Transcription

IntroductoryLessonsin Aramaic:IntroductionIntroductionThe following pagesareintendedfor any individualwho is interestedin learningthebasicsof BiblicalAramaic.It is basedon lessonsI createdfor an introductoryclassin Aramaicat thelJniversityof Michigan,whereI teach.It shouldbeconsidereda work in progress.Partof the fundingfor the onlineversionof the lessonswasprovidedby a grantfrom the earemanygrammarsthatprovidean introductionto BiblicalAramaic,only oneof thesepurportsto be an introductionthatpresumesno priorknowledgeof anotherSemiticlanguage.This c,is useful,especiallyfor the oo muchon a readerbeingfamiliarwithprinciplesto serveasa tionto the studentor readerwho haslittle familiaritywith otherlanguages,(Forexample,within the first l0 pagesof areseveralreferencesto "spirantization,"thoughnogrammardoesnot includedescriptionof whatthis is.) thatdo includeexercisesfor studentsall presumethatthe studenthasa prior knowledgeof BiblicalHebrew(see,for example,AndrewE. n Introductionto Aramaic,andAlger F. Johns'sA ShortGrammorGreenspahn'sof BiblicalAramaic).I havetriedto renderthe ibleto readerswith little experiencewith grammarandlinguistics.For thisreason,the explanationsmay seemredundantfor thosewith a knowledgeoflinguisticsand/orotherlanguages.Thisis especiallytruefor the descriptionsof thepronunciationof Aramaic.It is hopedthat afterhavinggonethroughthe followinglessons,the studentwill, shouldhe or shesodesire,moveon to moresophisticatedgrammars,like Rosenthal's,or linguisticsummarieslike StuartCreason'sin TheCambridgeEncyclopediaof the World'sAncientLanguages.Oneothercaveat:the last severallessonsrely on the studentto learnvocabularyonhis or herown,by readingpassagesandlookingup wordsin the glossary.Thismimicsthe situationthatonewill be facedwith whensittinsdownwith theBibleandan Aramaicdictionarv.Introductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymond

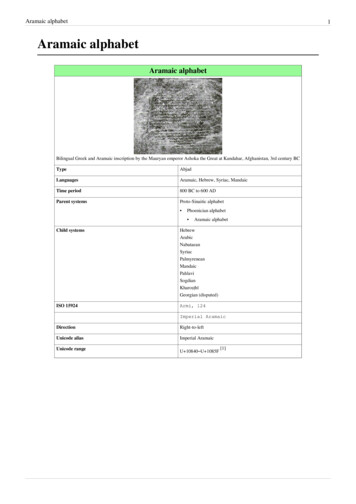

SomePreliminaries:Thealphabetthatis usedto representthe westernAramaiclanguageinpublicationsis onethatis identicalto the alphabetusedto .Theoriginsof this alphabetareinteresting,thoughto describetheseoriginswouldtaketoo muchspacehere.Sufficeit to saythatthe alphabetin its origin is Aramaic,andis oftendescribedas"AramaicBlockScript."For thisreason,I will simplyreferto the alphabetastheAramaicalphabet.Thisalphabet,like anywriting system,canbe representedwith Romanletters(thatis, thealphabetthatwe useto write English).Thisprocessof turningthe Aramaicalphabetinto Romanlettersis calledtransliteration.Thus,for example,theBiblicalAramaicword for king is representedin theAramaicalphabetas:l?F, *d in theRomanalphabetasmelek.(Aod,of course,theRomanalphabetis not specialinthis;the Aramaicalphabetcanalsorepresentanyotherwriting system.So,theEnglishword "king" canbe hansliteratedinto the Aramaicalphabet:llj?.)This actof transliterationis an advantageit allowsus to moreeasilybecauserepresentAramaicwordsin word-processingprogramsandin emailmessages.Italsohelpsto indicatewhatthe pronunciationof theword wouldbe.And, especiallyimportantfor a grammar,it forcesthe studentto sto demonstratehow muchof the grammarsheor he hasabsorbed.Transliterationdoesnot aim to representexplicitlyhow the word shouldbepronounced.It operatesby a seriesof conventionsthathaveto be learned.Sometimesthetransliterationof a word will representmarksthataregraphicallypresentin the Aramaicword,but arenot pronounced.For example,in the Aramaicwordthatcorrespondsto theEnglishphrase"he let you know,":JV-'l.l;'Th6*,{e'ek,the superscriptw in thetransliterationis not pronouncedbut indicatesthepresenceof whatcanbe describedasa "vowel-marker."Representationsof pronunciationcanbe madein severalways.I will representpronunciationswith recognizableRomanletterswithin slashmarks:/ /. This is forthe sakeof makingthe pronunciationsreadilycomprehensiblefor thebeginner.Amorescientificmethodis to usetheInternationalPhoneticAlphabet;with its manycurioussymbolsandsignsthis is sometimesconfusingfor non-specialists.Introductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymond

AbbreviationsFor PerfectandImperfectVerbalForms3ms third personmasculinesingular3fs third personfemininesingular2ms secondpersonmasculinesingular2fs secondpersonfemininesingularlcsfirst personcommonsingular3mp thirdpersonmasculineplural3fp thirdpersonfeminineplural2mp secondpersonmasculineplural2fp secondpersonfeminineplurallcpfirst personcommonpluralFor ImperativesandParticiplesm.s. masculinesingularf.s. femininesinzularpluralm.p. masculinef.p. fernininepluralForNounssing. singularpl. pluralIntroductory Lessonsin Aramqic by Eric D. Reymond

BibliographyBartelt,Andrew H. and Andrew E. Steinmann.FundamentalBiblical Hebrew/FundamentalBiblical Aramaic. St. Louis: Concordia,20A4.Bauer,Hans and lle:Max Niemeyer, 1927.Biblia Hebroica Stuttgartensia.3'oEdition. Eds. A. Alt, et al. Stuttgart:DeutscheBibelgesellschaft,1987.Brown, Francisand S.R.Driver and CharlesA. Briggs. TheBrown-Driver-BriggsHebrew and English Lexicon: With an Appendix Containing the BiblicalAramaic.Houghton,Mifflin, 1906.Creason,Stuart."Aramaic." In The CambridgeEncyclopediaof the World'sAncientLanguages.Ed. RogerD. .Greenspahn,FrederickE. An Introduction to Aramaic.2noEdition. Atlanta: Societyof Biblical Literature.2003.Johns,Alger F. A ShortGrammarof Biblical Aranaic. BerrienSprings,Mich.:Andrews University, 1972.Rosenthal,Franz.A Grammar of Biblical Aramaic. Th Edition. Wiesbaden:Harrassowitz,2006.Stevenson,William B. Gramntar of PalestinianJewishAramaic. Oxford: OxfordUniversity,1924.Waltke, Bruce and Michael O'Connor.An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Swfiax.WiononaLake.Ind.: Eisenbrauns.1990.Introductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymond

Lesson1: Consonantsform,The consonantsof Aramaicaregivenhere,togetherwith their mnunsamekh'ayin:,n)DlJpronouncedlike thepausebetweensyllablesin theof "sweater"or "better". lswe'erl,Cockneypronunciationlbe'erlby Englishspeakers.it is not pronouncedConventionallylbl (or lvl, seeLesson3)lgl (or lghl,butthetwo soundsarenotconventionallydistinguished)ld/ (or ldh/,thesoundof th in the pronunciationof theEnglishword "that")lwl or /v/ Somepeoplepronouncethis letterllke lwl,otherslike lvl. A studentshoulddecidewhichpronounciationwith andsheor he is comfortablepronounceeverywawin the sameway.lzlof "Bach"or asinlcW,asin the Germanpronunciationof the Yiddishword "Chutzpah"(or,thepronounciation"Hutzpah").no distinctionisemphatict, thoughconventionallymadein pronunciationbetweenthis t andthe tow,listedbelow.lyllW (or /ch/,seeLesson3)l\llmllnllslno approximatesoundin English,somesaylikethe soundjust beforevomiting,somesaylike thesoundof a camelgettingup, bothof which seemtoreflecta biasagainstthis phoneme.it is not pronounced.Conventionally,Introductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymond

I?-ltDUnsqr33tsadehqophresltsinshintuwemphatics: pronouncedconventionallyllke ltzllike kaphconventionallyemphatick: pronouncedlrl/s/, pronouncedconventionallylike samekh/sU asin theEnglishword shineltl (or lthl, thesoundof th in "these"[comparetothepronunciationof dqlethasidhl listedabovel;seeLesson3)Someof theseletters,like beth,havetwo differentpronunciations,aswill bewith the sameexplainedin Lesson3. .Thus,evenin caseswhere! is pronouncedlike lvl,I is stillwith theRomanletterb.transliteratedIn additionto theseletterforms,five lettershaveformsthatoccuronly at the endof a word::Tkkaph(Notethe two dotsthat arealwayswritten with the finalkaph.)Emmem'Jnnun.'lppehsadehsYNotethe similaritiesbetweencertainforms.Thebeth(3) andkoph(!) letterslooksimilar.Thesin (tlJ)andshin(W)lettersaredistinguishedby a singledot abovethem.And, the final mem(D) looksllke samekh(O).Exercise:la.-lPracticetransliteratingthe followingwords.For example, Jn -- mlk. (Notethatthetransliteratedword in theRomanalphabetis writtenandreadfrom left to right[m l k], althoughthe Aramaicscriptis written andreadfrom right to leftt-l-, -nl.)IntroductoryLessonsin Aramaicby Eric D. Reymond

N: tb("theking")I'Pnj'!'Pn("strong"in the singularandin theplural)F.trltt.jNn'lrrtFtlirJN'nl("house,""the house,""houses,"and "the houses")JIi-J) t-jliJ("he wrote"and"shewtote")-INN'l-lnN("he said"and"they said")-\ F\rtrirtqF-trtI lJllJI("he writes" and "they write")Exercise:1b.Now try puttingthesetransliteratedwordsinto Aramaicscript.Rememberthat youmustreversetheorderof the letters.Thus,rb' is renderedin AramaicscriptN:-.l.ktbkrbt("he wrote" tory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymond

ce,""well-being"),r,tr''("land" and "the land")Exercise:lc.Try transliteratingthis full Aramaicsentencefiom thebookof Ezra(4:20):E)ut-r')u ttn l'!'pn l':)nN-ln: -tlIJ )::j'b')tDllrn)rn'nnlbnrr): rityin all Abar-Nahara'andtribute,tax,andtoll wasgivento them."Exercise:I d.Now try transliteratingthis sentencefrom Ena 5:4 (slightlyalteredfor the sakeofconsistencyandcoherency):j'rn) 'l-lnNNn:: j"] 'i':l N:':: n:"1'J N"ll: nilnu'i'r:N]bIntroductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymond8

"Then,accordingly,theysaidto them,'Whatarethenamesof the menwho arebuildingthis ?"'Exercise:Le.passageNow, write in Aramaicscriptthe followingtransliteratedfrom Ezra5:5(againslightlyalteredfor consistency):w'yn 'lhhn hwt 'l Sbyyhwdy'wl' btlw hmw"The eyeof theirGodwasoverthe eldersof theJudaeansandthey(i.e.,theelders)did not lJene:Notewell):Thedoublingof a consonantis indicatedthrougha dot placedin the centerof the:letter.Thus,I b, but I : bb; ln: : ktb, but lFll : kttb.TransliteratebelowthefollowingpassagefromEna 5.6 and5:17,notingwherethedoubledconsonantsare:Nf )n lD''ln"'t'T)ls .':Fln n)u n-lNn-lr JltD-l!"A copy of the letterthat Tattenaisent . . . to Dariusthe king."):::'-Ti'TnnN:)n 'J N:T:ln'll-tr)fn'"Let a searchbe madein the houseof recordsof theking therein Babylon."IntroductoryLessonsin Aramaicby Eric D. Reymond

