Transcription

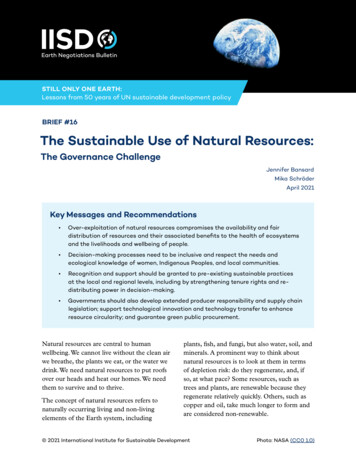

STILL ONLY ONE EARTH:Lessons from 50 years of UN sustainable development policyBRIEF #16The Sustainable Use of Natural Resources:The Governance ChallengeJennifer BansardMika SchröderApril 2021Key Messages and Recommendations Over-exploitation of natural resources compromises the availability and fairdistribution of resources and their associated benefits to the health of ecosystemsand the livelihoods and wellbeing of people. Decision-making processes need to be inclusive and respect the needs andecological knowledge of women, Indigenous Peoples, and local communities. Recognition and support should be granted to pre-existing sustainable practicesat the local and regional levels, including by strengthening tenure rights and redistributing power in decision-making. Governments should also develop extended producer responsibility and supply chainlegislation; support technological innovation and technology transfer to enhanceresource circularity; and guarantee green public procurement.Natural resources are central to humanwellbeing. We cannot live without the clean airwe breathe, the plants we eat, or the water wedrink. We need natural resources to put roofsover our heads and heat our homes. We needthem to survive and to thrive.The concept of natural resources refers tonaturally occurring living and non-livingelements of the Earth system, includingplants, fish, and fungi, but also water, soil, andminerals. A prominent way to think aboutnatural resources is to look at them in termsof depletion risk: do they regenerate, and, ifso, at what pace? Some resources, such astrees and plants, are renewable because theyregenerate relatively quickly. Others, such ascopper and oil, take much longer to form andare considered non-renewable. 2021 International Institute for Sustainable DevelopmentPhoto: NASA (CC0 1.0)

The Sustainable Use of Natural Resources: The Governance ChallengeTogether, natural resources make up a denseweb of interdependence, forming ecosystemsthat also include humans. As such, thedistribution of resources shapes the face ofour planet and the local distinctiveness of ourenvironments. People have formed differenttypes of cultural, spiritual, and subsistencebased relationships with the naturalenvironment, adopting value-systems that gobeyond economic framings.The use of natural resources has long beenconsidered an element of both human rightsand economic development, leading theUnited Nations, amid its work on advancingdecolonization in the 1960s, to declarethat “[t]he right of peoples and nations topermanent sovereignty over their naturalwealth and resources must be exercised inthe interest of their national developmentand of the well-being of the people of theState concerned” (UN General AssemblyResolution 1803 (XVII).Natural resources are often viewed as keyassets driving development and wealthcreation. Over time and with progressiveindustrialization, resource use increased.In some cases, exploitation levels came toexceed resources’ natural regeneration rates.Such overexploitation ultimately threatensthe livelihoods and wellbeing of people whoThis risk of resource depletion, such as deforestation inthe Brazilian Amazon, demonstrates the need to regulatenatural resource use to better preserve resources and theirecosystems. (Photo: iStock)depend on these resources, and jeopardizes thehealth of ecosystems.This risk of resource depletion, notablymanifesting in the form of fishery collapses,demonstrates the need to regulate naturalresource use to better preserve resources andtheir ecosystems. The very first UN conferenceon environmental issues, the 1972 UNConference on the Human Environment heldin Stockholm, Sweden, adopted fundamentalprinciples in this regard.“Nature makes human developmentpossible but our relentless demand forthe earth’s resources is acceleratingextinction rates and devastating theworld’s ecosystems.”The Stockholm Declaration not onlyaddressed resource depletion, but also benefitsharing: the objective to ensure that naturalresource use not only benefits the few, but themany, both within and across countries. It alsospeaks to the principle of inter-generationalequity: ensuring that today’s resource use doesnot compromise the availability of naturalresources for future generations.JOYCE MSUYA, DEPUTY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR,UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMMEIn fact, natural resource use relates to allthree dimensions of sustainability: socialbit.ly/still-only-one-earth2

