Transcription

PREPARINGOUR YOUTH FORAN INCLUSIVE ANDSUSTAINABLE WORLDThe OECD PISAglobal competenceframework

Foreword“Reinforcing global competence is vital forindividuals to thrive in a rapidly changingworld and for societies to progress withoutleaving anyone behind. Against a contextin which we all have much to gain fromgrowing openness and connectivity, andmuch to lose from rising inequalities andradicalism, citizens need not only the skillsto be competitive and ready for a new worldof work, but more importantly they alsoneed to develop the capacity to analyseand understand global and interculturalissues. The development of social andemotional skills, as well as values likerespect, self-confidence and a sense ofbelonging, are of the utmost importanceto create opportunities for all and advancea shared respect for human dignity. TheOECD is actively working on assessingglobal competence in PISA 2018. Together,we can foster global competence for moreinclusive societies.”Gabriela RamosOECD Chief of Staff and Sherpa to the G20“In 2015, 193 countries committedto achieving the UN’s 17 SustainableDevelopment Goals (SDGs), a shared visionof humanity that provides the missing pieceof the globalisation puzzle. The extent towhich that vision becomes a reality willdepend on today’s classrooms; and it iseducators who hold the key to ensuring thatthe SDGs become a real social contractwith citizens. Goal 4, which commits toquality education for all, is intentionallynot limited to foundation knowledge andskills such as literacy, mathematics andscience, but places strong emphasis onlearning to live together sustainably. Butsuch goals are only meaningful if theybecome visible. This has inspired theOECD Programme for International StudentAssessment (PISA), the global yardstickfor educational success, to include globalcompetence in its metrics for quality, equityand effectiveness in education. PISA willassess global competence for the first timeever in 2018. In that regard, this frameworkprovides its conceptual underpinning.”Andreas SchleicherDirector, OECD Directorate for Educationand Skills, and Special Advisor on EducationPolicy to the Secretary-GeneralThis framework is the product of a collaborative effort between the countries participating inPISA and the OECD Secretariat, under the guidance of Andreas Schleicher and Yuri Belfali.The framework was developed by Mario Piacentini with Martyn Barrett, Veronica Boix Mansilla,Darla Deardorff and Hye-Won Lee. Rose Bolognini and Natalie Foster edited the framework.Natasha Robinson provided excellent research assistance and Mattia Baiutti, helpfulcomments. This framework builds on earlier work by the experts who led the first phaseof development of the assessment: Darla Deardorff, David Kerr, Peter Franklin,Sarah Howie, Wing On Lee, Jasmine B-Y Sim and Sari Sulkinen. The OECDwould also like to thank Project Zero at Harvard University for their invaluableinput and dissemination efforts.ContentsINTRODUCTION:THE IMPORTANCE OFAN INTERNATIONALGLOBALCOMPETENCEASSESSMENTP.04THE CONCEPTOF GLOBALCOMPETENCE ANDITS IMPLICATIONSFOR EDUCATIONTHE DIMENSIONSOF GLOBALCOMPETENCEP.07THE ASSESSMENTOF GLOBALCOMPETENCEIN PISAP.21P.21P.07THE BUILDINGBLOCKS OF GLOBALCOMPETENCE– KNOWLEDGE,SKILLS, ATTITUDESAND VALUESTHE ASSESSMENTSTRATEGYSELF-REPORTEDINFORMATION INTHE STUDENTQUESTIONNAIRETHE COGNITIVETEST ON RENCESANNEXESP.39P.43ILLUSTRATIVEEXAMPLES OFSCENARIOS FORTHE COGNITIVEASSESSMENTOF GLOBALUNDERSTANDINGP.43DESCRIPTIONOF POSSIBLETOPICS FOR THESCENARIOS OF THECOGNITIVE TESTQUESTIONSRELATED TO GLOBALCOMPETENCEIN THE STUDENTQUESTIONNAIREP.46P.50

immigrants in numerous countries, communitieshave to redefine their identity and local culture.Contemporary societies call for complex formsof belonging and citizenship where individualsmust interact with distant regions, people andideas while also deepening their understandingof their local environment and the diversitywithin their own communities. By appreciatingthe differences in the communities to whichthey belong - the nation, the region, the city, theneighbourhood, the school – young people canlearn to live together as global citizens (Delorset al., 1996; UNESCO, 2014b). While educationcannot bear the sole responsibility for endingracism and discrimination, it can teach youngpeople the importance of challenging culturalbiases and stereotypes.Introduction:The importance of aninternational globalcompetence assessmentTo thrive in a changing labour marketTwenty-first century students live in aninterconnected, diverse and rapidly changingworld. Emerging economic, digital, cultural,demographic and environmental forces areshaping young people’s lives around the planet,and increasing their intercultural encounterson a daily basis. This complex environmentpresents an opportunity and a challenge. Youngpeople today must not only learn to participatein a more interconnected world but alsoappreciate and benefit from cultural differences.Developing a global and intercultural outlook isa process – a lifelong process – that educationcan shape (Barrett et al., 2014; Boix Mansillaand Jackson, 2011; Deardorff, 2009; UNESCO,2013, 2014a, 2016).What is global competence?Global competence is a multidimensionalcapacity. Globally competent individualscan examine local, global and interculturalissues, understand and appreciate differentperspectives and world views, interactsuccessfully and respectfully with others, andtake responsible action toward sustainabilityand collective well-being.Can schools promote globalcompetence?Schools play a crucial role in helping youngpeople to develop global competence. Theycan provide opportunities for young people tocritically examine global developments that are4significant to both the world at large and totheir own lives. They can teach students howto critically, effectively and responsibly usedigital information and social media platforms.Schools can encourage intercultural sensitivityand respect by allowing students to engagein experiences that foster an appreciationfor diverse peoples, languages and cultures(Bennett, 1993; Sinicrope, Norris and Watanabe,2007). Schools are also uniquely positioned toenhance young people’s ability to understandtheir place in the community and the world, andimprove their ability to make judgements andtake action (Hanvey, 1975).Educating for global competence can boostemployability. Effective communication andappropriate behaviour within diverse teams arekeys to success in many jobs, and will remainso as technology continues to make it easier forpeople to connect across the globe. Employersincreasingly seek to attract learners who easilyadapt and are able to apply and transfer theirskills and knowledge to new contexts. Workreadiness in an interconnected world requiresyoung people to understand the complexdynamics of globalisation, be open to peoplefrom different cultural backgrounds, build trustin diverse teams and demonstrate respect forothers (British Council, 2013).Why do we need globalcompetence?To use media platforms effectively andresponsiblyTo live harmoniously in multiculturalcommunitiesOver the past two decades radicaltransformations in digital technologies haveshaped young people’s outlook on theworld, their interactions with others and theirperception of themselves. Online networks,social media and interactive technologies aregiving rise to new types of learning, whereyoung people exercise greater control overwhat and how they learn. At the same time,young people’s digital lives can cause themto disconnect from themselves and the world,and ignore the impact that their actions mayhave on others. Moreover, while technologyhelps people to easily connect around theworld, online behaviour suggests that youngEducation for global competence can promotecultural awareness and respectful interactionsin increasingly diverse societies. Since theend of the Cold War, ethno-cultural conflictshave become the most common source ofpolitical violence in the world, and they showno sign of abating (Brubacker and Laitin,1998; Kymlicka, 1995; Sen, 2007). The manyepisodes of indiscriminate violence in the nameof a religious or ethnic affiliation challengethe belief that people with diverse culturesare able to live peacefully in close proximity,accept differences, find common solutions andresolve disagreements. With the high influx of OECD 2018 OECD 2018people tend to “flock together” (Zuckerman,2014) favouring interactions with a small set ofpeople with whom they have much in common.Likewise, access to an unlimited amount ofinformation is often paired with insufficientmedia literacy, meaning that young people areeasily fooled by partisan, biased or fake news.In this context, cultivating students’ globalcompetence can help them to capitalise ondigital spaces, better understand the worldthey live in and responsibly express their voiceonline.To support the Sustainable DevelopmentGoalsFinally, educating for global competencecan help form new generations who careabout global issues and engage in tacklingsocial, political, economic and environmentalchallenges. The 2030 Agenda for SustainableDevelopment recognises the critical role ofeducation in reaching sustainability goals,calling on all countries “to ensure, by 2030, thatall learners acquire the knowledge and skillsneeded to promote sustainable development,including, among others, through educationfor sustainable development and sustainablelifestyles, human rights, gender equality,promotion of a culture of peace and nonviolence, global citizenship and appreciationof cultural diversity and of culture’s contributionto sustainable development” (Target 4.7,Education 2030, Incheon Declaration andFramework for Action, page 20).Should we assess globalcompetence?Every school should encourage its studentsto try and make sense of the most pressingissues defining our times. The high demandsplaced on schools to help their students copeand succeed in an increasingly interconnectedenvironment can only be met if educationsystems define new learning objectives basedon a solid framework, and use different typesof assessment to reflect on the effectiveness oftheir initiatives and teaching practices. In thiscontext, PISA aims to provide a comprehensiveoverview of education systems’ efforts tocreate learning environments that invite youngpeople to understand the world beyond theirimmediate environment, interact with others5