Lesson2: Vowelsaswell as signsthat ntsmay serveeitherasa trueandbelowthe letters.Therefore,someconsonantsareusedto markor asthe markerof a elstheyaremarkingare"long vowels."But, not every"longthat markvowelshelpConsonantswith sucha consonant.vowel" is representedmakethe pronunciationof a word moreobviousto a lectionis,Latin for "mothersof reading."it is helpfultofrom motres-consonants,In orderto distinguishtrueconsonantsrepresentthe matres-consonantsassuperscriptlettersin transcription.Althoughthe vowelsarelabeledeither"long" or "short,"this nomenclaturedoesThevowelsin BiblicalAramaicarenot describethelengthof theirpronunciation.not distinguishedthem,but ratherbyby the lengthof time it takesto pronouncetheirdistinctsounds.Thus,we will speakof a "shortla/" andthis describesa sounddistinctfrom "long la/",but bothwouldhavehadthe samequantity,i.e.,lengthofpronunciation.into theRomanLike the Aramaicconsonants,thevowelsmaybe transliteratedLong vowelsaredistinguishedfrom shortvowelsby a macron,i.e.,a linealphabet.::overthem(shortlal a;longlal a).Partl:Belowarethe vowelsignsandthe consonalltsthatsometimesaccompanythem.Inthis list, thevowel signsa"rerepresentedbeneathor abovethe letterbeth;theirpronunciationfollow.forms,andtheir like thea in themarksshortlal, conventionallyEnglishword "mat."IAmarkslong lal, conventionallypronouncedlike thea in theespeciallyatEnglishcolloquialword "pa," or "father."Sometimes,theendof a word,it is alsorepresentedasi'Tl or Nl (ban, ba ).Thesamesvmbolalsomarksa short/o/: seebelow.:emarksthe short/e/ sound,conventionallypronouncedlike theein theEnglishname"Ed," or in theword"less."Introductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymondl0

-1e, e-lr-lmarksthe short/i/ sound,conventionallypronouncedlike the I in"pit."l'-wo- vl - rmarksthe long/o/ vowel,conventionallypronouncedlike theoaof "coat,"or like theo of "rote."It is sometimesalsowritten:withoutthewawcomplement:I o.marksthe short/u/ vowel,conventionallypronouncedlike theooof "cook."juI -'lpronouncedmarksthe long/ii sound,conventionallylike thee inthename"Pete,"or like the i in theword thatthe i-vowelis long.marksthe short/o/ vowel,conventionallypronouncedlike theawof theword "paw." Notethatthisvowel is very closeto the a. Whenthesevowelsymbolswereinventedandappliedto the consonantaltext,theremightnot havebeena distinctionbetweentheo andasounds.All the same,it is conventionalto distinguishtwo ere , representsa andwhereit representso is not easy.I havetriedto disambiguatebefweenthetwo vowelsin transliteration.-t J Oi'rmarks a shortor long /e/ sound.In either case,the vowel isconventionallypronouncedlike the ay in say, or like the ey in convey.as'l eY,EY;Nl e', e', andiJJ eh,eh.Sometimesit is alsorepresentedDistinguishingbetweenthe shortand long e is often difficult. For thebeginningstudent,it will be helpful to transliteratethis symbolwith euniversallyand subsequentlyto learnthoseplaceswherethe symbolrepresentse.-wumarksthe long/u/ vowel,conventionallypronouncedlike theooof "noon,"or the u of "fune."Thisis the shewasymbolandmarksa mufinuredvowel,pronouncedconventionallylike thea in "above."Theshewasymbolalsomarksthe absenceof a vowel.Determiningwhich of thesetwoalternativesthe shewarepresentswill sometimesprovedifficult.Introductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymond11

FrNdNdThesethreesymbolsrepresentlike theultra-shortvowels,essentiallymunnuredvowelin nature,but eachhavinga slightlydistinctquality.(i.e.,N, lJ, tsandl'l; sometimesalsobeforeor after) andp andsometimesbefore),), andl). Unliketheshewa,whichonly srepresentthepresenceof apronouncedvowel.irt:-ayOccasionally,onefindsa commonin BiblicalAramaicis the short/a/ yodh,whichis pronouncedlike theEnglishword "eye."Notethatinthis casethe shewasymbolmarksthe absenceof a vowel.-lNotethatwhena kaphappearslastin a word it hasthis form: , it is conventionalto write this with a shewasymbol(l), thoughthis shewasymboldoesnotrepresenta vowelsound.Also importantto understandinghow Armaicwordswerepronounced,isunderstandingwherethe stressfalls.Usually,it falls on the lastsyllableof a word.Occasionallyit falls on the next-to-lastsyllable,in which casethe stressedsyllable:lll-lfis indicatedby an accentmark(. ):Exercise2a.Now, try transliteratingthe r you.Determiningwhich lettersaretrueconsonantsthewordsnot translatedandwhich arematre,s-consonantswill becomemuchclearerasyou beginto understandthe formsof nounsandverbs.-j?b --' melek("king")-'la: ("silver")(Becausethe shewais the first vowelof theword,it ispronounced.)Ftr-tll-ttFtlrrJIrIntroductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. ReymondI2

