Transcription

Community Engagement in Public HealthAbstractLocal public health departments are charged with promoting overall community health and well-being and addressing the causesof disease and disability.1 To achieve these goals in the 21st century, local health departments need to engage diverse communitiesin developing a broad spectrum of solutions to today’s most pressing problems, including chronic diseases (the leading causes ofdeath), health disparities, and other complex community health issues.2Drawing from a decade of experience in a relatively large local health department in California, this paper introduces a aconceptual framework for community engagement in public health. It presents the Ladder of Community Participation as a way toillustrate a range of approaches that can be used to engage communities around both traditional and emerging public health issues.This paper highlights real life examples of Contra Costa Health Services’ community engagement practices. Based on the lessonslearned, it offers suggestions to help other local health departments enhance their own activities.AUTHORS:Mary Anne Morgan,MPH,is the Director of PublicHealth Outreach,Education andCollaboration.mmorgan@hsd.cccounty.usJennifer Lifshay, MBA,MPH, is an Evaluator/Planner in the CommunityHealth Assessment,Planning, and EvaluationGroup, Contra CostaHealth Services.jlifshay@hsd.cccounty.usThis article was producedwith partial fundingfrom The CaliforniaEndowment. The authorsacknowledge the contributions of the CCHS WritersGroup and its communityand organizational partners.Public Health Division597 Center AvenueMartinez, CA 94553IntroductionThe public health issues of the 21st century include chronic diseases (such as cancer, obesity anddiabetes), gun violence, and homelessness, as well as communicable disease and maternal and childhealth. These problems affect low-income and minority populations disproportionately and areinfluenced by the physical, social and economic environments in which people live.To address these complex health issues effectively, modern local health departments (LHDs) mustbroaden their approaches and use a spectrum of strategies to build community capacity and promotecommunity health.3, 4 Respected public health organizations around the world, including the WorldHealth Organization, recognize the importance of including community engagement in this spectrumof strategies.5 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Ten Essential Services forPublic Health outlines the core public health activities including two community engagement-relatedessential public health functions: “Inform, educate and empower people about health issues” and“Mobilize community partnerships and actions to identify and solve health problems.”6 To carryout these functions and address the public health disparities of today, local health departments mustexpand their ability to engage communities.7, 8

What is Community Engagement?Community engagement involves dynamic relationshipsand dialogue between community members and local healthdepartment staff, with varying degrees of community andhealth department involvement, decision-making and control.In public health, community engagement refers to effortsthat promote a mutual exchange of information, ideas andresources between community members and the healthdepartment. While the health department shares its healthexpertise, services and other resources with the communitythrough this process, the community can share its own wisdomand experiences to help guide public health program efforts.“Community” may include individuals, groups, organizations,and associations or informal networks that share commoncharacteristics and interests based on place-, issue-, or identitybased factors. These communities often have similar concerns,which can be shared with the health department to help createmore relevant and effective health programs.A Historical PerspectiveCommunity engagement is not a new strategy in publichealth. It has played an important role in the field over thelast century, originating in traditional public health practice andevolving in response to changing population health issues andthe need to develop additional strategies to address them.In the early 20th century, public health experts took the leadin determining the priority health issues and solutions. At thattime, public health used community engagement strategiesprimarily to control communicable diseases by mobilizingpeople to participate in mass immunization, sanitation andhygiene programs.When chronic diseases emerged as the leading causes ofdeath in the 1950s, public health recognized that social andenvironmental factors strongly influenced the development ofthese conditions. Local health departments started to involvecommunity stakeholders in developing broader solutionsto address both behavioral and environmental risk factorsassociated with these diseases. The passage of California’sProposition 99 Tobacco Tax in 1988 provided funding forhealth departments to go further