The Sustainable Use of Natural Resources: The Governance ChallengeStockholm DeclarationPrinciple 2: “The natural resources of the earth, including the air, water, land, flora and faunaand especially representative samples of natural ecosystems, must be safeguarded forthe benefit of present and future generations through careful planning or management, asappropriate.”Principle 3: “The capacity of the earth to produce vital renewable resources must bemaintained and, wherever practicable, restored or improved.”Principle 5: “The non-renewable resources of the earth must be employed in such a way asto guard against the danger of their future exhaustion and to ensure that benefits fromsuch employment are shared by all mankind.”justice, environmental health, and economicdevelopment. The sustainable use of naturalresources strives for balance between thesedimensions: maintaining the long-term use ofresources while maximizing social benefits andminimizing environmental impacts.Natural Resource Use HasMore than Tripled since 1970Although the 1972 Stockholm Declaration laidout the fundamental principles for sustainableresource governance, the state of play half acentury later is sobering. The InternationalResource Panel (IRP), launched by the UnitedNations Environment Programme (UNEP),found that the global average of materialdemand per capita grew from 7.4 tons in 1970to 12.2 tons in 2017, with significant adverseimpacts on the environment, notably increasedgreenhouse gas emissions.The IRP also showed that “the use ofnatural resources and the related benefitsand environmental impacts are unevenlydistributed across countries and regions”(IRP, 2019, p. 27). For one, the per capitamaterial footprint in high-income countriesis thirteen times more than in low-incomecountries: 27 tons and 2 tons per capita,respectively. As WWF notes, “If everyonelived like an average resident of the USA, atotal of four Earths would be required toregenerate humanity’s annual demand onnature.” What’s more, since they generallyrely on resource extraction in other countries,high income countries outsource part of theenvironmental and social impacts of theirconsumption. At the same time, the IRP hasreported that “the value created throughthese traded materials in the countriesof origin is relatively low” (IRP, 2019, p.65). This imbalance highlights the globaldiscrepancies in the distribution of benefitsand negative impacts stemming from resourceuse, with countries “rich” in valuableresources not always benefitting from their“Human actions threaten morespecies with global extinction nowthan ever before.”INTERGOVERNMENTAL SCIENCE-POLICYPLATFORM ON BIODIVERSITY AND ECOSYSTEMSERVICES 2019 GLOBAL ASSESSMENT REPORTON BIODIVERSITY AND ECOSYSTEM SERVICESbit.ly/still-only-one-earth3