with respect for their rights and dignity, and takeaction towards building sustainable and thrivingcommunities. A fundamental goal of this workis to support evidence-based decisions on howto improve curricula, teaching, assessmentsand schools’ responses to cultural diversityin order to prepare young people to becomeglobal citizens.How do we assess globalcompetence?The global competence assessment in PISA2018 is composed of two parts: a cognitiveassessment and a background questionnaire.The cognitive assessment is designed to elicitstudents’ capacities to critically examineglobal issues; recognise outside influenceson perspectives and world views; understandhow to communicate with others in interculturalcontexts; and identify and compare differentcourses of action to address global andintercultural issues.In the background questionnaire, students willbe asked to report how familiar they are withglobal issues; how developed their linguisticand communication skills are; to what extentthey hold certain attitudes, such as respect forpeople from different cultural backgrounds;and what opportunities they have at schoolto develop global competence. Answers tothe school and teacher questionnaires willprovide a comparative picture of how educationsystems are integrating global, internationaland intercultural perspectives throughout thecurriculum and in classroom activities.Taken together, the cognitive assessment andthe background questionnaire address thefollowing educational policy questions: To what degree are students able to criticallyexamine contemporary issues of local, globaland intercultural significance?The concept ofglobal competenceand its implicationsfor education To what degree are students able tounderstand and appreciate multiple culturalperspectives (including their own) andmanage differences and conflicts? To what degree are students preparedto interact respectfully across culturaldifferences? To what degree do students care about theworld and take action to make a positivedifference in other peoples’ lives and tosafeguard the environment?The dimensions of global competenceEducation for global competence buildson the ideas of different models of globaleducation, such as intercultural education,global citizenship education and educationfor democratic citizenship (UNESCO, 2014a;Council of Europe, 2016a). Despite differencesin their focus and scope (cultural differences ordemocratic culture, rather than human rightsor environmental sustainability), these modelsshare a common goal to promote students’understanding of the world and empower themto express their views and participate in society. What inequalities exist in access to educationfor global competence between and withincountries? What approaches to multicultural,intercultural and global education are mostcommonly used in school systems aroundthe world? How are teachers being prepared to developstudents’ global competence?PISA contributes to the existing models byproposing a new perspective on the definitionand assessment of global competence. Theseconceptual foundations and assessmentguidelines will help policy makers and schoolleaders create learning resources and curriculathat approach global competence as amultifaceted cognitive, socio-emotional and civiclearning goal (Boix Mansilla, 2016). They will alsofacilitate governments’ ability to monitor progressand ensure systematic and long-term support.“Competence” is not merely a specific skill butis a combination of knowledge, skills, attitudesand values successfully applied to face-to-face,virtual or mediated1 encounters with peoplewho are perceived to be from a different culturalbackground, and to individuals’ experiencesof global issues (i.e. situations that requirean individual to reflect upon and engage withglobal problems that have deep implicationsfor current and future generations). Acquiringglobal competence is a life-long process –there is no single point at which an individualbecomes completely globally competent. PISAwill assess at what stage 15-year-old studentsare situated in this process, and whether theirschools effectively address the developmentof global competence.The PISA 2018 assessment uses the followingdefinition of global competence:Global competence is the capacity toexamine local, global and interculturalissues, to understand and appreciatethe perspectives and world views ofothers, to engage in open, appropriateand effective interactions with peoplefrom different cultures, and to act forcollective well-being and sustainabledevelopment.This definition outlines four target dimensionsof global competence that people need to applysuccessfully in their everyday life:1. the capacity to examine issues and situationsof local, global and cultural significanceMediated’ here refers to encounters that occur through images in the media (for example, on television, on the Internet, ina movie or book, in a newspaper, etc.).1 ‘6 OECD 2018 OECD 20187

