Transcription

38A More Perfect Union: AmericanIndependence and the ConstitutionPart III: The Articles of ConfederationAegations that made up the Congress approveda document forming a confederation.The task of developing a political plan fellto a committee of thirteen delegates, chairedby John Dickinson of Pennsylvania. On July12, 1776, the committee submitted a draft proposal for loosely uniting the colonies. Nearlysixteen months passed before the colonial del-The legislatures of the rebellious colonies(designated as “states” by the confederation)were responsible for ratifying the plan. All except Maryland quickly approved it. (Marylandwithheld its ratification until the large statesgave up their claims to land extending to theMississippi River.) During the war years, theArticles of Confederation served as the guidingprinciples for the new nation. When Marylandfinally gave its ratification in March 1781, thefirst Constitution of what would be called the“United States of America” officially took effect.s the colonial rebellion of 1775 grew intothe War of Independence, the responsibilities of government were suddenly thruston the Continental Congress. In addition tocreating the Continental Army and issuing theDeclaration of Independence on July 4, 1776,the congressional delegates appreciated theneed to link the thirteen colonies within aformal political structure.Excerpts from the Articles of ConfederationWhereas, the delegates of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, did, on thefifteenth day of November in the year of Our Lord 1777, and in the second year of independence of America agree to certain articles of confederation and perpetual Union between thestates of [the thirteen former British colonies are listed].Article IThe stile [name] of this confederacy shall be “The United States of America.”Article IIEach state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction,and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.Article IIIThe said states hereby severally enter into a firm league of friendship with each other for theircommon defence, the security of their liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, bindingthemselves to assist each other against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them.Article IV.The free inhabitants of each of these states.shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of free citizens in the several states; and the people of each state shall have free ingressand regress [travel] to and from any other state and shall enjoy therein all the privileges oftrade and commerce, subject to the same duties [taxes], impositions and restrictions as theinhabitants thereof. Full faith and credit shall be given in each of these states to the records,acts, and judicial proceedings of the courts and magistrates of every other state.NCHOICES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY EDUCATION PROGRAMNWATSON INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, BROWN UNIVERSITYNWWW.CHOICES.EDU

A More Perfect Union: AmericanIndependence and the ConstitutionArticle VDelegates shall be annually appointed in such manner as the legislature of each state shalldirect.with a power reserved to each state, to recall its delegates, or any of them, at any timewithin the year, and to send others in their stead. No state shall be represented in Congressby less than two nor more than seven members.In determining questions in the UnitedStates in Congress assembled, each state shall have one vote.Article VI[Individual states are prohibited from making treaties with one another or foreign countrieswithout the approval of Congress. State taxes on imports in conflict with treaties made by theCongress are prohibited. Except in case of invasion, no state may engage in war without theconsent of Congress.]Article VII[When land forces are needed for common defense, the state raising the army will appoint allofficers at and under the rank of colonel.]Article VIIIAll charges of war, and all other expenses that shall be incurred for the common defence orgeneral welfare, and allowed by the United States in Congress assembled, shall be defrayedout of a common treasury which shall be supplied by the several states in proportion to thevalues of all land within each state. The taxes for paying that proportion shall be laid andlevied by the authority and direction of the legislatures of the several states within the timeagreed upon by the United States in Congress.Article IXThe United States in Congress assembled shall have the sole and exclusive right and powerof determining on peace and war,.sending and receiving ambassadors, and entering intotreaties. [The states retain the right to prohibit the importation or exportation of any goods; notreaty of commerce can restrict this.]The United States in Congress assembled shall also be the last resort on appeal in all disputesand differences now subsisting or that hereafter may arise between two or more states concerning boundary, jurisdiction, or any other cause whatever. [For each dispute, a special courtconsisting of seven to nine judges is to be created, then disbanded after the case is decided.]The court shall proceed to pronounce sentence or judgment which shall be final and decisive.[Congress is granted the authority to regulate the composition and value of coin struck by theUnited States or by individual states, to fix standard weights and measures, manage Indianaffairs, regulate post offices, appoint land and naval officers serving the United States, andmake rules regulating the land and sea forces and direct their operations.]The United States in Congress assembled shall have the authority:a) to appoint a committee to sit in the recess of Congress.and to consist of one delegate fromeach state.WWW.CHOICES.EDUNWATSON INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, BROWN UNIVERSITYNCHOICES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY EDUCATION PROGRAMN39