The Sustainable Use of Natural Resources: The Governance Challengeextraction, distribution, and use, yet sufferingthe most environmental harm.Fostering SustainableResource GovernanceA vast array of norms, institutions, and actorsinfluence decisions on natural resources,which is why we speak of natural resourcegovernance. A plethora of national legislation,intergovernmental agreements, regionalorganizations, certification mechanisms,corporate codes of conduct, and multistakeholder partnerships create a complex webof rules affecting how natural resources areused and benefits thereof are distributed.Since Stockholm, numerous multilateralagreements have developed a range ofoperational guidelines, targets, and standards.Some intergovernmental frameworks, such asthe Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)are broad in focus, while others are resourcespecific (Minamata Convention on Mercury)or relate to a specific geographical area(Convention on the Conservation of AntarcticMarine Living Resources). Industry initiativesand multi-stakeholder partnerships often focuson specific resources or sectors. Examples ofsuch initiatives include the Forest StewardshipCouncil, the Roundtable on Sustainable PalmOil, the Extractive Industries TransparencyInitiative, and the Better Cotton Initiative.Citizens also have agency over natural resourceuse: through the representatives we elect togovernment, our activist engagement, andour consumption and transport choices. Forinstance, carefully considering food productioncycles—what we eat, where and how it isgrown, and how it arrives on our plate—can go towards addressing the impact thatagricultural expansion has on forests, wetlands,and grassland ecosystems (FAO, 2018; IPBES,2019). However, this needs to be coupled withsystemic change across governance structures.These mechanisms and institutions are notalways complementary; in fact, at times theystand in conflict with one another. Consider,for instance, an energy corporation invokingthe Energy Charter Treaty to file arbitrationclaims against a country’s decision to phaseout coal—a decision taken in accordance withits obligations under the Paris Agreement onClimate Change.Balancing Rights andInterests over NaturalResourcesDetermining how people can—and should—access, benefit from, participate in decisionmaking on, and have responsibility overnatural resources has been shaped by conceptssuch as property and rights.On the one hand, property rights divide landsand territories into: private property, whererights are held by individuals or companies;common property, where rights are shared bya community; public property, where rightsare held by government; and open accessareas, where no specific rights are assigned(Aggrawal & Elbow, 2006). Property rightsare closely tied to rights over natural resources,which include the right to use a resource,such as hunting in a forest; or managementrights that grant authority to decide onuse, for example imposing seasonal huntingrestrictions. In terms of governance, differenttypes of ownership and access rights canbe held simultaneously by several actors: awetland can be owned by the state, managedby a local council, and used as fishing groundsby communities.bit.ly/still-only-one-earth4

The Sustainable Use of Natural Resources: The Governance ChallengeBiomass Fossil fuels Metals MineralsGlobal Materials UseKey FactsStatusProjectionsFrom 1970 to 2017, the annualglobal extraction of materialstripled, per capita materialdemand also grew.Environmental ImpactsFollowing the current trend,global materials use couldmore than double by 2060IRP research shows that, in 2017natural resource extraction andprocessing accounts for:(IRP, 2019; OECD, 2019). 90%of global biodiversity loss!27bil 90%19092billiontonnesbilliontonnesof water stress 50%7 tonnes/per capitaof global greenhouse gas(GHG) emissions.12 tonnes/per capitaWith the current trend,annual waste generationis projected to increaseby 70% by 2050Circular economyToday, the global economy is only 8.6%circular — just two years ago it was 9.1%(Circularity Gap Report 2020).Economytotal202020202050(World Bank, 2018).Solutions: Decoupling, Resource Efficiency, and Circular EconomyDecoupling natural resourceuse and environmental impactsfrom economic activity andhuman well-being is essential toaid the transition to asustainable future.Research from UNEP’s IRPindicates that investments inresource efficiency represent oneof the least-costly approaches tohelp meeting the SustainableDevelopment Goals and theParis Climate Agreement.By 2060, resource efficiency and sustainable consumption and productionmeasures could globally:Reduce 25%resource useReduce 90%GHG emissionsIncrease 8%economic activity(IRP, 2020)By 2050, adopting circular economy methods for 4 key industrial materials(cement, steel, plastic and aluminium) could globally:Reduce 40% GHG emissions. If include food systems, a total of 49%GHG emissions can be reduced.ResourceEfficiency Vector: Mecrovector & FreepikOverall such reductions could bring emissionsfrom these areas 45% closer to their net-zeroemission targets (Ellen MacArthur, 2019).Net-zeroemissionSource: UNEP and IRP (2020). Sustainable Trade in Resources: Global Material Flows, Circularity and Trade.Available at https://www.resourcepanel.org/reportsSource: UNEP and IRP (2020). Sustainable Trade in Resources: Global Material Flows, Circularity andTrade. United Nations Environment Programme.bit.ly/still-only-one-earth5