in their efforts, formingcoalitions and mobilizing communities to organize andadvocate for policies to prevent tobacco use. These activitiesled to environmental and public health protective policies,changed community and social norms about smoking, anddecreased smoking rates across the country.Increasingly, LHDs have engaged diverse communities inhelping to set the local public health agenda and collectivelydetermine appropriate interventions. Reducing the healthdisparities of the 21st century will require even greatercommunity participation to harness the diverse skills, resources2and perspectives needed to identify and define issues and tocraft viable solutions.9 10 11 Even when addressing newer issuessuch as bioterrorism planning, where the health department isthe lead, sharing ownership of the agenda with communitieshas been shown to be critical to developing trust and creatingplans that incorporate local concerns.12Contra Costa’s ExperienceContra Costa Health Services (CCHS) has a long history ofdeveloping strategies for engaging communities to promote thepublic’s health.13 14 15 16 More than 20 years ago, CCHS formeda coalition of heart, lung and cancer agencies and engaged thelocal medical community to enact the nation’s first uniform,countywide legislation restricting tobacco use in public areasin the work place in all 19 cities in Contra Costa County.In 1987, CCHS established a Public and EnvironmentalHealth Advisory Board, a citizen group to advise the HealthDepartment and County Board of Supervisors on communityconcerns and emerging public health issues. In the 1990s,CCHS expanded the coalition strategy to address public healthissues ranging from childhood injury and breast cancer to gunviolence and homelessness. During this time period, CCHSlaunched the Healthy Neighborhoods Project (HNP), whichuses a community leadership development strategy to stimulateinvolvement of low-income, ethnically diverse communities inidentifying and collectively addressing their own communityhealth priorities. These community partnership andengagement approaches have been institutionalized in CCHSthrough the creation of two specific public health units, theCommunity Wellness and Prevention Program (CW&PP)and Public Health Outreach, Education and Collaborations(PHOEC).This paper shares the results of our efforts to documentand understand CCHS’ efforts in community engagement.In 2004, PHOEC organized workshops on communityparticipation strategies for public health staff and conductedin-depth interviews and surveys with Advisory Boards’ leadersand program managers to identify their most promisingcommunity engagement practices. We describe some ofthese practices here. Drawing on the lessons learned, we offersuggestions to guide local health departments in their efforts todevelop their own community engagement strategies.Like most other local health departments, Contra Costahas had limited ability to document and demonstrate adirect link between community engagement practices andimprovements in population health outcomes. Healthdepartments often lack the staff resources and the necessarydata to evaluate these kinds of long-term impacts, which cantake many years to achieve. For this reason, this article focuseson more intermediate results of community engagementwork by describing changes to the climate within the healthdepartment, the service delivery system, and in organizationalor public policies that impact the community environment.

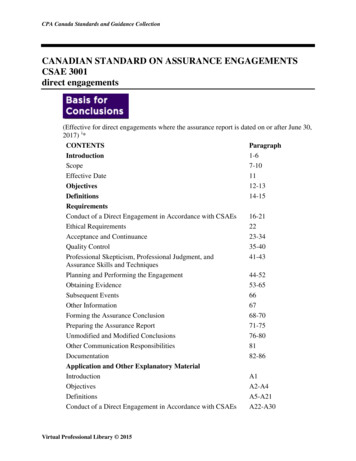

A Framework: Ladder of Community ParticipationBased on our experiences, CCHS adapted the Ladder of Community Participation17 as a tool for local health departments to use whenthinking about how to build on their existing efforts to engage communities in public health. The Ladder describes a continuumof approaches that are used even in the most traditional public health areas, such as environmental health and emergencyresponse. The strategies are arranged according to the degree of community and public health department involvement, decisionmaking and control. At the ends of the continuum, either the local health department or the community takes the lead. Betweenthese two endpoints, more balanced power-sharing can be achieved, including joint decision-making to set public health priorities,identify interventions and determine how resources will be allocated. At any level on the Ladder, ongoing communicationbetween the health department and the community is essential to foster trust and to ensure that those in the lead have thenecessary information to craft viable solutions for everyone.The Ladder of Community Participation includes seven strategies:Localhealth departmenttakes the lead and directsthe community to actHealth Department Initiatesand Directs ActionHealth Department Informs& Educates CommunityLocalhealth departmentsolicits specific, periodiccommunity inputLimited Community Input/ConsultationComprehensive CommunityConsultationCommunitymembers serve asconduits of informationand feedback to andfrom the local healthdepartmentLocalhealth departmentsolicits ongoing, in-depthcommunity inputBridgingPower-SharingCommunitymakes decisions, acts,and shares informationwith the local healthdepartmentLocalhealth departmentshares information withthe communityCommunityand local healthdepartment define andsolve problems togetherCommunity Initiates andDirects Action3