40A More Perfect Union: AmericanIndependence and the Constitutionb) to appoint such other committees and civil officers as may be necessary for managing the general affairs of the United States under their direction.c) to appoint one of their number to preside, provided that no person be allowed to serve in theoffice of president more than one year in any term of three years.d) to ascertain the necessary sums of money to be raised.e) to borrow money or emit bills on the credit of the United States.f) to build and equip a navy, to agree upon the number of land forces.g) [to requisition troops from the individual states proportional to their white population.].[All important issues involving war and peace and the expenditure of money will require theassent of nine state delegations, each having a single vote.]Article XThe Committee of the States, or any nine of them, shall be authorized to execute, in the recessof Congress, such of the powers of Congress as the United States in Congress assembled, bythe consent of the nine States, shall from time to time think expedient to vest them with;provided that no power be delegated to the said Committee, for the exercise of which, by theArticles of Confederation, the voice of nine States in the Congress of the United States assembled be requisite.Article XI[Canada may join on an equal footing with the original thirteen states. Any other additionsrequire the agreement of nine state delegations.]Article XII[Debts incurred by the Continental Congress before the Articles of Confederation take effectremain valid.]Article XIIIEach state shall abide by the determinations of the United States in Congress assembled on allquestions which by this confederation are submitted to them. And the articles of this confederation shall be inviolably observed by every state, and the union shall be perpetual; nor shallany alteration at any time hereafter be made in any of them unless such alteration be agreedto in a Congress of the United States and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of everystate.NCHOICES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY EDUCATION PROGRAMNWATSON INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, BROWN UNIVERSITYNWWW.CHOICES.EDU

)((1((2((3((4((5((6((7((8((9((

lain(why.((

TRB A More Perfect Union: AmericanIndependence and the ConstitutionDay Five36Name:Evaluating the Articles of ConfederationInstructions: In this exercise, your group has been called upon to analyze the pitfalls of the Articles of Confederation. You have been assigned a case study that examines a problem area typicalof the period from 1778 to 1788. After you have carefully read your case study, you and your fellowgroup members should work together to answer the questions below. Be prepared to share your conclusions with your classmates.1. Summarize the political conflict presented in your group’s case study.2. What was the main cause of the problem?3. How did the structure of the Articles of Confederation contribute to the problem?4. How did the national government address the problem?5. Who benefited from the government’s approach to the problem? Whose interests were harmed?Benefited:Harmed:6. With respect to your case study, how effectively did the confederate system function to promotethe overall good of the republic?NCHOICES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY EDUCATION PROGRAMNWATSON INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, BROWN UNIVERSITYNWWW.CHOICES.EDU