-FJ I - I:J1-j\ - rJ:n)ul:. )tJitn 'i'!'i?nj'f )Dn;il! :l! ):: 'i'E')u1l't;]7 l;'T'nn 1?n]Ii":: --:-''l7t;]'ln:l:T'Part2As mentioneda murmuredabove,distinguishingbetweenthe shewathatrepresentsrathervowel,andthe shewathatrepresentsthe absenceof a vowel is sometimesdifficult.In general,whena shortvowel(lal ,lel . ,lil ., lol , , lul .) comesbeforea shewa,the shewarepresentsthe absenceof a vowel;whena longvowel'(/il , , l1l , hl . ,loll ,lil 1) comesbeforea shewa,theshewarepresentsamunnuredvowel.For example,because denotesa shortvowel,the shewafollowingit in N!?D (",tl. king") representstheabsenceof a vowel.Similarlywith the shortlil in lt.-l:l ("he writes").On the otherhand,in lIJ"li;1 ("he let youknow")thei representsa longvowelandthusthe shewafollowingit ispronounced.(Thereareexceptions,for mostbut this holdstrue,by-andJargewords.)Exercise2b.from thosethatrepresentDistinguishthe shewasthatrepresentmurmured-vowelsthe absenceof vowelsby transliteratingthesewords.N?Ol ("the silver"):l ]'f n ("he let you know" or "he causedyou to know")lf n! ! ("you" for masculinepluralentities)j'-lnS ("thosewho aresaying")(The , symbolrepresentsd here.)'i]l!("building")n]l? ("The onewho is building")(The , symbolrepresentsa here,asdoesil,.)Introductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymond13

Remember:Theultra-shortvowels( A,!f d, S d) arealwayspronounced.Exercise2c.in thebiblicalbookof Ena (a:11).Thisis thebeginningof a letter,embeddedit:Transcribe'ni)! rn?u "T Nf-t.i*jltD-lg;T:"7)!i1?iTl-11!tD;s:T'Ju N?D*nluurnr i-l '-'t N"ll;t] ":t R?)* N'lil) !'-1] nlJj:l"This (is) a copyof the letterthattheysentto him:'To: Artaxerxes,thepeopleof Avar-Naharah.theking -- (From:)your servants,who . . ."'Now, let it be knownto theking thatthe Jews/JudaeansPart3: SyllabificationandVowelsA syllableneverbeginswith a vowel.ThereEachsyllablebeginswith a consonant.* a vowel(calledaretwo kindsof syllables,thosethathaveonly a consonant* a vowel a"open"syllables)andthosesyllablesthathavea consonant(called"closed"syllables).consonantIn theword:j{l'f n (h6*-de-'ak)("he let you know") the first syllableis"open"becauseit beginswith a consonant,but doesnot haveaconsideredat its end,ratherit endswith the longd vowel.Thesecondsyllableisconsonantitalsoan opensyllable.However,the lastsyllableis a closedsyllablebecausebeginsandendswith a consonant.o]) typicallyoccurin onlyShortvowels( , ., ., ., and, [whenit representstwo placeswithin a word:1) In a closedsyllable,syllable(eitherthelastsyllableof a word or in a syllablear 2) in an accented'with an accentmark( ): lfi!)i , ' ' 1 , a n d , [ w h e ni t r e p r e s e nat]s)m o s to f t e no c c u irnL o n gv o w e l s( ' . . , ' ,opensyllables,but canalsooccurin closedsyllables,no matterthepositionof thethevowelpatternsin Aramaicfrom thosestress.(This,incidentally,distinguishesin BiblicalHebrew,wherelongvowelsappearonly in opensyllablesor in stressedIntroductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. ReymondI4