(e.g. poverty, economic interdependence,migration, inequality, environmentalrisks, conflicts, cultural differences andstereotypes);2. the capacity to understand and appreciatedifferent perspectives and world views;3. the ability to establish positive interactionswith people of different national, ethnic,religious, social or cultural backgrounds orgender; and4. the capacity and disposition to takeconstructive action toward sustainabledevelopment and collective well-being.Dimension 1: Examine issues of local, global and cultural significance.These four dimensions are stronglyinterdependent and overlapping, justifying theuse of the singular term “global competence”.For example, students from two differentcultural backgrounds who work together for aschool project demonstrate global competenceas they: get to know each other better (examinetheir cultural differences); try to understand howeach perceives his or her role in the projectand the other's perspective (understandperspectives); negotiate misunderstandingsand clearly communicate expectations andfeelings (interact openly, appropriately andeffectively); and take stock of what they learnfrom each other to improve social relationshipsin their classroom and school (act for collectivewell-being).This dimension refers to globally competentpeople’s practices of effectively combiningknowledge about the world and criticalreasoning whenever they form their ownopinion about a global issue. People whoacquire a mature level of development in thisdimension use higher-order thinking skills,such as selecting and weighing appropriateevidence to reason about global developments.Globally competent students can draw onand combine the disciplinary knowledge andmodes of thinking acquired in schools to askExamining issues of global significance: an exampleIn her history course, a student learns about industrialisation and economic growth indeveloping countries, and how these have been influenced by foreign investments. Shelearns that many girls of her age work in poor conditions in factories for up to ten hours a day,instead of going to school. Her teacher encourages each student to bring one item of clothingto class and look at the label to see where it was manufactured. The student is surprised tonotice that most of her clothes were made in Bangladesh. The student wonders under whatconditions her clothes were made. She looks at the websites of various high-street brandshops to see if the websites can tell her about their manufacturing standards and policies.She discovers that some clothing brands are more concerned with human rights in theirfactories than others, and she also discovers that some clothing brands have a long historyof poor conditions in their factories. She reads different journalistic articles about the issueand watches a short documentary on YouTube. Based on what she discovers, she starts tobuy fair-trade clothing and becomes an advocate for ethically responsible manufacturing.Defining culture“Culture” is difficult to define because cultural groups are always internally heterogeneousand contain individuals who adhere to a range of diverse beliefs and practices. Furthermore,the core cultural beliefs and practices that are most typically associated with any given groupare also constantly changing and evolving over time. However, distinctions may be drawnbetween the material, social and subjective aspects of culture, that is, between the materialartefacts that are commonly used by the members of a cultural group (e.g. the tools, foods,clothing, etc.), the social institutions of the group (e.g. the language, the communicativeconventions, folklore, religion, etc.), and the beliefs, values, discourses and practices thatgroup members commonly use as a frame of reference for thinking about and relating tothe world. Culture is a composite formed from all three of these aspects, consisting of anetwork of material, social and subjective resources. The full set of cultural resources isdistributed across the entire group, but each individual member of the group only uses asubset of the full set of cultural resources that is potentially available to them (Barrett et al.,2014; Council of Europe, 2016a).Dimension 2: Understand and appreciate the perspectives and world views of others.Defining culture in this way means that any kind of social group can have its own distinctiveculture: national groups, ethnic groups, faith groups, linguistic groups, occupational groups,generational groups, family groups, etc. The definition also implies that all individualsbelong to multiple groups, and therefore have multiple cultural affiliations and identities(e.g. national, religious, linguistic, generational, familial, etc.). Although all people belong tomultiple cultures, each