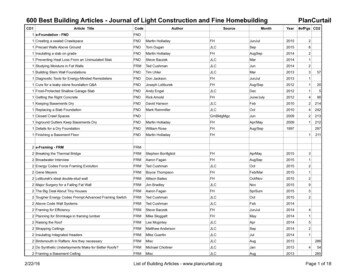

A More Perfect Union: American TRBIndependence and the ConstitutionDay Five37Name:Case Study #1—Settling the National DebtUnder the Articles of Confederation,Congress decided how much each state shouldcontribute to pay for the army and othernational expenses. Congress could borrowmoney, print paper currency, and issue loancertificates. However, the national government did not have the power to raise revenuedirectly by taxing property, individuals, orimported goods. Only the states could collect taxes. The state representatives who drewup the Articles of Confederation in 1777 hadsought to prevent the growth of a powerfulcentral government.During the War for Independence, Congress fell deep into debt. Many states failedto pay their share of the common expenses,and disputes among the states were frequent.The little gold and silver coin available wasused mostly to pay the interest on loans fromFrance and Holland. Americans who wereowed money by Congress for supplies orservices were issued loan certificates whichpromised annual interest and full payment ata future date. Congress, however, failed evento meet the annual interest payments, forcing struggling certificate holders to sell theircertificates to speculators for a fraction of theirface value. In turn, the speculators hoped thatthey would eventually be able to redeem thecertificates for close to face value.In early 1781, Congress appointed RobertMorris to serve as secretary of finance andgranted him broad powers to deal with thewartime financial crisis. Morris insisted thatthe Articles of Confederation be amended toallow Congress to impose a 5 percent tax onimports. He proposed that the revenues beearmarked for paying war debts. Twelve statelegislatures quickly agreed to the amendment.Rhode Island, however, said no. Even afterMorris hired Thomas Paine to write articlescondemning Rhode Island’s decision, thestate’s governor and legislature stood firm.They declared that the power to raise revenuewould make Congress “independent of theirconstituents [the states]; and so the proposedimpost is repugnant to the liberty of theWWW.CHOICES.EDUNUnited States.”A high-ranking Congressional delegationwas sent to Rhode Island to argue on behalfof the amendment. During their journey, thedelegates received news that the Virginia legislature had unexpectedly overturned its earlierratification of the amendment. The amendment was clearly sunk. A few months later,the American victory at Yorktown reduced thefinancial pressure on Congress.After the Treaty of Paris of 1783 wassigned, Congress owed 34 million to American creditors and 10 million to foreigncreditors. Settling the foreign debt was giventop priority, since the young nation needed tomaintain a good credit rating among foreignlenders. American creditors were forced towait.Former officers in the Continental Army,led by George Washington, demanded promptpayment for their military service. Joinedby other prominent creditors, they proddedCongress in April 1783 to propose anotherimport tax to raise revenue. Under the amendment, Congress’ power to tax imports wouldbe limited to twenty-five years and the stateswere given the authority to appoint the taxcollectors. After three years, all the statesbut New York had agreed to the compromiseplan, although some had attached conditions.Congressmen fearful of a strong national government suggested an alternative amendmentunder which the national debt would havebeen divided up and turned over to the states.They also argued that only the original holdersof the loan certificates, not speculators, shouldbe entitled to interest and full payment.In 1786, the New York legislature approved the amendment to give Congress thepower to tax imports. Congress, however,refused to accept the conditions New York imposed. Further attempts at compromise failed.Although much of the national debt was infact assumed by individual states, many creditors continued to hold seemingly worthlesscertificates.WATSON INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, BROWN UNIVERSITYNCHOICES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY EDUCATION PROGRAMN

TRB A More Perfect Union: AmericanIndependence and the ConstitutionDay Five38Name:Case Study #2—The Pirates of North AfricaDuring the second half of the eighteenthcentury, much of the North African coaststretching from the straits of Gibraltar to Egyptwas controlled by pirate chieftains. The piratessupported themselves mainly by preying onmerchant shipping in the Mediterranean Sea.Ships and cargoes that fell into their handswere sold, while the captured crew membersand passengers were either ransomed or forcedto work as slaves.Rather than going to the expense ofstationing naval forces in the region, mostEuropean countries chose to pay the piratechieftains a yearly tribute to ensure the safetyof the ships flying their national flags. Theannual cost of protection ranged from roughly 100,000 to nearly 1 million. The “Barbarypirates,” as they were called, were clever diplomats. They preyed on only a few Europeannations at a time, while temporarily maintaining peaceful relations with the others.Until 1776, Britain’s tribute to the Barbarypirates applied to colonial ships. With safeconduct passes issued by British authorities,American sea captains conducted nearly 4million worth of trade with Mediterraneanports annually. The colonial rebellion, however, ended Britain’s protection. During the war,the Americans failed to persuade the French toextend their protection to American ships.In March 1785, Congress gave John Adams,Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson theauthority to conclude treaties with the Barbarypirates and authorized 80,000 for expensesand tribute. In the meantime, American seaNCHOICES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY EDUCATION PROGRAMNcaptains used forged British and French passesto escape seizure.In July 1785, two American ships werecaptured by pirates operating from Algiers.The ruler of Algiers refused to discuss a peacetreaty with an American representative andinstead demanded 59,000 in ransom for thecrew members and passengers. The Americansremained in captivity after the negotiationsbroke down. At the same time, the ruler ofTripoli insisted that the United States providehim an annual tribute of 100,000. Again, efforts at negotiation failed.American ship owners sailing in theMediterranean were forced to pay staggeringinsurance rates. John Adams favored agreeingto the terms of the pirate chieftains, noting thatthe increased insurance rates were five timesthe cost of the tribute being demanded. In contrast, Thomas Jefferson recommended that theUnited States team up with European nationsto defeat the pirates.Jefferson’s proposal won praise in severalEuropean capitals. At home, however, Congress informed Jefferson that it would not beable to supply the funding to allow the UnitedStates to participate in the plan. Jeffersonreluctantly conceded that the United Stateshad neither the might to combat the piratesnor the finances to pay them off. Meanwhile,the Americans captured by the ruler of Algiersremained imprisoned. They were not releaseduntil 1795, after nearly 1 million in tributehad been paid.WATSON INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, BROWN UNIVERSITYNWWW.CHOICES.EDU