closedsyllables;i.e.,in Hebrew,longvowelsdo NOT occurin closed,unstressedsyllables,but theyDO in Aramaic.)Givena form like :l{'1li'.T,it is impossiblefor a beginningstudentto know whetherasaor not the first syllableis closedor open,whetherit shouldbe pronouncedthree-syllableword /hd-de-'ak/or asa two syllableword l*hod-'-ak/.Thecorrectpronunciationis, in fact,difficult to know with certainty.It is easiestif beginningstudentssimplyassumethatall longvowelsarein opensyllables,unlessotherwiseresultsin thetransliterationho*de'ak.indicated.This assumption'ilt'i!13,Thewordsabove,tt?B ,N?:,and'i]!1,eachbeginwith a closedsyllable.Eachof theseclosedsyllablescontainsa shortvowel.Thewords:JfTli1, T"''lF ,andN')l beginwith anopensyllable.Eachof theseopensyllablescontainsa longvowel.Thismeansthatthe followingshewain eachwordrepresentsa murmuredvowel.mrr-ltqiAnothercharacteristicof Aramaicsyllabificationis thatwhentwo shewasoccursuchasin theword jlln:lside-by-side,theabsenceof a, thefirst representsvowelwhilethe secondrepresentsa murmuredvowel.RememberthatmanyAramaicwordshavea shewain theirfirst syllable.In almostin the first syllableof a wordrepresentseverycase,the shewathatappearsamurmuredvowelandshouldbe pronounced.Exercise2d.Transliteratethe following passagebasedonEzra (5:4):'il'tlrr:F NFi:lin)"l illl nirFujrftrjDT:l?N:':l ;111Then,thus,theyaskedthem:"What arethenamesof themenwho arebuildingthis building(lit., who thisbuildingarebuilding)."Introductorv Lessonsin Aramaic bv Eric D. Revmondt5

2e.ExerciseTranscribethe following(from Ena 5.5) into Aramaicscript:yehu*dayc'wo'eYn'dldhdhdnhdwdt'al SdbEvwela'baltilu* himm6*"The eyeof their Godwasoverthe eldersof the Judaeansandthey(i.e.,theelders)did not s:2 :"to" or "for"TD: "from"I-.)9 : "to" or "against"or "over" or "accordingto"Adverbs:N, : thisparticlenegatesverbstrllt : "also"Shortwords:: "then"]]llttit : "thereis"Nl;'l : "he"Nti.T: "she"'l : "and" "but"or!t'l] : "known"N]il? : "let it be" Qrlotethatthe first syllablecontainsa shortlel vowelin an opensyllable.This is the exceptionto therule pointedout above.Theultra-shortvowelbeneaththehehis secondarv:the olderform of thewordwouldhavebeenllehwe't.lIntroductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymondl6

Lesson3: Further Nicetiesof the Writins Svstem.PronounsPart1.A furtherdistinctionis madein the conventionalpronunciationof the consonants,forms:suchthat thebeth,gimmel,daleth,kaph,peh, andtawhavetwo pronouncedlike b (l), or asv (l)Thus,bethis pronounceda hardanda softpronunciation.is markedby a dot in the middleof theAramaicThis distinctionin pronunciationletter,or a line beneaththeRomanletter: blike v)b (pronouncedto"lg (conventionally,no distinctionis madein pronunciation)'':T'ldliketheth in"that,"or nodistinctionis made)d (pronouncedtt;)K:k (pronouncedlike the ch in"Chutzpah," identicalto I-l)5p5p (pronouncedlikeph in "phone")fltnlike the th in"thick" or "these")! (pronouncedIn otherwords,the letterwith the dot is pronouncedhard,while the letterwithoutis pronouncedis turnedsoft issoft.Thisprocessby whicha "hardpronunciation"calledspirantization.The "soft consonants"arereferredto asfricatives,spirants,orwhile the "hard consonants"canbe referredto as ts.lettersor bgdkptletters.Collectively,the consonantsarecalledbegadkephalWhetheror not a letteris pronouncedhardor softdepends,in part,on the placeofIn general,if a vowelprecedesthe letterwithin a word or within a sentence.abegadkephatletterit is soft,if a consonantprecedesit thenit is hard.For example,theword for sonis bar, or lJ. However,it mayalsobe pronouncedlvarl,or llIntroductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymond17