person participates in a different constellation of cultures, and theway in which they relate to any one culture depends, at least in part, on the perspectives thatare shaped by other cultures to which they also belong. In other words, cultural affiliationsintersect, and each individual has a unique cultural positioning.This dimension highlights that globallycompetent people are willing and capable ofconsidering global problems and other people’sperspectives and behaviours from multipleviewpoints. As individuals acquire knowledgeabout other cultures’ histories, values,communication styles, beliefs and practices,they acquire the means to recognise that theirperspectives and behaviours are shaped bymultiple influences, that they are not alwaysfully aware of these influences, and that othershave views of the world that are profoundlydifferent from their own (Hanvey, 1975).People’s cultural affiliations are dynamic and fluid; what they think defines them culturallyfluctuates as an individual moves from one situation to another. These fluctuations dependon the extent to which a social context focuses on a particular identity, and on the individual’sneeds, motivations, interests and expectations within that situation (Council of Europe,2016a).8questions, analyse data and arguments, explainphenomena, and develop a position concerninga local, global or cultural issue (Boix Mansillaand Jackson, 2011). Development in thisdimension also requires media literacy, definedas the ability to access, analyse and criticallyevaluate media messages, as well as to createnew media content (Buckingham, 2007;Kellner and Share, 2005). Globally competentpeople are effective users and creators of bothtraditional and digital media.Engaging with different perspectives and worldviews requires individuals to examine theorigins and implications of others’ and their own OECD 2018 OECD 2018assumptions. This in turn implies a profoundrespect for and interest in who the other is,their concept of reality and their emotions.Individuals with this competence also accountfor and appreciate the connections (e.g. basichuman rights and needs, common experiences)that enable them to bridge differences andcreate common ground. They retain theircultural identity but are simultaneously aware ofthe cultural values and beliefs of people aroundthem. Recognising another’s position or belief isnot necessarily to accept that position or belief.However, the ability to see through ‘anothercultural filter’ provides opportunities to deepenand question one’s own perspectives, and thusmake more mature decisions when dealing withothers (Fennes and Hapgood, 1997).9

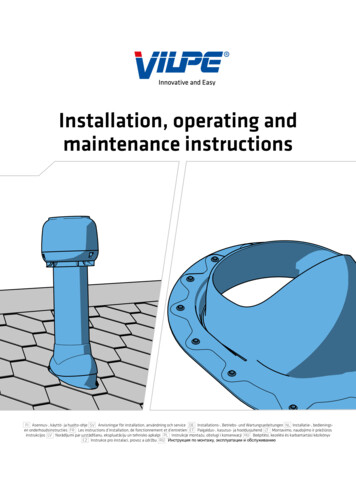

Dimension 4: Take action for collective well-being and sustainable development.Understanding perspectives and worldviews: an exampleThis dimension focuses on young people’s roleas active and responsible members of society,and refers to individuals’ readiness to respondto a given local, global or intercultural issueor situation. This dimension recognises thatyoung people have multiple realms of influenceranging from personal and local to digital andglobal. Competent people create opportunitiesto take informed, reflective action and have theirvoices heard. Taking action may imply standingup for a schoolmate whose human dignity is injeopardy, initiating a global media campaign atschool, or disseminating a personal view pointA student notices that certain members of his class have stopped eating lunch. When heenquires, they tell him that they are participating in a religious fast. The student is curiousand asks more about what that involves: for how long will they fast? When can they eat?What can they eat? What is the religious significance of the fast? The student learns thatfor his classmates fasting is something that they do every year, along with their familiesand religious community. He also learns that fasting is significant to his classmates as forthem it is a way of demonstrating control over their bodies. The student reflects on thissignificance. Although he does not fast he recognises that the themes of community,sacrifice and material transcendence are common to many different religions, including thatof his own religious heritage. He recognises that different groups can attribute the samemeaning to different practices. He furthermore asks his classmates whether he can fastwith them for a day, as a way of experiencing what fasting means for them. His classmateswarmly agree and invite him to join their families for dinner in the evening to break the fasttogether. Although the student does not attribute the same significance to fasting, throughthis experience he better understands the perspectives of his classmates and his respectfor religious diversity increases.A group of students decides to initiate an environmental awareness campaign on the ways inwhich their school contributes to local and global waste and pollution. With support from theirteachers, they arrange a series of talks on how to reduce waste and