How the Ladder Can Be UsedThe Ladder of Community Participation gives public healthplanners and program managers a framework for planning,evaluating, adapting and expanding their communityengagement approaches. It can be used as a tool forinternal dialogue as programs are being planned, and may beparticularly helpful as a trigger for discussions about whichstrategies to use, and how to manage expectations, clarifyroles and delineate responsibilities. It can also be a usefulframework for discussion with community partners about howto maximize their participation and to jointly determine whichstrategies will be most suitable to achieve a particular publichealth goal.Some may see this Ladder as connotating a hierarchy, wherethe lowest rung is least desirable. However, the analogy isused here primarily to illustrate that a local health departmentcan move from one level to another in order to reach itsgoal of protecting and improving community health. Ourexperience has shown that movement among rungs occursas the health department engages communities over time andacross issues, and that there is often progression in transferof power and decision-making from the health departmentto the community. Based on the CCHS experience, the idealis to maximize community engagement and participation indecision-making whenever possible.To help bring the Ladder of Community Participation frameworkto life, the following examples highlight some promisingcommunity engagement practices drawn from our experiences.Given the dynamic nature of the model in practice, theexamples below often describe strategies that in fact havemoved between rungs as efforts have evolved and beenadapted over time.Health Department Initiatesand Directs ActionWith this option, the local health department leads decisionmaking and actions. This approach is typically employed inpublic health emergencies, such as disaster response, whenthere is a clear and immediate threat to the public’s healthand safety. In such an event, the government is obligatedto direct the community to act and to adhere to predefined,standardized safety procedures. However, experience hasshown that the community is more likely to follow publichealth directives during an emergency if it is involved in thedevelopment of these procedures and has a chance throughthat process to develop a sense of trust with the local healthdepartment.124CCHS has successfully adapted this approach in itsbioterrorism and other health emergency preparednessactivities by including a broader segment of the communityin early planning efforts. When Communicable DiseasePrograms staff developed protocols and directives to addressa possible avian flu outbreak and prepare for self-isolationand quarantine, they incorporated input gathered at a tabletopexercise. Sixty organizational and agency stakeholdersparticipated, contributing suggestions and ideas, includinginformation about how to reach monolingual Southeast Asiancommunities with appropriate instructions.Health Department Informs& EducatesThe Inform and Educate option is characterized by one-waycommunication, in which the local health department delivershealth information to the community through a variety ofmechanisms and channels. Many local health departmentscommunicate information through printed materials, such asbrochures and flyers, and electronic and other forms of media.Trained health professionals also deliver health messagesthrough one-on-one instruction or classes held in clinicalsettings.CCHS’ Community Wellness & Prevention Program (CW&PP)employs this strategy through its Asthma CommunityAdvocates (ACAs). ACAs are community residents who, unliketraditional community health workers, provide educationto community members outside of clinic sites, in day carecenters, churches and people’s homes. They not only helpcommunity members identify personal behaviors they canchange, but also conduct in-home trigger checkups to assessenvironmental risk factors. By creating a home visiting teamcomprised of the bilingual ACA and the county’s health plannurse, the health department increased its ability to respond tothe needs of monolingual families as well as expanded its focuson individual treatment to include preventive education aboutenvironmental triggers in the home.Limited Community Input/ConsultationWith the Limited Input/Consultation strategy, the local healthdepartment solicits occasional community input on predefined,discrete issues, and subsequently uses this information to makedecisions about interventions. Typically, this strategy assessescommunity needs or gathers consumer feedback related tohealth programs through surveys, interviews, focus groups, orcommunity forums.

