In 2015, in response toseveral pet store fires, the New York City Councilpassed a bill requiring pet stores to install firesprinkler systems.21 In 2016, California passed alaw requiring fire alarm systems and sprinklersin pet boarding facilities.22 And in 2019, in theaftermath of a fire at a kennel that killed 29 dogs,Illinois passed a law requiring kennels to eitherbe staffed at all times or install a sprinkler systemor fire alarm that alerts local authorities.23 Thereare key similarities between companion animalshoused in animal shelters, pet stores, and petboarding facilities and farm animals housed inBarn Fires: A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals

JAC K T U M M E R S12Cows graze in a pasturewhile a destroyed chickenbarn still smolders aftercatching on fire.cages, stalls, and crates within barns—both aretrapped in enclosures, unable to escape duringan emergency. Yet no legislation has ever beenenacted to require fire prevention or suppressionsystems in barns, even though barn fires occurmuch more frequently than those in companionanimal housing facilities, and they kill hundreds ofthousands more animals each year.I N T E R N AT I O N A L P R O T E C T I O N SWhile NFPA 150 is the only set of standardsdesigned to protect farm animals from barn firesin the United States, international standardsalso exist. Since 2004, the World Organisationfor Animal Health (abbreviated as “OIE”—itsFrench initials) has published standards foranimal welfare that it updates periodically. LikeNFPA 150, these standards are only guidelinesfor the animal agriculture industry; they are notmandatory. However, in many instances, the USanimal agriculture industry closely follows OIErecommendations. The current version of the OIETerrestrial Animal Health Code recommends thatproducers have an emergency plan in place tomitigate the impacts of disasters, including fire.24Barn Fires: A Deadly Threat to Farm Animals

13Recommendations No farm animal deserves to die in a barn fire thatcould have been prevented. Thankfully, thereare a number of steps farmers can take—fromimproving everyday operational protocols toinvesting in structural and facility renovations—to help prevent barn fires and promote firesafety. To minimize the risk of barn fires, AWIrecommends farm owners implement thefollowing fire protection methods:action plan should include a process forevacuating animals in case of a fire. It is critical for all farm employees to befamiliar with the operation’s emergencyaction plan so they can quickly respond if afire breaks out, by attempting to extinguishthe fire and/or alerting the fire departmentbefore it overwhelms the facility. Annualfire safety training, including routine firedrills and fire extinguisher training, willensure employees are best prepared torespond to a fire.O P E R AT I O NA L ANNUAL INSPECTIONSAnnual inspections performed by thefire department can help ensure that allelectrical systems on the farm are workingproperly and that the barns are free of firehazards. This is also a great opportunity forloca

farm animal deaths due to barn fires in the United States. AWI tracked and compiled information on barn fires over a four-year period in order to determine why they occur, how frequently farm animals die