The Sustainable Use of Natural Resources: The Governance ChallengeThe notion of tenure security indicates that anindividual’s rights over natural resources andspecific lands are recognized and enforceable.These rights are key to avoiding conflict andfostering social security as well as long-termsustainable resource use.On the other hand, there are individual andcollective rights regarding quality of life. TheUnited Nations Declaration on the Rights ofPeasants and Other People Working in RuralAreas (UNDROP), for example, stipulatesthat “[p]easants and other people working inrural areas have the right to have access toand to use in a sustainable manner the naturalresources present in their communities that arerequired to enjoy adequate living conditions”and that they “have the right to participate inthe management of these resources” (Article5). UNDROP highlights the importance ofsmall-scale sustainable practices, and the needto strengthen the protection and recognitionof groups who have experienced historicalmarginalization and violent conflict overresource use.Similarly, the UN Declaration on the Rightsof Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) andInternational Labour Organization (ILO)Convention 169 (ILO 169) protect theindividual and collective rights of IndigenousPeoples. UNDRIP Article 8(2b) stipulatesthat states shall prevent and provide redressfor “any action which has the aim or effect ofdispossessing them of their lands, territoriesor resources.” Both texts also speak to theimportance of ensuring the free, prior, andinformed consent (FPIC) of IndigenousPeoples in relation to the use of theirlands, with UNDRIP Articles 11(2) and 28underscoring Indigenous Peoples’ right toredress for past FPIC infringements.There is also the right to a healthyenvironment, enshrined in regional treaties,including procedural rights on access toinformation and decision-making processes,as well as the right to clean air, a safe climate,healthy food, safe water, a safe environmentfor work and play, and healthy ecosystems(UN Human Rights Council, 2019).Ultimately, the effectiveness of these advancesin international law depends upon nationalgovernments’ readiness to implement them. Todate, only 23 countries have ratified ILO 169,and many countries around the world have yetto adopt appropriate legislation to protect therights enshrined in UNDRIP. To do so, andto protect associated rights under UNDROPand the right to a healthy environment,governments must adopt robust reformsacross national policies, laws, programmes,and institutions that prompt shifts in countrypriorities and ensure the mainstreaming ofenvironmental and social concerns acrosssectors, focusing especially on empoweringmarginalized groups. To ensure that decisionsacross society better address ecological andsocial wellbeing, prominent actors, includingthe UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rightsand the Environment, are calling for humanrights-based approaches to natural resourcegovernance.Overall, this constitutes a complexarchitecture, one that is dynamic in nature,often builds on customary practices, andrequires balancing “competing” rights andinterests through law and policy. Structuresare seldom straightforward: there are oftenoverlapping or even conflicting systems inplace, and this influences the sustainability ofresource governance.States play a central role in balancingrights and interests. Regulations addressingbit.ly/still-only-one-earth6

The Sustainable Use of Natural Resources: The Governance Challengethe extractive sector determine how acorporation’s exclusive user rights may impactthe general population’s right to a safe andhealthy environment. Approaches to thisbalancing act, and the distribution, recognition,and safeguarding of rights, and theimplementation of associated responsibilities,vary across states and change over time.At times, this balance of interests favors morepowerful actors. Stemming from historicallegacies and trajectories in decision-making,structural inequalities exist across resourceaccess, ownership, and tenure security (Oxfam,2014). These issues disproportionately impactwomen, rural communities, and IndigenousPeoples, who are often cast as passiverecipients to policy change, as opposed torights holders and key actors in the sustainablemanagement of natural resources.Women have faced historical exclusion fromdecision-making processes related to landand resources (UN Women, 2020). Due toenduring patriarchal gender norms across theworld, they hold less control than men overthe lands and resources they traditionally useand rely on for their livelihoods and wellbeing.Based on an analysis of 180 countries, theOrganisation for Economic Co-operationand Development (OECD) found that outof the 164 countries that explicitly recognizewomen’s rights to own, use, and makedecisions regarding land on par with men, only52 countries guarantee these rights in bothlaw and practice (OECD, 2019). As such, itis important that states ensure that women’srights over natural resources are realized andprotected through appropriate mechanisms.Indigenous Peoples also struggle to havetheir rights recognized. For instance, inFinland, Sweden, and Canada, legal disputeshave arisen over the challenge of balancingIndigenous and cultural leaders, including Sadhguru JaggiVasudev, Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, and Baaba Maal,discussed a values-based approach to land stewardship atthe 14th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to theUN Convention to Combat Desertification in 2019. (Photo:Ángeles Estrada, IISD/ENB)between states’ sovereign right to govern andexploit natural resources, and IndigenousPeoples’ rights to self-determination overtraditional territories and customary resourceuse. Globally, conflicts have also emergedover specific policy approaches, such asconservation methods relying on models ofstrictly protected areas, or the expansion oflarge infrastructure, such as the installationof hydraulic dams, which contribute to thedisplacement of Indigenous and rural peoples.The expansion of international investmenttreaties further aggravates existingpower differentials. In fostering thecommercialization and privatization of landand resources, and by often prioritizinginvestors’ rights and interests over those heldby local peoples, they risk restricting publicinterest policies and undermine the public’saccess to remedial action (Cotula, 2015, 2016).bit.ly/still-only-one-earth7