whenit is precededby a prefix,suchasa prepositionor in this casea conjunction:-1:l'l]:l ("and-a-son").like /tvar/ it is transliteratedbyAlthoughis pronouncedevena precedingword thatendsin a vowelcanconventionii*bar.Sometimesmakingit soft.consonant,affectthe nextword's begadkephalin the vocabularvlists.in the exercises.andwhenFor the sakeof consistencv.that standdiscussingindividual words, I haverenderedall begadkephatconsonantsfirst in a word asstops.Being cognizantof whethera begadkephatletteris pronouncedhardor soft isimportantbecauseit will often(butnot always)revealwhethera precedingshewarepresentstheabsenceof a vowelor a murmuredvowel.Thus,in the caseof ?Ol thehardpeh x:,ggeststhatthe shewaunderthesamekhrepresentstheabsenceof a vowel,whichalsomeansthatthewordbeginswith a closedsyllable.If the shewarepresenteda murmuredvowel,thenthatwouldresultin a softpehandthe absenceof a dot in thepeh, Anotherexampleis providedby Nf"lfN ; inthis case,the shewabeneaththereshmustrepresentthe absenceof a vowel sinceamunnuredvowelwouldresultin a softtaw. Consideralsothe masculinepluralabsoluteparticiplej'l l? ; the shewamustrepresenta murmuredvowel sincethebethis soft.Part2.A complicationto this systemof distinguishinghardfrom softhegadkephatis thatthe samemarkcanalsoindicatethata (N, lJ, n, JJ)andr (l), is doubled.Forexample,IFi!representsthisproblemwell. Thefirst dot,insidethekoph,indicatesthatthe"hard" (sinceit occursfirst in theword),while theis to be pronouncedconsonantseconddot,insidethe taw, indrcatesthatthe consonantis doubled(andthusalsopronounced"hard") We wouldtransliterate3FlJ askatteh.Notethetwo rules:l) Whenevera consonantappearstwice in a row, with no interveningvowel,it is alwayspronouncedhard.2) A murmuredvowelneveroccursbeforea doubledconsonant.IntroductoryLessonsin Aramaicby Eric D. Reymondl8

wingpassage- '-TNFlll\N?)FrDllll )y .':nDn2us]lu-19l'qq'. rq' t q'.F/JJJ1?:'\!)bI t { ; J t i stI:-'T NrT)I n'lrT-:'.'-lirfn.':'--:Part3.Thepronounsin Aramaichavethe followingforms:Sinzularlcs "f"2ms"you"2fs"vou"3ms"he";']iNffl tnl lcp "we"if;nl 2mp"you"El:lt !/ l''lfl) !2fp "you"]DlSll:1;1'l:l)N (E.:'lnn'J]bil)3mp"they"/ D.:3fs "she" tiJ3fp"they"I'lNPluralTheyareusedin manyrespectslike or the 2ndand3'dpersonswillalsobe foundin the verbforms.Exercise3b.Basedon what you know of Aramaic orthographyand syllabification,transliteratethe pronounsfrom the precedingchart:Singular1cs "I"Plurallcp "we"'ant2ms "you"(Bothshewasin thisformrepresenttheabsenceof a2mp"you"vowel.)2fs"you"2fp "you"3ms "he"3mp"they"3fs"she"3fp "they"Introductory Lessonsin Arqmaic by Eric D. Reymondt9

Part4.Syntaxof NominalExpressionsIn manylanguages,includingAramaic,onedoesnot alwaysneedtheverb"to be"whencreatingsentencesof the sort:"The king is good."In casesof this sort(lp), sometimesAramaicsimplyjuxtaposesthenoun(N?)D) with theadjectivewith the adjective(a predicateadjective,to be precise)comingbeforethe noun.S?B:PThis sentencecanbe distinguishedfrom thephrase"the goodking" by thewordorderandthe stateof the adjective(absolute,thatis, withoutthelt , - ending).Inthephrase"the goodking" the adjectivealwaysfollowsthe nounandagreeswiththenounin its :-Sometimes,a sentencewill juxtaposetwo nouns,suchas in the sentence"I am theking," which if translatedword-for-word from Aramaic would be "I king." In thesecases,the word that functionsas the subjectof the clauseusually comesfirst. Theword that follows is consideredthe predicate(eventhough in Aramaic it is not averb).: I amtheking.N]?F ;'Ut tHere "the king" is technicallythe predicateof the phraseand comessecond.Sometimes,howeverthe predicatecan come first and the subjectsecondand thiscan lead to confusion.For example,one can imaginea sentenceof the type belowin which eithernoun could function as the subjector predicate.In thesecases,contextis the only guide as to which shouldbe consideredthe subjectand whichthe predicate.-T)F il:tt! : A lion is a king or A king is a lion.In caseswherethepredicateis a ppearssecond,precededby the subject.N! )b Eg ;1:N : I amwith thekine.Introductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymond20