CCHS’ Family Maternal and Child Health Programs (FMCH)took a creative approach to this strategy through their use ofPhotovoice, a process that engages community residents inrecording and reflecting upon important issues in their livesand communicating these issues to policymakers and otherswho can be mobilized to make change.18 Through theirPicture This Photovoice project, FMCH staff trained residentsto take photos reflecting their views on family, maternal andchild health assets and concerns in their community, and thenengaged them in discussions about these issues. This processhighlighted the differences between traditional FMCH issues(e.g., low birth weight, maternal mortality, and teen pregnancyprevention, etc.) and residents’ key concerns, such as the lackof afterschool resources for youth in the county. As a result ofthis input from the community, FMCH directed more of itsefforts and resources toward providing after school programsfor youth and encouraging other community agencies to do thesame.Comprehensive CommunityConsultationWith the Comprehensive Consultation strategy, local healthdepartments solicit community input on a broad rangeof issues and engage community members in helping toshape department priorities related to programs, planningand resources. This strategy requires a more substantialcommitment of resources and is characterized by ongoing andinstitutionalized mechanisms for community involvement, suchas advisory boards and coalitions.The Homeless Continuum of Care Advisory Board (COCB),appointed by the Contra Costa Board of Supervisors, hasrecently expanded its membership to include formerlyhomeless residents. COCB helps guide long-range planningand policy development and advises CCHS on creating andensuring an integrated service system for homeless people.While the effort to engage these formerly homeless residentsis just beginning, staff has already received invaluable feedbackabout program gaps and barriers to service delivery, based ontheir first hand experiences.BridgingThe Bridging strategy engages community members asconduits of information and feedback both to the local healthdepartment and from the health department to the community.Local health departments often use this strategy when theyhire and train individual residents to be health educators andWhen we gave communityresidents these cameras and theytook pictures of their lives, it gaveus a picture into their world thatwe didn’t know about.”Cheri Pies,Director, Family, Maternal & Child Health Programsother kinds of health workers. These bridging roles serve asinstitutionalized entry points through which diverse people andideas become part of and influence the county’s health caredelivery system. These bridging roles can also become formalmechanisms for creating a more diverse health departmentworkforce.CCHS has incorporated this strategy by establishing programsthat utilize trained community residents as communityhealth workers, patient navigators and community healthadvocates. The Bay Point Promotoras Program hires and trainsmonolingual, bi-cultural Hispanic/Latino community membersas lay health educators. These Promotoras provide traditionalhealth information, imbued with their cultural, linguistic andother local knowledge, to make it reflective of and relevantto the Hispanic/Latino community. Promotoras also bringinformation about community needs back to the healthdepartment, which has led to improvements in the health caredelivery system. In one community, Promotoras’ efforts ledto the establishment of a new shuttle service to a local healthcenter and cultural sensitivity training for clinic appointmentstaff to improve the quality of appointment services forHispanic/Latino clients.Power-SharingWith the Power-Sharing strategy, the community and localhealth department solve problems together. Although thisstrategy sometimes evolves naturally from other communityengagement efforts, it is less familiar to many local healthdepartments than the other community engagement strategies.Of all the strategies, it is likely to require the most significantcommitment of time and staff resources in order to besuccessful.5