The Sustainable Use of Natural Resources: The Governance ChallengeThe Need for InclusiveGovernanceActivists and practitioners working tosafeguard rights linked to natural resourcesand secure tenure have been lobbying forstrengthened empowerment and participationof local groups, arguing that this fosters moresustainable and equitable resource governance.Alliances between women, youth, IndigenousPeoples, and local community groups haveemerged, connecting local-to-global efforts,and bringing international attention toinjustices. This includes grassroots alliancessuch as La Vía Campesina, which has lobbiedto protect farmers’ and peasants’ rights sincethe 1990s and was instrumental in the creationand adoption of UNDROP.Inclusive decision making is key for sustainableresource governance. Just as gender normshave influenced structures for access and use,they have also shaped our behaviors and theknowledge we acquire, with women holdingunique agroecological expertise linked tocrop resilience and nutrition (UN Women,2018). So, unless decision-making processesare gender-responsive and inclusive, theyrisk overlooking women’s specific needs androles, and will fail to ensure the inclusion ofecological knowledge important for enablingsustainable practices.The same can be said for including IndigenousPeoples and local communities in resourcegovernance. The second edition of the CBD’sLocal Biodiversity Outlooks illustrates theirsignificant contributions to the safeguardingand sustainable use of natural resources andbiodiversity. Important benefits come withinclusive and community-led governancestructures and decision-making processes,which, in addition to protecting and enablingsustainable use of resources, can strengthencommunity support systems and localeconomies, as well as revitalize Indigenous andlocal knowledges and languages.The Need for TransformativeChangeDespite efforts since the 1970s, current trendsin natural resource use are unsustainable,with potentially devastating results. The2019 IPBES Global Assessment Reportunderscored that transformative changeis necessary to protect the resources uponwhich human life and wellbeing depends. TheReport also acknowledges that, by its verynature, transformative change is often opposedby those with interests vested in the statusquo. Civil society actors therefore underscorethe importance for governments to addressvested interests and foster inclusive decisionmaking, along with a re-balancing of prioritieswith regards to rights and interests in order toensure ecological integrity and social justice(Allan, et.al., 2019). The Local BiodiversityOutlooks mentioned earlier offer importantexamples of bottom-up approaches to resourcegovernance that can foster sustainability whilealso addressing historical inequalities.Bearing in mind global and local inequalitiesin the distribution of resource use and benefits,achieving transformative change requires boldgovernmental action, both domestically and ininternational fora. We need fundamental shiftsin production and consumptions patterns,careful attention to value and supply chains,and the fostering of circular resource useand circular economies. Resource circularitybreaks with the linear model of “extractuse-discard” towards a “waste-as-a-resource”model that fosters a reduced need for resourceextraction, as well as encourages increasedreuse, repair and recycling. These objectivesbit.ly/still-only-one-earth8