A More Perfect Union: American TRBIndependence and the ConstitutionDay Five39Name:Case Study #3—Soldiers in Time of PeaceOne of the key points of friction betweenthe colonists and Britain revolved around thestationing of British troops in colonial towns.Like their counterparts in Britain, colonial citizens feared that a standing army could becomea tool for imposing a tyrannical government onthe people.Suspicions toward the military did notdisappear with the outbreak of the War forIndependence. George Washington and hisgenerals regularly complained that they werenot given adequate supplies to maintain theContinental Army. Food and clothing wereoften lacking, while the enlistment bonusesand wages that had been promised to soldierswere never fully paid. The state legislaturesfrequently withheld their shares of the wareffort’s expenses. On several occasions, entireregiments threatened to mutiny over back pay.Only gifts and foreign loans enabled Washington to keep the army intact.The officers of the Continental Army wereespecially vocal in their complaints. Nearlyall of them had enlisted for the duration ofthe war. Many spent large sums of their ownmoney to equip themselves and their troops.In 1780, when colonial prospects appearedbleak, Congress promised to grant them alifelong pension equalling half their regularpay once the war was over. Within two years,however, the pledge was withdrawn.After the British surrender at Yorktownin October 1781, the officer corps grew resentful. The officers felt that they would losetheir influence over Congress once the armywas disbanded and sent home. In February1783, many of Washington’s own staff officers joined forces with prominent creditors todevise measures to pressure Congress to settleits debts. They secretly discussed a plan touse the power of the army to compel the statelegislatures to give Congress the authority toWWW.CHOICES.EDUNraise revenue. When Washington learned ofthe plot, he confronted his officers and harshlycriticized them. A military coup was averted,but the debts to the Continental Army’s soldiers remained.With Congress’s announcement on April11, 1783 that the war was officially over,Washington agreed that his troops should besent home immediately. Many of them, however, refused to put down their weapons untilthe issue of back pay was settled. After fear ofa mutiny mounted, Congress paid the troopsfor three months of service.Under the Articles of Confederation,Congress lacked the authority to maintain astanding army in peacetime. America’s entiremilitary force, stationed mostly on the frontier, consisted of fewer than seven hundredsoldiers. The officer corps, however, did notquietly disband. Many of its members believedthat they, not the politicians in Congress or thestate legislatures, were best equipped to guidethe young nation. In May 1783, they formedthe Society of Cincinnati, electing Washingtonas their president. The officers had chosen anappropriate symbol for their organization. Cincinnatus was a Roman aristocrat who agreed tolead Rome against an invading army, performed his patriotic duty, and then returned tohis farm.The formation of the Society of Cincinnatimet with opposition in the state legislaturesand in the popular newspapers. Critics saw thesociety as a powerful pressure group workingto create a military aristocracy and strengthenthe national government at the expense oflocal control. The Massachusetts legislaturedenounced the society as “dangerous to thepeace, liberty, and safety of the United States.”A journalist detected the hand of “the prime,infernal prince of hell.”WATSON INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, BROWN UNIVERSITYNCHOICES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY EDUCATION PROGRAMN