CCHS’ Developmental Disabilities Council is a voluntaryadvisory group of clients, families, service providers and otheradvocates of the developmentally disabled community. Chairedby a community member and staffed by the health department,the Council advises the health department on services, andadvocates for the broader needs of the disabled community.One example of this group’s work illustrates the power ofpartnership between the community and the local healthdepartment. In 2002, the State was proposing devastatingbudget cuts for disabled services. A member agency of theCouncil led efforts to mobilize the disabled community to fightthese changes and health department staff provided relevanttechnical expertise to support these community efforts. Thiscollaboration led to restoration of program funding.“When we worktogether, there isno problem wecan’t solve.”Sary Tatpaporn,Resident Community OrganizerThrough its Healthy Neighborhoods Project (HNP), the healthdepartment’s PHOEC unit works directly with low-income,ethnically diverse communities and neighborhoods to jointlyidentify and respond to emerging health issues. HNP is anasset-based, community-building model19 that encouragesresidents to use their talents and resources to advocatecollectively for positive community health improvements.Health department staff educate residents about therelationship between community health and neighborhoodquality of life and train them in asset mapping, communityorganizing, and media and policy advocacy strategies. Healthdepartment organizers assist residents to form action teams,develop and implement action plans, and involve, educateand mobilize their neighbors to act on the community’s mostpressing health concerns. HNP teams have been successfulin advocating for passage of local environmental healthprotective policies, creation of a new community health centerin a geographically isolated neighborhood, and establishmentof neighborhood safety improvements such as street lightingand speed bumps to reduce gang and illicit drug activity.206Community Initiates andDirects ActionWith this option, the community makes decisions and actsindependently of the health department. In some cases,the health department has no or only a very limited role inthe activity. In these cases, communication with the healthdepartment may come in the form of community organizingand advocacy. This kind of community initiative can provide realopportunities for public health departments to respond to andsupport community-defined concerns and set the stage for futurecollaborations. The first example below highlights how dynamicand fluid community engagement can be in real life situations. Inthis case, there was movement from the initial Community Initiateslevel, to the level of Inform and Educate and finally to the Bridginglevel as the community leaders and health department began towork together to address the problem.After a chemical release occurred in 1999, the Laotian OrganizingProject in Richmond organized to voice residents’ concernsabout the Contra Costa County’s Community Warning Systemfor chemical releases. They felt that the system’s Englishlanguage telephone notification process was not reaching thecounty’s monolingual Laotian community. These residentstook their concerns directly to the Board of Supervisors. Thisled to collaboration between the Office of the Sheriff, theHealth Department’s Hazardous Materials Ombudsman, theLaotian Organizing Project, and other community and industrygroups. Three important outcomes resulted: 1) new culturallyappropriate health department efforts to educate Laotiancommunity members about how to “shelter in place” duringa chemical release or fire; 2) a new multi-lingual emergencynotification system that delivers warning alerts by phone in fourLaotian languages; and 3) further collaboration among the healthdepartment and Laotian residents to address community needsfor translators and additional mental health services, as a result ofthe trust built during this process.Contra Costa’s Monument Community Partnership (MCP) offersa different kind of example of how a local health departmentcan participate in a community initiated and directed effort. TheMCP and CCHS were funded by The California Endowment’s(TCE) Partnership for the Public’s Health Initiative in 2000.While TCE funding has ended, MCP continues to thrive andgrow. Health department staff offer their skills and expertiseto help MCP develop organizationally. By being present atPartnership meetings, staff is able to identify ways CCHS cancontribute to and further the community’s health agenda. CCHShas, for example, provided neighborhood-level data to illuminatecommunity demographics and trends, helped train and staff aresident-led Photovoice Project, provided outreach volunteerswith training in the county’s computerized resource network, andis currently working with MCP on neighborhood safety issues.