The Sustainable Use of Natural Resources: The Governance Challengeare already enshrined in the 2030 Agenda forSustainable Development, with governmentsaiming to achieve the sustainable managementand efficient use of natural resources by 2030.While implementation has been too slow(IPBES, 2019), there is increased attentionto fostering resource circularity, hand inhand with efforts to promote secure laborstandards and reduce environmental impactsof resource exploitation. Most notable in thisregard are legislative initiatives that increaseproducers’ responsibility for the impactsof their products throughout their lifecycle.Placing responsibility for post-use disposalon manufacturers significantly increases thematerial recovery rate and incentivizes lesswasteful product design (OECD, 2016).To better balance the three dimensions ofsustainable resources governance—socialjustice, environmental health, and economicdevelopment—we must rethink our economic,social, political, and technological systemsthat currently enable damaging productionpractices and wasteful resource consumption.Other ways of living are possible, from theways we structure our societies and economies,the relationships we form with each otherand with our ecosystems, to ensuring that thepriorities of our leaders align with the interestsof the many rather than the few. To realizethese shifts, governments should developextended producer responsibilities and supplychain legislation to enhance fairer distributionof benefits and harms stemming from resourceuse and promote the protection of humanrights in ways that ensure ecological wellbeingand social justice.Decision making must be inclusive andaccount for the needs, rights, and knowledgesof historically marginalized communities andgroups. Governance structures must recognizeWe must rethink our economic, social, political, andtechnological systems that enable wasteful resourceconsumption. (Photo: iStock)and support pre-existing sustainable practicesat local and regional levels, as well as nourishthe emergence of more sustainable patterns ofresource use and management. This will requirestrengthening tenure rights and re-distributingpower across all stages of decision-making.Works ConsultedAggarwal, S. & Elbow, K. (2016). The roleof property rights in natural resourcemanagement, good governance andempowerment of the rural poor. s/2016/09/USAID Land TenureProperty Rights and NRM Report.pdfAllan, J.I., Antonich, B., Bansard, J.S., Luomi,M., & Soubry, B. (2019). Summary of theChile/Madrid Climate Change Conference:2-15 December 2019. Earth NegotiationsBulletin, 12(775). ula, L. (2015). Land rights and investmenttreaties. IIED. rate/12578IIED.pdfbit.ly/still-only-one-earth9

The Sustainable Use of Natural Resources: The Governance ChallengeCotula, L. (2016). Rethinking investmenttreaties to advance human rights. IIEDBriefing. rate/17376IIED.pdfFood and Agriculture Organization of theUnited Nations. (2018). Sustainable foodsystems: Concept and framework. http://www.fao.org/3/ca2079en/CA2079EN.pdfForest Peoples Programme, InternationalIndigenous Forum on Biodiversity,Indigenous Women’s Biodiversity Network,Centres of Distinction on Indigenous andLocal Knowledge, & Secretariat of theConvention on Biological Diversity. (2020).Local biodiversity outlooks 2. pdfIntergovernmental Science-Policy Platformon Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.(2019). Global assessment report onbiodiversity and ecosystem services. al Resource Panel. (2019). Globalresources outlook 2019: Natural resourcesfor the future we want. UN EnvironmentProgramme. rces-outlookOrganisation for Economic Co-operation andDevelopment. (2016). Extended producerresponsibility: Updated guidance forefficient waste management. on for Economic Co-operation andDevelopment. (2019). Social institutionsand gender index 2019 global report:Transforming challenges into xfam. (2014). Even it up: Time to endextreme inequality. https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file -en.pdfUN Human Rights Council. (2019). Reportby the Special Rapporteur on the issue ofhuman rights obligations relating to theenjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy andsustainable environment. A/HRC/43/53.https://undocs.org/A/HRC/43/53UN Women (2018). Towards a genderresponsive implementation of theConvention on Biological Diversity. ation-of-theconvention-on-biological-diversityUN Women (2020). Realizing women’s rightsto land and other productive resources.2nd ed. ther-productive-resources-2nd-editionThe Still Only One Earth policy brief series is published with the support of the Swedish Ministry ofEnvironment, the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment, and Global Affairs Canada. The editor isPamela Chasek, Ph.D. The opinions expressed in this brief are those of the authors and do not necessarilyreflect the views of IISD or other donors.Norwegian Ministryof Foreign Affairs

Council, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, and the Better Cotton Initiative. Citizens also have agency over natural resource use: through the representatives we elect to government, our activist engagement, and ou