TRB A More Perfect Union: AmericanIndependence and the ConstitutionDay Five40Name:Case Study #4—The Treaty of Paris of 1783The Treaty of Paris of 1783 ended the Warof Independence and recognized American independence. It was ratified by the Congress ofthe United States, not by the individual states.In some states, opposition to provisions of thetreaty was fierce and continued to simmer overthe next five years.The treatment of the colonists who remained loyal to Britain was the thorniestissue. Perhaps 30 percent of the colonists hadsupported the mother country to some extentduring the war. Many wished to return to theirhomes after the fighting. They also hoped to becompensated for property that had been seizedor destroyed.During the conflict, every state had passed“test” laws requiring its citizens to renouncetheir allegiance to King George III. The property of loyalists had either been seized orheavily taxed. Under the Treaty of Paris, loyalists could not to be persecuted further andCongress was to recommend to the states thatreturning loyalists be allowed to seek recoveryof their property in the state courts.In defiance of the treaty, many statelegislatures and even town meetings passedresolutions opposing the return of the loyalists. The confrontation in New York, wherenearly half of the population had been loyalistat one time or another, was particular bitter.The New York legislature in 1784 passed a lawdenying the vote to anyone who had helpedthe British during the war. The law was sosweeping that two-thirds of the citizens ofNew York City and the surrounding countieswere prohibited from voting.Another controversial provision of thetreaty called on the states to permit Britishmerchants to collect the pre-war debts of theformer colonists. These debts had been payable in gold or silver coin. The planters ofMaryland and Virginia alone owed nearly 15million to British merchants. During the war,both states had passed laws enabling them topay their debts with paper currency to theirstate treasuries. In exchange, the states issuedcertificates stating that the planters were freedNCHOICES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY EDUCATION PROGRAMNfrom their debts to British creditors.While state laws in Virginia preventedBritish creditors from using state courts to suethe planters for several years, Congress openednegotiations with the British creditors. In1786, a compromise was reached in which thecreditors agreed to drop their demand for interest charges and to accept repayment in fiveannual installments. Congress insisted that thestates obey the treaty. Nonetheless, Virginiarefused to accept the agreement.At the same time, Congress lacked thepower to force Britain to withdraw its troopsfrom the Great Lakes region. Under the Treatyof Paris, Britain pledged to withdraw fromforts that fell within the new boundaries ofthe United States “with all convenient speed.”The outposts allowed Britain to control shipping in the Great Lakes and carry on the furtrade with local Indians. Despite repeatedprotests from Congress, the British held theirground.A final dispute centered around an issue not specifically covered in the Treaty ofParis—the right of Americans living west ofthe Allegheny Mountains to use the Ohio andMississippi river systems to transport theirgoods to New Orleans. The issue involved U.S.relations with Spain, since Britain had turnedover control of New Orleans and Florida toSpain after the war. The Spanish feared U.S.expansion westward and refused to permitAmericans to use the port of New Orleans.Instead, they proposed that Congress surrenderclaims to navigate the river systems for twenty-five years in exchange for Spain’s promiseto open trade between its colonies and theUnited States.Seven northern states supported theagreement, ensuring its passage in Congress.Southerners and Westerners, however, wereoutraged. James Madison labeled the agreement “treason,” while some Westernersthreatened to seize New Orleans themselvesor negotiate a separate deal with Spain. A feweven suggested rejoining Britain.WATSON INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, BROWN UNIVERSITYNWWW.CHOICES.EDU