Exercise3c.Translatethe followingsentencesinto Aramaic,utilizingthe vocabularythatfollowsthe exercise:1.He is theking.2.He is in thehouse.3. We arein thehouse.4. Theyarebeforetheking.5. Accordingly,all arethere.6. Beforetheywerethere,we werebeforetheking.Vocabulary:Prepositions.! (or l) : "in" or "by"! (or l) : "aS"or "like"trlP : before(referringto place)nElP ]n / nD-li?n : before(referringto time)Adverbs:]! , NFi! "thus"or "accordingly"ilFn : "there"Conjunction:t'l,t-''l: "and","or", "but". Thesingleconjunctioncanbe translatedin a numberI,of waysbasedon the contextof a passage.Sometimestheconjunctiondoesnot needto be translated.Its pronunciationvariesaccordingto a numberof variablesoutlinedbelow::l ;Whenit is followedby !/1, EE, andD it becomeswhenit is followedby a consonant*murmuredvowel,it alsoturnsto:l ;'whenit is followedbv thevodhlosesits shewaandthe letterstogetherarewritten.'i. ;whenit is followedby anultra-shortvowel,thecorrespondingfull:-N-NJ.:- -qql)vowelreplacesit (e.g., ']and ']Nouns:nll i : "letter"(Nqf-UN: "theletter")f.ntl : "house" n:l : "thehouse";twosyllablesbay-!a')m.[ntroductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymond2l

)! : "all" (kol) (alsospelledbl, kol;?n : "king"(N?D: "theking")m.T'iltDlP: "copy"m.N.B."the house,"Nf:], containsa vowel-consonantTheAramaicexpressionlike thecommoncombinationcalleda dipthong,in this case-ay- (pronouncedletterasif it wereword "eye");this dipthongaffectsthe followingbegadkephatof taw soft.simplya vowel,makingthepronunciationIntroductory Lessonsin Aramaic by Eric D. Reymond22

Lesson4: The Nounwith a threeconsonantroot. Due to the fact thatEachAramaicword is associatedisidentifiiingtheroot consonantsmostAramaicwordshaveonly d1)n hastheroot ?n. eeingabletoit (usually)allowsyou torecognizetheroot of a word is importantbecausethe basicsemanticfield of the word andallowsyou to predicthow theunderstandwill changewhensuffixesareaddedto it. Additionallyitword'spronunciationareallowsyou to look theword up in a to root.we will considerthe four mostbasictypesof roots:For ourpurposes-T,;'J,T,n, 13, ,),D,),(i.e.,N, l, l,1. strong- ).n,:, N) consonantasthefirst consonant.2. firstweak* havinga "weak"(''1,asthe secondconsonant.3. middleweak- havinga "weak" (.1,') consonantn,asthethird consonant.4. final weak- havinga "weak" (''1, N) consonant'alepftis relativelystablein themiddleof a root,andthat,similarly,Noticethatnunts stablein themiddleandat theendof a root.Identifoingstrongrootswill not be metimesandverbsderivedfrom theserootswill disappearTypically,theweakconsonantswhenwill haveslightlydifferentformsthanthoseof the strongroots.Therefore,we describetheverbs,we will needto describethe morphologyof theserootsseparately.Part1: SimplerNounsa

Hebrew, both classical and modern. The origins of this alphabet are interesting, though to describe these origins would take too much space here. Suffice it to say that the alphabet in its origin is Aramaic, and is often described as "Aramaic Block Script." For this reason, I will simply refer to the al