energy consumption.They also design and strategically distribute information posters that help guide studentsto make better choices when buying products and when disposing of waste. Furthermore,they collaborate with both student representatives and school administrators to introducerecycling bins and energy conservation strategies on the school premises.interact with others across differences in waysthat are open, appropriate and effective. Openinteractions mean relationships in which allparticipants demonstrate sensitivity towards,curiosity about and willingness to engage withothers and their perspectives. Appropriaterefers to interactions that respect the expectedcultural norms of both parties. In effectivecommunication, all participants are able tomake themselves understood and understandthe other (Barrett et al., 2014).Figure 1. The dimensions of global competenceleowKnInteracting openly, effectively and appropriately across cultural differences:an exampledgeUnderstandand appreciatethe perspectivesand world viewsof othersesValuExamine local,global andinterculturalissuesJo and Ai are collaborating on a school project with a student from another country, Mike. Thestudents set up a video chat on a web platform to brainstorm ideas, but at the convened timefor the meeting, they cannot find Mike online. When, a few hours later, the students manageto connect on the web platform, Jo complains that not showing up at the first meetingis not a good way to start, and gets angry when she receives no explanation at all fromMike, who remains silent at the other end of the line. At this point, Ai demonstrates globalcompetence as she successfully de-escalates the conflict. She knows that silence is usedin some cultures as a strategy to deal with perceived aggressions, and is not necessarily anadmission of guilt or indifference. She is also aware that some people refrain from speakingout directly for fear of a disagreement that may hurt the other person’s feeling and threatentheir relationship. Ai thus suspends her judgement about Mike’s behaviour and asks Mikepolitely why they could not find him online. Mike explains that this is probably due to amisunderstanding about the meeting time, as Jo and Ai’s country moved to daylight savingtime the night before while his country did not. Thanks to Ai’s intervention, the studentscould laugh about their little incident and successfully start to work on their project.SkillsGlobalcompetenceTake actionfor collectivewell-beingand sustainabledevelopmentEngage in open,appropriate andeffectiveinteractionsacross culturesdes OECD 2018 OECD 2018ituAtt10Figure 1 shows how global competenceis defined as the combination of the fourdimensions (examining issues, understandingperspectives, interacting across culturaldifferences and taking action), and how eachdimension builds on specific knowledge, skills,attitudes and values.Taking action for well-being and sustainable development: an exampleDimension 3: Engage in open, appropriate and effective interactions across cultures.This dimension describes what globallycompetent individuals are able to do whenthey interact with people from differentcultures. They understand the cultural norms,interactive styles and degrees of formality ofintercultural contexts, and they can flexiblyadapt their behaviour and communication tosuit. This dimension addresses appreciationfor respectful dialogue, desire to understandthe other and efforts to include marginalisedgroups. It emphasises individuals’ capacity toon the refugee crisis via social media. Globallycompetent people are engaged to improveliving conditions in their own communities andalso to build a more just, peaceful, inclusive andenvironmentally sustainable world.11

The building blocks of global competence – knowledge, skills, attitudesand values2The four dimensions of global competenceare supported by four inseparable factors:knowledge, skills, attitudes and values. Forexample, examining a global issue (dimension1) requires knowledge of a particular issue, theskills to transform this awareness into a deeperunderstanding, and the attitudes and valuesto reflect on the issue from multiple culturalperspectives, keeping in mind the interest ofall parties involved.Effective education for global competence givesstudents the opportunity to mobilise and usetheir knowledge, attitudes, skills and valuestogether while exchanging ideas on a globalissue in and outside of school or interactingwith people from different cultural backgrounds(for example, engaging in a debate, questioningviewpoints, asking for explanations or identifyingdirections for deeper exploration and action).A school community that wishes to nurtureglobal competence should focus on cle

Why do we need global competence? To live harmoniously in multicultural communities Education for global competence can promote cultural awareness and respectful interactions in increasingly diverse societies. Since the end of the Cold War, ethno-cultural conflicts have become the most common source of politi