A More Perfect Union: American TRBIndependence and the ConstitutionDay Five41Name:Case Study #5—Debtors, Creditors, and Paper MoneyIn 1783, 90 percent of America’s population lived on farms. During the war, farmproducts were in high demand by both theBritish and American armies. The Britishpaid in gold or silver, while the Americanstypically offered paper money printed by theindividual states or by Congress. Money wasplentiful.The money supply, however, quickly driedup as the war ended. The gold and silver soonflowed back to Europe to repay war debts andpurchase European imports. Moreover, Congress recommended in 1780 that the nearlyworthless paper money in circulation no longer be accepted as legal tender.The end of the war also meant that thestates had to settle the huge debts they had accumulated during the fighting. Pennsylvania,for example, owed 22 million, while Virginia’s debt was 20 million. Most of the moneywas owed to American troops or to merchantsand farmers who had supplied Americanarmies. In many states, over half of the annualbudget went toward paying interest on wardebts. During the war, the states had sold theproperty of loyalists to help offset their debts,but after 1781 they had no alternative but toraise taxes. Tax rates throughout America weremuch higher after the war than before.Many farmers found themselves in anespecially difficult situation. They weresqueezed by higher taxes, demands fromcreditors, and falling prices for their crops.Moreover, the shrinkage in the money supply meant that fewer farmers were able tofind creditors willing to lend them moneyin exchange for a mortgage on their land.Increasingly, farmers were forced to give upeverything they owned to pay their debts.Farmers banded together to fight againstforeclosure. In some areas, they reclaimedlivestock, tools, and other property that hadbeen seized by local sheriffs. Officials wereWWW.CHOICES.EDUNfrequently threatened with physical harm.Farmers also lobbied their state legislatures topass “stay laws,” which blocked the collectionof debts for six months or more.Throughout the young republic, debtorswere pitted against creditors in the politicalarena. At the center of the contest was thetopic of paper money. In seven states, debtorshad enough political clout to convince theirlegislatures to resume printing paper money.They contended that more money had to beput in circulation to enable them to take outnew loans. In the other states, creditors wonout, arguing that newly issued paper moneywould quickly lose its value. (In fact, the newpaper money proved surprisingly stable, losingless than 10 percent of its face value annually.)New York’s experience with the issuance of paper money was typical. In 1786,New York printed nearly 1 million in papermoney. The state legislature ruled that the newcurrency was to be considered legal tender forthe payment of taxes and debts. The state alsoset aside some of the money to pay its owndebts. Most important, farmers were allowedto borrow the paper money. They put up theirland as collateral to secure their loans. Whilethe expansion of the money supply did noteliminate New York’s financial crisis, pressureon the state’s debtors clearly eased.The printing of paper money sparkedthe greatest controversy in Rhode Island.Merchants there refused to accept the newcurrency and instead closed their shops. Riotsfollowed, with mobs forcing shop owners tosell their goods. Some farmers also refusedto accept paper money. As the real value ofRhode Island’s currency slipped, Congress refused to recognize it as legal tender. Congress,however, could not prevent the Rhode Islandlegislature from requiring that paper money beaccepted within the state.WATSON INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, BROWN UNIVERSITYNCHOICES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY EDUCATION PROGRAMN

TRB A More Perfect Union: AmericanIndependence and the ConstitutionDay Five42Name:Case Study #6—Western LandsDisagreements over what to do with thelands west of the Appalachian Mountainsdelayed adoption of the Articles of Confederation. In several cases, two states laid claim tothe same land based on their colonial charters.Meanwhile, states that had no claim to thewestern lands, such as Maryland and Delaware, argued that territories should be sharedamong all the states. By January 1781, thewestern lands issue had largely been resolved.States with territorial claims surrendered themto the national government, and Congresspledged that western lands would “be settledand formed into distinct republican states.”Questions surrounding settlement policyalso proved to be controversial. “Squatters”—settlers without legal title to land—demandedthat Congress recognize them as the ownersof the land they farmed. At the same time,speculators often claimed they had purchasedthousands of acres from Indian tribes. Theconflicting claims occasionally led to violence,forcing government troops to restore the peace.Most Congressmen mistrusted the settlers,who in turn had little respect for the politicalleaders of the east. Thomas Jefferson, however,championed the cause of the settlers. He sawthem as the backbone of a healthy democracybased on proud, independent small farmers.In July 1787, Congress approved a measureto settle the western lands bound by the GreatLakes, the Ohio River,

A More Perfect Union: American Independence and the Constitution Day Five 37 TRB Case Study #1—Settling the National Debt Under the Articles of Confederation, Congress decided how much each state should contribute to pay for the army and other national expenses. Congress could borrow