Preparing to Navigate the LadderAs health departments grapple with howbest to address today’s complex, interrelated health problems, many are lookingat ways to create stronger partnerships withcommunities where problem identification,decision-making and action can beshared. To be prepared to pursue suchcommunity engagement strategies, localhealth departments need to begin to get thefollowing elements in place:1.2.3.4.5.6.7.“As healthdepartmentemployees, we needto always rememberthat we are guests inthe community.”Understand the formal and informalnetworks, organizations, systems,procedures, and norms to enhancethe local health department’s abilityto approach the community in a waythat members feel is respectful andvaluable. Appreciate community assets,to maximize and strengthen communityresources.20Identify and leverage existinginstitutional relationshipsA formal vision of communityBuild on good relationshipsTiombe Mashama,engagement and why it is critical tothat have been establishedSeniorHealthEducatorthe local health department’s workby other healthMission and values statements thatdepartment programs or staffincorporate a commitment to listen to and act onmembers. Repair relationships andcommunity inputrebuild mistrust resulting from bad experiences. Be honest andopen about the problems encountered, acknowledging mistakesA strategic and articulated decision-making process toof the past. Demonstrate through action that the local healthidentify issues communities care about and for whichdepartment will deliver on its commitments.the local health department has responsibility, and todefine a course of action for tackling themDefine and communicate the parameters of jointA flexible structure that allows funding and resourceshealth department and community effortsto be allocated to respond to emerging communityEstablish roles in project oversight and decision-making earlyconcerns; this may include stipends or other creativeon. Be open about when the health department can sharemeans of compensation for community residentdecision-making power with the community. Where the localleaders who become more intensively involved inhealth department does not play the lead role, it can act as apublic health effortsconvener, facilitator, or technical assistance provider and canhelp tap into other resources, such as those in local governmentConsistent, visible and committed local healthand the faith community.department leaders at multiple levels within theorganization who will champion the communityProvide support to maximize and maintainengagement approachcommunity participationStaff with both public health expertise and the abilityAssess the community’s readiness and ability to engage, andto work effectively with communitiesprovide support to build their capacity to participate. Providetraining in health issues or specific skills, ongoing coaching andPolitical leaders who appreciate and understand publicmentoring, interpretation and translation services, childcare andhealth and the role the community plays in achievingfood and transportation to events.public health goals8. Humility and a sense of humorTips for SuccessOnce a health department commits to using or expandingits community engagement strategies and lays the internalfoundation necessary before launching such efforts, here aresome tips for making these efforts successful:Honor and build on community interests,priorities and assetsLearn as much as possible about the community beforedeveloping strategies to engage them. Communities are morelikely to want to work with the local health department iftheir own priorities are recognized and incorporated into ashared agenda. Identify community interests and concerns inorder to create links between community priorities and publichealth goals.Document and communicate the link betweencommunity engagement strategies and improvedpublic health outcomesMeasure the impact of community involvement on communityhealth. Changes in community health can take many years to berealized. Document intermediate milestones along the road toimproved health and use creative methods to measure such asimprovements to the health care system, increased utilizationof services and other factors demonstrating institutional andorganizational change. Incorporate community residents’ ideasabout how they would measure success.7

SummaryLocal health departments cannot act alone to create healthy communities. Many recognize the need to engage communitiesin public health and already do so. In Contra Costa, we have found that engaging communities in a variety of ways has hadnumerous positive results. It has increased the community’s understanding and appreciation of public health, built trust andcredibility between the health department and the residents, facilitated the genuine involvement of communities that have beentraditionally absent from the planning process, and helped create a broad constituency that can advocate on behalf of localcommunity health concerns.Local health departments must continue to test, refine and share their work and power with communities and others as we tacklethe health disparities of today. We hope that CCHS’ Ladder of Community Participation framework and the community engagementexamples presented in this paper will stimulate other local health departments to think about how to advance their own effortsand incorporate additional community engagement strategies into their work. We look forward to feedback on our work and tolearning about other local health department efforts to engage communities in promoting community health.For more information about the activities described here, or to share your examples of commu

community health.3, 4 Respected public health organizations around the world, including the World Health Organization, recognize the importance of including community engagement in this s